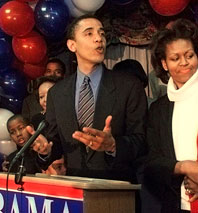

March 21, 2000.Photo: AP

Obama: Bungling his Congressional Race

When Obama announced his candidacy for Illinois’ First Congressional District in September of 1999, he made the decision to challenge four-term incumbent Representative Bobby Rush. Rush, a former Black Panther leader and Chicago alderman, had recently lost in his bid for mayor of Chicago, and Obama’s team sensed vulnerability. Soon after starting his campaign, Obama, with one term as a state senator under his belt, commissioned a poll and discovered his name recognition was at a paltry 11 percent, compared to Rush’s 90 percent. In the cold world of political calculation, Obama was put at further disadvantage when Rush’s son was gunned down by drug dealers, and sympathy flowed in the grieving father’s direction. Things only became worse when it was revealed that Obama missed an important gun-control vote in the state senate while he was on vacation with his family in Hawaii (an absence he attributed to his daughter becoming sick, preventing the Obamas from coming home). Knowing he would lose, Obama wrote in Audacity of Hope, he awoke each day “with a vague sense of dread.” In the end, the contest wasn’t even close: Obama lost by 31 percent. “It was a race in which everything that could go wrong did go wrong,” Obama wrote, “in which my own mistakes were compounded by tragedy and farce.”

McCain: The Keating Five Scandal

In 1989, McCain’s friend and campaign contributor Charles Keating became embroiled in a savings-and-loan scandal after making risky investments that led to 21,000 senior citizens losing their life savings. Keating approached five senators to intervene on his behalf, and the resulting congressional investigation into their actions became the biggest scandal of McCain’s career. McCain argued that he had only tried to ensure that his constituency was treated fairly, but he accepted $112,000 in campaign funds from Keating, he took numerous travel gifts, and his father-in-law made investments with Keating, implying that the banker had bought special favors. However, the Arizona senator also did the least to help Keating when regulators came calling. McCain attended two meetings, then, angry that Keating had called him a “wimp” for not doing more, cut off all ties with the banker while the other senators continued to lobby for him. The resulting investigation into the senators’ actions went on for two years; in the end McCain was reprimanded by the Senate Ethics Committee for using “poor judgment,” but was not found to have acted improperly. Despite this, McCain told aides during the investigation that the scrutiny and resulting negative publicity was “absolutely the worst thing that has ever happened to me.” In the aftermath of Keating Five, McCain has become a crusader in the fight against fund-raising abuses in politics, a move that Matt Welch, in McCain: Myth of a Maverick, likens to “an alcoholic using the federal government to lock up his own liquor cabinet.”