On a stormy evening in early September, a couple of hours before Barack Obama would present his new jobs plan to a joint session of Congress, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor was huddled in his Capitol office with a handful of aides, kicking around a question: Why does the president seem to hate him so much?

Various theories were floated. John Murray, Cantor’s deputy chief of staff, argued that it had something to do with his boss’s eloquence. “Eric articulates very strongly and aggressively a principled stance that’s conservative,” he said, “and they don’t like that.” Cantor himself chalked it up to basic political differences. “I think his view of the economy and how to fix it is so removed from reality,” he said, “and it’s just theory that may work in the classroom, but it does not work, according to my experience.”

Eventually, Brad Dayspring, Cantor’s communications director, weighed in. The president, Dayspring offered, “tends to personalize these policy disputes, it seems to me as an observer.”

Cantor turned to Dayspring and smiled. “I think, as an observer that you are, that’s probably a pretty astute observation.”

Of course, the most compelling explanation for the president’s animus toward the House majority leader is also the simplest: No one in Washington has done more to disrupt Obama’s first term—and threaten his chance at a second—than Cantor. The two men have clashed from the start. It was only three days after Obama’s inauguration that Cantor came to a White House meeting on the economic crisis and proceeded to hand out copies of the Republican plan to fix it—which Obama quickly dismissed. “Elections have consequences,” the president reportedly told Cantor, “and, Eric, I won.” A month later, at a White House fiscal-responsibility summit, Obama pledged to continue reaching out to Republicans because he was “a glutton for punishment” and then singled out the Virginia congressman for particular opprobrium: “I’m going to keep on talking to Eric Cantor. Some day, sooner or later, he’s going to say, ‘Boy, Obama had a good idea.’ ”

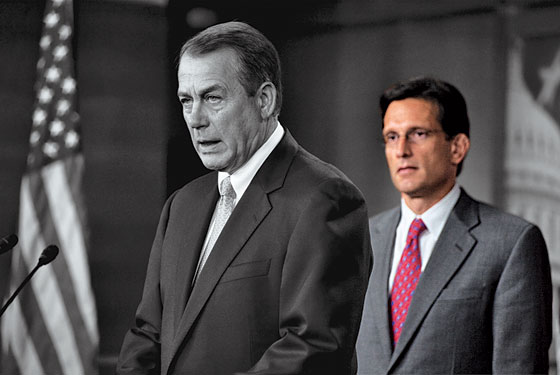

But Obama and other Democrats have never been as furious at Cantor as they were this past July during the debt-ceiling fight. For weeks, Obama had been negotiating with House Speaker John Boehner over a so-called “grand bargain” that would cut spending and raise taxes in exchange for a debt deal. But Cantor, who forcefully channeled tea-party Republicans’ opposition to any tax increase, had helped scuttle those talks. On a Wednesday afternoon, during a hiatus in the Obama-Boehner negotiations, a group of congressional leaders met for over two hours in the White House Cabinet Room, with Obama doing most of the arguing for the Democrats and Cantor for the Republicans. As the meeting was drawing to a close, Cantor and Obama repeated their arguments one final time—and then Obama erupted. “Eric, don’t call my bluff,” the president reportedly said. “I’m going to the American people with this.”

The episode might have been over, had Cantor then not gone in front of reporters in the Capitol and accused Obama of petulance. “It ended with the president abruptly walking out of the meeting,” Cantor said. “I was somewhat taken aback.” Democrats returned fire, with Harry Reid taking to the Senate floor to brand Cantor’s behavior as “childish.” In private conversations, they’re even more cutting. “Jerk,” “ungentlemanly,” “underhanded,” “patronizing,” and “smug son of a bitch” were just a few of the insults I heard when I mentioned Cantor’s name to Democratic lawmakers and aides. Bill Burton, the former White House spokesman who now runs a pro-Obama super PAC, says, “Cantor has had an outsized influence on how poisonously partisan Washington has been these last couple years.”

Cantor is 48 years old, but with his thick black hair and runner’s build, he looks considerably younger. And as he sat perched on a couch in his office that evening last month and reflected on his run-ins with Obama, he resembled no one so much as Eddie Haskell proclaiming his innocence. “I try to be deferential,” Cantor said in his buttery southern accent. “I mean, I’m a lawyer, I was raised in the sort of schooling, if you will, of deference to someone on the bench—and certainly to the president … I’m not this guy with horns and a partisan only.”

As if to prove it, he claimed he was ready to work with Obama on the jobs plan the president would unveil later that evening. The times demand it, he told me. But Cantor and his aides seemed to know that the bipartisan happy talk emanating from both sides was just that—and they were preparing, somewhat gleefully, for yet another clash and yet another round of very personal, very presidential attention. They noted that Michelle Obama would be sitting next to a high-school student from Cantor’s hometown of Richmond during the speech that night. (“I’m surprised they didn’t invite Eric’s opponent,” Murray quipped.) They speculated about the motives behind Paul Begala’s decision to conduct focus groups on Obama’s jobs speech in Cantor’s district. (“Then they can come out and say the people of Richmond support it,” Dayspring explained.) And they put the finishing touches on a jobs event Cantor would be doing the next afternoon in Richmond—which had been necessitated by the fact that Obama had picked the Virginia capital, of all places, as the site for the first rally of his jobs-bill push the next morning.

Soon it was time for Cantor to go to Obama’s speech. As the House majority leader, it is traditionally part of his job to escort the president into the House chamber, and he headed to the speaker’s ceremonial office. There, he met Obama, who, as Cantor later recalled, tried to make small talk about the two men’s children. Cantor wouldn’t have it. “Ohhh, I hear you’re coming to Richmond tomorrow,” Cantor said. Obama replied with a comment about the weather, but Cantor kept needling. “You know, Mr. President, I’m not going to be able to be there, since we have votes,” he mock-apologized. “But I’ll be there after you.”

Cantor’s role as Obama’s nemesis, as the National Review recently dubbed him, is remarkable for several reasons—none more so than the fact that, although he’s now the darling of the tea party, he initially rose to power in Washington by standing for almost everything the tea party is against. Elected to Congress in 2000, right as House Republicans were entering their Caligula phase, Cantor was soon tapped by Roy Blunt, the House majority whip at the time, to serve as his chief deputy. According to a former Republican congressman, Cantor was given a seat at the GOP leadership table on the advice of Blunt’s then-girlfriend, now-wife, who was a Philip Morris lobbyist and who appreciated the fact that Cantor is Jewish. “Abigail was Jewish, and she understood the implications for fund-raising,” the former congressman says. “Eric had access to donors we didn’t typically have access to.”

Cantor’s primary job as a member of the whip operation was to cajole his fellow Republican congressmen into voting for many of the bills the tea-partiers now decry as the height of fiscal irresponsibility —including, most infamously, the 2003 Medicare prescription-drug legislation, for which he worked hand in hand with pharmaceutical-industry lobbyists and Karl Rove. “There were some of us who certainly wanted him to play a more forceful role there in fighting against that legislation rather than for it,” recalls Jeff Flake, an Arizona congressman and Cantor ally who was one of 25 House Republicans to vote against the bill.

When Cantor wasn’t whipping votes, he was spearheading Tom DeLay’s defense against an ethics complaint—or, as Cantor called it at the time, “trumped-up charges” that were “an attack on the conservative movement.” “It’s the final phase that Democrats are coming to grips that Republicans are a permanent majority,” he told one reporter. He was also connected to the now disgraced Republican lobbyist Jack Abramoff. In 2003, Cantor—along with Blunt, DeLay, and House speaker Dennis Hastert—signed a letter to the Interior Department written at the behest of a Louisiana Indian tribe, an Abramoff client that was seeking to protect its gaming interests. That same year, Abramoff’s D.C. deli hosted a $500-a-plate fund-raiser for Cantor during which a tuna sandwich was named in honor of the Virginia congressman.

In early 2006, after Abramoff pleaded guilty to federal fraud and bribery charges, Cantor donated about $10,000 in political contributions he’d received from the lobbyist to a charity. This was par for the course for many congressmen at the time. But Cantor, unlike other House Republican leaders, went further. Although he never actually apologized for his past actions—“I wasn’t a senior member of leadership,” he says—he sensed that the tide was turning against House Republicans and that their permanent majority wasn’t so permanent after all. And so he began to reinvent himself as a reformer. The congressman who once defended DeLay was now one of the first House Republicans to call for an FBI investigation of Mark Foley. Having secured roughly $20 million in earmarks during his first three terms, he suddenly forswore them. And five days before the House GOP would lose its majority in the 2006 midterms, Cantor sat down with reporters and editors from Roll Call and called for his fellow Republicans to do some serious soul-searching: “Good Lord, you can’t just keep doing the things the way we’ve been doing them.”

When rank-and-file Republicans eventually came for the scalps of DeLay, Blunt, and Hastert, they left Cantor’s untouched. And he soon found new allies—namely California congressman Kevin McCarthy, who was elected to Congress in 2006, and Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan. They cast themselves as “a new generation of conservative leaders.” Ryan, a wonky backbencher on the budget committee, was “the thinker”; McCarthy, a gregarious backslapper, was “the strategist”; and Cantor was “the leader.” Together, they repeatedly lambasted the previous Republican majority for having lost its way and pledged to return the GOP to its small-government roots. By the time the Weekly Standard put the trio on its cover in October 2007 under the headline “Young Guns of the House GOP,” Cantor’s reinvention was complete. He was, as Fred Barnes’s accompanying article put it, “difficult to typecast as anything but a reform-minded conservative Republican.”

Having sufficiently cleansed himself of past sins, Cantor, with his finely tuned political radar, then picked up on—and, in turn, helped initiate—what has become the Republican Party’s most profound cultural shift: its belligerent intransigence. Cantor, as one prominent Republican told me, “is not a tea-party guy. He’s a business guy, a business Republican.” But he has managed to successfully elide this difference and, perhaps more than any other Republican in Congress, has politically positioned himself to take advantage of the GOP’s new obstructionist ethos. “Cantor comes from the more contemporary [Republican] school that says cooperation is a dirty word and compromise is an unpardonable sin,” says Obama adviser David Axelrod. “I think he’s a very ambitious guy who’s reading the direction of the Republican Party, and he’s trying to ride that wave.”

A few weeks after Obama won the White House, Cantor was elected House minority whip, the No. 2 seat at the Republican leadership table. The timing was not particularly auspicious. “It sucked,” Cantor says. “It was not a nice time to be around here. Faces were long, and people were upset.” With Obama’s approval rating up near the seventies, the question confronting Cantor and other Republican leaders was not whether the new president would be able to enact his ambitious stimulus package (given Democratic control of Congress, its passage was a foregone conclusion) but how many GOP votes he would get for it. Some in the GOP—including, according to several sources, Minority Leader John Boehner—were fearful almost to the point of resignation that they would lose a sizable number of House Republicans. That’s when Cantor made a decision that has set the tone for American politics ever since: He made it his mission to deny Obama any Republican votes for the stimulus.

The first thing he did was commission a national poll to show fellow Republican congressmen that while Obama was personally popular, his policies were not. Then he assembled what he called the House Republican Economic Recovery Working Group to come up with an alternative stimulus package. The group’s plan was larded with tax cuts that would make it a nonstarter for Obama, but the president’s expected rejection was part of the plan. “If we were going to oppose it,” Cantor says now of Obama’s stimulus package, “our members needed to be able to go home to their districts and say to the Rotary Club or their Chamber of Commerce that it’s not just ‘no’ but that we have our own way of doing it.”

Once Obama unveiled his own nearly $1 trillion stimulus package, Cantor went to work picking it apart piece by piece in the press. He realized—in a way that previous minority whips didn’t—that an essential part of his job was messaging. “The notion that a minority is going to be pushing pieces of legislation through the House is ludicrous,” explains John Murray. “So we needed to be communicating, and doing it very aggressively.” Working from a windowless office in the Capitol, three Cantor communication staffers ran a campaign-style war room that was devoted to finding the porkiest or most controversial pieces of Obama’s stimulus bill—from the $200 million to be spent in part on resodding the National Mall to the provision that devoted millions of dollars to family-planning initiatives—and then turning them into Drudge links and Fox News hits. Democrats ultimately wound up dropping a number of those provisions from the legislation, but it didn’t matter. When the bill passed the house eight days after Obama’s inauguration, it did so without a single House GOP vote.

That lockstep unity would carry over to future votes, including, most significantly, health-care reform. And while Obama chalked up some impressive legislative victories, he was unable to deliver on one of the fundamental promises of his presidential campaign: that he would change Washington and usher in a new era of bipartisanship. “I sat back after the stimulus vote and said, ‘We’ve really come together as a [Republican] conference,” recalls McCarthy, who was then Cantor’s chief deputy whip. “That’s when I knew we would win the majority. And I give Eric the majority of all the credit for making that happen.”

Since the 2010 election, of course, Cantor has had a much more lethal weapon at his disposal, one that he played a major role in creating: the 87 freshmen who make up more than a third of the Republican’s House majority. In the run-up to the midterms, Cantor, along with McCarthy and Ryan, used their “Young Guns” candidate-recruitment program to find Republicans who could capitalize on the growing tea-party backlash against Obama and Washington. “We wanted to bring ‘cause’ people to Congress,” says Ryan, “not people who were looking for political careers.”

The downside to recruiting non-career politicians is they don’t necessarily know how to run for office, so Cantor taught them the ropes. “He was always calling with advice,” says Cory Gardner, a freshman from Colorado. “I oftentimes wondered, now, surely he can’t call everybody because how much time does he have? But then I got to Congress, and I discovered that he was calling everybody.”

Even more important than advice was money. Cantor is one of the GOP’s most prolific fund-raisers—hoovering up dollars not only in Richmond, but in the Jewish precincts of Los Angeles and Miami as well as in New York, where hedge-funders and private-equity types appreciate his efforts to preserve the “carried interest” income-tax break. He is comfortable monetizing an extraordinarily wide swath of his life. “Michigan is fixing to be a big fund-raising deal for us,” Cantor’s political consultant Ray Allen Jr. told me when I met him at his office in Richmond. “His daughter is going to be a sophomore at Ann Arbor, and he’s up to see her there a lot.” Last election cycle, Cantor, through his PAC, donated $657,000 to the soon-to-be freshmen. He also helped raise $11 million for their campaigns, holding fund-raisers on their behalf, not only in Washington but also in their districts, 44 of which Cantor visited before Election Day. “You remember those guys that show up early,” says South Carolina freshman Tim Scott, “and Eric was one of the early guys that showed up.”

At a freshman-orientation meeting in the Capitol last December, Cantor used the occasion to give the group a pep talk. “We must ask ourselves,” Cantor instructed them, “ ‘Are my efforts addressing job creation and the economy? Are they reducing spending? Are they shrinking the size of the federal government while protecting and expanding liberty? If not, why am I doing it? … Why are we doing it?’ ” He called his reverie the “Cantor Rule” and subsequently had it printed up on laminated, red-white-and-blue-bunted index cards, which he distributed to members of the GOP caucus (and to at least one aide as a Christmas gift).

“I try to be deferential. Certainly to the president. I’m not this guy with horns.”

Over the past year, Cantor has continued to advocate on behalf of the freshman. He has pressured Boehner to share information that he was keeping close to his vest, including the status of his talks with the White House during budget negotiations in April. “We definitely wanted more information than we were getting,” says one freshman, “and a lot of us viewed Cantor as our advocate on that front.” In August, after Hurricane Irene ravaged the East Coast, Cantor went on Fox News to announce that additional funds for federal disaster relief would have to be offset by spending cuts. This was a position popular with tea-partiers, who are still angry that back in 2005 Congress tacked the cost of Hurricane Katrina’s cleanup onto the deficit. But it didn’t go over so well in Cantor’s own district, which not only had been hit hard by Irene but, a week earlier, had been at the epicenter of an earthquake, and Cantor was quickly forced to clarify that the money would be made available. When I interviewed Cantor for the first time one afternoon in late August in Richmond, it was four days after the hurricane and eight days after the earthquake—and he had just emerged from a series of meetings with nervous local leaders inquiring about disaster relief. Talking to me, he brought up the topic unbidden. “Of course I’m for prioritizing disaster relief,” he said. “We’ll find moneys.” When I later checked my Twitter feed, I noticed that during our one-hour interview, @EricCantor had tweeted the same point twice.

Still, although Cantor has occasionally found currying favor with the freshmen to have its short-term downsides, the strategy has paid significant dividends: In April, when the budget deal the House leadership team struck with Obama turned out not to have as many cuts as advertised, it was Boehner, not Cantor, who bore the brunt of the freshmen’s anger.

“I can text Cantor and get a response back in minutes,” says one freshman, explaining his allegiance. “I don’t know if Speaker Boehner even has a cell phone.”

And yet for all the loyalty many GOP congressmen feel toward Cantor, he is surprisingly unloved. Even his admirers say he lacks the social ease and natural confidence of most politicians. Ric Keller, a former Florida Republican congressman, recalls finding Cantor in the men’s room at the Greenbrier resort in 2003 moments before he was about to give a speech at the congressional GOP retreat: “There is Eric nervously pacing back and forth, and he says, ‘Ric, do you got any advice for me?’ And I was like, ‘Dude, you just got appointed chief deputy whip and made it onto the Ways and Means Committee. It’s Hanukkah every day for you!”

Cantor rarely socializes with his colleagues, and since he doesn’t golf or fish or have any hobbies, when he does find himself in social situations, he usually talks about work. “You’d get a lot of ‘Eric’s no fun,’ ” recalls a former House colleague who tried to include Cantor in group dinners; as it turned out, Cantor usually declined the invitations anyway.

Some veteran GOP lawmakers find Cantor’s coddling of the freshmen irritating. “I don’t know how—or why—Eric puts up with them,” one told me. And certainly there is no love lost between Cantor and Boehner. The golf-loving, wine-drinking, chain-smoking Boehner is said to consider Cantor to be a grind and a killjoy. Meanwhile, Cantor and especially his wife are known to have concerns over his secondhand-smoke exposure. “The most important person in the Republican caucus,” jokes one prominent Democrat, “is neither Boehner nor Cantor but the official food taster.”

As for those ideologically opposed to Cantor, they dislike him with an intensity that surpasses the usual partisanship—they accuse him of acting in bad faith. Some recall an episode from this past January, when, in a supposed gesture of bipartisanship, Cantor invited Nancy Pelosi to sit with him at the State of the Union. The problem was, he offered the invitation less than 24 hours before the speech, and through reporters. Pelosi had already arranged to sit with another Republican, and when she turned down Cantor’s invite, it led to headlines like “Pelosi Spurns Cantor on Seating.” Others remember how, after repeatedly rejecting Democratic congressman Steny Hoyer’s efforts to work on health-care-reform legislation, Cantor approached Hoyer for a meeting mere weeks before House Democrats were set to bring their bill to the floor—and then, after presenting Hoyer with a set of proposals like tort reform and “association health plans” that had long been anathema to Democrats, complained to reporters that Hoyer had rebuffed his efforts at bipartisanship. “It was unbelievable that he’d conduct himself in such a transparent way to set up a press story,” says one senior Democratic aide.

But Cantor has realized that, in Washington these days, being liked is not a substantial advantage. Much better to be deemed so unreasonable that your opponents ultimately feel no choice but to bend to your will. This was never truer than during the debt-ceiling fight. Although a number of the freshmen had said during the run-up to the 2010 elections that they would not vote to raise the nation’s debt limit, many House Republicans, who knew the calamity that would unfold if the nation did default, seemed to believe those were just empty campaign promises. “This is going to be probably the first really big adult moment” for the new GOP majority, Boehner told The New Yorkerthis past December. “You can underline ‘adult.’ And for people who’ve never been in politics it’s going to be one of those growing moments … [W]e’ll have to find a way to help educate members and help people understand the serious problem that would exist if we didn’t do it.”

Cantor was just as committed to avoiding default as the speaker (if for no other reason than his long-standing ties to Wall Street), but he also knew that the freshmen—and the GOP, by extension—would be more powerful if they avoided the Establishment grooming lessons Boehner appeared to be recommending. In early January, at a closed-door retreat for the GOP caucus in Baltimore, Cantor gave a speech trying to reframe the debt ceiling as “a leverage moment” over Obama. “I made the point that, look, this is an opportunity for us because we are in essence a blocking minority in Washington,” he told me. “We control half of one-third of government, and so we can for sure block bad things from happening legislatively. But it’s hard when you are in the majority in just the House to try and proffer and accomplish the kinds of things you want if the other side is not going to go along with it. And it’s hard to even start to compromise or find some points of agreement when you’re in this kind of supercharged political environment. So I looked at, What is really must-pass? What is it that’s going to have to see the House joining with the president and the Senate to get something done?”

Boehner eventually came around to Cantor’s way of thinking and, in a May speech to the Economic Club of New York, he spelled out exactly how the House Republicans intended to use their leverage: In exchange for voting to raise the debt ceiling, they’d require over $2 trillion in deficit reduction, all in the form of spending cuts and reforms. The previous month, Boehner tapped Cantor to represent House Republicans at bipartisan, bicameral deficit-reduction talks being led by Joe Biden. The move was widely viewed in Washington as an effort by the speaker to make sure that, unlike with the budget agreement of the previous month, his No. 2 had his fingerprints on any debt deal—and would catch some of the flak if the GOP caucus, especially the freshmen, ultimately turned against it.

But Cantor, by all accounts, embraced the assignment. Meeting two to three days a week for hours at a time, the Biden talks were a wonky affair, with the participants poring over spreadsheets. As they discussed the intricacies of entitlement reform and closing tax loopholes, Cantor revealed himself to be less ideological than anyone had expected. “I think everybody was really pleasantly surprised by Cantor’s approach to this and how constructive he was during the process,” says an administration official who worked on the talks.

But while he didn’t speak the borderline-fanatical language of the tea party, Cantor channeled their recalcitrance. Throughout the talks, he refused to consider any revenue increases. He painted his position as pragmatic. “The arrival of the 87 freshmen has tended to shape what we can and can’t deliver in terms of a majority,” Cantor explains. “You’d have Baucus and you’d have Geithner say to me, ‘What are you giving up? Y’all need to do revenues.’ And I kept responding, ‘You don’t get it. This is an existential question for a fiscal conservative. Raising the credit limit allows for more spending, all right? That’s the deal here, so it is a big deal for us to be voting for this.’ ”

Of course, Cantor’s supposed pragmatism afforded him a substantial ideological advantage. “You don’t get a free pass because of your Luddites,” Biden told Cantor at one point. But that’s exactly what Cantor was able to create for himself and the GOP, successfully transforming the intransigence of a rump faction into an insurmountable roadblock. “The question for Cantor was whether he wanted to take the lead on convincing elements of his caucus to make some compromises,” says one Democratic congressman. “But Cantor was less interested in leading than following.” In retrospect, it’s clear that Cantor wasn’t following—he was outwitting.

By late June, the Biden talks had identified around $2 trillion in cuts, but Cantor’s hard line on revenues was becoming a bigger sore spot in the discussions. At the end of an unusually acrimonious meeting on a Wednesday afternoon, Cantor approached Biden in the hallway to talk about whether the group had run its course. The vice-president said he thought that it had only one or two more sessions left. Besides, Biden told Cantor, now that Boehner and Obama were negotiating directly—and would be meeting that night, in fact—it didn’t make sense to keep the group going much longer. This, it turns out, was news to Cantor. Boehner had kept his direct talks with the president a secret. Cantor, blindsided, announced the next morning that he was dropping out of the talks.

Over the next few weeks, Boehner and Obama continued to negotiate their grand bargain—and the Boehner-Cantor relationship became more fraught. In early July, when the president and the speaker presented the outlines of their $4 trillion tentative deal to congressional leaders at a White House meeting, Cantor balked at the revenue increases, saying there was no way the GOP conference would vote for them. Two days later, The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial blasting the proposed “grand bargain”—the details of which, many on the Hill believe but Dayspring denies, were leaked to the Journal by Cantor—and Boehner was facing an open rebellion by the freshmen and other conservative members of his caucus. Later that day, Boehner told Obama that the deal was off.

It’s conventional wisdom in Washington that Cantor lusts after Boehner’s job and is constantly scheming for ways to take it. “The problem comes in when you have your No. 2 guy more interested in the political ramifications of all this,” one anonymous congressional Republican told Politico in July. “You don’t have to be very bright to figure out what in the hell [Cantor] is doing.” Cantor, naturally, disputes this. “Listen, everybody writes that I want to be speaker,” he told me during one of our conversations. “Well, that’s news to me.”

That’s almost certainly a lie. But it would be a mistake to assume that Cantor wants to be speaker at any cost—or even any time soon. Although he’s clearly ambitious, Cantor has also repeatedly displayed a cautious streak over the years. Several times during his congressional career, he’s been urged to mount a challenge against the person above him on the leadership ladder—first Roy Blunt, now Boehner. Each time he’s taken a pass, surely realizing that, in internal House politics, attempted coups usually end in murder-suicides. “Nine times out of ten, Cantor will choose to outwork somebody rather than knife him,” says one Republican congressman.

Cantor loyalists insist that his actions during the debt-ceiling negotiations were an attempt to help Boehner, not undermine him. “Eric was trying to save Boehner from himself,” says one congressman close to Cantor. Had Boehner agreed to a grand bargain with Obama, it would have sparked a revolt inside the GOP conference. As next in line—or “the conscience of the conference,” in the words of Colorado freshman Cory Gardner—Cantor would have been under tremendous pressure to challenge Boehner for the speakership. Some Cantor allies believe he could have won such a challenge. But the ill will that would have resulted from Boehner’s defenestration might have doomed a Cantor speakership from the outset. “Eric doesn’t want a Pyrrhic victory,” says one congressman close to Cantor. “He wants Boehner to have a successful speakership, which would maintain a Republican majority and give Eric the opportunity to become speaker down the road. And Eric is young enough to wait for that.”

Cantor’s waiting game has been made easier, for now, by the fact that he emerged from the debt-ceiling fight with the upper hand: The final deal reflected his hard line against tax increases, and Boehner is now in lockstep with that strategy. The speaker tapped Jeb Hensarling, a conservative Texas congressman and a Cantor ally, to serve as the GOP’s co-chair on the bipartisan super-committee whose deficit-reduction recommendations are due at the end of November. And two weeks ago Boehner declared that those reductions should come only in the form of spending cuts and entitlement reforms, not tax increases. “I don’t think that the differences we have with the president are going to be solved before the election,” Cantor told me. “And I don’t know if John Boehner really thinks that they can, either.”

When Obama’s jobs speech was over, Cantor headed to the Capitol’s Statuary Hall, which, following presidential addresses, morphs into a giant spin room. Dayspring had already e-mailed his boss some talking points: “Encouraged w/president’s renewed focus on jobs … Good people can disagree, but they don’t have to disagree on everything.” Now, as Cantor visited the stations of the cable-news cross, he tried to strike those conciliatory notes. “I heard a lot of things in the president’s speech tonight that I think both sides can agree on,” he told CNBC.

But away from the cameras, Cantor was far more disparaging. As he rode in an SUV to the Fox News studios, where he was scheduled to appear on The Sean Hannity Show, Cantor regaled his aides with the smack he’d talked to Obama.

“Seriously, did you bring up Richmond?” Dayspring asked.

“Oh, I did,” Cantor boasted.

As for the speech itself, Cantor complained, “How does it make it easier when he’s like, ‘This is my package, pass this bill! And if you don’t, I’m going to tell the people across the country.’ It’s almost like when he said ‘Call my bluff.’ He said, ‘I’m gonna take it to the American people.’ I’m like, Where’s the chip there?”

Sure enough, in the coming weeks, Cantor and other Republican leaders would back away from any hints of compromise as they sharpened their attacks on Obama’s jobs package. Obama, meanwhile, presented a deficit-reduction plan that offered the GOP far less than what he’d been prepared to give Boehner during the debt-ceiling negotiations. And in late September, it took multiple votes and desperate negotiations for Congress to pass a routine spending bill to keep the federal government from shutting down at the end of the month. For all the fierce urgency of now, it became painfully clear that Republicans and now even Democrats had retreated to their partisan trenches and that nothing would get done in Washington until after November of the next year—if even then.

Now sitting inside the Fox studio, a makeup artist dabbed at Cantor’s face. “You’re nice and tan here,” she told him.

“A couple weeks ago, I was in Israel,” Cantor replied, making small talk about a trip he led there of 56 Republican members during the August recess.

“A lot of them told me they went,” she cooed. “They said it was great.”

When his makeup was done, Cantor picked up his BlackBerry and began scrolling through his e-mails. “Look at this,” he said to Dayspring and handed him the device. “It’s from the DSCC”—the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee. Dayspring gazed into Cantor’s phone and let out a hearty laugh.

Then Cantor shared the joke with the rest of the studio. “It’s talking about the presidential candidates,” he explained. Reading from his phone, he continued: “ ‘And one of these tea-party panderers will be the nominee and will be one step away from the presidency. If he or she wins, and we lose the Senate, they’ll join up with Eric Cantor for total control of the government.’ ”

Cantor paused and then let out a short, high-pitched giggle.

“It’s so silly,” he said.