As usual, the Enquirer broke the story. And as usual, it was Representative Barney Frank—Vice-President Clinton’s closest confidant, and her favorite public escort in the years since her divorce—whom President Gore asked to break the news.

“Bill married her,” Frank told her softly, as they sat backstage at the Fort Dodge Municipal Building. “They sealed the deal in a suite at the Bellagio. Besides the Clark County justice of the peace, the only witnesses were Tiger and Clooney, but it wasn’t a stunt. What’s done is done.”

Vice-President Clinton stiffened in her makeup chair. In an hour, she was scheduled to tangle with Senator John Edwards in their last debate before the caucuses, but now she wasn’t sure she could go on. A plume of gastric acid rose in her throat, suffused with the taste of a thousand turkey sandwiches gobbled in diners from Des Moines to Bettendorf.

“What was the little slut wearing on her big day?”

Her question caught Frank up short. He knew, as few did, that Hillary’s famous sternness masked a wicked, absurdist sense of humor, but he wondered if there was something more in play here: actual jealousy, primitive, unfeigned. Who would have thought it? After all he’d done to her? And all that he was doing even now.

Mrs. Carla Bruni Clinton—it had to hurt. Resplendent in Dior.

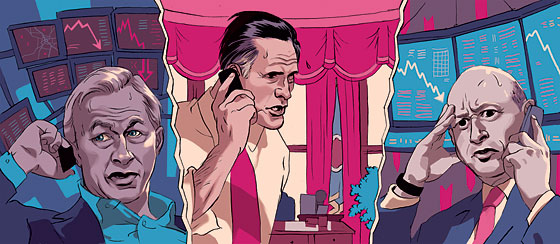

Sympathy didn’t win Hillary any votes, though it did get some applause from Oprah’s in-studio audience that night. And Senator Edwards played everything just right. He didn’t gloat about his functioning marriage but let it hover in the background, a symbol not of his moral superiority but of his immersion in the suburban mundane. He lost in Iowa, but only barely. And then the overheated financial markets crashed in February, owing to the unraveling of those weird, ill-understood investment vehicles, “insur-a-trades.” Citibank, Goldman Sachs, and AIG were left to sink or swim—and quickly sank, bringing with them a quarter of the nation’s banks. The public recoiled from the chaotic Clintons and their unruly, Euro-trashy lives, weary of melodrama in all its forms.

The election became a contest between two haircuts. Following the primaries, both Edwards and Romney shifted to the center, particularly on economic issues. Both bemoaned Wall Street’s corruption and incompetence and called for hearings and tightened regulation. (Never mind that Gore himself had fought against some of the banking deregulation that was going on. Big donors had put too many people into Congress, not to mention Gore himself, and the votes just weren’t there.) Both candidates sought to put “America back to work” by fighting “unfair foreign competition.” And both promoted universal health care, Romney on the Massachusetts model and Edwards on his own broader plan based on Canada’s. President Gore supported Edwards, of course, but with a marked lack of passion, as though he had some unstated reservation about the dazzlingly boyish candidate and his even more dazzling running mate, the former deputy attorney general and all-around man-of-the-future Barack Obama.

The young Illinois senator was new and squeaky-clean, having been appointed by Governor Rod Blagojevich to fill out Senator Jack Ryan’s term after the latter’s sex scandal. So Obama was given the dirty job of casting aspersions on Romney’s Mormonism. “Polygamitt,” as the Internet jokesters dubbed him, refused to respond directly to the jibes. After Romney’s running mate, former Vice-President Lieberman, compared anti-Mormonism to anti-Semitism in a speech to the Utah chapter of B’nai B’rith, the issue died out entirely.

Then, in October, three weeks before Election Day, disaster struck for Edwards. As usual, the Enquirer broke the story. Three days of media mayhem ensued concerning Senator Edwards’s fuzzily-photographed “love child,” and finally President Gore himself intervened to demand that Edwards step aside. An emergency poll of delegates conducted through a live-streamed “Teleconvention” chose Vice-President Rodham to replace him, but the damage to the Democrats was done. A 60 Minutes interview in which the former Mrs. Clinton was joined by her ex (his new trophy wife reportedly in hiding at a certain Hollywood actor’s Lake Como mansion) did nothing to reverse the tide. “It’s time America, starting with me, did right by this fine woman,” the former president tearfully declared, looking over at his ex-wife, then into the camera. “Please, I need your help.”

And what did President Gore say in defense of the harried, desperate Clintons, no longer a couple but once again a team? Not a single word.

After President Romney (electoral votes: 362) accomplished the impossible, pushing through, with bi-partisan support, a strikingly simple health-care bill for which even Fox News expressed grudging admiration, the nation seemed headed for a period of calm unseen since the Eisenhower years. Unemployment remained high at 9 percent, but business leaders agreed that the decision to let Goldman et al. crash and burn had set the economy up for a true rebound from an authentic structural bottom. In the meantime, the terrorist threat had finally assumed what most believed would be its ultimate form: a perennial limited danger on the order of building collapses or salmonella outbreaks.

Romney’s second great legislative coup—a comprehensive energy policy with a place for the new “micro-nuclear” plants that were about to come online in India—attracted no opposition from his predecessor, which many took as yet another sign that a long-awaited postpartisan era was at last at hand. In realms besides the strictly political —journalism, pop music, TV, and movies—pundits detected, and were quick to celebrate, a temperate, optimistic “new civility.” Media outlets that failed to heed the trend, such as the ever-quarrelsome Fox News, were rewarded with plunging ratings, while public figures identified with conflict, like Sean Hannity and Kanye West, drifted toward obscurity.

A prudent Romney, aware that most of his term still lay ahead of him, resisted taking credit for the new mood. At a festive Thanksgiving Day dinner in the White House whose dessert course was open to the press, he turned to the man beside him, raised his glass (filled with seltzer rather than Champagne), and toasted the man he now called “Uncle Al” for “smoothing and broadening the way.” Warm smiles were exchanged. The cameras drank them up.

The Tabernacle Choir broke out in song.