In the past few weeks, Sarah Palin has been variously described as a diva who engaged in paperwork-throwing tantrums, a shopaholic who spent $150,000 on clothing, a seductress who provocatively welcomed staffers while wearing only a towel, and a “whack-job”—contemporary code for hysteric. Worse, she was accused by a suspiciously gleeful Fox News reporter named Carl Cameron of not knowing Africa was a continent, of being unable to name the members of NAFTA, indeed of being unable to name the countries of North America at all. (“But she can be tutored,” Bill O’Reilly told Cameron, as though speaking of a small child.) More significant than the dubious origins of these leaks, or the fact that the campaign that cried “sexism” at every criticism of its vice-presidential nominee was engaging in its own misogynistic warfare, is the fact that all of the allegations were so believable. After all, Palin had earned herself a reputation as, in the words of one Fox News blogger, “something of a policy ditz.”

It’s hard to get too worked up on Palin’s behalf, of course; she was complicit in her crucifixion. But it is disappointing to watch what some have called the “year of the woman” come to such an embarrassing conclusion. This was an election cycle in which candidates pandered to female voters, newsweeklies tried to figure out “what women want,” and Hillary Clinton garnered 18 million votes toward winning the Democratic nomination. The assumption was that these “18 million cracks in the highest glass ceiling,” as Clinton put it, would advance the prospects of female achievement and gender equality. It hasn’t exactly worked out that way.

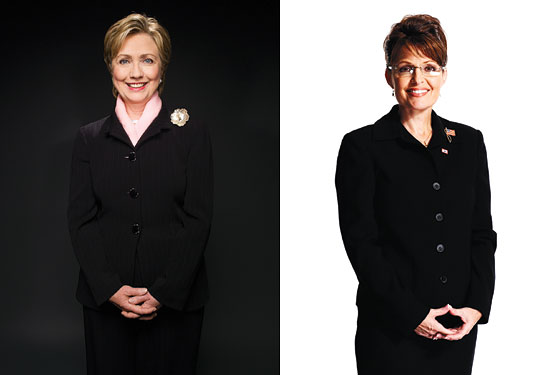

In the grand Passion play that was this election, both Clinton and Palin came to represent—and, at times, reinforce—two of the most pernicious stereotypes that are applied to women: the bitch and the ditz. Clinton took the first label, even though she tried valiantly, some would say misguidedly, to run a campaign that ignored gender until the very end. “Now, I’m not running because I’m a woman,” she would say. “I’m running because I think I’m the best-qualified and experienced person to hit the ground running.” She was highly competent, serious, diligent, prepared (sometimes overly so)—a woman who cloaked her femininity in hawkishness and pantsuits. But she had, to use an unfortunate term, likability issues, and she inspired in her detractors an upwelling of sexist animus: She was likened to Tracy Flick for her irritating entitlement, to Lady Macbeth for her boundless ambition. She was a grind, scold, harpy, shrew, priss, teacher’s pet, killjoy—you get the idea. She was repeatedly called a bitch (as in: “How do we beat the … ”) and a buster of balls. Tucker Carlson deemed her “castrating, overbearing, and scary” and said, memorably, “Every time I hear Hillary Clinton speak, I involuntarily cross my legs.”

Career women, especially those of a certain age, recognized themselves in Clinton and the reactions she provoked. “Maybe what bothers me most is that people say Hillary is a bitch,” said Tina Fey in her now-famous “Bitch Is the New Black” skit. “Let me say something about that: Yeah, she is. So am I … You know what? Bitches get stuff done.” At least being called a bitch implies power. As bad as Clinton’s treatment was, the McCain campaign’s cynical decision to put a woman—any woman—on the ticket was worse for the havoc it would wreak on gender politics. It was far more destructive, we would learn, for a woman to be labeled a fool.

When Sarah Palin first stepped onto the national stage, I was, like many women, intrigued by her. Here was a woman who—even if you didn’t agree with her politics—seemed to have achieved what so many of us were struggling for: an enviable balance between career and family. She was “a brisk, glam multitasker,” to quote the Observer’s Doree Shafrir, with a good-natured stay-at-home husband at her side and several adorable young children in tow. She was running a state and breast-feeding a newborn and yet, amazingly, did not seem exhausted. There was something inspiring about seeing a woman so at ease with her choices, even as both liberal and conservative critics chided her for running for vice-president when her family needed her. Politics aside, when, at the convention, she delivered a politically deft speech like a pro, it was pleasing to witness the first woman on a Republican ticket perform so well.

Of course, the myth of Sarah Palin unraveled almost as quickly as it was spun. By now, her bizarre filibustering, discomfiting blank stares, weird locutions, and general tendency to trip over herself verbally are familiar. First, there was the painful Charlie Gibson interview, in which Palin adopted a Toastmasters-style technique of repeating her interlocutor’s name in a vain attempt to sound authoritative. Then Katie Couric, with a newfound air of gravitas, smothered Palin with her simple questions and soothing manner: Palin appeared stunningly uninformed, lacking a basic fluency in foreign policy and economic theory. Even if she had frozen up out of nervousness, or fell into the category of smart-but-inarticulate, it was still unacceptable that she couldn’t recall Supreme Court decisions she disagreed with or name a single periodical she reads. Time? Newsweek? Hello?

Palin was recast as the charmer, the glider, the dim beauty queen, the kind of woman who floats along on a little luck and the favor of men. In a recent issue of The New Yorker, Jane Mayer recounted how a handful of conservative Washington thinkers became besotted with Palin during a trip to Alaska and subsequently began to promote her in Washington: The National Review’s Jay Nordlinger described the governor as “a former beauty-pageant contestant, and a real honey, too,” Bill Kristol called her “my heartthrob,” and Fred Barnes noted she was “exceptionally pretty.” While it’s obviously not Palin’s fault that men find her attractive, it is fair to criticize her for campaigning on a platform of charm rather than substance. In what Michelle Goldberg called a “brazen attempt to flirt [her] way into the good graces of the voting public,” she waved and winked and smiled—even during the debate—and called herself “just your average hockey mom.” (Never mind that it’s impossible to imagine a male candidate mentioning fatherhood as the source of his readiness to be the nation’s second-in-command.) Her running mate called her “a direct counterpoint to the liberal feminist agenda for America,” and her “Joe Six-Pack” fans seemed to appreciate her nonthreatening approach. To quote a former truck driver named Larry Hawkins who was interviewed by the Times at a Palin rally: “They bear us children, they risk their lives to give us birth, so maybe it’s time we let a woman lead us.”

It was enough to incense those of us who related to Hillary Clinton and her plight. “What’s infuriating, and perhaps rage-inducing, about Palin, is that she has always embodied that perfectly pleasing female archetype,” Jessica Grose wrote on Jezebel.com, in a post titled “Why Sarah Palin Incites Near-Violent Rage in Normally Reasonable Women.” Palin had taken a match and set fire to our meritocratic notions that hard work and accumulated experience would be rewarded. “As has been known to happen in less exalted workplaces,” Katha Pollitt wrote, “Palin got the promotion because the boss just liked her.” Her blithe ignorance extended from foreign policy to the symbolic value of her candidacy. By stepping into the spotlight unprepared, Palin reinforced some of the most damaging and sexist ideas of all: that women are undisciplined in their thinking; that we are distracted by domestic concerns or frivolous pursuits like shopping; that we are not smart enough, or not serious enough, for the important jobs.

In a rare moment of sympathy for Palin, Judith Warner, writing in the Times, noted that Palin’s admirers must “know she can’t possibly do it all—the kids, the special-needs baby, the big job, the big conversations with foreign leaders. And neither could they.” But many women do manage to do it all, or pretty close to all. They at least manage to come prepared for the big conversations and the critical meetings, no matter what they have going on at home. “Do we have to drag out a list of women who miraculously have found a way to balance many of these factors—Hillary Clinton? Nancy Pelosi? Michelle Bachelet?—and could still explain the Bush Doctrine without breaking out in hives?” wrote Rebecca Traister in Salon.com. Why then must Palin’s operatic failure be the example that leaves a lasting imprint?

And so, here we are, nearly two years after Hillary Clinton declared her candidacy. While it’s true that societal change comes in fits and starts and the Clinton campaign went a long way toward helping voters imagine a female commander-in-chief, I can’t help but think that our historic step forward was followed by more than a few in the opposite direction.

In August, after Clinton had dropped out of the race but before Palin was selected as the vice-presidential nominee, the Pew Research Center published a study on gender and leadership. A remarkable 69 percent of respondents believed that men and women made equally good leaders. In fact, women were rated equal to or better than men in seven of eight “leadership traits,” such as honesty, intelligence, ambition, creativity, compassion—the only quality on which men scored higher was decisiveness.

Two months later, when voters were asked to rate the leadership ability of one particular woman, the results were just as striking. According to exit polls, 60 percent of voters thought Palin was not qualified to be president if necessary. It’s true that Sarah Palin is only one woman, and we’ve seen male candidates of questionable readiness, like the oft-mentioned Dan Quayle, and even presidents of questionable intelligence, such as George W. Bush and Ronald Reagan, whom Clark Clifford once called “an amiable dunce.” But because so few women are present at the highest levels of government, they carry the burden of representing their gender more so than men. In politics as in business, an unqualified woman does more damage than no women at all. She serves to fortify the stereotypes that the next woman will have to surmount.

In the end, women can take pride in the fact that we helped break another set of retrograde stereotypes and prejudices with the election of Barack Obama. Harvard sociologist Orlando Patterson notes that “for the first time since enfranchisement, [women] voted in greater numbers, and more progressively, than men,” favoring Obama by a 13 percent margin, while men were almost evenly split. In doing so, we selected a candidate whose views on issues like health care and equal pay and reproductive rights align with our interests.

But among the darker revelations of this election is the fact that the vice-grip of female stereotypes remains suffocatingly tight. On the national political stage and in office buildings across the country, women regularly find themselves divided into dualities that are the modern equivalent of the Madonna-whore complex: the hard-ass or the lightweight, the battle-ax or the bubblehead, the serious, pursed-lipped shrew or the silly, ineffectual girl. It is exceedingly difficult to sidestep this trap. Michelle Obama began the campaign as a bold, outspoken woman with a career of her own, and she was called a hard-ass. Now, as she prepares to move into the White House, she appears poised to recede into a fifties-era role of “mom-in-chief.” It will be heartbreaking if, in an effort to avoid the kind of criticism that followed Hillary Clinton, the First Lady is reduced to a lightweight.

Many will say we’ve come a long way this year. The truth is we have a long way to go.