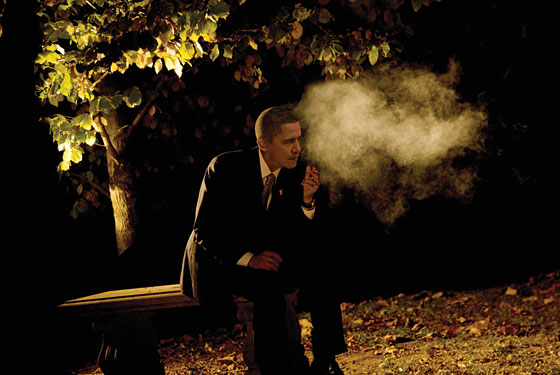

*Real photograph, fake Obama

He opened the door from the West Wing hallway out onto the colonnade, letting Jones pass through it ahead of him. He could already feel the loosening of the skin at the back of his head and the slackening in his jaw. The anticipation alone triggered the letting go.

They walked a few steps along the passageway, the darkened South Lawn drawing their eyes across it to the spot-lit obelisk down on the Mall. The city was quiet.

“This is a difficult one,” Jones said, his hands held together behind his back.

The president nodded. In his jacket pocket, he rolled the filter of the cigarette between his thumb and forefinger. Reggie being out today, he’d had a hard time procuring it. A few hours ago, around midnight, he’d tried his secretary’s desk but found it locked. On the way to Communications, where an aide who worked late usually came through in a pinch, he’d been waylaid by Summers clutching new figures on wholesale inventories in the Southeast, and who would have no more noticed that he was in a hurry if he’d been jogging in a tracksuit. By the time Larry had explained the import of the numbers, he could see Jones over his shoulder signaling that they needed him downstairs.

“The guys in the village—how long have they been informing for us?” he asked, fingering the lighter in his other pocket, wondering how long it had taken his predecessors, the ones who hadn’t been head of the CIA, to get used to uttering lines fit for a Bond film. The number of roles the job required was practically infinite. And each of them had to be played to near perfection. To convince and to mean it and to know every audience better than they knew themselves—that was the talent. It was the power of knowing his own appetites, giving him the time to step back and let others show themselves first, as he calibrated just how much of himself to use for comfort or control. Thoughts he could not share just now, Jim Jones being no ironist. A man who’d mastered Washington as well as the Marines. A player deep in the system. And at six-four, one of the few aides whose eyes he didn’t look down to meet.

“A year,” Jones said. “And the video is crystal clear. The confirmation’s redundant.”

On this still autumn night, the air in the gardens carried a faint scent of the late-blooming roses.

The war didn’t stop for him to review it. It had been over two months since he’d received McChrystal’s report. For weeks now his counselors had been pressing their conflicting stories of what awaited him on the other side of a decision, while the emergencies and the wreckage kept piling up. Along with the choices like the one he faced now.

“Back in June I had a signing ceremony out here,” the president said. “The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. You happen to catch any of that one?”

“No, sir,” Jones said.

“No ads within a thousand feet of a school, and they can’t flavor them like candy. I signed it with ten pens.”

Jones nodded.

“You ever smoke?”

“I have.”

“I’d offer you one,” he said, taking the cigarette out of his pocket, “but it’s the only one I’ve got.”

The expectancy was exquisite. Sheltering the tip with his right hand, he lit it with his left. First came the heat on the lips and then the warmth in the mouth and then his lungs slowly filling. A deep, full breath. Instantly, the calm rose up through the back of his neck, spreading like a flood of perfectly cool water across the surface of his overheated brain. He was in it now—that longed-for gap in time, that merciful pause.

The girls were asleep. The phones were quiet. The media had gone home.

Exhaling was a meditation unto itself.

The speed at which he moved from one performance or task to the next had grown vertiginous. Which, strangely, made the pleasure of executing each one all the keener. Not only to reply by hand to a few of the public’s letters each night, but knowing precisely how to communicate his sincerity through the dark eye of the camera as he explained for the White House website what reading the letters meant to him—there was a pleasure in the exactitude of all this. The strain of it and the pleasure twinned.

A cigarette suspended all that. And for a moment, even here amid the splendor and consequence, it joined him back to the counterlives: the kid who didn’t care about his grades; the freshman listening to the young leftists quote Nietzsche and Foucault; the short-story writer alone in his room after a day miming faith in progress (kneel and you shall pray), believing for a few evening hours that a well-wrought sentence might set people free. Before the organizing principle of Michelle. Before the sorting power of a more concrete ambition. Taking him briefly back to the comforts of the slacker and the cynic. That dark, scattered home promising its own kind of safety.

He took another drag, tapping his ash into a bottle cap he’d grabbed off his desk.

“How long do we have?”

“An hour,” Jones said. “Maybe less.”

He turned and gestured to his Secret Service man.

“Come on,” he said to Jones. “Let’s take a walk.”

The beast pulled up in front of the South Portico and the two men climbed into the backseat. They turned onto 17th Street, passed the Corcoran Gallery, and then took a right on Constitution Avenue.

“They hate it when I do this.”

“I can see why.”

“You ever get death threats?”

“There were a few subordinates who probably wanted to kill me, but the desire for promotion won out.”

“They don’t tell me about most of them. Once you’ve got 500, what’s another 50 here or there? They blend together.

“This is good,” the president called up to the driver, “pull up here.” The three-car convoy came to a halt in front of the Eccles Building and he lowered the window, looking across the wide steps at the Federal Reserve.

“Need some spare cash? I hear they print the stuff.”

Jones smiled tightly.

“This is where I step out. You coming?”

“I’m okay, Mr. President. This is Leon calling. You go ahead.”

With three agents behind and three in front, he crossed Constitution Avenue and headed through the trees and onto the path beside the reflecting pool. It was nearly three in the morning now and the park was empty. It wasn’t a Chicago street in daylight with familiar faces to wave to, but it sufficed. The silence and the open air and the space to think in no deliberate fashion.

He’d gone a few hundred yards, attending to the breeze and sound of his shoes on the dirt, when he detected motion to his right and saw a figure in the shadows rising from a bench.

“Is that you?” the voice said.

The agents had swarmed the man already, one holding his hands aloft while two more checked him for weapons.

“Let’s keep moving, Mr. President,” the head of the detail said, taking his arm.

The interloper was a black man, light-skinned, in his late forties or fifties, dressed in a dark-green rain jacket and suit trousers. “I won’t hurt you,” he called out across the path.

“Mr. President— ”

“It’s okay,” he told the agent. “I’ve got it.”

“Hey, there,” he said, approaching the man, expecting his homelessness to become apparent. But as he got closer he couldn’t quite tell. The man was clean-shaven. He wore black horn-rimmed glasses beneath a high, narrow forehead. His clothes seemed to fit him well enough. The president reached his arm out and they shook hands at a careful distance. The man’s grip was firm. His other hand came up to rest gently across their joined palms, like a minister’s greeting.

“I was just thinking of you. And now here you are.”

“I came out for a walk. It’s a beautiful night.” He drew his hand back. “You enjoy it now, sir,” he said, giving him a smile and a nod.

“I’m your neighbor.”

Half a stride away, the president came to a halt and turned.

“Yeah? Whereabouts do you live?”

“Not far. We could talk awhile. I could walk with you.”

“Mr. President, I’m going to insist— ”

He held his hand up, once again quieting the agent.

Don’t get trapped in the bubble. That’s what he and Michelle and Valerie kept telling each other. There seemed nothing unhinged in the man’s affect. In fact, he seemed oddly calm for a man who’d just met the president in a park in the middle of the night.

“All right, then,” the president said, gesturing to the ground beside him. The man came forward, stooping a bit, one hand held against his side, every motion of his body dissected by the guards.

The two of them began walking slowly along the path, side by side.

“You’re up late,” the man said. “You must have had a long day.”

“Most of them are. You’re out late yourself. You work around here?”

“I have a job at a liquor store. I write in the mornings, or I try to. I was looking through a box in my room today and I found this old paperback Kafka. It starts with one of his parables, ‘An Imperial Message.’ Did you ever read that one?”

The president smiled to himself, surprised and quietly delighted.

“Sure. Years ago.”

It’s the peasant who thinks the emperor’s sent him a message, and maybe he has, but the messenger’s got too far to go to ever make it out of the palace and the capital to deliver it. I like the way he ends that one: ‘But you sit at your window when evening falls and dream it to yourself.’ That’s what got me thinking about you.”

“How’s that?” the president asked, drawn in by the man’s contemplative rhythm. Members of the public were usually so nervous in his presence that all there was time for was to tacitly communicate to them that the encounter was going fine—to, in essence, be with them in their moment of awe, and then usher them on their way. But there was an ease in this man’s voice, a finality almost, and the sound of it undid something in the president.

The man coughed, wincing slightly, before answering.

“It’s like this,” he said. “We’re becoming peasants again. Most of us. There’s the money people and the people around them, and then there’s you. But the rest of us, we’re peasants. And we dream about you. I dream about you. Mostly you and I are talking, sort of like we are now. But the strange thing is that I don’t need a message, I’m there to listen. It’s you—you’re the one who needs to speak. I’m your confessor.”

The agents were right, he thought. This wasn’t safe. The man might be deranged after all. As president, he shouldn’t endanger himself like this.

But then empathy—that was part of the job. He had to mete it out in tiny portions or else risk losing his mind in the suffering of others. But if he shut it down, he was lost. It was the piece of what he knew to be his otherwise virtuosic self-awareness that never moved with the same alacrity. It caught, it snared. It slowed him down.

“What you said about the money people, I get that,” he said, fumbling a bit. “It’s why we need to encourage citizens to organize,” he went on, hearing the hollowness in the talking point.

The man shook his head, either sighing or forcing out a breath, the president couldn’t tell which. As he glanced sidelong at him, he had the uncanny sense that he recognized him. From Chicago maybe, or New York. There was an openness to his face, as if his whole person were close to the surface. A guy, after all, about his own age. But he couldn’t place him, and what were the chances? He was exhausted, he thought, and beginning to imagine things.

“What you say, it may be true,” the man said. “But that’s off in the future. I’m talking about right now. Here. On this path. You’ve got something to tell me.”

“Have we met?” the president asked.

“Not until now.”

“I could have sworn … ”

“I can still walk a little ways with you,” the man said. “You’ve got time to think on it.” For a few moments they proceeded along the Mall in silence.

“I can only imagine how much must go through your head in a day. Is that food up there as good as they say it is? I read somewhere that you had a phone straight to the kitchen where they’ll make anything for you, day or night. Is that true?”

The president chuckled. “Yeah,” he said. “It’s a trip. Nothing but arugula—breakfast, lunch, and dinner.”

At this, the man smiled. But his expression turned quickly into a grimace.

“Could we sit for just a moment?” he asked. It sounded as if he were wheezing now, his breath coming more quickly.

They headed toward the edge of the path as the agents muttered into their mouthpieces, sweeping the area ahead, patting their hands along the bottom of the bench and eventually calling, “Clear.”

“Ah, that’s better,” the man said once he was seated. He was holding both hands now against his side, pressing on his rain jacket.

Glancing down, the president saw a rivulet of red trickle over his knuckles, the blood glistening dimly in the lamplight.

“Sir,” he said. “You’re hurt.”

“It’s nothing,” he said. “It’s just these kids, they came into the store as I was closing up tonight. They’ve been taunting me for weeks. I’ve got my writing notebooks with me in there, behind the glass. And they taunt me. I was waiting for the bus. A few of them came at me. It’s probably nothing, a flesh wound, it’ll probably just heal itself right up.”

He opened his jacket just slightly, and they both looked down at his bloodstained T-shirt.

“Don’t say anything,” he whispered. “Not yet. They’ll take you away. You need to just sit with me. It’s all right.”

The president felt his pulse quicken; the sight of the blood momentarily paralyzed him. He had never seen so much of it.

The man must be in shock, he thought. He’d somehow brought himself down here in a state of shock rather than going to a hospital.

Then, as if in a trance, the president watched his own hand float up and reach across, coming to rest on the wound. The heat of it surprised him. As did the unevenness of the skin, like folds of a wet rag. The man’s flesh throbbed against his fingers. “That’s it,” he whispered. “Go ahead, touch it. It’s okay.” It felt as if the blood were seeping into his palm and rising up into the veins of his arm. “You can tell me,” the man said, in a voice of perfect peacefulness. “Whatever it is you need to say, you can tell me.”

But how could he? How could he say that for the first time he wished he were small? Small enough to slip into this wound, into the pain itself, to give the relentless vigilance up. To slip inside this man he so easily might have been, and vanish. For once he had no words, the wish itself too brief, too disavowed to capture.

He was about to mouth something, to improvise, to reassure the man, but then he felt an agent’s hand on his shoulder. It happened so quickly, the president looking up into his face as they were forcibly parted, seeing in the man’s eyes a look of pure pity.

Before he could orient himself again, he’d been hustled back into the Beast, which turned up onto the grass and was now speeding off the Mall, back onto the avenue, and up 17th Street.

Jones was still there on the far side of the backseat with a file in one hand, a phone in the other. He’d gone stiff and silent, a posture that did little to hide his disapproval and impatience with whatever folly this excursion had led to.

When they stepped away from the car under the South Portico, he heard the cry of an ambulance siren down the hill, headed back from whence they’d come. He and Jones made their way along the colonnade.

“We’ve received final confirmation, Mr. President. We have ten, maybe fifteen minutes.”

With a handkerchief he wiped the red smear from his fingers.

“The target’s still there?”

“Yes.”

“And the others?”

“All of them. They’re all still there.”

“Do it,” he said, turning on his heel, bringing Jones, who was following from behind, up short, his large frame snapping to attention.

Up in the residence, only the lights in the hall and in the small kitchen were on; the rest was a well-padded silence. He went to the cabinet, took down a glass, and poured himself water from the tap. His hands, he noticed, were shaking.

There were private parks, the chief of detail had told him several times already; there were cemeteries that closed at night, places where they could keep him safer if he still insisted on going for walks like this, unscheduled. He would have to do as they told him.

Sensing a presence, he looked up and saw his mother-in-law standing in her bathrobe, watching him from the semi-darkness of the sitting room. He and Michelle and the girls were a talkative family, always jabbering, most always energetic. But Marian had a quiet streak and often his communication with her was wordless—a look or a nod or a grip of the hand. And so it was now. She approached, coming to stand in the kitchen doorway, but she did not burden the moment with speech. She didn’t ask him what was on his mind or if there was anything she could do.

Forty years she’d spent in that little apartment of hers in Chicago, patient as a saint as her husband grew sick and pained and could barely fight his way out of bed. Forty years, and now this. This phantasm of an ending: her grandchildren playing in Lincoln’s house. The girls whose lives she now feared for every day.

He put down his glass and hugged her, knowing that very soon there would be children in pieces in the Hindu Kush, their limbs in the rubble showing up as heat on the reconnaissance imagery, their blood wetting the mortar, dead on the most pragmatic ground. A message sent.

Haslett’s short-story collection was a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize finalist; his novel Union Atlantic will be published in February.