In tone and texture, the New York State party conventions last week could hardly have been more different: the Democratic one ebullient and combative, the Republican one downcast and desperate. But on both sides of the partisan aisle there was a noteworthy element of agreement: that the conventions marked the commencement of the post-Pataki era.

Halfway through his twelfth and final year in office, George Pataki is, incredibly, the longest-serving governor in the United States. For a politician of such proven durability, being buried prematurely can’t be fun. And so it wasn’t terribly surprising that when Pataki addressed his party’s faithful, his speech had a certain Twainish, reports-of-my-death-have-been-greatly-exaggerated undertone. “I’ve got another seven months, starting tomorrow, as your governor,” Pataki declared. “And let me tell you something—I’m not going to stop!”

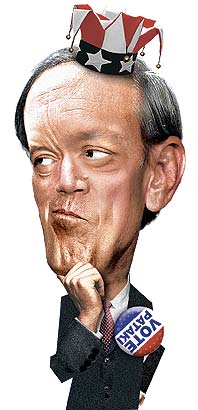

The only sensible reply to this must be, The bland one doth protest too much. For at least the past year, Pataki has given the distinct impression of being an absentee governor. Of being a man whose head is no longer in Albany, but in Des Moines and Manchester. Of being possessed of a belief that’s akin in its degree of improbability to the conviction that Louis Farrakhan should be pope: that Pataki should run for president.

In political circles in New York and Washington, Pataki’s apparent White House aspirations provoke a mixture of amazement and amusement among Democrats and Republicans alike. (“Laughable” is the word used by Hillary Clinton adviser Howard Wolfson; the New York Post prefers “a joke.”) The only person not snickering seems to be Pataki himself. Instead, the governor is courting donors, hiring top-drawer consultants, strategizing with his kitchen cabinet. His last road trip to Iowa was over Memorial Day weekend; his next is two weeks hence. He has trekked to the state half a dozen times in the past year—and surely the number would have been higher had he not been grounded by his epic case of constipation.

All of which raises a number of questions: Is Pataki merely testing the waters on a lark—or does he seriously, honestly consider himself a plausible candidate? Is he a dilettante—or is he deluded? Or, heaven help us, does he actually stand a chance?

Back in February, I flew out to Iowa to spend a couple of days trailing Pataki on one of his exploratory forays. His itinerary was typical of a Republican making the rounds in the Hawkeye State: a dinnertime speech in Sioux City to a modest crowd of Republican stalwarts (the men in sweater vests beneath blue blazers, the ladies in wool pantsuits); a visit to an ethanol factory; a stop at a chili cook-off at a Knights of Columbus Hall; a fund-raiser for Congressman Jim Leach, followed by watching the University of Iowa whip Michigan on the hardwood.

As Pataki hopscotches the cornfields, he emits the dreamy, slightly giddy quality that one associates with those middle-aged guys who attend baseball fantasy camps—he’s Walter Mitty on the campaign trail. At Golden Grain Energy, he proudly talks the talk (“What’s the BTU output in terms of gallonage?”) with the company’s CEO, then strides purposefully across the parking lot to inspect the facilities. It’s freezing outside, and lightly snowing, but Pataki declines to wear an overcoat. His every move is captured for posterity (and future TV ads) by a camera-toting aide (“It’s broadcast-quality,” the kid assures me).

Pataki rarely fails to inform any Iowan who will listen that he grew up on a farm. But much of his nascent stump speech revolves around issues redolent of urban New York: falling crime rates, welfare reform, corporate-sector reinvigoration. When I ask Pataki whether focusing on such stuff carries risks in places such as Iowa, where New York is seen less as another city than as another planet, he replies, “I came here in 1999, and people had a view that there’s America—and then there’s New York. But I think the events of 2001 made people appreciate that we’re all one country.”

Entirely predictably, 9/11 looms large in Pataki’s rhetoric on the hustings. Describing his role that awful day, he says, “I mobilized our National Guard … I talked to President Bush … and I decided that the most important thing I could do was go to lower Manhattan, just walk the streets, not just to find out what was going on, but to let people know that their governor wasn’t running, their governor wasn’t afraid; that we were New Yorkers, we were Americans, and we were not going to cower in the face of these horrible attacks.”

It doesn’t take a genius to discern what Pataki is up to here: He is trying gamely to position himself as the political hero of 9/11. But, irresistible though this maneuver may be, it has a couple of problems. The first can be expressed in two words: Rudolph Giuliani—who already owns the real estate that Pataki is attempting to occupy, and who, of course, has presidential ambitions of his own. (If they both wind up running, it will be like watching a pair of rabid wolverines skirmishing in a sack.) The second is the state of ground zero, which nearly five years after 9/11 remains an utter, shameful mess—for which no one deserves more blame than Pataki, whose management of the rebuilding efforts has been marked by long periods of feckless inattention, punctuated by sporadic bursts of gratuitous pandering, witless posturing, and rank incompetence.

In truth, Pataki has little choice but to talk about 9/11, if only to distract from the issues on which he is out of step with the Republican-primary rank and file. That Pataki is too moderate on social matters—abortion, gun control, gay rights—to pass muster with Christian conservatives is the source of much of the doubt about his prospects among the political cognoscenti. As Wolfson remarked a few years ago in the New York Times, “Pataki is more liberal than many of the Democrats that we had running for Congress.” Or as Terry Branstad, the former Republican governor of Iowa, put it more recently, with delicious understatement, “Pro-choice and pro-gay—those are problems in Iowa.”

“It wasn’t like he was loved when he was in the State Senate. By the end, he had two choices: either run for governor—or run his farm in Peekskill.”

Pataki’s response to such skepticism is an appeal to the old-school notion of the GOP as a big tent. “I’m just going to argue, let’s look at what unites us as Republicans,” Pataki says as we chat at Golden Grain, “and let others do the polarizing.”Put aside the naïveté—Pataki may have a point. It’s possible that Republicans in 2008, on purely pragmatic grounds, may indeed embrace a candidate with some moderate bona fides. But in trying to be that guy, Pataki faces stiff competition.

“I think of the primaries as the Final Four, with different brackets in which the candidates compete to make it to the top tier,” says Dan Schnur, who served as John McCain’s communications director in the 2000 race. “In 2008, you’re going to have the Establishment bracket, where George Allen is probably the top seed; the hard-line bracket, where Sam Brownback is the guy to beat; the outside-the-box bracket, with Mitt Romney and maybe Newt Gingrich; and the maverick bracket of McCain and Giuliani.” Thus the insuperable dilemma for Pataki, according to Schnur: “He’s the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee of the McCain-Giuliani bracket.”

Given the odds stacked high against him, some suspect that if Pataki runs, the job he’ll actually be auditioning for is the vice-presidency. (His wife, Libby, has insisted that “he was on the list” in 2000.) Yet if this is Pataki’s endgame, it strikes me as being nearly as fantastical as his dreams of the presidency. Certainly, any ex-governor of a large and delegate-rich state is automatically a contender for the second spot on the ticket—assuming that he stands a solid chance of delivering his state. Which Pataki, let’s be honest, does not. In fact, according to the most recent Marist poll, his approval rating is a desultory 30 percent—the lowest level recorded by a New York governor in the 23 years since Marist began asking the question.

George Pataki has more than his share of deficiencies, to be sure, but he’s never been lacking in shrewdness. He carefully reads the wind and weather; the difficulty, nay impossibility, of getting anywhere with a presidential run must be no secret to him. So why is he doing what he’s doing? The answer may be, why not? Republican congressman and Pataki pal Tom Reynolds once described the situation Pataki confronted in 1993. “It wasn’t like he was well loved when he was in the State Senate,” Reynolds said. “By the end, he had two choices: either run for governor—or run his farm in Peekskill.”

Today, Pataki faces essentially the same situation—only now he occupies a higher rung on the power ladder, and the farm in Peekskill has been replaced by a 299-acre spread just north of the Lake Champlain shoreline. Pataki has made a career of defying political expectations. Perhaps he nurtures the fantasy that he can do it again; perhaps he thinks a presidential run would be a hoot, no matter how it turns out. But he’d be wrong in either case. Pataki may believe that he’s seen it all in New York politics. Yet as bad as things have gotten for him here—with Eliot Spitzer demonizing him one day and his fellow Republicans doing the same, if more quietly, the next—well, let’s just say they could be worse. Much.

Pataki is always quick to note that he loves the great outdoors. If he grasps what’s good for him, he’ll decide to enjoy it in upstate New York and not in central Iowa. But for the sake of all of us with a sense of humor—or a mild streak of sadism—let’s hope that the fire keeps burning in his belly.

E-mail: jheilemann@gmail.com