On day 46 of the BP oil spill, Barack Obama made his third visit to the Gulf of Mexico since the start of the disaster. And although he didn’t don a wetsuit (as Pennsylvania governor Ed Rendell suggested recently that Bill Clinton would have done were he still in office) or come right out and say, “Message: I care” (as George H.W. Bush once did), the TV pictures of Obama commiserating with the beleaguered residents of Grand Isle, Louisiana, conveyed a message no less blunt or blatant.

For Obama, the trip marked the end of a week spent frantically attempting to corral a narrative spinning out of control. From Attorney General Eric Holder’s announcement of a criminal and civil investigation of BP and others to the president’s speech previewing a renewed push for an energy/climate bill and his decision to cancel (for the second time) his scheduled trip to Indonesia and Australia, every action by Team Obama seemed designed to counter the perception of an administration overwhelmed and impotent—and of a president too cerebral, too stoic, and too supine. As this column went to press, there were signs that BP’s “cut-and-cap” effort to contain the spill just might work. And those hopeful glimmers in turn raised the possibility that the political fallout just might be contained, too.

To which I say: fat chance. With somewhere between 25 million and 50 million gallons of crude already having leaked into the gulf—and that’s the conservative estimate, people—the scope of the calamity facing the country’s southern coast (at least) is already beyond reckoning. As the surface slicks and sprawling underwater plumes approach the shoreline, the economic and environmental costs are bound to be staggering, and the images nearly as irresistible to cable producers as the deep-sea video of the endless gusher. In other words, even after nearly two months, this crisis is just beginning.

The political hurdles confronting Obama, then, remain enormous, possibly even greater than the ones that the accident has presented thus far. But on the flip side of every danger lies an opportunity—and the BP spill is no exception. As much as pulling the country back from the economic brink or passing health-care reform, the catastrophe in the gulf offers Obama a chance to rise to the occasion, and in the process not only validate his conception of progressive, activist, and competent governance but reclaim the visionary mantle that inspired so many during his campaign.

In a way, perversely, this new phase of the crisis should be a cause for relief in the White House. The primary demands on it since the start of the spill have been two: that the administration do something, anything, to get the freaking hole plugged, and that Obama display some semblance of outrage, empathy, or both. But these twin demands have proved to be equally resistant to remedy. Both, it turns out, involve forces of nature—a volcanic undersea geyser, on the one hand, and Obama’s decidedly unvolcanic personality, on the other—apparently impervious to the world’s most advanced technology (in the case of the former) and the cacophonous braying of the punditocracy (in the case of the latter).

In his interview with Larry King last week, Obama tried to put to rest the emotion-free POTUS meme. “I am furious at this entire situation,” he said. “I would love to spend a lot of my time venting and yelling at people. But that’s not the job I was hired to do. My job is to solve this problem.”

A fair point, no doubt, and I suspect that most voters wouldn’t mind Obama’s lack of histrionics if they saw from his administration a response to the crisis commensurate with its scale. But they do not. Confronted with this criticism, defenders of the president have asked repeatedly, What precisely should Obama be doing that he isn’t doing? And the point underlying that question, too, is fair—but only insofar as it relates to jamming or capping the gash in the ocean floor, where BP’s prowess (such as it is) dwarfs the government’s. In the weeks ahead, however, there are at least three broad areas where the Obamans could and should fashion responses as great as the cataclysm at hand.

Legislative. In his speech last week at Carnegie Mellon University, Obama vowed to put his shoulder into passing the comprehensive energy/climate bill awaiting action in the Senate, noting that “the votes may not be there right now, but I intend to find them … we will get it done.” Obama’s words echoed what White House aides have been telling clean-energy advocates privately for weeks. Yet even as they made those assurances, Obama’s political and legislative strategists have been deliberating over how much capital to invest in what could well be a losing cause—for as Obama correctly noted, enacting the legislation will be an uphill push, and one made all the more daunting by the fact that the loosening of offshore-drilling restrictions that was a key to the bill’s passage is effectively off the table.

But now Obama has decided, I am told, to go all-in on bringing the measure home. The question is what the White House believes that going all-in entails. The temptation will be to try and pass it by cutting deals and scratching for votes one by one. But this is not (or not only) a moment for playing the inside game. This is a moment that screams for Obama to turn the bill into a crusade, to hammer home the connection between the BP spill and the need to end our addiction to oil, to shout from the rooftops his vision of a cleaner, greener energy future.

Corporate. The criminal and civil investigations—and, one hopes, prosecutions and ginormous fines—of BP and others are well and good. But they seem too small, pedestrian, and, you know, legalistic (especially since none of the company’s executives is likely to serve hard time) to provide rough-enough justice given the circumstances. The former Labor secretary Robert Reich got a ton of ink when he suggested that Obama place BP’s U.S. subsidiary into temporary receivership. Whatever the idea’s other merits, it would go a long way toward establishing that Obama is, in James Carville’s phrase, the oil titan’s “daddy.”

Even better would be penalties that force BP simultaneously to pay for its sins and contribute to a future where its profitability would be severely undermined. As readers of Daniel Gross’s column in Slate suggested, why not compel BP either to put a nontrivial percentage of its profits or an amount matching dollar for dollar the damages it has caused in the gulf into developing and making publicly available alternative-energy technologies?

Conservationist. The mitigation of the spill’s effects and the cleanup of the gulf—from the ocean itself to the wetlands and beaches of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida, at a minimum—seem destined to be a Herculean task, requiring the work of many thousands of laborers. At a time when the unemployment rate is still hovering near double digits, and when the local economies hit most directly are likely to be decimated, Obama could transform the effort into a massive jobs program, funded not by the government but by BP. At the same time, he could create a new volunteer national-service organization dedicated to the cause. A Democratic operative of my acquaintance has already coined a name for this putative operation: the Gulf Recovery Corps.

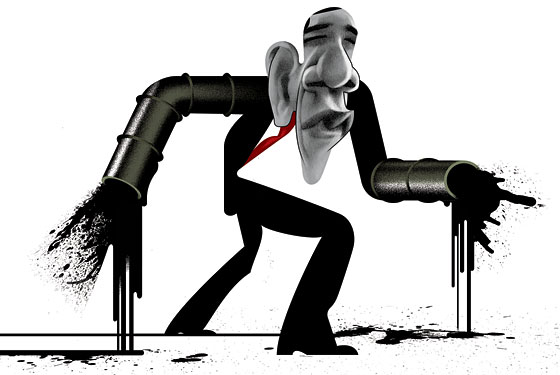

Each of these suggestions has much to commend it on purely substantive grounds. America needs energy reform; BP needs to have its teeth kicked in; the gulf needs saving. But these proposals would also help Obama attend to the political imperatives the crisis has thrust upon him. They would pull him out of his defensive crouch and put him firmly on offense. Executed well, they’d quash the questions being raised by his opponents about his competence. And they would help restore the perception of Obama as a man of big talents and big ambitions ideally suited to a time in history full of big, even epochal challenges.

That sense of bigness was, of course, a signature of Obama’s campaign persona—sometimes to a fault. (One cringes at the memory of him, on the night he wrapped up the Democratic nomination, declaring that future generations would recall that “this was the moment when the rise of the oceans began to slow and our planet began to heal.”) But at times in his presidency, the grandness of Obama’s rhetoric and self-conception has been matched with a more quotidian reality, and the vastness of the problems he’s identified with solutions that seem, if not small bore, inadequate to the task at hand and to their billing.

The BP spill offers Obama a chance to chart a different course—and if he happens to need a road map, history provides one. The launch of Sputnik prodded America to enter the race for space and JFK to pledge to put a man on the moon. The horrors of Selma led LBJ to press for the Voting Rights Act. In each case, a president confronted by a crisis turned it into an opening for progress. If Obama fails to do the same, his political standing may or may not wind up as coated in tar as the Gulf Coast’s wetlands. But he will have missed the kind of historic opportunity that his presidency was built to seize.

E-mail: jheilemann@gmail.com.