Late last September, the Democratic political strategist Doug Sosnik wrote a six-page memo, with a 28-slide deck of charts and graphs, and sent it to his friends and clients—a collection of corporate pooh-bahs, heavy-hitting politicos, and miscreant pundits. The dispatching of memos is something that Sosnik does sporadically, when the spirit moves him.

On this occasion, his topic was one about which Sosnik, who in 1995 and 1996 served as White House political director for Bill Clinton, knows more than a little: the underlying dynamics of how an incumbent gets himself reelected (or not); and, by extension, their implications for the current occupant of the Oval Office.

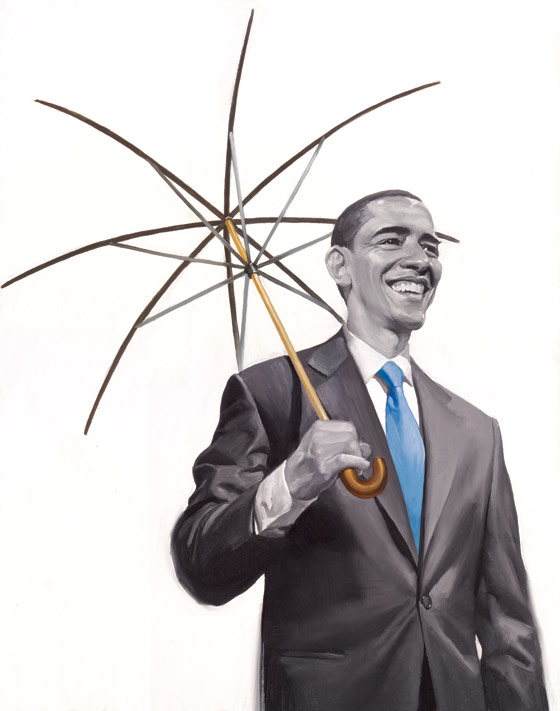

At the time when Sosnik penned his memo, many Democrats were growing increasingly pessimistic about Barack Obama’s prospects for winning a second term. Sosnik was less gloomy, but his point was that the president had to move quickly to address his problems or risk defeat. “Conventional wisdom suggests that Obama’s best chance to turn the corner will come at the beginning of the general-election campaign when he’ll square off with the Republican nominee,” he wrote. “But recent presidential history suggests that it is more likely that Obama’s fate will be influenced more by what he does or does not do in the next several months.”

The next several months, of course, turned out to be good ones—very good ones—for Obama. In his year-end showdown with Republicans over the payroll-tax-cut extension, the president beat the opposition bloody. As the unemployment rate has steadily (if only slightly) declined, his approval ratings have steadily improved. Armed with a retooled and more populist message, Obama has been sharper, more effective on the hustings. His Republican rivals have been engaged in a nasty, brutish, and prolonged spectacle that has simultaneously diminished all of them and exacerbated intraparty divisions that may prove quite hard to heal.

Despite all this, however, few Democrats are ready to start high-fiving or popping Champagne corks—and with good reason. At a time of extraordinary volatility abroad and continuing economic fragility at home, the chances are high that Obama and his team will have to cope in the months ahead with external shocks far beyond their control and of substantial magnitude, any one of which could reduce the historical precedents cited by Sosnik and others to rubble in a heartbeat.

Which doesn’t mean those precedents aren’t worth examining, for they are striking and more than a little counterintuitive (or at least counter to standard-issue Beltway thinking). For all the focus by the press and the political class on the combat that will occur after the Republicans have their nominee—which, the way things are going, could still be many weeks if not months off—Sosnik’s thesis is that, as he put it to me by phone, “in most races where there’s an incumbent president running, the campaign is effectively already over by March.”

In his memo, Sosnik makes the argument more precisely. In four of the five races since 1980 that featured an incumbent, he points out, the sitting president’s job-approval ratings, according to Gallup, were in the 42 to 44 percent range in the second half of his third year in office and the first quarter of his fourth. “What separated the winners from the losers was the trajectory of their approval ratings heading into the general election,” he writes. “[Ronald] Reagan and Clinton were both gaining momentum heading in to the general election, while ratings for [Jimmy] Carter and [George] H. W. Bush were either stagnant or beginning to slide.”

Judging by that metric alone, Obama would seem to be sitting pretty. At the end of August, the Gallup daily tracking poll had his approval rating at an all-time low of 38 percent, with 54 percent of voters disapproving of his performance. Today those numbers are starkly different: 49 percent and 45 percent, respectively. And other polls are consistent with those findings. Last week, a Washington Post/ABC News survey put Obama’s approval rating at 50 percent—a critical threshold for the reelection of an incumbent—for the first time since it fluttered that high briefly in the wake of the killing of Osama bin Laden in May. To Sosnik, the available data suggests one thing: “More and more it looks like Obama is on the Reagan-Clinton track.”

Further buttressing this line of reasoning are the apparent electoral effects of what is taking place in the Republican nomination fight. Though the GOP is trying gamely to comfort itself by analogizing its party’s current knock-down-drag-out to the Obama–Hillary Clinton battle in 2008—from which the victor emerged as a tougher, more appealing candidate—the comparison, at this moment at least, seems absurd on its face. In poll after poll, Mitt Romney, who remains the most likely Republican nominee, has suffered significant erosion in his standing with independent voters. And according to the Washington Post/ABC survey, by a better than two-to-one margin, voters overall say that the more they are exposed to Romney, the less they like him. (For Newt Gingrich, the negative assessment is more like three to one.)

Yet no one with half a brain in his head—and certainly no one with access to Obama’s ear—is under any illusion that a general election against Romney would not be a close-run thing. (A contest against Gingrich or Rick Santorum, by contrast, summons mental images of a stroll along a road paved with red-velvet cake.) For all the damage inflicted so far on the former Massachusetts governor, he is still running even with Obama in many battleground states and with independents nationally. Among registered voters, Romney is rated more highly than the president in terms of his ability to manage the economy and pare down the monstrous federal deficit.

And then there are those potential shocks I referred to earlier. Now, it’s true that external variables are always present in any presidential campaign, and that dealing with them is a persistent challenge for any incumbent. But rarely are they as likely or as potentially threatening as the ones that may confront Obama before November 6. To my mind, there are four:

1. Iran. Early this month, the redoubtable Washington Post columnist David Ignatius reported that Defense Secretary Leon Panetta believes there is a growing likelihood that Israel will attack Iran in the next few months in an effort to dash its nuclear ambitions. If that scenario does indeed unfold, the ensuing crisis and its implications for American domestic politics would be huge—and thoroughly unpredictable.

2. Europe. As of this writing, the fate of the proposed $170 billion Greek financial bailout was unclear, with the country’s political leadership having accepted new austerity measures but elements of its parliament refusing to go along. Yet even if the bailout happens, the risk that a crisis in the eurozone will cascade across the global economy and impact the American recovery will only diminish, not disappear.

3. Unemployment.There are plenty of economic forecasters now predicting that the jobless rate, currently at 8.3 percent, will be below 8 percent by the end of 2012. And if that is the case, it will plainly benefit Obama politically. But at the end of January, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that unemployment would rise again in the second half of this year, to 8.9 percent—and threaten the perception that Obama and his team, at last, have the economy moving in the right direction.

4. Third Party.Both the White House and the Republican campaigns are keeping a close eye on Americans Elect, the well-funded outfit that is on its way to securing ballot access in all 50 states for an independent, bipartisan “unity ticket.” The group’s online nominating process is now under way, though its outcome won’t be known until early this summer. It’s possible, of course, that the Americans Elect ticket—assuming it winds up with two credible, non-crazy personages on it—will take away equally from both Obama and his Republican rival or take more votes from the latter. But it’s more likely, given the kinds of potential candidates that the group has been recruiting, that a vaguely center-left ticket will emerge, thus posing a greater threat to the president.

Of course, it’s conceivable that all four of these potential shocks will come to naught—although nothing about Obama’s first three years in office suggests that he is blessed with that kind of luck. What he and his team have demonstrated in the past five months, however, is sufficient skill and resilience to bounce back from the myriad political nightmares that afflicted them last summer. In doing so, they have not guaranteed Obama’s reelection; far from it. But they have put themselves in the best position possible for any incumbent, and especially one facing off in the fall against this particular crop of Republicans: the position to turn the general election into a choice and not a referendum.

E-mail: jheilemann@gmail.com.