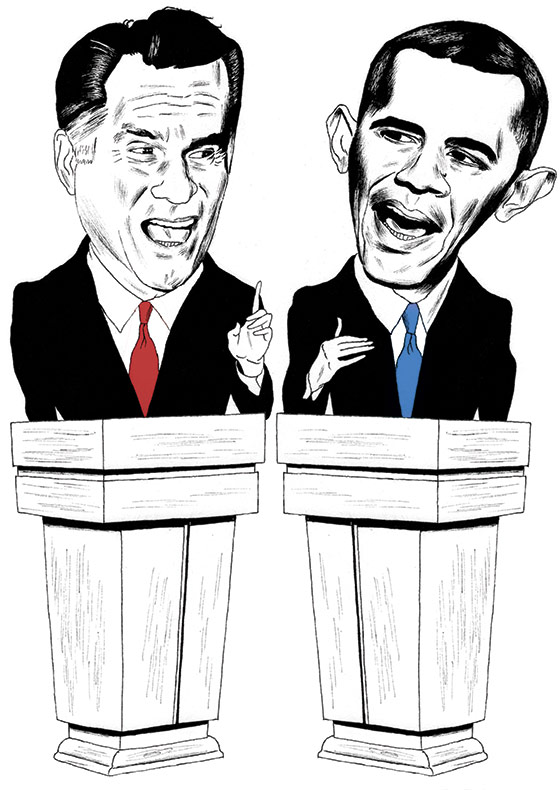

When Mitt Romney took to the debate stage at the University of Denver Wednesday night, he was shouldering both a blessing and a curse. The blessing was that of expectations so low they were practically subterranean: According to the polls, voters believed by nearly a two-to-one margin that Romney was fated to be beaten by Barack Obama. The curse was that of an almost impossibly high bar to clear in order to be seen by the political-media class as having won. He needed to alter fundamentally a campaign dynamic that was ushering him inexorably to Loserville. He needed to challenge Obama forcefully while improving his dismal favorability ratings. He needed to be tough but likable, aggressive but not assholic. He needed to be convincingly presidential but also recognizably human. He needed, in other words, to be the Mitt Romney whom no one has glimpsed for, oh, the past six years that he’s been running for the White House.

And then, lo and behold, he was. Now, to be sure, the effusiveness of the post-debate praise for Romney on the right was at times over the top. (No, Michael Barone, he was not Sitting Bull at Little Big Horn.) But Romney was clear, crisp, confident, and in command of his bullet points. His indictments of Obama were energetic but not shrill. He came across as a pragmatist, a manager, a moderate and not an extremist—like the Romney who ran for office in Massachusetts in 1994 and 2002. That Romney was always a plausible president, and his sudden appearance made you wonder: Where the hell has this guy been?

Then there was President Obama. It would be easier to grade his performance had he bothered to show up. Obama was the man who wasn’t there—passive and pedantic, enduring the experience rather than engaging it, not an ounce of verve or fight or passion in him. Some wags joked that Obama seemed to be debating as if he were on Ambien. Well, I know Ambien. Ambien is a friend of mine. And this was no Ambien performance. It was more like Obama had been sucked into a K-hole, or was suffering from aphasia.

The question, of course, is what the actual, tangible effect of the debate will be—and the answer is that it all depends on what happens next. History tells us that presidential debates rarely alter the electoral outcome, and the drop of the unemployment rate to under 8 percent for the first time since Obama took office may prove more consequential. But make no mistake, this debate mattered. Overnight, the wind and weather of the campaign shifted, and Romney, on the brink of entering a Bob Dole–like death spiral, was endowed with new life.

The avoidance of that spiral was, in fact, Romney’s paramount achievement. After a horrific month of September, much of the Republican Establishment and its donor class were close to abandoning him as a lost cause and turning their efforts (and channeling their dollars) to House and Senate campaigns. But the drubbing Romney administered to Obama foreclosed that dire possibility. Never mind that he extended a stiff middle finger to the fire-breathing right by recasting himself as Moderate Mitt. After weeks of having a likely loss jammed down their throats, conservatives thrilled at the taste of victory on their tongues. So in addition to the war whoops that went up on Thursday morning, the other sound you heard was that of checkbooks being opened and pens scrawling out donations to the super-pacs whose spending will enable Romney to stay competitive in the last month of the race.

Romney’s second big accomplishment in the debate was earning himself a second look from the sliver of the electorate that remains undecided. For those voters, Romney has been largely defined as a plutocrat whose policies favor the rich and who has no comprehension of the struggles of ordinary people. How much did his debate performance move the needle with them? The polling will tell us in the days ahead. But it’s worth noting that because the relevant topics didn’t come up, nothing Romney said in Denver is likely to remedy his problems with Hispanics, women, and other key demographic groups that prefer Obama by wide margins—margins that in turn undergird his slender but meaningful advantage in the battleground states.

For Romney, the challenge now is to capitalize on the opening he cleared for himself. In the past, he has demonstrated an unerring propensity to follow up on any triumph by inserting both of his wingtips simultaneously in his piehole. The day after Denver, Romney played it safe, doing a single campaign event (with fireworks!) and an interview with Sean Hannity, in which he continued his latest reinvention by renouncing his denunciation of 47 percent as irredeemable moochers as “completely wrong.” But with more than a week to go before his next debate with Obama at Hofstra University on October 16, Romney will be faced with ample opportunities to enhance his new, improved image or revert to form. Which Mitt Romney will we see? Your guess is as good as mine.

But here’s the crazy thing: For the first time in a long time, many Democrats are asking the same thing about Obama—so perplexed, confounded, and just plain pissed off are they about his dismal turn in Denver. The mystery of what happened to the president there is perhaps a bit less mysterious than it seemed on first inspection. Five factors, I think, were at work.

First, for weeks now, the Obama campaign has been playing it safe, sitting on its lead, executing a four-corners offense and a prevent defense; Obama’s low-altitude, low-risk speech in Charlotte was part of that game plan, which in Denver amounted to an effort to avoid unforced errors. Second, consistent with that, Obama had been advised essentially to ignore Romney and talk directly to voters; as his strategist David Axelrod put it the next day, “He made a choice last night to answer the questions that were asked and to talk to the American people about what we need to move forward, and not to get into serial fact-checking with Governor Romney, which can be an exhausting, never-ending pursuit.” Third, Obama’s team is intensely focused on preserving his main electoral advantage, which is his likability. Indeed, much of his debate prep was spent coaching him to contain his simmering disdain for Romney; onstage, that seems to have translated into Obama’s studious refusal to make eye contact with his rival. Fourth, incumbent presidents become accustomed to being accorded unceasing deference (and gratuitous toadying); it’s been four years since anyone got up in Obama’s grill and told him he was full of shit, and the shock of it was palpable. And fifth, Obama was prepared to debate the Romney who has been on display for the past two years, the Romney imitated by John Kerry in debate prep—a very different Romney from the one who took the podium. Like the rest of us, Obama was gobsmacked.

To be abundantly clear: These are explanations, not excuses, for there is no excusing the inexcusable. Obama’s advisers, and Obama himself, are appropriately chastened about what transpired. In the aftermath, I asked a campaign official if we would see a different Obama at Hofstra. “We’d better and we will” came the reply.

Obama’s people took some comfort in the notion that Romney’s victory was purely stylistic—and that on substance, he had opened himself up to new lines of attack. On taxes, Medicare, and much else, the GOP nominee’s performance was littered with evasions, distortions, and outright falsehoods. “It was a very vigorous performance, but one that was devoid of honesty,” Axelrod said.

But Romney’s late-stage repositioning presents a strategic conundrum for Obama’s campaign. Earlier this year, when it became clear that the former Massachusetts governor would be their opponent, Team Obama wrestled with two different, and at least ostensibly contradictory, framings of Romney: on one hand, as a flip-flopping phony, and on the other, as a right-wing extremist. Bill Clinton, among others, advised the campaign to abandon the former and embrace the latter. “They tried to do this with me, the flip-flopper thing,” Clinton counseled, but “it just doesn’t work”—because voters don’t mind so long as the candidate is flipping and flopping in their direction.

The Obamans came to agree, jettisoning their condemnations of Romney as coreless. Instead, just as they had done to John McCain in 2008, they relentlessly sought to portray Romney as a clone of George W. Bush—and as pursuing an agenda indistinguishable from that of the tea-quaffing congressional Republicans, which swing voters look upon unkindly. And Romney, somewhat mystifyingly, played right into the caricature.

At the debate in Denver, however, Romney’s long-awaited Etch-a-Sketch moment finally arrived. Now Obama confronts a choice: stick with assailing his rival as an extremist, shift to pummeling him as a flip-flopper, or synthesize the two angles of attack. Almost certainly, Obama will embrace the synthetic approach—and, n.b., it can be done, as Bush proved in 2004 against Kerry. The Democratic bed-wetters (as David Plouffe called them in 2008) are already in panic mode, worried that Obama has lost his mojo. Chances are that they will be proved wrong, that Obama will raise his game in the final innings as he has so many times before. But if Hofstra turns out to be another Denver, what is now a sprinkle will become a flood, and with good reason.

See Also:

• Chait: Can Obama Discredit the New Romney?

• Rich: Obama’s Ambien-esque Performance

E-mail: jheilemann@gmail.com.