Rosie O’Donnell is standing next to Martha Stewart on the Chelsea set of Stewart’s talk show. O’Donnell is here on a frigid February morning to make a chocolate-pudding cake and to talk about Rosie’s Shop, an online store that benefits her children’s charity. They make an odd pair: The erstwhile host of The Rosie O’Donnell Show is loose and spontaneous, the class clown to Stewart’s student-council president.

“There’s a brand-new sign on the way into the studio,” O’Donnell announces to the audience. “It says WIPE YOUR FEET.”

“She hasn’t been to my house yet,” Stewart says. “Every door says REMOVE YOUR SHOES. All little notes, everywhere.”

“Do you think it’s rude to people?” asks O’Donnell, hastily sweeping up some cocoa that she’s spilled.

“Nope,” says Stewart. “I got a whole box of those little socklets that have the rubber on the bottom.”

“See, that’s why everyone in America loves you,” says O’Donnell. “Because you provide socklets with rubber on the bottom for people who come to your house.”

The crowd eats it up. “I miss Rosie,” says a woman in the audience. “I used to go to her show all the time. They put Drake’s cakes and milk on the chairs.”

After the show, Stewart retreats to her silent, austere office to check her computer before a meeting. “Rosie is always lively, always loud,” she says. “She’s incorrigible and lovely at the same time.”

Down the hall, in her dressing room, O’Donnell is surrounded by a pack of Martha staffers, many of them veterans from her own show. I ask O’Donnell what she and Stewart were chatting about during the commercial breaks (it was mostly O’Donnell doing the talking while Stewart would nod vigorously). “I asked her how the show was going, and she said she was very tired, and I said I understood,” O’Donnell says in her signature Long Islandese. “I told Martha I don’t have a mother and asked if I can call her, and she said yes, which I loved. And that I think I’m in perimenopause. I’m getting night sweats, and for two months, I thought I had aids, but I’m in a very low-risk group. Lesbians hardly ever get AIDS. I realized maybe it’s menopause. I think I have bird flu if I get a pimple. I’m a bit of a hypochondriac. And I told her I got my skin tags cut off. She said, ‘What are skin tags?’ I was like, ‘Do you mean to tell me you’ve never had a skin tag, so I can feel worse about myself?’ ” She shrugs. “I wanted to ask her questions about my adult acne and stuff like that, but there isn’t time when you’re making chocolate pudding.”

The removal of her skin tags is actually not news to readers of O’Donnell’s year-old blog, rosie.com. Back in January, Rosie wrote, “last week i had 3 skin tags / removed / the dermo zapped em off / nearly pain free / as i applied the numbing cream as directed / pre visit.”

So that’s what Rosie has been up to.

Not so long ago, Rosie O’Donnell seemed destined to be another Martha Stewart. Or Oprah. She was funny and endearing and empathetic like few others in the public eye—an American Everywoman, the celebrity next door who loves Target, struggles with her weight, and, as she puts it, reminds you of “that girl down the street, Eileen, who’s on the bowling team. You know the one—she doesn’t have a boyfriend? She mows her lawn a lot.” As host of The Rosie O’Donnell Show, she was one of the most popular daytime-TV personalities ever. Good ol’ Rosie, collector of Koosh balls, belter of show tunes, doer of good deeds for underprivileged kids! Not for nothing was she dubbed “the Queen of Nice.”

Then her image took a series of major hits. She walked away from her talk show in 2002, even as Warner Bros. threw outrageous sums at her, exhausted by the grinding pace and sick of Hollywood phoniness. “When I did interviews, nobody really wanted to talk-talk,” she says. “It was all kind of short and surface.” At the time, her career plan was to put all of her energy into her namesake magazine, which she had started the year before. She also came out as a lesbian, promptly acquiring “the dykiest haircut you could get,” she says. In October 2002, O’Donnell found herself in an ugly breach-of-contract lawsuit with publisher Gruner + Jahr. During the trial, a number of embarrassing details emerged, including her now-infamous alleged “liars get cancer” remark to an employee. Then, in the fall of 2003, O’Donnell’s $10 million Broadway production of Taboo was fricasseed by critics and folded after three months. O’Donnell has surfaced since then—in last May’s TV movie Riding the Bus With My Sister; on Broadway, in Fiddler on the Roof, this past winter—but for the most part, she has been conspicuously off the radar. This from someone who had, over two decades, churned out a memoir, a monthly magazine, two books, three Broadway shows, two Christmas albums, and top-grossing movies—A League of Their Own, Sleepless in Seattle, and The Flintstones—three years running. In 2000, O’Donnell hosted the Grammys and the Tonys; she racked up six Emmys for her talk show, for which she was paid more than $25 million a year. Her net worth at the time was estimated at over $100 million. Then—poof.

Rosie O’Donnell, it turns out, decided to give fame the finger. Yes, she admits that the film and TV offers slowed after the trial and Taboo debacles, and, yes, with millions in the bank, she can afford the luxury of dropping out. But while other smacked-down celebrities would have begun feverishly engineering their comeback, O’Donnell retreated to her home upstate, along the Hudson River, where she began spending most of her time with her partner, Kelli O’Donnell (the two were married in 2004 in a civil ceremony in San Francisco), and their four children—Parker, 10, Chelsea, 8, Blake, 6, and Vivienne, 3 (the oldest three are adopted; Vivienne was born to Kelli in 2002).

O’Donnell had set up a crafts studio a short walk from the house that she, Kelli, and the kids live in, and after Taboo closed, she hunkered down there for hours a day. For the better part of a year, she used art as therapy, painting and sculpting furiously, taking the most brutal press clippings and making them into découpages and collages. Soon enough, she had piled up more than 5,000 works. During that time, O’Donnell reached a conclusion she had been slowly arriving at for years: She was going to be fully herself.

Now, instead of being a multiplatform, global entertainment-and-lifestyle brand, the 44-year-old O’Donnell is doing pretty much whatever she damn well pleases. If she wants to hang out with Kelli and the kids, she hangs out with Kelli and the kids. If she wants to paint, she paints. If she wants to do a little Broadway, she does a little Broadway. If she wants to blog, she blogs. If she wants to launch, say, an all-gay family cruise line, she launches an all-gay family cruise line (R Family Vacations, founded by O’Donnell, Kelli, and Gregg Kaminsky, a travel-industry friend, staged its first cruise, to the Bahamas, in 2004; the trip is the subject of the HBO documentary All Aboard! Rosie’s Family Cruise, airing April 6).

O’Donnell says she does not miss her old life. She says she always had a plan of doing the talk show for five years, then getting out. It stretched to six, and then she was done. “Six years of megastardom, that was intense,” she says. “I needed to refuel myself with real life.” She says she can relate to Dave Chappelle’s rejection of a $50 million deal from Comedy Central, especially because the popular assumption is that if you walk away from a pile of cash that massive, clearly you have gone coconuts. “There’s only one goal in show business, and that’s more,” O’Donnell says. “You can have an Oscar and you need more. It’s gross excess.”

O’Donnell’s goal, she says, has always been to reach 40—her mother died from breast cancer at 39—then retire and have the next part of her life be the one that her mother did not get to experience. “How do you want to spend your life?” she says. “Would you like to be adored by the masses or known by your children? Because you can’t really do both.” Early retirement, in fact, has been a lifelong dream. “I used to say in my act, before I had my TV show, ‘Why isn’t Oprah Winfrey on an island in Barbados with Stedman?’ ” she says. “Everyone was like, ‘Oh, when you get there, you wouldn’t do it.’ Uh, yes I would! I would take Stedman and go, ‘Honey, come with me, we’ve just bought Hawaii. We never have to work again! Cheers, Stedman!’ That’s what I would do. But I’m not her.”

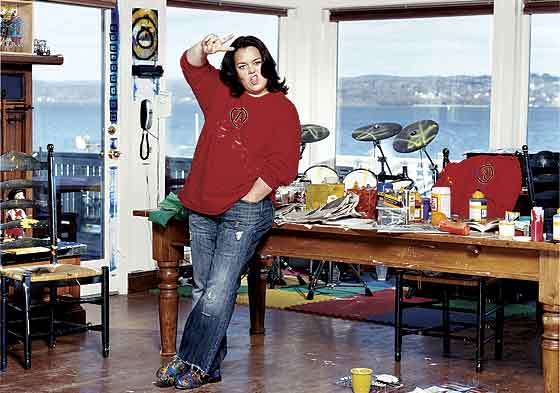

The door is open at Rosie O’Donnell’s crafts studio, a bright, modern space with high ceilings and huge picture windows, perched above the Hudson. “Isn’t this great?” O’Donnell asks. “It’s like I created my own playroom for grown-ups.” An explosion of artwork covers the walls: huge paintings in blue, green, and yellow, collages, shadowboxes, wire sculptures. Paint cans, colored pencils, and beads are neatly arranged on a shelf; there’s a potter’s wheel and stacks of canvases.

O’Donnell, makeup-free, is wearing a black T-shirt, blue Adidas track pants, and yellow gardening clogs. “I’m cheap on clothes,” she says. She would never pay $200 for a pair of jeans, she says, preferring instead to spend money on computer equipment (for her blog) and cameras (to take pictures of her kids). She recently dropped quite a bit of weight. “I lost 25 pounds during Fiddler,” she says, sticking a Yaz CD into a player. “I’m under 200 now.”

O’Donnell looks around the room with satisfaction. “When little kids come in here, they lose their minds,” she says, taking a seat at a table and picking up a brush to paint white dots on a box. “Of course, my kids think it’s totally normal to ask for a six-foot canvas and have every paint color they want. I think it’s going to ruin their lives. We can’t get our 10-year-old to behave at school. And every other parent goes through this in America, just so you know.”

She picks up another paintbrush, adds some blue squiggles to the box. “Isn’t this peaceful? The really scary thing is that I’ve been doing this since May 23, 2002, when I left my show.”

Since that time, O’Donnell’s days have unfolded with what she says is a comforting sameness. She wakes up around nine and heads down to the kitchen. Kelli has already taken the kids to school—and has left Rosie some lunch (“something healthy, like tuna fish and a salad, so I don’t eat Cap’n Crunch”). Then O’Donnell goes to the studio, where she paints and draws until it’s time to pick up the kids from school at 2:30. She TiVos Oprah every day but doesn’t watch other talk shows as regularly. She will occasionally catch Ellen DeGeneres, although when Barbra Streisand was on in the fall, “it almost made me want to kill myself,” she says (O’Donnell famously shared a love of Streisand’s music with her late mother, and was so emotional when the singer was on her own show that she’s still unable to watch the videotape). After watching the singer on Ellen, O’Donnell phoned her former producer, now with DeGeneres’s show, and said, “I’ve never been depressed or jealous or anything, but when I saw Ellen with Barbra Streisand, I wanted to jump off a cliff. Just because I felt the lack of reverence was so horrific to me.” She shrugs. “But who knows who Ellen’s Barbra Streisand is?”

With Kelli and their four children, O’Donnell has constructed the traditional picket-fence sort of life that eluded her as a child (Rosie’s mother died when Rosie was 10). O’Donnell and Kelli’s life now is almost sweetly retro, the Cleavers with two Junes instead of June and Ward. There are picnics, bowling nights, boat rides on the river, soccer practice, family dinners together every night, and weekends filled with playdates and pizza. The children don’t watch TV, so at night the family plays games like Uno. Sometimes the women will vacation separately with one child, to make each feel special: Rosie took Parker on a cruise to Alaska, and Kelli took him to Rome.

Rosie says that in every couple, one person is the flower and the other is the gardener. Kelli, Rosie says, is the gardener. A pretty blonde with clear blue eyes, the 38-year-old Kelli avoids the spotlight, or at least tries to. “Even though she has no desire for the public part, it comes with it,” says O’Donnell. “She told me, ‘When I had to do public speaking for Nickelodeon, I had to take a beta-blocker.’ ” (Kelli is a former Nickelodeon executive.)

It is Kelli who manages the family’s business and personal affairs, from R Family Vacations to their life at home. Rosie plays with the kids, but Kelli supervises the homework. “She creates and enforces boundaries, and she’s a natural provider,” says O’Donnell, getting up to put a bag of popcorn in the microwave (“What do you think, four minutes?”). She brings it back and puts it in the middle of the table. Kelli is calm and composed, where Rosie is messy and emotional. “I’m always like that Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon,” O’Donnell says. “You know how there are only, like, twelve of them, and it takes a hundred people in order to get them down the street safely for one day? And they have to all be synchronized and know how to move in unison in order not to let this big, big thing not crash into a pole and kill someone? She’s like the main tether. She gets me down the street without killing anybody.”

O’Donnell started rosie.com in February of last year. After Taboo ended, she began to drive her friends crazy with a flood of e-mails, and one of them ultimately suggested she start a blog. The blog is a mix of musings about celebrities, anti-Bush diatribes, and glimpses at O’Donnell’s life with Kelli and the kids. O’Donnell once described it at the top of the page as “the unedited rantings of a fat 43-year-old ex talk show host married mother of four.” By far the most numerous, and pointed, comments appear under the header In the News, in which O’Donnell takes on subjects like President Bush’s wiretapping (“now will someone call for impeachment / come on America”), James Frey (“the gay guy coming on 2 him / one 2 many times / his brusk rebuttal / suspect”), and Karl Rove (“karl rove is a criminal creep / his day will come”). The war in Iraq is an obsession, as is celebrity, but she is just as likely to do a post about the Schick Intuition razor (“the best invention / since the tampon multi-pack”).

When O’Donnell started the blog, the reader-comments section filled up with hate messages of the “You’re a fat dyke” variety. “There’s always going to be people who think you’re an asshole,” O’Donnell says. “Chances are, whatever they’ve written, I already believe about myself. Every dark thought, I’ve already had about myself. Everyone goes through that, thinking they’re unworthy, they’re talentless, they’re stupid, they’re fat.”

O’Donnell, mind you, sometimes has dark thoughts about others. “Pilates my ass,” read a recent post about Star Jones. “That’s how she said she lost 200 pounds,” O’Donnell says, her voice rising. “Here’s what annoys me about Star Jones. As a former fatty, she has an obligation to her tribe. And to write a book about how to be the perfect woman that she now is, and to leave out gastric bypass and the supposed gender-identity issues of your husband, it’s just like selling bullshit to the point that it’s sickening.” She shakes her head. “She pretends that she was never one of us. And she pushed away a plate of Oreos with Joy [Behar, co-host of The View]. They had new Double Stuf Oreos they had to eat obviously because they had a Nabisco deal at ABC, and Star goes, ‘I’ll just have one, because I have self-control.’ And I thought, Joy’s gonna say it. She’s gonna say, ‘You lying sack of shit, you can only eat one because you poop soup!’ Authenticity is the only thing that people want to buy. If you give them the choice between loving Star Jones lying or loving Star Jones telling the truth, they’re going to love Star Jones telling the truth.”

“Why isn’t Oprah on an island with Stedman? I would take him and go.”

O’Donnell and her four siblings grew up in a middle-class household in Commack, New York, raised by her homemaker mother, also named Roseann, and her father, Edward, an engineer for a defense corporation. Rosie adored her mother, and they bonded over two things, show tunes and Streisand.

When Roseann was dying, a young Rosie decided that she would become famous, reasoning that if Streisand’s mom were sick, Streisand would be able to go on the Tonight show and ask fans to send in money. “I thought fame and the fantasyland of movies would save me,” she wrote in her 2002 memoir Find Me. “I was certain it would protect me from scary dreams and dead mothers.”

O’Donnell did her first stand-up gig at 16 at an open-mike night at a Mineola club called the Round Table. She shakes her head. “If my kid at 16 said, ‘By the way, I’m going to Vinnie’s Yuk Yuk Palace with a bunch of 30-year-old men, I’d be like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ It’s the fact that I had no parents giving me any kind of limits that allowed me to go do what I wanted to do.” (Rosie’s father maintained the household, but wasn’t emotionally there for the kids after his wife died, O’Donnell says.) O’Donnell dropped out of Boston University at 18 to work the club circuit, being picked up at airports by strangers from the clubs and staying in cruddy hotels. The break that launched her career was a 1984 appearance as a finalist on Star Search.

O’Donnell still dreams of her mother, she says. “The latest one was that she was alive and had a whole family of kids in their twenties,” she says. “My brothers and sisters and I pulled up to this nondescript suburban house and saw her through the window with these 20-year-old kids who were now her family. She had left us to be with them, and no one told us, and somehow we found her and were going to meet her and all of her children. It was intense.” A friend once asked O’Donnell if she would ever get over her mother’s death. “I remember thinking, No, I probably will not.” She shrugs. “I don’t know what you do.”

It is a cloudless July day, and the cruise ship Norwegian Dawn is sailing from New York for Nova Scotia. Some 2,200 giddy passengers are aboard for R Family Vacations. Excited kids of all hues are racing through the hallways or being photographed jumping into the pool by their doting same-sex parents. Founded in 2004, when Kelli and Kaminsky realized, after vacationing themselves, that there were no cruises for gay families, the operation is now in its third year. The first trip was to the Bahamas (that’s the one chronicled in All Aboard! Rosie’s Family Cruise, which was received with a standing ovation when it was premiered at Sundance and has since won enthusiastic reviews), then came the Nova Scotia journey last summer. This summer, one ship will head to Alaska, and another will leave for the Galápagos in November. A Caribbean trip is set for February 2007.

Because O’Donnell arranged the talent, the ship is teeming with gay and gay-friendly celebrities. Cyndi Lauper is set to perform. Sharon Gless of Cagney & Lacey will screen an episode of Queer As Folk. Mario Cantone will be spotted in line at the chocolate buffet (“I’m just looking, I’m not eating anything”).

Easily the most anticipated event is Rosie’s Variety Hour in the Stardust Theater, on night two. O’Donnell takes the stage to thunderous applause, and then she brings up Tom Cruise. At the time, O’Donnell’s beloved friend had just attacked Brooke Shields for using Paxil to treat her postpartum depression.

“Cuckoo!” she screams, and the crowd goes bonkers. “He says there’s no such thing as a chemical imbalance? He should come over on a Friday night, and I won’t take my meds!” She paces the stage. “I’m very concerned that my Tommy went off the deep end. I saw him with Matt Lauer, and I had to take a Xanax right after. He looked like he was having a bipolar episode right there.”

Over the next six days, ten couples will get legally married on Pier 21 in Halifax, extra chairs will be brought out for the jammed Surrogacy and Egg Donation workshop, and little kids will wave glow-sticks during “If You Were Gay,” performed by cast members of Avenue Q. Cruise passengers typically stay in little pods, maybe meet a few couples. On this trip, just about everyone on the ship has bonded. When it’s time to go, many of them cry and cry.

Besides launching the cruise line, O’Donnell has donated or raised millions of dollars for dozens of charitable groups, from the American Cancer Society to Broadway Cares to the Red Cross. Her foundation Rosie’s Broadway Kids, which offers theater instruction to underprivileged kids, recently bought a building on 45th Street; a $4 million renovation is in the works. O’Donnell’s life’s dream is to revamp the nation’s foster-care system. “The gay community can help solve the foster-care problem, because they are dying to parent and they know what it’s like to be unwanted,” she says.

“What I like about Rosie,” says her friend Madonna, “is that she has taken all her pain and reinvented it as compassion. She is generous to a fault.”

O’Donnell says her munificence has an edgier, more selfish side. “Overly generous people, people whose need to give is nearly pathological, there is something behind that, an unworthiness, a sense of guilt that they shouldn’t have as much as they do,” she says. Her mother’s death, she says, also explains why she does so much to help others, especially kids. She blurs the line, she says, between herself and them.

O’Donnell is back in her crafts studio, painting. She’s developing a sitcom, she says, with Alice Hoffman. It’s about an Erma Bombeck–esque Newsday columnist who has lost her girlfriend to breast cancer. She is also set to star in an upcoming Broadway drama, Folding the Monster, with Danny Aiello.

O’Donnell insists, however, that she no longer wants to be seen mainly as an entertainer. “When everyone wants to relate to you as that one slice of pie that they’re seeing for an hour a day—I mean, that part is true and real, that’s not a con. But, you know, there’s twelve pieces in a pizza. There are other parts—there is the political part, the gay part, the depressed part. There’s the overweight part. There’s the happy part. There are all different parts, like everyone.”

O’Donnell puts down her paintbrush. She wants to be a philanthropic brand, à la Paul Newman, she says. Other than that, she has no plans. “My whole life was, my mother died before she was 40, so I thought if I got to 40, I might be able to make it. I might be able to live like my grandmother to 78,” she says. O’Donnell likes to ask people this question: If you could be guaranteed to live to a certain age, what number would you take? “I’d take 78 right now, you kidding me?” she says. “I always ask everyone that, and they go, ‘I’ve never thought of that.’ I’m like, ‘It’s all I think about!’ Would I take 63 as a guarantee? Let’s see. I’m 44; at 63, my daughter Vivie will be 22. To guarantee I’d get there? I might.”