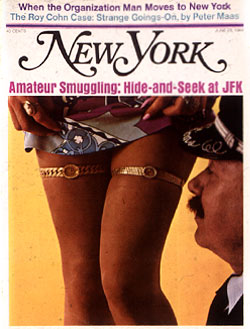

From the June 23, 1969 issue of New York Magazine.

“It’s up to you, Jeff, to save the white race.”—Jack London to James J. Jeffries on the eve of Jeffries’ fight with Jack Johnson in 1910.

In the ski lodge at Grossinger’s, a tall, lanky sparring partner named Alan Boursse played listlessly with a speed bag. He slapped it gently, listening to the sound echoing around the room, then ripped off a barrage of punches, then grabbed it in his hands to quiet it and walked away to look out into the gray afternoon at the workmen repairing the ski slope in the distance. The audience watched him the way people watch the inhabitants of zoos.

“This is a fine young boxer, ladies and gentlemen,” the announcer was saying. “He will be boxing today with the next heavyweight champion of the world!”

About ten after three, the man who might be the next heavyweight champion of the world walked briskly into the large room.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Jerry Quarry has now arrived,” the pitchman said. “Jerry Quarry, who fights Joe Frazier for the title on June 23 at Madison Square Garden! He’ll begin boxing shortly.”

Jerry Quarry was dressed in natty gray sharkskin trousers, a cobalt-blue shirt and white shoes, and he looked like all those young men in Southern California who don’t take drugs or wear their hair long or go off to Berkeley. The dark blond hair was combed straight back, with long sideburns, and you were sure that a few years ago he wore a ducktail. The face itself had that rugged blockiness you see a lot in California: straight short nose, good jaw, neat ears; only Quarry’s eyes had that peculiar maturity that comes with the acceptance of pain. He nodded and disappeared into the dressing room.

After awhile, Quarry returned and hopped into the ring. He was wearing green trunks and white boxing shoes, and he started to move briskly around the ring, flicking his bandaged hands at the air. The hard body was tanned and trim, and he twisted it and stretched it, the hands always moving, describing patterns of punches, the jab whipping straight out, the right hand jamming behind it, the short flat hook whipping horizontally across Quarry’s own chin-line. The audience seemed hypnotized.

Then Quarry went over to the side of the ring, where his trainer Teddy Bentham smeared Vaseline on his face and laced on a pair of 10-ounce red boxing gloves. Boursse came into the ring, his face masked by headgear. Quarry did not wear headgear, and you could see the blanched look on the face of John Condon, the Garden public relations man. Quarry’s fight with Frazier is the hottest prizefight of the year; the Garden might be sold out, and if it is, the live gate alone could be $750,000, with another million coming from closed-circuit television. If Quarry were cut in training it would cost someone a lot of money. But Quarry is a fighter, and the real fighters don’t really care much for headgear.

Bentham shouted, “Time!” and the fighters moved at each other. Quarry jabbed, threw a vicious hook to Boursse’s side, and then brought the hook up to the head. Boursse held, and Quarry pushed him off and went at him again. For two rounds it went that way: Quarry pursuing, Boursse retreating, and Quarry landing thunderous body punches.

Once, in a corner, he made a move that the good ones take a long time to learn: he threw a left hook-right hand to the body. Most fighters stop at that point and hold on, or come up with swinging hooks to the head. Quarry leaned in, as if to hold Boursse, then stepped back an inch and ripped off a tight fierce uppercut that went between Boursse’s gloves to the chin.

“He hits Frazier with that punch, Frazier goes,” said Bentham, a small, intelligent man who went to St. Anthony’s School in the Village and now lives in L.A. “That is a sweet punch.”

Watching Quarry work, I realized suddenly why I was as transfixed by the exhibition as the audience was. Quarry was white. And he was good. I’ve been around fighters and training camps most of my life, but those camps have always involved black men or Puerto Ricans: Jose Torres, Floyd Patterson, Sonny Liston, Muhammad Ali, Emile Griffith, others. With the exception of Joey Archer, most of the white fighters of my time have been imports like Nino Benvenuti, or Ingemar Johansson, or flabby, out-of-shape dockworkers looking for paydays, or stiffs who can’t fight. The training camps had peculiar, special atmospheres: paranoid (Muhammad Ali), Spartan (Floyd Patterson), rowdy and boisterous (Torres). They never looked like the training camps in the movies. Quarry’s camp did.

“I’ve handled hundreds of fighters,” Bentham said. “I’ve had champions like Carlos Ortiz, and real good pros like Eddie Cotton. This guy is one of the best I ever had. He’s a real heavyweight, weighs in about 198, and punches like one. He’s mean and nasty when he fights. I like him, I really do.”

When Quarry finished, there were no small speeches thanking the people for coming, in the manner of Patterson, and no banter, in the manner of Muhammad Ali. He walked over to the heavy bag, punched it for three rounds, battered the speed bag for two more rounds, then did situps for two more rounds. Boxing for money was work, and you did what you had to do to get the job done. When it was over, Quarry walked back to the dressing room without signing autographs or handing out photographs. He smiled at no one, and you had to think: this is one mean bastard.

“He’s really a nice kid,” Bentham was saying. “It’s just that he’s changed in the last year or two. He knows what he wants and how to get it. All the rest of it doesn’t matter.”

“That’s right,” said Johnny Flores, who manages Quarry with Quarry’s father Jack. “I’ve known Jerry since he was six years old. He used to come to my gym, this gym I had behind the yard out there in California, and he started right from the beginning, right there. He only weighed 45 pounds, and he fought in the Junior Golden Gloves. By the time he went in the real Golden Gloves, back in ‘65, he already had maybe 300 fights. So he goes to the nationals and knocks out five guys in 18 minutes, and everybody says, ‘Who’s this guy? Where’d he come from?’ But he had been learning all his life.”

“…’If they wanted me to be an animal, then that’s what I would be. A real animal.’ …”

Quarry is one of eight children of Jack and Arwanda Quarry. Jack, the son of an itinerant Irish house-painter, drifted to California from the Texas cotton patches, after living in 30 towns in 16 states. He is a tough hard man, with the letters HARD tattooed on his left hand and LUCK on the right, and he started teaching his sons how to fight very early. “I wanted them to use up their energy,” he once explained, “so they wouldn’t steal.”

Jerry himself lived a childhood right out of The Grapes of Wrath: he attended school in 30 towns from the second to the eleventh grade; in high school alone he spent time in the California towns of El Cerrito, Washington, Porterville and Dominguez before graduating from school in Bellflower. After graduating, he married Mary Kathleen O’Casey, a girl he met while both worked at a Tastee-Freez. He had already developed a talent for bad luck that few athletes can equal. His medical history included nephritis, a ruptured appendix, a broken arm, knuckles that were broken 17 times, a cracked ankle, and a broken back (this happened when he was 16 and he missed a swimming pool he was diving into). He has been hit on the head with a cue stick (there is still a scar where 14 stitches were taken), developed an ulcer (now cured) and cracked a vertebra in his spine while roughhousing with his brother Jimmy in his father’s bar in Norwalk, California.

After turning pro, Quarry acquired other characteristics. From the beginning, he was a good puncher (he has knocked out 19 of his 37 opponents, with two losses and four draws). But there were times when he did not seem to exert himself much. As a counter-puncher depending on his opponents to come to him, he stalled a lot, waiting for the fight to start; if the other guy did not want to fight, there was no fight. His first loss, to veteran Eddie Machen, happened, he said, because he thought Machen was too old and did not train. He fought a draw with Floyd Patterson, but it was tainted because after dropping Patterson he became listless and let the fight get away from him. When he fought Jimmy Ellis for the WBA championship, he spent most of the time leaning on the ropes, while Ellis stared at him. The California fans started booing him, even when he showed up at other fights.

“I was bitter after the Ellis fight,” Quarry told me as we sat in the fighter’s quarters later. “I went into the fight with a cracked fourth vertebra in my back. I couldn’t bend, I could hardly move, but I wanted the fight. It was stupid. But then the hate mail started coming in, all these punks who wouldn’t have the guts to get into a ring, abusing me, telling me how to fight. My back was in a cast for two months after that fight, and I did a lot of thinking. If they wanted me to be an animal, then that’s what I would be. An animal. A real animal.”

“Jerry decided to become more aggressive,” Johnny Flores said. “He was always a counter-puncher, waiting for the other guy to make a mistake. But the customers didn’t like it. So when he came back after they took the cast off, we told him to go out and go after them. And he did.”

Quarry really came back last March 24 when he boxed Buster Mathis before 16,000 fans at the Garden. He had gone through five mediocre opponents in tank towns, and the gamblers apparently did not believe that Quarry had changed much. Mathis had 37 pounds and four inches in height over Quarry and had just scored an impressive win over George Chuvalo. The gamblers made Mathis an 11-to-5 favorite. Quarry laughed. “That big stiff has a streak of mutton in him somewhere,” Quarry said, “and I’m gonna find it early.” He did. The first two punches to Mathis’ huge body seemed to terrorize him, and Quarry went on to batter him brutally over 12 rounds.

All over New York, in the days after the Mathis fight, you began to hear the talk of the White Hope. Of the last eight heavyweight champions, only two have been white (Rocky Marciano and Ingemar Johansson). After the politicians took away Muhammad Ali’s title, two new champions emerged: Jimmy Ellis in 44 states, and Joe Frazier in six states, including New York. The new, aggressive Quarry thinks he can beat both. There has always been a racial and ethnic undertone to boxing matches, with all sorts of resentments and hatreds being fought out theatrically in public; but the big money is in the heavyweights, and for a white heavyweight with an Irish background to come to New York at this point in time was a boxing promoter’s dream.

“I boxed Frazier in the gym about four years ago,” Quarry said later. “It was the Main Street Gym in L.A. in the afternoon. He’s putting out a lot of stuff that he dominated me. That’s a lot of crap. I hit him some good shots, and I discovered that he can’t really punch too good. I know this: I’m going in there and I know I can beat him. You ever feel that way? That there is one guy you just know you can beat? Well, I know I’m gonna beat this guy. And it will be a hell of a fight.”

Quarry was playing solitaire at a big round table, while Flores, Bentham and a friend named Dave Centi played poker. He seemed much looser now that the controlled violence of the workout was over. He had just finished reading the mail, most of it hate mail. “I’ll never fight in California again,” he said. “They’re the worst fans in the world, and the New York fans are the best. I’ll still live out there, but when I win the title, I’m gonna win it for me, and for the few fans who remained loyal to me. I’m not gonna win it for California. They appreciate Irishmen here. After the Mathis fight, that little squirt Mando Ramus (the lightweight champion) said ‘It looks to me like he still doesn’t like to fight.’ That little squirt, he doesn’t want another champion out there to share the limelight. I went to two fight shows after the Mathis fight, and was introduced. I didn’t hear one cheer. The hell with them.”

“… ‘I went to two fights after the Mathis fight and was introduced. I didn’t hear one cheer. The hell with them.’ …”

Centi turned on the TV and Somebody Up There Likes Me started playing, with Paul Newman playing Rocky Graziano. Quarry kept playing solitaire, looking up from time to time at the film. He said he lives now in a $45,000 house in La Palma on the coast south of L.A., he has put money into two apartment houses, and has about $200,000 in stocks and mutual funds. He would like to try acting after he retires, “but I just live my life from day to day. Whatever’s gonna happen, will happen. That’s the way I am.”

Finally Paul Newman started fighting Tony Zale for the middleweight championship. Teddy Bentham said that Newman had a pretty good uppercut. Centi started to cheer. Flores said he would like to sign up the scriptwriter. There was a final scene where Graziano comes back to the Lower East Side for a victory parade, with thousands of people out in the streets. Quarry watched it intently.

“They really did have a parade for Graziano,” someone said.

“If I win the title,” Quarry said, “they’ll come around to my house and throw garbage on my door.”

We went outside and stood in the darkening evening.

“What nobody understands about this business,” Quarry was saying, “is that it’s not a game. It’s a job. It’s got nothing to do with what you like, only with what you gotta do. You go out there and do a job of work. When I started, I was really a kid. Now I’m a man, I’m mature, I know what I want, and I’m gonna get it.”

He watched some people walking slowly by, looking at him strangely. He didn’t seem to care what they thought of him. In a few weeks he was going to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world, and if he won, this Okie’s son would probably become a millionaire. He started off past the gawkers, as if he could see all the way to Eighth Avenue and 33rd Street, into the ring of the Garden, where someone was holding his hand aloft and pronouncing him a champion. He seemed a tough and bitter young man, who wanted the cheers of strangers, but who had taught himself not to care whether he got them or not.

Someone asked him whether he though of himself as a Great White Hope.

“Screw White Hopes,” he said. “I’m a fighter.”