After the legendary Boston Garden closed in 1995, auctioneers looking for salvageable memorabilia found highly valuable pieces in out-of-the-way places: An abandoned darkroom was inches deep in vintage photos of Hall of Famers, while the arena’s original blueprints were stashed in a wooden trunk near the roof. It seems safe to say that no such hidden gems will be stumbled upon when Yankee Stadium closes after this season. There’s an entire company that’s been hunting down and selling vintage Yankees memorabilia at astronomical prices for years. Rather, the Yankees will be selling their stadium’s leftovers. If the team is so inclined, one prospective auctioneer says, it could get a couple hundred dollars for the trash cans.

There are a few items that won’t be considered for sale. Thurman Munson’s locker—unused since the team captain’s mid-season death in 1979—will be moved to the new ballpark. There’s been talk of leaving the dugouts in the parkland that will replace the stadium. And the mythic bronze sculptures beyond the left-center-field wall are too much of a fan attraction to ever get rid of. Besides that … “It sounds like everything is going,” says Phil Castinetti, the owner of a memorabilia store near Boston called Sportsworld.

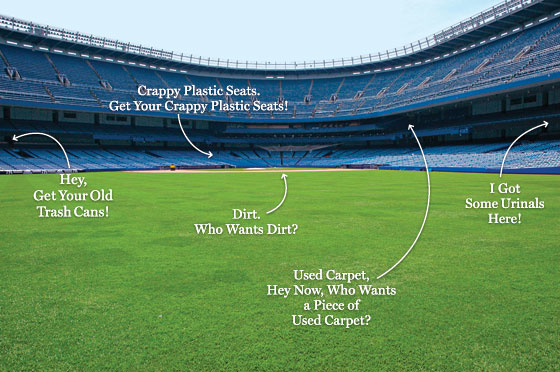

The exact details of the sell-off aren’t settled yet. The stadium might close within weeks of the Yankees’ final game, or as late as March 1 of next year to allow for concerts and other events. The City of New York owns the park and has to be financially mollified before it allows the gutting to go forward. The auctioneers have yet to be selected—there are a number of suitors, although some sports-memorabilia dealers consider it beneath them to sell items like upper-deck seats and urinals.

Their loss. This will be a quantity-over-quality sale for Yankee diehards with money to burn, and that’s a vast pool of buyers. Consider that retired former Port Authority executive Andy Fogel paid $1,200 for the home plate used at Shea Stadium on Opening Day 2008 (Shea also closes this year). The Mets are a team with one of the largest, most devoted, and most affluent fan bases in the sport—and by comparison, when the Yankees sold their ’08 Opening Day home plate, it went for eight times as much. In the end, observers say, the coming bonanza will turn literal junk into as much as $50 million.

The Yankees themselves have helped to create much of the sports-memorabilia market as we know it today, though the team didn’t catch on quite as quickly as they could have. Before the team began gut-renovating the stadium in 1973, it sold some memorabilia informally. Sportswriter Bert Sugar (now 72 years old), who was then working as an advertising executive on the Yankees account, paid a small amount—which he won’t disclose, but describes alternately as “embarrassingly low,” “chump change,” and “not much more expensive than a bread box”—to make off with everything he could fit into a truck. The haul included Casey Stengel’s shower door (interesting to Sugar because “he must have peed on it”) and Babe Ruth’s underwear, located inside a bat bag (“It looked like a cow udder”).

Sugar sold much of his stash over the years, though for prices far below today’s market value. The current state of memorabilia sales makes him apoplectic. “There’s no rationale—it’s like the art market,” he says. “When Charlie Sheen [one of several celebs with big sporting collections] decides he wants something … I started it and then got out of the way before it ran me over. I lost out on $5 million, but what the fuck?”

The concept of memorabilia is not new, of course (baseball cards are a century-old business), but it wasn’t until relatively recently that businesses began cashing in on adult fans’ affection toward teams and players to sell them things other than tickets. Given that the Yankees have exploited new revenue sources more than any other team, it’s appropriate that Joe DiMaggio was the one who really kick-started memorabilia-collecting’s escalation to a mass-production affair when his signed baseball cards, bats, and balls started showing up on the QVC network about twenty years ago. Sales heated up throughout the nineties; the field’s arrival as a big-money game was announced most forcefully when Sotheby’s auctioned the collection of a Yankees minority owner named Barry Halper for a total of $21.8 million in 1999. (Billy Crystal bought a Mickey Mantle glove for $239,000.) But more relevant to the present situation was the ascendancy of PR guru Brandon Steiner’s memorabilia company, Steiner Sports. Steiner realized that there was a lot of demand for sports-world artifacts among people who couldn’t pay $200,000 for a glove, so they solved the supply problem by turning nearly everything sports-related into an artifact. If it was used in or around a game, Steiner would sell it. The memorabilia industry as a whole does more than a billion dollars in sales per year. The Westchester-based Steiner company is now a $50 million slice of the global marketing firm Omnicom Group (2007 total revenues of $12.7 billion).

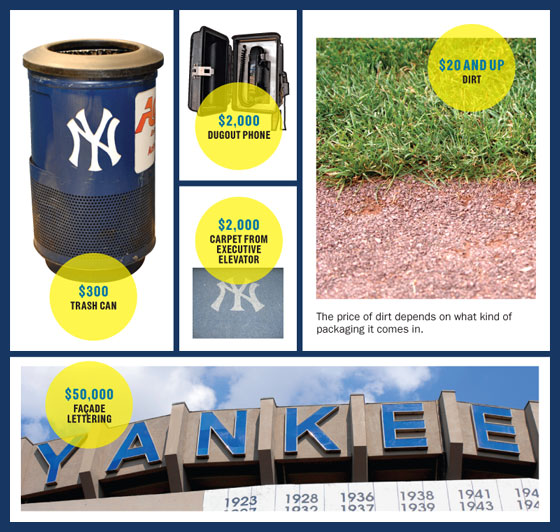

The Bronx Bombers are Steiner’s oldest and best partners—Steiner has had an exclusive license to sell “game used” Yanks merchandise since 2004. Mounted pinches of Yankee Stadium infield dirt sell for between $20 and $149. Some “collages,” as they are known, include a photo of the park or a player. The $59.99 Derek Jeter version is Steiner Sports’ most popular item. “People joke about that, but we’ve heard it so much we are immune,” says Steiner executive vice-president Sean Mahoney. “The reason it’s so popular is it’s affordable.”

In fact, the dirt collages are in greater demand than ever. Sales were up five times this past April over last year, thanks in large part to a new time-line edition commemorating Yankee Stadium’s farewell season. Steiner expects its total sales to rise 20 percent this year, and that projection is partly based on the higher final-season prices they’ll be getting for the balls, bats, jerseys, and dirt they would have sold anyway. (Memorabilia prices, one collector who’s also a Goldman Sachs executive director explains, are relatively impervious to economic downturns: Items with sentimental value are the last things to get sold—when people need cash, they get rid of securities first, keeping the Mickey Mantle–glove market relatively unflooded.) Whereas in past seasons game-used balls could be had for as low as $129, this year they typically go for $300 to $500. The company already has plans for what it is billing as “The Greatest Yankee Auction Ever.” The event will be held online in November and will feature a thousand lots made up of things like collections containing one baseball from every home game this season, which Steiner expects to sell for between $20,000 and $30,000.

Before the team began gut-renovating the stadium in 1973, it sold some memorabilia informally. Sportswriter Bert Sugar paid a small amount to make off with everything he could fit into a truck.

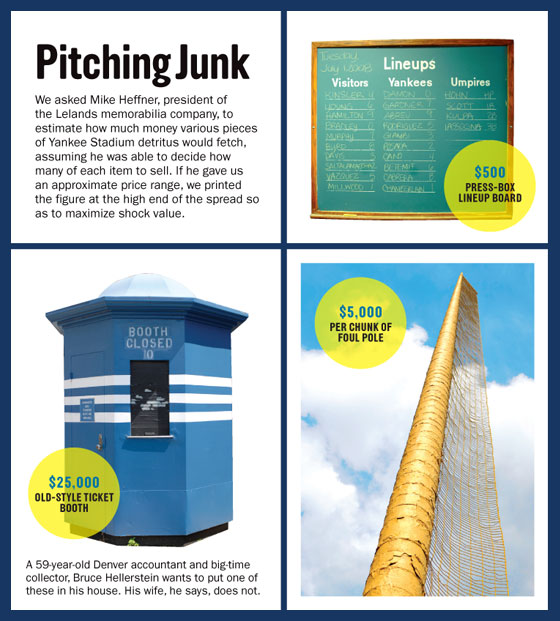

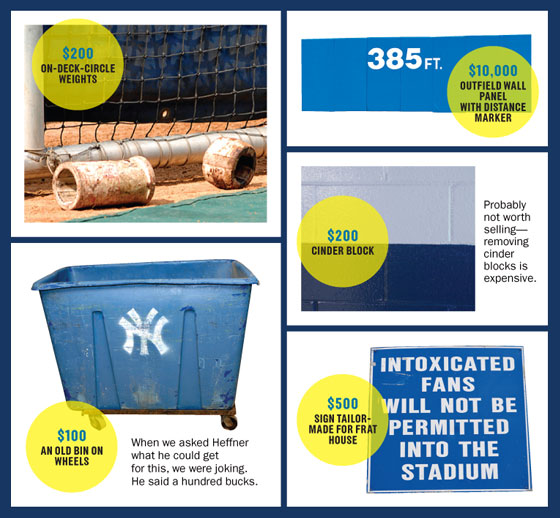

The real payday will come from the liquidation of the stadium’s hardware. Industry pros and collectors guess that even the most quotidian items—bricks, on-deck batters’ weights, fungo bats, etc.—will sell for hundreds of dollars. Anything that distinguishes itself will go for much more. Mike Heffner, president of the memorabilia company Lelands (which ran the scavenging of the Boston Garden), guesses he could sell the dugout phones for $2,000, A-Rod’s locker for $50,000, the YANKEE STADIUM façade lettering for $50,000 as well, and the white frieze atop the scoreboard for $250,000. (Heffner points out that the uniqueness and grandeur of an item can be tempered by the logistical inconvenience of owning it, which is why he thinks a small, self-enclosed, relatively easy-to-display locker would go for as much as the iconic façade lettering, for which “you’d need an 80,000-square-foot house.”)

Heffner might get his chance. The City of New York owns the seats, dugouts, flagpoles, and other “permanent” structures at both Yankee and Shea stadia. With so much money to be made, concerns besides Steiner have been angling for a piece of the action. A multiparty negotiation between the city, the teams, Steiner, and other vendors is ongoing. In the past, the city has been criticized for the favorable terms on which it rents out the stadia to the teams—the Mets paid $550,000 a year in Shea rent for 30 straight years at one point; in fiscal 2007, the Parks Department collected more in Yankee Stadium parking fees ($3 million) than it did in rent ($2.3 million). More recently, the city has been attacked by watchdog groups for giving the teams big breaks on the new ballparks—one critic estimated the municipal government’s contribution to the new Yankee Stadium at over $415 million (the city says it’s $280 million). Asked roughly what share of the auction loot the city would be looking for, New York City Economic Development Corporation president and chief negotiator Seth Pinsky said acidly, “The percentage will be between 0 and 100, and the dollar amount will be above zero.”

The competition among prospective vendors is intense. Take the urinal issue, for example. Heffner is deeply skeptical that the employees of Steiner Sports have enough experience in the area. (He does, oddly enough, from previous stadium sales. It costs $500 to pay “union guys” just to take each one out, he says, so if you flood the market, you can end up losing a lot of money fast.) Bidders are also trying to come up with creative ways to add value before selling. Heffner points out that a seat signed by Derek Jeter will be worth more if its seat number is 2, just because that happens also to be his jersey number. Mitch Adelstein, founder and president of the Florida-based firm Mounted Memories, entered the bidding for some of Shea’s remains. “What’s overlooked is the visitor’s side,” Adelstein says. “Think about who was in those locker rooms—Roberto Clemente, Hank Aaron. If the locker-room bench is the same as the one that was there in 1964, we would cut up the bench into pieces. We might cut them into one-inch-by-one-inch squares, frame them with a picture of Roberto Clemente, and talk about how Clemente was on the National League All-Star team in 1964.”

The lengths to which some sellers are willing to go to create artifacts speaks to one of the problems that auctioneers will face. Shea Stadium, built in 1964, isn’t really that old; Yankee Stadium was entirely renovated in the seventies, which means a lot of the items with the most historical notoriety are already on the market thanks to people like Bert Sugar. Some serious collectors are not particularly enthusiastic about this season’s sale: For them, the Yankee Stadium façade should start with the word new. “I’m not so sure the collectors I know are going to be interested in this stuff,” says Stephen Wong, author of Smithsonian Baseball: Inside the World’s Finest Private Collections. “They’re not really into new things.” Reached by phone in Los Angeles, director and collector Penny Marshall—who owns a seat from the original Yankee Stadium—initially expressed interest in a contemporary companion. She balked when told that one seat could cost $1,000 (which doesn’t necessarily mean that all 55,000 will go immediately for that amount). “That seems high,” she says, “since they’re fucking plastic.”

Prospective auctioneers are confident, however, that Yankee fever will outweigh these concerns. Consider 59-year-old Denver resident Bruce Hellerstein—a successful tax accountant who painted his basement to look like Yankee Stadium, which he considers the greatest sports arena “going all the way back to the Roman Colosseum.” Hellerstein wants an original ticket booth, the prospect of owning which he described as “like, totally awesome” when we spoke. (“My wife just laughed” when he mentioned the booth to her, he said, “so on the record, I don’t want it.”) Many players have already asked for their own keepsakes. Steiner’s Mahoney says Andy Pettitte requested outfield fence paneling. (The company divides the paneling into pairs—with, say, the “3” and “1” of the distance demarcation on one strip and the “8” on another—to get the most money possible out of it.) Mariano Rivera will probably want a pitching rubber. Kevin Millar, the Orioles first baseman who played with Boston during the 2003 and 2004 seasons that included some of contemporary Yankee Stadium’s greatest games, advocates a more direct approach. “I’m going to take something,” he says. “I might take a chair, a hanger, or some shit. Something’s going to be taken.”

If there is any doubt that maybe, possibly, the harvesting of Yankee Stadium will not yield huge dividends, it is at the Steiner Sports booths that all those doubts go to die. An hour before the first pitch at a recent game, the stadium sale’s target demographic had already gathered in bunches around a booth on the left-field line in the lower level. A signed, framed Joba Chamberlain photo was on sale for $450. One sign touted a raffle: WIN A GAME-USED FINAL SEASON DIRT COLLAGE! A wiry, weathered fan in an old Yankees sweatshirt bent down to inspect a plaque in the case. Along with a photo of A-Rod, it featured a sprinkle of dirt about the size of a tin of Carmex lip gloss.

“How much?” he asked the youth at the counter.

“Seventy-five.”

“Not bad.”