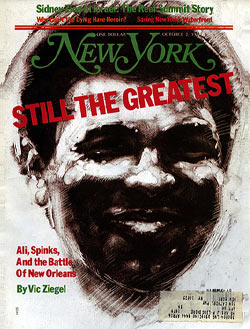

From the October 2, 1978 issue of New York Magazine.

Do you know if I beat him the first time I wouldn’t of got no credit for it. He only had seven fights … the kid was nothing… . So I’m glad he won. It’s a perfect scene. You couldn’t write a better movie than this. This is it. Just what I need. Competition. Fighting odds. Can the old champ regain his title for a third time? Think of it. A third time. Do or die. And you know what makes me laugh? He’s the same guy. Only difference is he got eight fights now.

—Muhammad Ali on Leon Spinks before their championship fight

The copy of Money magazine offered to Leon Spinks during his flight to New Orleans was full of splendid suggestions for a new career. Soccer coach, that was something the heavyweight champion might want to think about. Nowhere is it written that soccer coaches have to run through strange cities at five in the morning. Or spend great hunks of each day inside expensive hotel rooms that offer baskets of apples and Gouda instead of X-rated film selections. And there aren’t small armies of people telling the cover-boy soccer coach to kick this, do that, no this, no, no, no … armies that depend on the heavyweight champion to provide their per diem expenses.

The magazine went unread, of course. Leon Spinks was in Louisiana to defend his title against Muhammad Ali, a 36-year-old body with the staying power of Tutankhamen. Ali was the favorite. Ali was the attraction—the once, twice, and future champion. Leon Spinks? Come on. Just another name on an expired driver’s license.

“Did you hear what Spinks did when he came off the plane?” The lawyer is talking to a sportswriter after the fight. The party is at the Windsor Suite of the New Orleans Hilton. Sportswriters are badly outnumbered by designer suits. Worse yet, the lawyers had heard all the best available fiction.

“Spinks gets off the plane and he does an interview. Everything’s cool. No problems. And then they hustle him into the sheriff’s private car to drive him to the hotel. The first thing he does—this is in the sheriff’s car, right?—the first thing he does is take out a joint and light up.”

Leon Spinks was taking a terrible beating in this Windsor Suite soiree. Bob Arum, the promoter who brought the fighters together and sold them to television for $5 million, controlled the rights to Spinks’s first six title defenses. Poof, all gone. But this was no time to mourn. Another of Arum’s champions, Danny “Little Red” Lopez, a rock-fisted 126-pounder, had survived a first-round knockdown to render his opponent unconscious one round later. And Arum had an unexpected bonanza in Mike Rossman, the light-heavyweight son of an Italian father and Jewish mother who fights with the Star of David on his trunks and shoes. (If you’ve got it—even when it’s your mother’s maiden name—you flaunt it.) Rossman, 22 years old, became champion after stopping Victor Galindez, the longtime titleholder.

Rossman and Lopez—the promoter was delighted with both of them. Those were the names he repeated. Leon Spinks? “What a waste of talent,” Arum said. “He was drunk every night for the two weeks before the fight.”

Muhammad Ali, on the other hand, was taking care of business. He so desperately wanted to become the first boxer to win the heavyweight title three times that he decided on a strategy he had previously abandoned: He trained. When he stripped to the waist for the first time in New Orleans, there was no sign of the jelly doughnut above his belt. “I want you to know I’m real serious for this fight,” Ali said. “Put your money on me. I cannot get no better.”

He rented a home in West Lakeside, a New Orleans suburb, and rarely visited the hotel’s fight headquarters. “We’re getting police protection like I never seen,” said Gene Kilroy, who calls himself Ali’s business manager. “About every five minutes a cop car drives down our street real slow. They want what everybody else wants … see if they can spot Ali, get an autograph.”

The business manager had an easier time of it for this fight. Ali’s entourage was issued dated vouchers, $25 a day, and there were no newcomers with expensive habits. “Before we went to Los Angeles for the second Norton fight,” Kilroy remembers, “Ali met a guy in New York and flew him out to the coast. He gives the guy a room in the hotel. Then the guy decides to throw a party to tell everybody Ali’s his friend. Only the room ain’t big enough so he gets the hotel to open up the adjoining room for the party. And he sends flowers to Ali. Later I’m going over the bills for the fight, and there’s one bill for the flowers and another for the party, $3,600.

” ‘Lookit this crap,’ I tell Ali, your new friend signed your name for $3,600.’ But Ali says, ‘He’s doing what he thinks is right and who’s to say he’s wrong?’ So we ended up paying for it. Stuff like that went on all the time.”

This time, the hangers-on were hooking into Spinks, the St. Louis ghetto kid punching for $3.75 million. A few minutes past midnight, three days before he returned Ali’s title, there was a crush of people near the Hilton’s front door. On the steps leading to the bar stood Leon Spinks, smiling his jack-o’-lantern smile, surrounded by members of his cabinet. The people with Spinks waited for a sign. Hotel guests at the foot of the stairs stared up at Spinks. One of them asked if he could take a picture. Leon smiled in his direction. Another wondered if he might pose with Leon and he was told to mount the steps. Leaving a wife and camera behind, the man moved to Spinks’s side. The flashbulb missed and the man urged his wife to try again. The second time was fine. He half trotted away from Spinks.

“Who are all those guys with him?” The question came from a young man in a Tulane sweatshirt.

“His entourage,” I answered.

“What does he do?” He pointed in the obvious direction—at Mr. T., shaved head, dark glasses, one earring with a gold half-moon and star.

“The bodyguard.”

“Where’s the guy who tells him to go to bed?”

Spinks didn’t fill that opening.

“He’s just a softhearted kid,” says Butch Lewis, “but he gets caught with his pants down a lot.” Butch was the vice-president of Top Rank, Arum’s organization, who helped to deliver the Spinks brothers, Olympic champions, to Arum.

“Leon’s always looking for somebody to say he doesn’t have to do something. And the people around him want to keep a smile on his face. They’re afraid of him when he gets to growling. He’s got a lot of tap dancers around him all screaming, ‘Yeah, champ.’ He says, ‘I think I’ll go out tonight; it won’t hurt me.’ There they are, ‘Yeah, champ; anything you say, champ.’ He’s surrounded by people who don’t know anything about boxing. They’re scufflers.”

Incidentally, Butch’s last favor for Arum was finding the Louisiana backers who paid Top Rank $3 million to stage the fight in the Superdome. After the fight, Arum fired Butch.

Dr. Ferdie Pacheco worked in Ali’s corner all the way back to when the name on the robe was Cassius Clay. The urbane physician’s recently published Fight Doctor included two or three teasing sentences about Ali’s sex life. Three too many. His fifteen-year association with Ali ended before the first fight with Spinks.

“After the Norton fight in Yankee Stadium [September 1976] I told him not to fight anymore, to walk out. What I’m saying to him he doesn’t want to hear right now.” Pacheco’s in New Orleans to broadcast the fight by satellite. He hates what he sees.

“What can Ali do but further deteriorate his legend? With each beating he takes, he gets less able to take a beating. I hope to hell I’m wrong, but if he could get lucky and beat Spinks it would be the unluckiest thing that ever happened to him. He would go on to so-called easy fights. But there are no easy fights for this guy. The body doesn’t know whether you win or lose, and his body is getting beaten up on the way to the fight.”

When Ali trains he often lets sparring partners beat on him. He calls it building resistance to punches.

“That’s not what nature intended,” Pacheco insists. “You don’t toughen up the brains and kidney by letting them get hit a lot. It’s not the same as putting calluses on hands. Cosmetically he looks the same, but his reflexes are not there. His legs used to get him out of trouble, nobody could hit him. Now everybody can hit him. And now he’s slurring his words. Which is the sine qua non of brain damage. It hurts me to see the way he is.”

The 48 hours before the fight take too long. Another visit to Bourbon Street was out of the question. On the first, a pilgrimage was made to Preservation Hall, where a dollar thrown into a basket is the only charge for the privilege of listening to jazz’s founding fathers. Percy Humphrey, a trumpet player shaped like a walrus, opened a set by lifting himself off his chair and grumping, “No smoking, no taping.” The band spent the next twenty minutes giving new evidence of the decline of the American dollar’s buying power.

But the one good deed for the entire stay was performed during this second Bourbon Street foray. Jose Torres, the former light-heavyweight champion who now punches a typewriter, was seriously considering the purchase of a T-shirt that read, “I Choked Linda Lovelace.” Torres was adamant, and giggling too. His friends argued that the T-shirt wouldn’t travel well and Torres finally agreed, although he muttered something about only getting to go around once in this life.

So you see, the 48 hours before the fight were taking longer than usual. Just in time, Emile Bruneau turned up. Bruneau, chairman of the Louisiana Boxing Commission, is a sensational churl with a low tolerance for the northern accent. Bruneau is the chap who, as an officer of the World Boxing Association, had a great deal to do with taking away Ali’s title and sending the champ into his three-year exile. When a reporter asked Bruneau if he was responsible for that act, the chairman said, “The committee stripped him of his title.” And how did you vote on that committee? “None of your business,” Bruneau snapped. “That’s eight, nine years ago. You wanna dig up skeletons, go to the graveyard.”

The reporters were delighted. And when somebody remembered the mysterious brown bottle that Spinks had emptied in the first fight—suspected by some to contain an illegal energy booster— there was a new line of questioning. What would the fighters be allowed to carry into the ring this time? “A bucket with water and water only,” Bruneau fumed. “How the hell do I know what they’re carrying into the ring? I’m not Houdini.”

After Mr. Bruneau, the rest was easy. The Superdome, for instance, described in the brochure this way: “Over the streets named Bourbon and Basin, St. Charles and Desire; over the river that’s still sung about; over sad jazz erupting into laughter; over the glory of cuisine by masters, the Superdome rises. The Superdome is more than a building or a stadium or a hall. It is the enshrinement of Louisiana’s belief in itself and a budding, exhilarating, moving certainty that tomorrow can be now.”

The certainty was easier to glimpse from the $200 seats on the floor. The near trampling of Muhammad Ali as his entourage, driven wild by the $25-a-day starvation diet, flooded the aisle and carried their hero toward the ring. Spinks’s inner circle wore red warm-up suits; his second rank was in green. And the angriest man in the young champion’s corner was George Benton, the master trainer who devised many of the tactics that carried Spinks to the title.

On this night, Benton was reduced to a part-time adviser. He was to offer his opinion every third round, alternating with Spinks’s brother Michael and Sam Solomon, the chief trainer. The arrangement bothered Benton.

“It would be a damn shame if he loses,” Benton said, “and the only way he can lose it is on general bullshit. We don’t need five guys in the corner, filibustering, telling him some dumb s - - t. There are a lot of things around this fellow that he doesn’t need. But he’s a very strong person. He takes care of the business at hand. Look at it this way: If your mamma died one day and the next day you were attacked by a wild dog, you’d stop thinking about your mamma. You’ve heard fighters be asked how they lose a fight, and they say they had too much on their mind. Now how the hell can you have too much on your mind when you’re getting the s - - t kicked out of you?

“Straight up, this kid has no business losing this fight. No business at all. But Ali’s life’s been protected by some mysterious force. I’m always respectful of that. Can it happen again? Sure. You can’t say he ain’t gonna win again.”

The “National Anthem.” Spinks applauds. Ali glares across the ring at his opponent. “You’re not gonna psych him,” says Angelo Dundee, Ali’s trainer. “I don’t think this guy’s bothered by that. I think he’s a happy warrior.” The ring announcer introduces Ali. Spinks beats his gloves together.

When Ali swept through the early rounds—landing a few, grabbing, nullifying Spinks’s clumsy charges, landing, grabbing—George Benton’s worst fears were realized. After the fourth round, unable to take his place in front of Spinks, he turned away from the ring and cursed. “Ten guys in front of me,” he said. He walked off, ignoring the shouts of the green warm-up suits: “George, George, no, no…”

The fight dragged on. Nothing changed. “Get tough,” red and green suits begged Leon. “Bite down … smoke … be loose … use your gusto … do the hustle… .” The decision for Ali was mercifully unanimous.

And later, when they asked Spinks why he had been so ineffective, he said, as Benton was afraid he would, “My mind wasn’t on the fight.”

Ali thought he might fight again in six or eight months. Then again, he might retire. He’ll let us know. Back at the Hilton bar, Alvin Cash was demonstrating the “disco hat,” a visored cap with a row of battery-operated bulbs. “I’m just doing this as a favor for a friend,” Cash was saying. “I’m an entertainer.” He passed along a press release. “I was in The Buddy Holly Story. I’ll probably be in Muhammad Ali’s next movie, acting and singing. I’ll be doing my new song, the ‘Ali Shuffle.’”

The press release identified Muhammad Ali as a “personal friend, supporter and source of inspiration to Alvin Cash for almost 20 years. Mr. Cash recently was featured on the testimonial program ‘A Night with The Greatest’ which was videotaped for later presentation… .”