Chase Buchanan didn’t want to leave home. His mother knew that. Since he was a kid, Chase has always tried to prove that he could do what they all said he couldn’t: make it as a top pro, and do it coming from a gloomy, chilly sprawltopia like Columbus, Ohio. He never wanted to become, his mother says, “one of those academy kids,” the ones with rich daddies and Florida condos and perma sock tans. Chase was cocky and stubborn, and he could get away with it while he was winning. But now he was 16, the competition was older, the serves were faster and tougher to return, and he was losing.

He lost in El Paso. He lost in College Station. He lost in Philly. He had, his coach from childhood said, “a stall-out moment.” To help, the coach bought him a medallion and had it mounted on a silver chain so Chase could wear it around his neck. The medallion had an inscription. It read, WHO DO I WANT TO BE IN THIS EXACT MOMENT? Then the answer: IN THIS MOMENT LIES MY ATTITUDE.

Chase wore the medallion. He still lost.

Then he got hurt. He injured his back. He lost momentum. The culmination of his season was last year at Flushing Meadows, in Queens, at the U.S. Open Junior Championships, an annual event for teenagers that starts in early September and takes place on courts far away from the action of the pros and the spotlight of the press. At the Open, Chase’s game was so off that he didn’t even qualify.

As a boy, Chase was the top junior player in America. Now he was on the verge of cracking up into a cautionary tale. That’s why he and his mother knew he had to finally leave Ohio. But where to?

He had free rides to all the major factories. At the top of the list was Nick Bollettieri’s champion-producing mill in Bradenton, on the west coast of Florida, which is owned by the talent behemoth IMG. This is where household names like Venus and Serena and Maria Sharapova all came as kids, and non-phenoms pay as much as $85,000 a year for room and board. Bollettieri is the largest tennis academy in the country (with 310 juniors from 70 countries, as well as over 50 courts), and the diversity of talent it can host is why so many coaches consider it the best. At Bollettieri, there is always someone around who can beat you, and that’s how great players get better.

Saddlebrook, the resort near Tampa, also wanted him. Saddlebrook is where top Americans James Blake and Mardy Fish train. There are about 100 juniors in its program, with 60 boarders; tennis tuition runs about $55,000 a year.

But Chase wasn’t interested in Bollettieri or Saddlebrook. They were “both big spreads,” he says. Too big for him. He worried about sharing the court with too many kids, and the coaching. He also worried about the potential cost. He didn’t want to make that decision yet. He wanted something smaller, less corporate, more boutique. So he decided to enroll himself in an experiment.

The name on the brochure sounds like a performance-enhancing vitamin drink: Elite Player Development. The force behind the program was a new player in the academy business, the United States Tennis Association, the entity charged with the mission of promoting tennis throughout the country. The USTA does everything from building new courts and organizing night leagues to running tournaments (including the U.S. Open) and developing generations of up-and-coming juniors and pros. But this last department has proven to be a critical problem in recent years. The last American to win a Grand Slam was Andy Roddick, who won the U.S. Open five years ago. In the women’s bracket, despite the continuing dominance of the aging Williams sisters, the top ten is owned by the Eastern-bloc invasion of Ivanovic, Jankovic, Kuznetsova, Safina. And despite epic performances from Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer, national television ratings for tennis matches have remained stagnant. The USTA has been trying to reverse those numbers and figure out a way to revive the domestic tennis economy.

One of its solutions is to find a new symbol to inspire younger players, a PR-friendly hero who can win the big points in big matches and has a good story to tell. But it hasn’t been easy finding the Next Great American Tennis Star. So now they have a new strategy. They plan to spend as much as $100 million over ten years to create one.

“We studied it,” says USTA CEO Arlen Kantarian. “We found that if two Americans play against each other, or if one American is playing, the ratings jump. People are looking for an American champion to root for.”

This is the pitch. Kantarian is sitting in his USTA office, just down the hallway from Center Court at the U.S. Open. He talks as any pitchman might, with talking points and first names. “So you see,” he says, “the Open is not only a tennis tournament. It’s a spectacle.”

Kantarian is not a tennis guy. He’s a marketing whiz. Before he took over the USTA eight years ago, he worked as an executive at Pepsi and then at NFL Properties. After the NFL, he ran entertainment and marketing for Radio City Productions, where, among other things, he produced Super Bowl halftime shows. So far, he’s increased revenues at the Open by 42 percent. (The year before he arrived, revenues were $139 million; last year, they rose to a record $198 million.)

“In the end, you have to have a good story to tell,” he says.

Kantarian is the show-business mind behind the most visible changes at the Open in recent years. As a kid, Kantarian grew up near here, in Forest Hills, and he has sought to rescue the sport from “insiders” who kept it “inaccessible.” For starters, he dropped the price of nosebleed seats. Against the players’ wishes, he also installed two Jumbotron television screens, which are mounted high in the stands so nosebleed-ticket holders can actually see what’s happening miles below. He infuriated some players even further by implementing an instant-replay system, now a fan favorite. And to allow spectators to follow the fast-paced rallies even better, Kantarian changed the color of the court from its old grassy green to a blue. He’s also added the “spectacle” part. Now, walking the grounds, you can hear live bands and see nice flowers and eat “the most high-end food in sports,” including “flaming ouzo shrimp” and “locally grown arugula.” He’s also amplified his marketing campaign. For instance: The Open doesn’t offer the best tennis in the world; it offers the toughest tennis. He changed it “because this is the toughest city in the world,” he says. “You have to fight everything, the players, the crowds, the traffic.”

“It’s about celebrating what’s New York about New York,” he says.

“Of course there’s a lot of pressure,” says a coach. “We’re trying to find the next Andy Roddick. We’re trying to find the next James Blake.”

But the story lacked leading men and women: a new generation of American players. So early last year, Kantarian budgeted an initial $10 million to build the USTA’s own tennis factory in South Florida. At this stage, it’s far from a science. The idea is to create a place for Americans only, make it free for everybody, and keep it small and competitive, so the kids have to win their matches to stay there. To run it, Kantarian recently hired Patrick McEnroe. “There’s really no secret in how to create tennis champions,” McEnroe says. “It’s actually very simple. You have to take talent and surround it with talent.”

Chase arrived in November. He flew to Fort Lauderdale, and his coach picked him up and drove north, to Boca Raton. The USTA’s academy is located across the street from a golf course and surrounded by gated communities with flowery names like the Sanctuary and Le Lac.

Chase was taken to the dorm. He put his bags down and looked around. “Everything just had this newness,” he says. The wood from his bunk smelled of fresh carpentry. His desk smelled like varnish. He looked in the bathroom, checked the toilet, and inspected the shower. “All new,” he says. “It was kind of weird.”

In the dorm, Chase met his roommate and the other eight boys down the hall. On the other side of the hall, there were ten girls. All were here for the first time, and all their stories were different.

Chase’s mother, Melissa, was a beauty queen. In high school, she swam and played singles tennis. In college, she was Miss Ohio, and competed in the Miss America pageant. She came in second, and used the proceeds to help put herself through college. Chase’s father, Todd, was a magician. He was always on the road, doing his illusions on cruise ships or at corporate retreats. Often Melissa would perform onstage with him, dressed in a slinky sequined leotard. Chase was part of the act, too. His father did one illusion where he sat on a stool in the center of the stage and told the audience all about what it was like to be a young kid and not bear the burdens of adulthood, and as he was waxing nostalgic—voilà!—he vanished. There, sitting in his place, was young Chase.

“It was spooky,” his mother says.

Then Chase started playing tennis. At 7, he was so good he was offered a full scholarship to Bollettieri. Seven was too young to go away, his mother told him. So he and his mother fashioned their own routine outside of Columbus, getting up at 5:30 a.m. to hit the ball before school.

At 8, Chase began to beat his mother. At 9, he began to win tournaments around the Midwest. By 10, he was training with college kids, and his mother put 40,000 miles on their minivan driving him around. He received his first racquet sponsorship at 11. At 12, he won the junior nationals and got his first clothing sponsor. He also got noticed.

“He was big, he was fast, and he could really hit the big ball,” says Rodney Harmon, head of men’s player development for the USTA.

At 13, after winning Les Petits As, the legendary juniors tournament in France, he received his first offer to turn professional. But 13 was too young for Chase to turn pro, his mother told him, and they chose to struggle with the costs of constant flying, hotel rooms, homeschooling, and a private coach.

That same year, he won the nationals again, and the USTA offered him financial grants to defray his expenses. Now he had two coaches: Al Matthews, and the USTA’s Dave DiLucia. With Matthews, he traveled in the States, and at night, in hotel rooms, Matthews read to him from a book of quotes and applied the heady intellect of Aristotle and Thoreau to Chase’s tennis game. With DiLucia, Chase kept a journal of his matches and traveled throughout Europe and began to prepare himself in earnest for the pro tour.

Then Chase turned 15, and the USTA wanted him to jump ahead to compete in the under-18 division. This created a rift between his coaches. “My philosophy is that you have to conquer one thing before you conquer the next,” Matthews says. “You can’t skip steps.”

The other view, espoused by DiLucia and the USTA coaching staff, is that raw talent needs to be challenged and tested. Chase’s mother felt the USTA was trying to develop her boy too fast, though the USTA finally won the argument. “The USTA, in desperation, pushed a lot of these young players ahead in a hurry,” she says. “Agassi was retiring and Sampras had retired, and it was like, ‘Those guys are all gone. Now we’ve got to do something.’ ”

Hence, the academy. “We were getting blamed for not producing any champions, so we decided to do something about it,” says Jane Brown, the USTA’s president, who adds that cuts were made “across the board” to come up with the academy’s annual funding. “We’ve run out of material,” echoes Nick Bollettieri. “We had a very good eighties and nineties, but look around: the Samprases, Couriers, Todd Martins, and Agassis are all gone.”

Ironically, this Silent Generation began, some tennis people say, when the USTA first began its player-development program, in 1988. One reform the American tennis czars sought to make then was eliminating rankings for all kids under the age of 12. The goal was to replace preteen cutthroat competition with a genuine love for the game. “In hindsight, we made a huge tactical mistake,” says Kevin O’Connor, who runs Saddlebrook. “Our kids are now at least two years, and a couple hundred matches, behind everyone else in the world.”

So now everyone wants to restock the pool of American tennis talent, and the debate is over how this should be done. “There are multiple schools of thought,” says Nick Saviano, a former USTA coach who runs a private academy in South Florida. “One school is that the USTA should be a part of the development process. And the other schools are that they shouldn’t be involved in the process and that it should be left up to the free-enterprise system.” Saviano belongs to the latter school. His point is one of global economics: In order to create the Next Great One, the USTA must concentrate on what America does well, which means keeping the focus on this country’s traditional tennis ethos—independence and innovation.

To others, what worked before is just not good enough. “We’re competing now with the whole rest of the world, and the rest of the world are hungry mothers!” says Bollettieri, who considers himself a partner of the USTA’s academy, not a competitor. But is spending about $10 million a year to push two dozen kids (at roughly $416,667 a head) the best way to go about it? “I’m skeptical of its cost-to-benefit ratio,” says Colette Lewis, who’s been following junior tennis for the past three decades and now runs a blog, ZooTennis.com. “With all the intangibles involved, it’s too risky to devote that much attention and money to a handful of young players.” The gamble is not lost on Kantarian. “Any time you spend money, it’s always, Could we spend it better?” Kantarian had a choice: “Do we spend it on racquets and give them out for free? Do we build more courts? Or do we try to do something different?” So far, he’s tried the first two. With Elite Player Development, he says, “We think it’s worth a try.”

Chase’s decision to enter the USTA’s academy ultimately came down to his coaches. He wanted to keep Al Matthews, his old coach from Ohio, and he worried that coaches at the private academies would try to reprogram him their way. And Dave DiLucia, his USTA coach, wasn’t a threat. “Al and I have a great working relationship with Chase,” DiLucia says. “When I’m with him, I call Al and tell him how he’s playing.” And vice versa.

Now “an academy kid,” Chase, 16, had to make adjustments. His interest, he says, was “girls,” but girlfriends on campus were against the academy’s rules. So many rules! No smoking of any substances, tobacco or otherwise; no drinking of alcoholic beverages; no romance (including hand-holding, smooching, or petting of any kind); no posters on walls; no cursing; no leaving the grounds; and on and on.

“It’s a little ridiculous,” Chase says.

Then he read the schedule. Breakfast, served at 6:30 A.M., was mandatory. Then it was back to his room to change into tennis clothes so he could be on the court by 7:45 to stretch, warm up, then play for two hours under the sun.

It gets hot here. So hot the heat index is measured every day by the academy’s physical therapist so she can attempt to prevent kids from passing out or needing emergency ice baths. Last month, when I visited the academy one morning, the heat index was calculated to be 106.7 degrees. “Eventually, your body begins to acclimate to it,” says Paul Roetert, the academy’s chief administrator.

Today, Roetert was walking around the courts and pointing to this phenom over here (“She came to us from California”) and that one over there (“He came to us from Brooklyn”). He talked about his biggest challenges (dealing with everyone’s parents) and the mission at hand.

“Of course there’s a lot of pressure,” he said. “We’re trying to find the next Andy Roddick. We’re trying to find the next James Blake.”

“We’re competing now with the whole rest of the world,” says Nick Bollettieri, who considers himself a partner of the USTA’s academy, “and the rest of the world are hungry mothers.”

He squinted out into the sun as the kids slid on clay and practiced second serves. With gobs of white sunscreen on their faces, the USTA coaches peered out at their teenage projects from underneath their caps and listened as each shot was grunted out. The grunts were loud at first and then trailed off into a hiss, like a bike tire being relieved of its air.

“Aayyyeeeeeee … eeeyee, eeyee.”

Jay Berger, one coach, was keeping tabs from behind a pair of wraparound shades.

“There’s tremendous benefit to what they’re doing,” Berger said of the grunting. “By exhaling, they control their breathing and get themselves ready for the next shot.”

He looked back at the court.

“AYEEEEEEEEE.”

“Some of it, you know, may be exaggerated. That’s okay.”

Once, Berger was ranked seventh in the world. He’s now the academy’s most ruthless enforcer.

“No question, he’s definitely the toughest,” says Jeremy Efferding, an academy player who just turned 15. He remembers his first days training with Berger. He hit so many balls he began to feel sick. Really sick.

“I threw up,” he says. “All over the court.”

The coach was pissed, Efferding says. “He told me, ‘If you’re playing in a match and you throw up, you throw up on the court. If you’re in practice, you throw up on the side of the court.’ ”

This intense training is necessary for American kids. “In Europe or in Argentina, the kids have no other choice,” Berger says. “They commit early. They know they want to be pros. Here, American kids can use their tennis to be pros, or they can use their tennis to get into Harvard. There are too many choices.”

Bollettieri encourages rough, bare-knuckled play. “That’s how you become good,” he says. “You put 30 hungry bastards in the backcourt, no coaches, and let ’em fight!” Chase’s coach, Dave DiLucia, says the goal is to take all the nervous thinking out of the game. “What we’re trying to do is drill them so hard and so often that when the competition comes, they don’t know anything else,” DiLucia says. That’s why the coaches now supplement their students’ time in Fort Lauderdale with a stint in the actual Marines.

Camp Pendleton is a secure 125,000-acre compound that’s located on a stretch of hilly, coastal terrain in Southern California. It is one of the Department of Defense’s busiest bases, where tens of thousands of soldiers are trained to kill and protect. But the worlds of tennis and the Marines are “identical twins,” Keith Williams, their drill sergeant, told Chase and the other USTA boys when they arrived. “There’s a direct correlation for how tennis players must prepare for competition at the highest levels to what Marines have to do to prepare for combat.” In addition to being a drill sergeant, Williams is also a tennis junkie, and provided the services of the Marine color guard and flyover planes for pro tournaments in Southern California (the “hidden agenda,” he says, is getting to watch matches for free). When USTA coaches told Williams about the academy, he didn’t hesitate to offer up the official boot-camp routine. On day one, the boys were given dog tags and their orders. “We couldn’t talk to each other,” says Jarmere Jenkins, who, like Chase, is among the top 25 junior players in the world. They did push-ups and more push-ups. They learned how to make their beds. They assembled and reassembled M16 rifles and shot the guns in video simulators. They learned martial arts. They spoke in commands. Sir, yes sir! They were deprived of sleep.

“The drill sergeant would come in screaming and wake us up in the middle of the night,” Jenkins says.

They stormed the beachhead. They stormed the mountaintop. Machine-gun fire blazed on in the background.

After camp, Chase was voted by the Marines “most inspirational warrior.” He wasn’t timid. “From the very first minute he totally submitted himself,” Williams says. “He was like, Carve me, make me, I’m in it, whatever it takes.”

But on the court, Chase still lost. He’d blow a point, get emotional about it, crack his racquet, and spiral downward. It almost felt like he wanted to lose.

“He was tanking matches,” says Jenkins. “His greatest weakness is himself.” Chase’s attitude on the court was so poor that DiLucia wrote him a letter this spring. The coach won’t disclose what was said, but it’s fair to suspect that DiLucia doubted Chase’s commitment to being a pro and wondered if he deserved his place in the academy dorms when so many other kids around the country wanted it more.

It’s hard to say if DiLucia’s heart-to-heart is what motivated Chase to win his matches, but he began to dominate. In April, he won the Easter Bowl, a prestigious tournament in California, losing only two sets along the way. In May, he won the Grand Harbor Classic, his first pro tournament victory, in Vero Beach. It was the first time a 16-year-old had competed in the tournament’s fourteen-year history, and it was an impressive win. Chase dropped the first set, rallied back in the second, won the third in a tiebreaker, and committed only one double fault all match. Then he went to Europe—and lost early in three of four tournaments, twice in the first round, once in the second. “I was projecting,” he says.

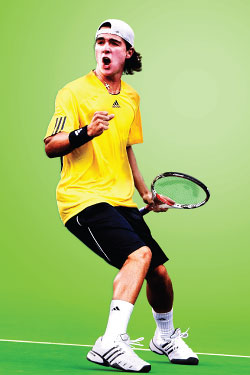

This year’s junior Open tournament begins September 2. Chase is a top seed but hardly the favorite. Under 18, he is ranked seventh in the country, and 21st in the world. He’s behind fellow American Ryan Harrison, 16, of Texas, who is his doubles partner. This month, they won the national tournament in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and earned a wild-card berth to play with the pros. Chase also won a chance to qualify to compete in the men’s singles bracket the weekend of August 19. His challenge is mental. “If I can stay in the moment, I like my chances,” he says.

He won’t be returning to the academy in the fall. McEnroe believes the academy needs younger players, and Chase is on the verge of beginning his pro career. “We know, through research, that kids pick their favorite sport prior to 12 years old, and we want to get great athletes into tennis,” he says. “We’re in this for the long haul, and it’s gonna be a long haul.”