The questioners start out asking what every Knicks fan desperately wants to know: How the hell is Donnie Walsh going to turn this mess around? And could Walsh please erase seven years of embarrassment in about, oh, seven days?

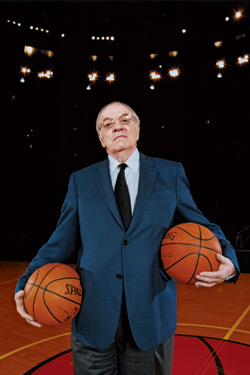

Walsh laughs. He’s back among his people. Walsh’s title is president of basketball operations, but really he was hired in April to be the Knicks’ latest savior, exorcist, and general manager. He is 67 and moves slowly; his hair is slicked back, and he wears a dark-gray suit. He looks like a low-key, pre–John Gotti don. Today Walsh is on a temporary stage constructed amid the seats in a small theater inside Madison Square Garden attending to one of his roles: calming down the Knicks’ angry, sorely abused fan base. It’s a Wednesday night in mid-August. Season-ticket holders have been invited to a Q&A session with the new basketball boss—which is, all by itself, a real breakthrough; Walsh’s immediate predecessors spent much of their tenures avoiding fans, the media, and process-servers.

Walsh’s inquisitors submitted questions in advance by e-mail. John Andariese, a longtime Knicks broadcaster, sits beside Walsh and reads them off cards. Most of the questions stick to the obvious subjects, like how quickly Walsh intends to ship overweight, underhustling forward Zach Randolph out of town. Boos erupt at the mention of Randolph’s name; someone yells, “He’s gotta go!”

“Yeah, ‘He’s gotta go,’ I love that,” Walsh says. His tone is heavy with sarcasm; his voice, a rumbling baritone, silences the crowd like a principal walking into a schoolroom of kids misbehaving for a substitute teacher. “Twenty [points per game] and ten [rebounds per game] and he’s gotta go! I know Zach from when he was in high school. Zach was the best low-post player I ever saw in high school. I say to him, ‘What happened? Where’s your game? You should be an all-star in this league!’ We’ll see.”

Hostile fans Walsh knows how to handle. But “Howard from Riverdale” throws Walsh off stride: “Will you be paying a visit to St. Gabriel’s now that you’re back in town?”

St. Gabriel’s was Walsh’s elementary school in the Bronx. After the nuns were finally done with the boys each day, Walsh would spend hours on the school’s playground, until he was shooting by streetlight. Back then, in the early fifties, the NBA was in its infancy; the real action was in amateur basketball—especially New York City basketball, whose farm system was the highly refined network of Catholic schools. St. Gabriel’s was a lower rung in that ladder, and it was the beginning of Walsh’s life in the game. So when he answers this time, his words are quiet, but the catch in his voice is unmistakable. “Well, I’ve already done that with my brother during the first week I was in town,” he says. “We went up and ate at our favorite deli and went by the church where I was married, the schoolyard where I played.” Then he pauses. “You’re going to get me crying,” he says.

Much of what Donnie Walsh’s new job entails is waiting. He’s inherited a stack of expensive long-term contracts attached to a locker room of mediocre players. It will take him at least three years to completely renovate the Knicks’ roster and turn the team into a title contender. Oh, the team will play better long before 2011, maybe even this season, thanks mostly to the run-and-gun offense installed by new coach Mike D’Antoni. Yet the soul of the Knicks, as an organization, has already been transformed. They are now run by an authentic product of New York’s old-boy basketball culture.

Walsh comes out of New York’s glorious Irish-Italian-Jewish hoops history, a world stretching back to the thirties and populated, in its mid-fifties glory days, by guys named Ziggy and Spook, a world of longshoremen and garmentos and cigarette haze hovering over the hardwood. When the white-haired Andariese, himself a veteran of that scene, asks Walsh to describe the lofty honor of playing in a high-school all-star game at the Garden, he makes sure to clarify that it took place in the legendary “old” Garden, the one on Eighth Avenue that was torn down in 1968.

But a basketball ethos survives from those days, passed down through gym rats and pickup games. Walsh is no nostalgist; he doesn’t subscribe to any rigid theories about offense and defense on the court, and one of his greatest strengths as an NBA executive has been his ability to adapt to the changes in rules and athletes over the years. He’s also a color-blind liberal. But he is fiercely attached to the morality of the game he learned in Bronx CYO halls, at Fordham Prep, and, especially, at the feet of the legendary college coach Frank McGuire. And last year, when lurid headlines described the Knicks’ demise, that city-hoops subculture was quietly maneuvering to bring Walsh home, after 50 years, to try to resurrect New York basketball.

Steaks may be the main attraction at Peter Luger. But there’s an equally rich sense of time to the restaurant, permeating everything from the heavy wooden tables to the thick-sliced-tomato-and-onion appetizer. Donnie Walsh looks slowly around the dining room. He’s been trying to get back here for 40 years. Doesn’t look as if much has changed, he says.

“When I was recruiting for South Carolina, there was an older man who was a friend of Frank McGuire’s—his name was Harry Gotkin, a wonderful guy,” Walsh says. “He used to scout for us, and when I came up to New York, he knew the high-school players, and he’d say, ‘You gotta go see this kid.’ And Harry knew all the restaurants in New York, so he’d bring me to places like this.”

In just a few sentences and references, Walsh has summoned a sprawling, exotic basketball family tree. In the mid-thirties, McGuire was a starter on an overpowering St. John’s team. Anti-Semitism ran high when the team and its Jewish players traveled to rival Catholic schools, and McGuire brawled with opposing players and fans to protect his teammates—one of whom was Dave (Java) Gotkin. When McGuire, as a coach, built dominant college teams at North Carolina and then South Carolina, he did it using what was called an “underground railroad” of recruits from city schools; McGuire’s street agent back in New York—steering players to McGuire purely because he wanted them to get a sound college education—was Java’s older brother, Harry, a jowly garment-district operator.

Among the many great players who found their way into the strange land of the fifties Deep South were Billy Cunningham, from Brooklyn; Larry Brown, from Long Island; and Donnie Walsh—the oldest of five children, born in Manhattan, raised in Riverdale, the son of a dentist for the longshoremen’s union.

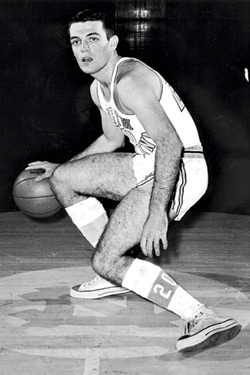

McGuire’s teams employed a signature New York playing style, taught alongside the catechism in city Catholic schools: give-and-go, pick-and-roll offense; zone defense. Walsh played guard, and was a deadly jump-shooter from twelve to fifteen feet out (all these years later, he’s still Fordham Prep’s second-highest career scorer) and one of the few white guys to play in Harlem’s summer Rucker League. But he was an even better defender—a smart, hard-nosed player who was rarely out of position. What really made McGuire’s system work, though, was the players’ fierce loyalty to him. McGuire was a friend of their dockworker and cop parents—or, in Walsh’s case, his father the union dentist. McGuire instilled an us-against-them mentality in his boys, tough city kids far from home going up against the rednecks and archenemies like N.C. State.

Walsh revered McGuire, so much so that after attending law school, he turned down a job with a major Wall Street firm and ended up joining McGuire’s coaching staff at South Carolina. He left only when offered a job by another member of the family, Larry Brown, who had been hired to coach the Denver Nuggets. Several years later, Walsh moved to the Indiana Pacers, first as an assistant coach and then as general manager, and turned around the woeful franchise. His masterstroke came in 1987, when, instead of giving in to intense pressure to draft local hero Steve Alford, Walsh selected Reggie Miller out of UCLA. Alford was gone from the NBA after four seasons; Miller, after spending many of his eighteen seasons tormenting the Knicks, is a lock to be elected to basketball’s Hall of Fame.

Walsh proved sharp not only at acquiring complementary parts, like the bruising Dale Davis and the underrated Rik Smits, but in the off-court deals that turned Indiana into one of the league’s most profitable franchises, like building Conseco Fieldhouse, a $183 million showpiece of an arena and museum. (He also, in 1993, hired Larry Brown to coach the Pacers.) The teams Walsh built around Miller never won a championship—they came closest in 2000, when they lost in the finals to the Kobe-and-Shaq-era Lakers—and he was in the middle of retooling the roster when disaster struck one night in Detroit: Pacers Ron Artest and Stephen Jackson went into the stands to fight belligerent Pistons fans. The aftermath of that nasty 2004 brawl slowly destroyed the team and wearied Walsh. In the past few years, Pacers players have been involved in a series of shootings, and last season, the team missed the playoffs and registered the worst attendance in the NBA. Ownership promised a shake-up. Walsh had hired Larry Bird to coach the Pacers in 1997, then promoted him to president of basketball operations in 2003. Bird made it clear that he eventually wanted to run the whole show. Walsh’s contract with the Pacers would end after the 2007–8 season, and he thought he was headed into retirement. But when the Knicks’ troubles continued and management shifts became inevitable, Walsh grew curious. So did an old friend from his South Carolina days, a basketball junkie from Brooklyn.

Dan Klores grew up to become a New York public-relations wizard, building a business with dozens of elite clients in the city’s business and media industries before becoming a filmmaker (he also wrote a Frank McGuire biography along the way). Walsh had provided contacts and advice for Black Magic, Klores’s documentary on the civil rights era and the unsung heroes of black-college basketball. Klores, watching the Knicks devolve into a laughingstock last season, returned the favor by advising Walsh on his next career move. “We talked about it day and night,” Klores says of Walsh’s concerns about joining the Knicks. “The issue was, ‘Are the Dolans gonna let him do his job?’ He didn’t care about money or anything else.”

And as luck would have it, just as Klores was working on selling the Knicks to Walsh, a friend in the NBA office, one with his own vast connections in the city, was selling Walsh to the Knicks.

David Stern loves all 30 NBA franchises equally. The commissioner would no doubt have been just as upset if a former team executive were suing for sexual harassment in Minneapolis or Portland or Memphis. But it was especially irritating to have the Knicks’ latest misdeeds delivered to his Manhattan desk every morning in Stern’s copy of the Times. He held his tongue until the humiliating Anucha Browne Sanders lawsuit had been tried, with the Knicks losing. Then Stern blasted the state of the once-proud franchise and Knicks owner Jim Dolan. “[The lawsuit] demonstrates that they’re not a model of intelligent management,” Stern told ESPN. “There were many checkpoints along the way where more decisive action would have eliminated this issue.”

“Donnie is very patient,” says Reggie Miller. “He’s brilliant at keeping the big picture clear in his mind.”

Clearly it was time for adult supervision of the Knicks. The season unfolded and the circus continued—with the Knicks losing by record numbers of points and star guard Stephon Marbury bolting the team during a feud with coach and general manager Isiah Thomas—while Stern worked quietly behind the scenes. “Jim Dolan does care more about the Knicks than people think he does,” says another NBA executive. “He’s accused of meddling in the team, but that wasn’t as big an issue as New York sportswriters made it out to be. If anything, he should have been more hands-on and moved Isiah out quicker. Now he was in essence saying to David and the league, ‘Help.’ David suggested Donnie.”

Dolan didn’t know Walsh personally, so Stern filled him in. And Walsh’s current employer in Indiana needed to approve the Knicks’ talking with him about a new job, so Stern acted as emissary. “David had to call [Pacers owner] Herb Simon and make sure it was acceptable to them,” says the NBA executive. “And Herb blessed it. The league is not typically involved in G.M.’s moving from team to team, but in this case, we saw three wins, frankly: a win for the league in terms of bringing a certain respectability to a franchise that was otherwise down, a win for Donnie personally because things had become flat at best in Indiana, and also a win for Jim Dolan.”

Stern deflects questions about his role in brokering the marriage. “When a franchise is in pain, as the Knicks have been, that’s something you just don’t want to see in your league,” he says. But he’s plainly thrilled with the short-term results. “A period of quietude for the Knicks is a very good thing,” Stern says. “Very good. The franchise is calling out for a period of calm. There’s enormous pressure in the world’s largest media market to do something and do it now, however prudent or not it may be. If there’s anyone well-suited to make careful analysis and do the best thing for the long-term health of the franchise, it’s Donnie. And one does get the sense the Knicks will improve just from the calm that has descended on the team.”

In April, on the night of his first day as Knicks boss, Walsh celebrated at Elio’s, the classic Upper East Side Italian restaurant, along with Stern, Klores, and Walsh’s brother Jimmy. As Walsh walked in, the bartender recognized him and began shouting. “Oh, man, you gotta help us out!” he said, speaking for thousands of Knicks fans. “You don’t have any idea how bad this is! We’re rooting for you! Welcome back!”

Maybe the third time will indeed be the charm. Because this homecoming thing hasn’t worked so well for the Knicks the first two times around.

Stephon Marbury comes from a very different time and place in New York basketball culture. Growing up in the Coney Island projects, Stephon was hyped from grade school as the Marbury who would finally deliver the family to the big time and the big money, after his three older brothers failed. Marbury and Walsh both learned early on what it’s like to deal with hoops hustlers, but by the time Marbury was a teen, the stakes and the pressures had escalated dramatically. So when Thomas and the Knicks traded for Marbury in January 2004, it was supposed to be a storybook ending for his career and a boon to the team. Marbury certainly became the dominant Knicks personality, but not in the way he and the team had dreamed: He’s become the symbol of the team’s bizarre decline, on the court and off. Marbury was in the middle of the sexual-harassment lawsuit that shamed the Knicks and cost the team’s owners $11.5 million.

Intertwined with Marbury’s unhappy saga was the 2005 hiring of Larry Brown to coach the Knicks. Brown, too, was supposed to be coming back to New York for a triumphant finale to his vagabond career. Instead, he led the Knicks for only one deeply weird season, marked by spats with Marbury and Thomas and dozens of lopsided losses, and ending with furtive roadside press conferences as he bickered with the Knicks’ owners.

Will it be different this time? Walsh savvily makes no promises and lowers expectations at every turn. “I sometimes go home at night and think, I must have been out of my mind. What the hell have I gotten myself into?” he says. “I think there are good basketball players here. I have respect for the guys who were here before—Larry, Isiah. But it didn’t work. And fixing it is gonna be hard, and it’s going to take time.”

Walsh copes with the stress by meditating. He sits in the most comfortable chair in his new apartment on the Upper West Side, closes his eyes, and tunes out the world. Walsh has been taking a Zen vacation at least once a day for 25 years now. No particular crisis in his life prompted his interest in meditation. “Maybe it was because I saw something on television about it,” Walsh says. “It clears my mind. I think too much, and if you’re not thinking all the time, maybe you put yourself in a better position to make a decision. But I’m not Zen-ing out all over the place.”

Indeed, all the years of wins and losses haven’t dulled Walsh’s passion. Last week, he exited cursing from a blowout Knicks loss to the Celtics—an exhibition-game loss. One of Walsh’s most vivid memories is from the 1995 playoff game at the Garden in which the Pacers beat the Knicks, with Reggie Miller scoring a ridiculous eight points in 8.9 seconds—and how Walsh, in a fit of fury, missed most of the incredible comeback. “I’m sitting there, and the Knicks get up six points; there’s like twenty seconds left,” he says. “I get disgusted. I’m pissed at our team. I get out of my seat. I go down the tunnel and I go into the locker room and I shut the door. I’m in there cursing: ‘Motherfuckers!’ All of a sudden there’s a knock on the door and it’s Mel Daniels: ‘Donnie! Reggie just tied the game!’ And I say, ‘Quit fucking with me! I’m not in the mood!’ I’m yelling at him, and he’s laughing. We find a TV. I see John Starks miss two foul shots; Reggie gets the rebound, and he gets fouled. I look at Mel and say, ‘Are you fucking telling me we’re gonna win this fucking game?’ ”

In some ways, it’s easy for Walsh to find tranquillity these days: His five children are long grown, and Judy, his wife of 45 years, has stayed in Indianapolis, with his beloved Bouvier dogs (“Rescue dogs,” he points out). “I’m working all the time,” Walsh says. “It wouldn’t be fair to her to come to New York and sit around.”

His current monomania aside, Walsh is the rare jock who reads books without pictures and wants to know more about the world outside of sports. Back in the day, he’d drop in to Max’s Kansas City. He’s an ardent Democrat, though his frequent donations to political campaigns often cross party lines. This summer, he contacted City Hall and asked if Michael Bloomberg had time for lunch. The mayor did. “Nice guy,” Bloomberg says. “He called me up, which I thought was an interesting ploy—ploy isn’t the right word—play. My suspicion is he wasn’t told to do it by the Dolans, but it was a very smart move, nevertheless.” Bloomberg has been splenetically angry at Jim Dolan ever since he led the opposition to the city’s bid for the 2012 Olympics. “We had a very nice lunch,” Bloomberg says. “I own two front-row tickets and two second-row tickets to Knicks games, that I pay the Dolans for. And I certainly wish him well.”

Walsh needs all the allies and good vibes he can get—which is exactly why his pal Klores, not the Dolans, suggested the lunch with Bloomberg, as well as goodwill calls to, among others, Governor David Paterson, Roger Ailes, Graydon Carter, and illustrious Knicks of old like Willis Reed and Earl Monroe. There’s already been plenty of stress for Walsh to meditate away. The most alarming moment came in June, when a doctor diagnosed tongue cancer. Walsh had been a chain-smoker for 50 years, but surgery cured his nicotine jones, and he’s been given a clean bill of health. (The cancer story was broken by Peter Vecsey, the Post’s powerful basketball columnist and another of Walsh’s close, longtime, well-connected friends.)

His first big Knicks move, back in April, was to fire Thomas as coach and general manager—though Walsh stopped short of chasing him out of town, as the sports pages were demanding. Partly that’s because Walsh has a reservoir of personal respect for Thomas, whom he hired in 2000 to coach the Pacers, and he wants to give Thomas the chance to recover his dignity out of the spotlight (and Thomas remains under contract to the Knicks for three more years). But the decision was also part of his attempt to lower the volume around the Knicks; appeasing the calls for Thomas’s exile would have only validated the shouters and made the screams louder the next time something went wrong.

To replace Thomas, Walsh jumped at the chance to hire Mike D’Antoni. D’Antoni was pushed out last spring after five excellent seasons directing the Phoenix Suns; his teams not only contended for the NBA title, but they played an entertaining up-tempo style crafted to exploit the talents of wondrous point guard Steve Nash. D’Antoni could have gone to the Chicago Bulls, a team that will win more games sooner than the Knicks, but he came to New York after a classic bit of Walsh courtship. D’Antoni was criticized in Phoenix for not caring about defense, and the Bulls suggested he hire an assistant coach who specialized in defense. “When Donnie flew out to Phoenix and talked to me, he conveyed to myself and to my wife, Laurel, that we want you—no ands, ifs, or buts,” D’Antoni says. “He conveyed a sense of ‘We really believe in what you do.’ ”

In June, Walsh made his next big statement, using his first draft pick as Knicks boss to choose six-foot-ten Italian teenager Danilo Gallinari. “There’s nobody out there on our team pulling everything together. I think Gallinari is that kind of player,” Walsh says. “He’s very good with the ball, he can draw a defense or pass. He’s a guy that can help other players.” Not, however, anytime soon: Gallinari hurt his back in July during a summer league game and only recently resumed practicing.

More surprising, however, is what Walsh hasn’t done: Dump Stephon Marbury. For months, the sports pages have reported that Walsh was on the verge of releasing Marbury or buying out his $21.9 million contract. Walsh insists it isn’t happening—yet, anyway. Turning Marbury loose now could come back to haunt the Knicks, he thinks, if the sullen guard signed with a division rival like Boston or Miami and played well. Better to hold on to Marbury, give him a clean slate, and hope he raises his trade value by being a good soldier for a change. If Marbury acts out again, releasing him is still possible—and it would be clear, once and for all, that the fault is entirely Marbury’s. In the meantime, Walsh has brought in point guard Chris Duhon, and Marbury has been relegated, at least temporarily, to the bench. “Donnie is very patient,” Reggie Miller says. “He’s brilliant at keeping the big picture clear in his mind.”

Rival teams see a conspiracy in which LeBron James is subtly steered to the league’s flagship team. “Aw, they’re just paranoid,” says Walsh.

Though fans and sportswriters are obsessed with the Marbury psychodrama, Walsh considers it a minor part of his plan. He’s made a number of subtle changes to improve the Knicks’ front office, adding former Orlando Magic general manager John Gabriel and Croatian scout Misho Ostarcevic to scour the world for new prospects. He’s also made more-symbolic moves, like hiring Ben Jobe, one of the coaching greats featured in Black Magic, as a scout.

At 67, Walsh (along with Rod Thorn of the Nets) is easily the oldest general manager in the NBA, and his references to long-gone greats like Rick Mount and Carl Braun can leave younger listeners mystified. His general-manager colleagues used to be mostly ex-players or coaches; the new generation includes an increasing share of number-crunchers, though the wave of stat-head executives isn’t yet as large as it is in Major League Baseball front offices. “What I see now are more of the guys who are into the statistics and the digital and all that, like the kid down in Houston,” Walsh says. “They analyze everything to the nth degree. They study it to the point where they know, ‘Well, if the guy can do this, this, and this, there’s a 99 percent chance he’s gonna be a starter in the NBA.’ It’s moving in the Moneyball direction. And it’s all good. I never thought I was any smarter than anybody out there.”

Walsh reads and understands the statistical analyses just fine. Yet he prefers to trust his eyes and instincts. And though there are whispers around the league that Walsh is well past his prime, he’s repeatedly shown the ability to adapt—unlike Isiah Thomas, who realized far too late that the NBA was deemphasizing the static, muscular half-court game in favor of speed and agility, and that the new salary-cap regulations made long-term contracts an enormous burden. Walsh, in transforming the Pacers after Reggie Miller, was ahead of the curve, targeting big men who could run and shoot, like Jermaine O’Neal. He also knows full well that no team wins championships these days without one of the league’s half-dozen superstars. “You want to believe that if we had five really good players, but not one great one, and we play the right way, we can win the championship,” Walsh says. “But it hasn’t happened that way. The last time it happened, probably, was with the Knicks, in 1973. In other words, how good, really, was Earl Monroe? How good was Bill Bradley? How good was DeBusschere? Were any of them, individually, as good as Jerry West? No. But as a team, they were a great team.”

Walsh’s words border on blasphemy: Those Knicks teams are venerated in the old-boy New York basketball subculture, held up as an exemplar of how the game should be played: intelligently and unselfishly. But Walsh is a pragmatist, and he knows the days of Dick Barnett are not coming back. “Every year you look up, and those are the guys that do it—Kobe or Shaq or Duncan or Garnett,” he says. “Or a kid coming up like Greg Oden. You’d love to have a chance to get a guy like him. But they come around once every fifteen, twenty years.”

He doesn’t have that long to wait, yet he is determined not to conduct a fire sale to jump-start the team. Instead, Walsh is focused on getting the Knicks below the salary cap and freeing up money to spend on new talent—just not immediately. “I’m not trying to get the cap down by the end of this season, or by the end of next year,” Walsh says. “I’m trying to get it down two years from now, in 2010.”

Which also happens to be the year that the NBA’s transcendent young superstar, LeBron James, becomes a free agent. Pure coincidence, Walsh says. Rival G.M.’s see a conspiracy in the making, however, in which the NBA subtly steers James to the league’s flagship team. “Aw, they’re just paranoid,” Walsh says with a laugh. “You know what’s interesting to me? What year do you think [Chris Bosh] is a free agent?” The gifted Toronto Raptors forward also hits the market in 2010. “Yes,” Walsh says. “And that kid’s a great player. But nobody talks about him. It’s all ‘Oh, you’ve got to get LeBron!’ Look, I understand that. But you look at that free-agent class, and there’s a lot of really good players in it.”

Yet none of them will come to the Garden, for even the fattest paycheck, if the Knicks remain a last-place carnival act. That’s why the Dolans paid millions to hire Walsh: to hold the fort for a couple of years and instill a sense of professionalism in the franchise again, making it attractive to the upper rank of free agents, who are selling their image as much as their game. LeBron—or Bosh, or Dwayne Wade—would become an exponentially bigger marketing star if he led the Knicks back to the top, which will be part of Walsh’s sales pitch. Will it work? “We’ll do it or we won’t,” he says with a shrug. Coming from anyone else, those words would sound passive. Coming from Walsh, they have the ring of something that hasn’t been associated with the Knicks in a very long time: serene, rational confidence.

As the regular season starts, Walsh says one of his biggest problems is finding a good spot to watch games at the Garden. He wants to be close to the court, but also inconspicuous. “I’m not there to socialize with fans,” he says. “I’m not scared about taking shit. If they want to yell at me, they can yell at me. But if you want to see me meditate, watch me watch a basketball game. Meditation means focusing on one thing. And that’s what I do. I just watch. I really get into it. Watching is part of the reason I love the game, now that I can’t play it.” With luck, and some street smarts, Donnie Walsh will make the Knicks worth watching again.