The last time the New York Knicks won a playoff series, a 15-year-old Carmelo Anthony had just finished his growth spurt. While the Knicks were outlasting the Miami Heat in the 2000 Eastern Conference semifinals in seven games, thanks to a phantom timeout call awarded to Latrell Sprewell (who admitted he hadn’t called one), young Carmelo Anthony was adjusting to what was happening to his body. He had grown four inches in less than a year, transforming from a skinny point guard to a massive Über-prospect who towered over his classmates at Towson Catholic High School outside Baltimore.

Carmelo remembers watching those games, when he’d return home after the 45-minute commute to the Baltimore projects known as “The Pharmacy,” made famous in HBO’s The Wire. “Patrick Ewing was the man,” he says to me. “Though mostly I just remember Spike [Lee].”

Of the seventeen men who played in that Game 7, only two are still in the NBA (Kurt Thomas, a backup forward with the Bulls, and Anthony Carter, currently Carmelo’s teammate with the Knicks). Between that night, May 21, 2000, and Sunday’s NBA playoffs Game One against the Boston Celtics, 3,984 days passed. During that time, the Knicks have hosted eight playoff games, winning only three. Since Carmelo, a four-time All-Star, entered the league in 2003, his former team, the Denver Nuggets, has never missed the postseason, and Anthony has played in a total of 45 playoff games (not counting Sunday’s contest). During that same period, the Knicks played four playoff games and lost each one. For the past six seasons, during the NBA playoffs, the Garden has gone dark.

Among the many attributes Carmelo has brought to this success-famished Knicks franchise, one of the less heralded is the basic fact that, to him, the playoffs are a normal, obvious progression from the regular season, rather than something you have to pinch yourself about to believe is really happening. Knicks fans are doing backflips that there are real, live playoff games to watch. That the last decade of pain—amazing, comical, ridiculous pain—has led to a return to relevance.

But this is nothing new to Carmelo. “The fans and some of the players on the team, like people in the organization, they haven’t really experienced what it’s like being in the playoffs,” he says. “The energy level. How much fun it is to prepare for a playoff game with the fans the way they are. It’s amazing. I wouldn’t be surprised if Knicks fans were tailgating. They’ll be tailgating out there. I’ll be out there with them.”

Forgive Carmelo for not understanding the traffic Armageddon a tailgate outside Penn Station would induce. He is new here, even if this is his home.

This has perhaps been the strangest season in recent memory both for the Knicks and Carmelo Anthony. For all the outrage directed at LeBron James and his much-derided ESPN event “The Decision” (in which he took an hour of prime-time programming to break the hearts of Cleveland Cavaliers fans and sell Vitaminwater), the Knicks and Carmelo have spent every minute since that program trying to be exactly like LeBron.

LeBron’s decision to go to a super-team in Miami (a team that has so far been more super in theory than practice) caused nothing but envy for both the Knicks and Carmelo. The Knicks, having signed Amar’e Stoudemire, immediately set about trying to find another superstar to team with him, Heat style. And Carmelo, in Denver, sullen, bored, and heading toward the end of a contract with a labor war looming, set about trying to get himself out of town, to get himself a superstar running mate or two, and of course to get himself paid. The Knicks and Carmelo were such a match they even flirted at Carmelo’s wedding, held the weekend after LeBron’s decision. (Stoudemire had to apologize to the Nuggets owner for all the Knicks talk at the event.) The Knicks hadn’t had a player of Stoudemire’s caliber since Ewing; the footsie with Carmelo was a wish for two of them.

And then something strange and wonderful happened: The Knicks, with Stoudemire, got good. Not dominant, mind you, but fun, giddy, and occasionally thrilling—an offensive juggernaut that featured Stoudemire, having his best season, surrounded by young, emerging players like Danilo Gallinari, Raymond Felton, Landry Fields, and Wilson Chandler, ideally suited for the system that coach Mike D’Antoni had desperately wanted to run for two years. The Knicks didn’t always win, but they lit up the Garden as it hadn’t been lit in years. Following a wild, ecstatic, nationally televised loss to the defending Eastern Conference champion Celtics in December, Boston guard Paul Pierce said, “The Knicks have arrived.” After a decade of Isiah Thomas and Jim Dolan and Stephon Marbury and Anucha Browne Sanders, this Knicks team felt like a purifying cleanse. We had earned this.

Still, Carmelo loomed. The Nets, desperate to justify those Jay-Z billboards and the construction zone on Atlantic Avenue, were willing to trade virtually their whole franchise for him, but Carmelo, who wielded his reluctance to sign a contract extension like a scepter, refused to go along. He, and his professional-celebrity wife LaLa Vazquez (who grew up in Brooklyn), wanted the Knicks. But did the Knicks want him anymore? Were they willing to give away all the young talent they had stockpiled for one man? Carmelo was the central story line of the first half of the NBA season, to the exhaustion of anyone who loved the game, including even him. At the NBA All-Star Game, Carmelo was the lone topic of conversation. “None of the other players got attention,” he says. “I don’t want that kind of attention no more. That was too much.”

Then the trade went through. The Knicks sent all those young guys, all but Fields, to Denver for Carmelo and veteran point guard Chauncey Billups. At first, many (including me) debated the wisdom of the trade, considering the Knicks had gutted their free-flowing, exuberant roster and sacrificed hard-earned salary-cap room in the midst of their first playoff season in a decade for a man whose offensive strengths (isolation, hop-step jumpers) seemed so ill-suited to D’Antoni’s system. The trade was also questionable because the Knicks could have called Carmelo’s bluff and hoped to try and sign him as a free agent, post-lockout, avoiding the need to give up so many players.

“Man, people just freak out here. It’s mostly funny. I just play basketball, you know?”

But the naysayers were almost immediately drowned out by an electrified crowd, one whose fervor bordered on religious mania, during Carmelo’s first game against the Milwaukee Bucks. The JumboTron showed quotes from Carmelo about “coming home,” and when he appeared in the team huddle, the Garden—in a year when it has been louder than it has been in so, so long—burst into flames. The arguments against the trade were rendered moot within seconds: Knicks fans had their savior. “That night was one of the best moments I’ve ever been a part of,” Carmelo says. “I’ve played in national championships, gold-medal games, conference-finals games. But that game is the one.” Carmelo did not play well, by his own admission, mostly because he had come straight off a flight from L.A. to a press conference and then to the game; he hadn’t even met most of his new teammates yet. “I didn’t have no legs, I can tell you that,” he says. “What got me through was the adrenaline, the energy that was in the building. There is nothing like Knicks fans.”

In the next months, Carmelo would learn this in every possible way. Since the trade, the Knicks have won seven in a row, lost six in a row, beat the vaunted Miami Heat, and lost to the wretched Cleveland Cavaliers (twice). This inconsistency, which was to be expected with a team with such dramatic roster turnover but was still disheartening to watch, along with the intense anticipation of Carmelo’s arrival, led to an accelerated timeline of judgment: Within a month of being the most beloved athlete in New York, he was being booed. “Knicks fans are intense,” he says. “They’re very loyal, very straightforward. They don’t hold no punches. That’s what makes them who they are. And at the end of the day, the stuff we get booed for, not playing hard, messing up on the sideline, we deserve it. And it’s stuff we can correct.”

In person, Carmelo is disarmingly casual about pretty much everything. He speaks in a slow, laconic drawl, and seems bemused by all the fuss he causes. Every big-name athlete who comes to New York has to devise a strategy to deal with The Media. Some attempt to ingratiate themselves (Nick Swisher), some are combative (Randy Johnson), some are both (Alex Rodriguez), and some magically dance between the raindrops (Derek Jeter). Carmelo sees the media circus the way a native New Yorker might: With wry humor and the perspective that, hey, this is just what happens here—it’s kinda fun. After a March loss to Detroit, one that started a six-game losing streak, Carmelo left the visiting team’s locker room without talking to reporters. This led to the “Carmelo Fails Yet Again” and “Carmelo Hides on the Bus!” headlines that inevitably appear when the maw is not fed. “Man, people just freak out here,” Carmelo says, chuckling in a way that makes it clear he’s hardly offended. “It’s just something you deal with. It’s mostly funny. I just play basketball, you know?”

But everybody wants something, and that is part of the job description when you are the savior of the Knicks, with a fan base so burned by the Isiah years that, even in its excitement, it’s always waiting for the hatchet to drop again. (If it’s any reassurance, Carmelo says he hasn’t talked to Isiah “in years” and met Jim Dolan for the first time during the All-Star break.) And what this fan base wants more than anything is, of course, a championship.

So, does Carmelo make that more likely? He’s certainly not the league’s most suffocating defender or fierce rebounder, and his spot-up game would be better complemented by a tougher presence underneath than Amar’e, who has turned into mostly a jump-shooter himself. But Carmelo is one of the most accomplished scorers in NBA history, and advanced statistical metrics consistently confirm what fans have known for years: When the score is tied in the final seconds, there’s no one in the game you want to have the ball more than Carmelo. The best part of his game, his ability to get off his own shot as time expires in a close contest, is his favorite part of his game. “It’s an adrenaline rush like nothing else,” he says. “It makes it even that much better because the opposing team knows who the ball is going to. They still can’t stop it. That’s the extra motivation.”

But is this a championship team? Right now? Probably not yet. “This is a long-term plan,” Carmelo says. “We’re trying to build a mansion here.” What he and Stoudemire promise—working off the LeBron blueprint again—is the allure of more, the enticement of two superstars in the biggest, best city in the world, combining with yet another superstar to produce the Biggest and Baddest of All Knicks Teams. The ideal candidate is Magic center Dwight Howard, who is unhappy in Orlando, a free agent after next year, and a close friend of Carmelo’s. (The two filmed a not-yet-released movie called Amazing last fall in China. Carmelo says the experience was fun, but not nearly as much fun as cross-dressing and playing in the “Laser Cats” sketch on SNL.) Another option is Chris Paul—who gave a toast at Carmelo’s wedding, and also talked about going to the Knicks with him and Amar’e. But Carmelo isn’t talking about that yet. He wants to get through the craziest season of his career first. “I’m going on a trip when this season is over,” he says. “Just decompress and think about what really just happened.”

“This is a long-term plan. We’re trying to build a mansion here.”

But there are still the playoffs, this year and in the future. I asked Carmelo if a championship would compare with winning the gold medal with Team USA (and LeBron and Dwyane Wade) at the Olympics three years ago. “Better. Way better,” he says. “Winning the championship here, for these fans, in this city, that would be amazing.” He pauses. “Man, can you imagine the parade?”

When Carmelo’s handlers asked if I’d be interested in coming with him to visit the Red Hook West housing projects in Brooklyn where he was born and lived until he was 8, I said yes, obviously, but with considerable skepticism. Much of this “Carmelo comes home!” story line that accompanied his arrival has seemed to be MSG hype. After all, he left when he was 8. What was he going to show me? Over here, I ate some candy. Over there, I watched some cartoons. Here, I skinned my knee.

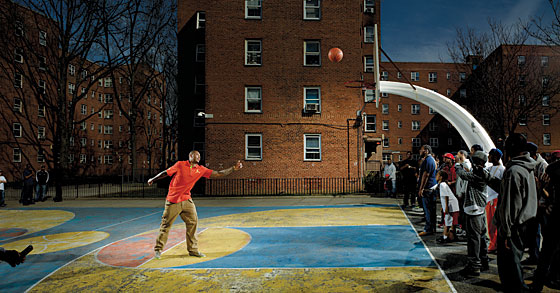

It took about 30 seconds at the cracked, faded basketball court right next to the building where Anthony was raised for that skepticism to vanish. While Carmelo waited in an SUV as the photographers for this story set up their equipment, I watched as hundreds of Red Hook West residents converged upon the court. “The only time people come here is when something’s going on with Carmelo,” said 18-year-old Rock Harris, a resident of the housing project, explaining how everyone was tipped off.

The first person to walk up to me was Ramona Hernandez, 65, a short, round woman with wide eyes and a ripped T-shirt, brandishing a photo. “Look, look, that’s him,” she said. Hernandez was holding a kindergarten picture from P.S. 27, class K-136, 1989–90, that featured a tall, grinning kid in wide blue lapels already dwarfing his classmates. (Carmelo was a very cute kid.) “That girl right there is my niece. Do you think he would sign this for me? Can you ask him?” Right behind her was Harris, who had a laminated copy of a February Daily News story. The item was about Anthony’s journey from Red Hook to Baltimore and featured a picture of Harris and his friend Earl Miranda, who made sure to point out to me which guy was which in the picture. “They quoted me,” Miranda said, “because I’m better looking.”

Miranda was also quoted because he lives in Anthony’s old apartment. Right there, 79 Lorraine Street, Unit 1C, is where Carmelo spent the first eight years of his life, and where Miranda has spent his first nineteen. “We moved in when they moved out,” Miranda said. “I’m gonna try to get him to take a look at the place today. He’s never done that before.”

Anthony, followed by security and his handlers, emerged from the SUV, and havoc ensued. Harris, jumping up and down, handed me his phone and said, “Reporter man, film me, film me.” I obliged with a 30-second tracking shot that ended with Carmelo putting his arm around Harris and smiling. Carmelo then hugged Miranda and about 45 other people. Hernandez showed him the kindergarten photo, and Carmelo asked if he could have it. Hernandez was amusingly shocked. “He wants it! I just wanted him to sign it! It has my niece in it!”

As Carmelo dribbled and shot on the same court where he dribbled and shot as a grade-schooler, and as our photographers snapped away, he began to chat with an older man he recognized, one of the hundreds now standing on the sidelines. “Ronnie!” he said. “Damn, it’s been forever.” Ronnie was laughing but appeared to be giving Carmelo some considerable gruff. “Yeah, you ain’t nothin’, ” Ronnie said, over and over, laughing and laughing, along with Carmelo.

“Ronnie” was Ronald Brown, 48, who has lived in the Red Hook West projects his whole life. He also used to play basketball with Carmelo’s father. In the oft-told history of Carmelo’s journey from Red Hook to Baltimore to Syracuse University to the NBA, his father, who died of cancer when Carmelo was 2, is a muted footnote, the tragedy that spurs our hero onto his journey. But to Ronnie, Carmelo Sr. is a legend. A few years younger than Carmelo’s father, he was one of his closest friends and was with him throughout his fight with cancer. “Lots of people don’t know his pops,” he said. “I tell you, his dad was better. He was the best. Carmelo can’t carry his jock.” He then repeated this to Carmelo. “You couldn’t hold your dad’s jock, you hear that?” It was a relief to me that everyone was still laughing.

Carmelo, wearing an orange Jordan-brand polo and a massive gold watch, continued to dribble as the crowd grew and grew. I asked him if he was going to go see his old apartment. “I’m working my way up to that,” he said, smiling. “Not sure I’m ready for that yet.” Nonetheless, when the shoot ended, he grabbed Miranda and his bodyguard and sprinted into Apartment 1C and stayed inside for about ten minutes as the crowd migrated to the door.

No one else was allowed in to witness the tour, but when Carmelo came out, he was beaming. “Wow, man, place is exactly the same,” he said. “Finally got to go see that. That was something.” He glided through the crowd, signing and posing and still somehow moving forward. He paused and looked back at his old home. “I suppose I can just come see this place anytime I want to now. That’s kinda cool. This is where I live now. This is where I do what I do.”

E-mail: will.leitch@nymag.com.