One year in, the Knicks-Nets rivalry is a bit more of a hopeful theoretical than a concrete reality. For all the competition for headlines, the atmosphere of the actual games between the two teams hasn’t quite reflected the ongoing arms race, at least inside the arena. At Barclays, the crowd is roughly 50-50 Nets-Knicks fans, an even split that might be exciting when Florida and Georgia are playing a neutral-site football game in Jacksonville but isn’t exactly the snarling, hostile home-court advantage the Nets were hoping for in their brand-new building. And at MSG, the Nets have essentially just been “Opponent”—they generate a livelier atmosphere than when the Knicks play, say, the Sacramento Kings, but nothing compared to the Heat or the Lakers.

If that’s gonna change, this is the year. As the season tips off, the Nets have unleashed a full-fledged assault on the Knicks. Nets brass claim New York is big enough for two teams and two arenas, but the Nets have never made a secret of their desire to take the town from their rivals. (Remember those Jay Z–Mikhail Prokhorov billboards near MSG?) The Nets see the Knicks as a franchise that has grown fat and lazy with an owner who has lost touch. They see weakness.

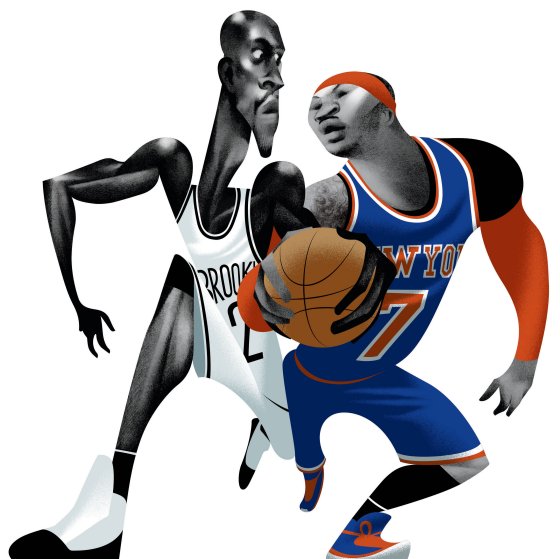

So this off-season, unsatisfied with their successful but ultimately disappointing first season, the Nets attacked. First they brought in franchise icon (and recent Knick) Jason Kidd to coach. Then they made the all-in move to end all all-in moves, bringing in Kevin Garnett and Paul Pierce from Boston for one last championship run, a brash move that left Knicks owner Jim Dolan sputtering—trading for the Raptors’ Andrea Bargnani and then suddenly demoting general manager Glen Grunwald.

But let’s not kid ourselves: Acquiring Garnett and Pierce was a crazy, potentially devastating move, and it’s going to start a competition that might very well destroy both franchises—one in which each seems more focused on besting the other (often in the papers) than on competing with the rest of the NBA. It’s a kind of mutually assured destruction.

More than in any other league, in the NBA teams tend to think that if you’re not building a championship contender, you’re not building anything at all. Because one player can make so much difference in basketball, the number of teams that can legitimately call themselves championship contenders is extremely small—no matter how good Barry Bonds or Dan Marino were, they needed a supporting cast much more than Michael Jordan did or LeBron James does. And the need to build around superstars means there are no dark-horse champions in the NBA. In Major League Baseball, the NFL, and the NHL, if you just sneak into the playoffs, you could get hot at the right time and win the whole thing. (Ask the St. Louis Cardinals or, for that matter, the New York Giants.) But of all the NBA title winners of the past 30 years, only three (the ’03–’04 Pistons, the ’07–’08 Celtics, and the ’10–’11 Mavericks) didn’t win multiple championships.

And, lately, the teams that do compete tend to follow a pretty clear pattern. This season, you can make an argument that only, oh, three teams can call themselves really legitimate title contenders: Miami, San Antonio, and Oklahoma City. Let’s look at those three teams: How have they done it? Miami has the easiest answer: It has LeBron James, one of the best basketball players of all time. But San Antonio and Oklahoma City are perhaps more instructive—models of prudence in an era when the worst mistake a franchise can make is to give superstar money to the wrong guy. See, in the NBA, awarding a huge-money contract to a player who can’t live up to it is particularly catastrophic, because the salary cap is not only a cap, it’s also a ruler whacked across the knuckles of offending owners. Without getting too technical on you, the collective-bargaining agreement attempts to make every player affordable to every team, no matter the market, establishing a variety of more or less fixed salary levels into which teams can slot players. This means that, if you make a mistake on a big-ticket player, you can’t just sign another one to take his place. The NBA is not the league in which you can just throw money at talent.

Thus, the success of San Antonio and Oklahoma City. Those are two franchises, located in smallish towns with patient, loyal fan bases and generally sedate local media, that have taken the long view: Each found a superstar and built around him slowly, with no concern for headlines or tabloid shit-shows. They were careful with the salary cap, never traded away draft picks, and were happy to pick an international player who might not help them for a few years. They were … prudent. The next tier of teams is working on the same model, and while the ’07–’08 Boston Celtics (led by much younger versions of Pierce and Garnett) are the obvious outlier example, a team of superstars thrown together on the fly that managed to win a championship, theirs is the only real success story of that kind in the salary-cap era.

The Knicks, needless to say, have been the furthest thing from prudent. And it’s worth pausing for a moment to point out how insane the Knicks’ worldview in this regard is. Most franchises are afraid to go through austerity periods like the Knicks endured under general manager and president Donnie Walsh from 2008 to 2011, because fans don’t like to pay to watch losing teams—punting a couple of seasons to clean up your salary cap and collect draft picks might be smart strategy, but it can be murder to the bottom line. But the Knicks are the incredibly rare franchise that has never had to worry about this: They sell out the Garden even when the team stinks! Given that luxury, it’s flabbergasting, really, that the team never allows a conscientious rebuilding plan to reach fruition. And this is the ongoing Knicks tragedy: They’re not a franchise that has to win every year … but they act like one.

Take the era when Walsh was in charge. Charged with cleaning up the Dumpster fire Isiah Thomas had left him, Walsh stripped the team clean, hoarding draft picks and clearing up the gnarled cap situation, letting the Knicks flounder as the process took shape. By 2010, that plan was starting to bear fruit: The Knicks were in a position to keep all their talent in-house and sign a big free agent in the 2011 off-season, probably Denver’s Carmelo Anthony, who wanted to be a Knick. But Jim Dolan and Knicks brass got antsy and, looking to make a big splash mid-season, traded away much of that talent, along with future draft picks, for Anthony, who then signed the contract extension everyone knew he was going to all along.

Carmelo has been terrific for the Knicks, but he hasn’t been LeBron, and thus he hasn’t been enough. And in order to complement him, the Knicks have gone back to the building-the-airplane-while-it’s-in-the-air chaos of the Isiah days, hitting the low point with the trade for Bargnani, in which they gave up a future first-round pick they didn’t have for a player they don’t have a position for. Oh, and they also threw in two second-round picks.

The Nets could have learned from the Knicks’ failures and excesses. Instead, Brooklyn has doubled down on them. From the beginning, it was obvious that the Nets organization believed that supplanting the Knicks (and not building a competitive on-court product) was their highest priority. It was as if they’d seen the tabloids thrash the Knicks every day for a decade (while ignoring the New Jersey version of the Nets) and, instead of taking the right lesson (“Let’s not run our franchise that way”), they learned exactly the wrong one: “Oh, that’s how to get attention!”

Not every decision the Nets have made has been disastrous—the signing of Deron Williams made sense, as did the resigning of an underrated Brook Lopez. But almost nothing else has worked. The trade for Joe Johnson and Gerald Wallace before last season was a disaster; Wallace gave the Nets almost nothing, and this season he’s gone. Johnson is now paid the league’s fifth-highest salary ($21.4 million! More than LeBron!) to be the second-best shooting guard on his own team. And their trade this off-season for Pierce and Garnett—two aging stars too old to win much for the last team they played for—is tragic confirmation that the Nets are on the same suicide track as the Knicks. They’ve now mortgaged even more of the future than the Knicks have. With the trade, the Nets not only have no space or money to add players, they now own only one draft pick—a piddly second-rounder—until 2018. That is so self-destructive that NBA rules actually ban it: You’re not allowed to trade first-round draft picks in consecutive years, something the Nets of course found a way around. The team the Nets have right now? The one full of guys in their thirties? That’s it. For the next five years. And they’re paying insanely for it: Counting the tax payment for going over the salary cap, Prokhorov & Co. will spend north of $180 million in salary and luxury tax on this year’s team—a team that brought in, according to Forbes’s most recent annual estimation, only $84 million in revenue.

Do the Nets have a better chance of winning a title than they did last year? I suppose, though the rest of the Eastern Conference is better, too, particularly with the return of Chicago’s Derrick Rose from injury (although the Atlantic Division is actually worse, which means the Knicks and Nets could put up gaudy records without playing great basketball). But if the Nets don’t win this year—and despite those possible improvements, they’re extremely unlikely to—the team is just going to get older and worse and more expensive. In order to stave off a reckoning, they’ll have to make more Hail Mary moves like they have in the past two seasons, just like the Knicks have always done. This is two franchises nuking each other while Miami, safely away from the fallout, laughs.

This year should be the best year yet for the Nets-Knicks rivalry. Enjoy it. Because both teams are about to get a ton worse.

You can write to Leitch at will.leitch@nymag.com.