Someone once described the so-called Boom Boom Room, the lounge on the eighteenth floor of the Standard Hotel, as being like “the hottest nightclub in Sweden.” With its beige tufted-leather banquettes, brass railings, and giant flowerlike column in the center of the room, it struck me at first as an unholy marriage of Maxwell’s Plum, Studio 54, and Regine’s—but on a spaceship. Sort of. In any case, when you walk in for the first time, you feel as if you have been transported to a better place and a more interesting time … L.A. in the eighties? Vegas in the sixties? Berlin in the twenties? Decadent epochs, all. Even the view is too much. When you stand in the center of the club, you can see the Statue of Liberty and, with just a slight rotation of the head, the Empire State Building. If you were to spin in circles like Diana Ross, you would feel like you were inside a human-size zoetrope.

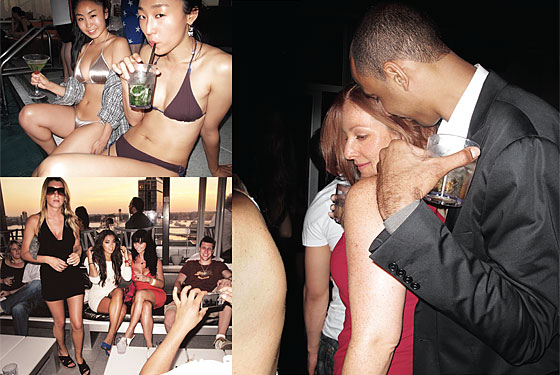

Tonight the Boom Boom Room is the site of a private record-release party for Alicia Keys, who is here with her boyfriend, Swizz Beatz, and her mother. Tyson Beckford and Spike Lee are among the throng (so early nineties). Beyoncé and Jay-Z (so 2010) arrive, the D.J. drops the needle on “Empire of State of Mind,” and Keys leans into the chorus (“These streets will make you feel brand new / Big lights will inspi-ah you”) Everyone smokes on the vertiginous step-out balconies. The staff, who are dressed like flight attendants (but from a different time!), seem to be as drunk as the guests (but cuter). People are dancing, but mostly they are drinking. And gulping down little hamburgers like they are at a Fourth of July picnic, grease dripping off their happy chins.

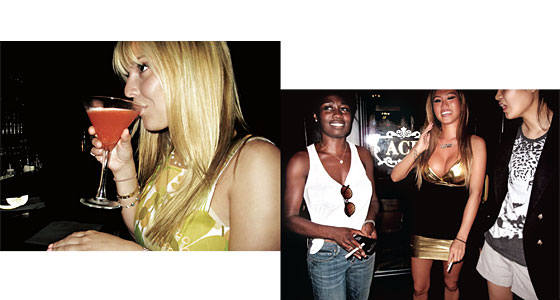

The scene outside the hotel is almost as mesmerizing: SUVs and limousines—clown cars all—are disgorging dozens of pretty ladies, all of whom look like Kardashians. Everywhere I look I see Khloés and Kims and Kourtneys and Kylies—some blonde, some drunk, some plump, some skinny, with clipped-in curls and major shoes moving with strange purpose in clouds of perfume. They seem to be heading in the direction of the Hotel Gansevoort, to its nightclub, Provocateur, designed to be “female friendly” through the use of purple and pink décor and “sensual music.”

After a long night of partying in the neighborhood, I head back to the Standard Grill around 3 a.m. and, to my delight, happen upon a group of women I know who are at the tail end of a hen party, and they are lit to the gills. At first, they are mortified to see me, and it takes a minute for me to realize that they never expected to run into anyone they know here. What happens in the meatpacking district stays in the meatpacking district. Manhattanites now treat the neighborhood as Vegas-on-the-Hudson.

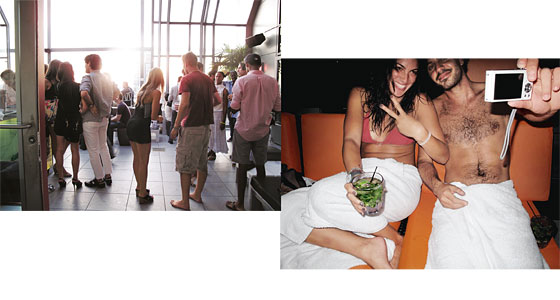

But this is not the only neighborhood that has been transformed by one or more Miami-, L.A.-, or Vegas-style hotel-nightlife complexes. Just try finding a seat in the lobby of the Ace or the Bowery or the Gramercy on any given night. Getting a table at the Breslin? A couch to call your own at the Rose Bar? Fat chance, Bozo. One steamy Tuesday evening in June I met friends at the Ace Hotel at 6 p.m. to go to the Breslin, and we were told there were exactly 1 million people ahead of us. Why were so many people so excited to be there at that uncool hour? We headed next door to the hotel lobby—the place to hang out in the city right now—and, again, not a single vacant stool or couch. Everyone seemed profoundly engaged in either a laptop, a Rubik’s cube, or some sort of palm device. And they all appeared to be in the band MGMT.

It has been creeping up on us for a several years now, but the transformation is complete: Manhattan’s nightlife is practically synonymous with its hotels. After decades of irrelevancy—the last place on Earth most New Yorkers would go to be at the center of it all—hotels have become, for better or worse, a cultural force in the city again. They are at the forefront of interior design, hire the most celebrated chefs, host the most talked-about parties, and generally loom large in the psyches of tourists and locals alike who feel they must get in to see them. How did this happen? Somehow, a handful of stylish boutique hotels in midtown spawned an army of imitators that marched out across the country to places like Las Vegas and Miami, where the volume got turned up—way up—on their lounge-y lobby scenes and then someone had the bright idea of just putting a full-fledged disco in the building for guests to slosh around in. All of this has boomeranged on New York City and created a kind of happening-hotel arms race in which we now find ourselves with a multitude of (somewhat similar) options: Which young-adult theme park with modern-day Playboy club and pool on the roof do I want to go to tonight?

The city is crawling with new hotels, with more opening by the month. Since 2008, nearly 14,000 hotel rooms have been added to the 68,000 that already existed—a result of the boom years, when hotel occupancy averaged 85 percent and the average daily room rate climbed by 53 percent. Remarkably, by the end of the year another 4,000 rooms will be added through dozens of new hotels that were too far along to stop construction when the recession hit. Many of them are independent—or “boutique” or “unique” or “lifestyle” hotels. Indeed, New York City is now the “world capital of unusual boutique hotels,” says Bjorn Hanson, professor of hospitality and tourism at New York University, partly because the city is filled with quirky buildings in non-hotel neighborhoods that were attractively priced and ripe for development.

When I moved to Great Jones Street seven years ago, there was not a single hotel in the neighborhood. Today, especially during the hot summer months, the boozy clarion call—whoo-hooo!—of drunken revelers emanates from nearly a dozen hotel-nightlife complexes. From the roof of the building I have just recently vacated (partly because of this stampede), I could see Lafayette House on 4th Street where the artist Dash Snow died of a drug overdose; the crazy late-night parties taking place in the penthouse of the too-tall Cooper Square Hotel; the Bowery Hotel’s sprawling faux-old-world second-floor party space where J.Lo threw Marc Anthony a 40th-birthday bash; the three new hotels on once-sleepy Crosby Street; the Thompson Lower East Side, the Rivington, and the troubled Nolitan (which got caught building too many floors). I could also see into the entire length of the 8,500-square-foot penthouse apartment at 40 Bond that belongs to the man who gets the credit or the blame for bringing this pox upon Manhattan: Ian Schrager.

When Schrager started the boutique-hotel revolution with Morgans, Royalton, and Paramount in the late eighties—after getting out of jail for tax evasion—he was essentially trying to figure out a way to stay in the nightlife business without opening a nightclub. The Royalton and Paramount in particular, with their dark hallways, sleek-comic Philippe Starck revelations, and catwalklike lobbies, managed to almost re-create the exquisite mix of fame and art, money and drugs, sex and ambition that were the hallmarks of Schrager’s Studio 54. The Schrager effect was, of course, huge: Design-y, nightlife-y, high-concept-y hotels sprouted up in cities all over the world. The W brand, based on the Schrager model, launched in New York in 1998 and then metastasized—there are now 25 of them. Schrager himself opened hotels in Miami, London, San Francisco—each one more slick and fanciful than the next. In fact, if you were to try to pinpoint the exact moment when the boutique hotel evolved into something more decadent, you’d have to look no further than Schrager’s over-the-top Delano in Miami, with its thumping lobby and poolside fashion show.

It is so easy to spot Michael Achenbaum in the crowded Starbucks on the corner of 29th and Park. For one, he is carrying two hard hats. For another, he looks just as I had pictured: tall and tan with perfectly manicured stubble. Though he is 37 and once worked in finance, he could strike you as a D.J. perhaps or a modeling agent. I am meeting him to tour the nearly finished Gansevoort Park Avenue hotel across the street, his latest Shangri La–in–the–city that will open later this summer.

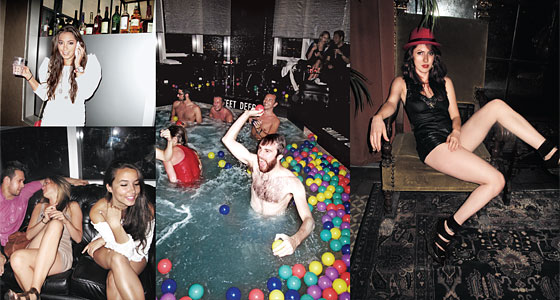

Achenbaum spreads out the architectural renderings as he explains his grand plans for what begins to sound an awful lot like a disco—turned inside out. Like the Gansevoort in the meatpacking district, this hotel will have an elaborate rooftop pool complex, part of a three-level nightclub with a sound system designed by the engineer who did Pacha in New York and Space in Miami. “Every speaker, every subwoofer is pointed back into the space,” he says. “I have nothing that’s pointed outwards, like, intentionally. I’m very conscientious.” There will be a nine-foot-high glass wall around much of the pool area that he hopes will contain the nightly bust-up. There will be step-out balconies and wraparound terraces off nearly every public space so guests can “grab a smoke, which is a huge thing in the city,” says Achenbaum. Inside a VIP area called the Blue Room, there will be three massive Deborah Anderson photographs of a semi-naked girl. “When Steven Meisel doesn’t get the job,” says Achenbaum, “Deborah does. She shot the cover of Playboy.” In one of the photographs, the Gansevoort Girl is kissing herself in a double exposure.

I ask Achenbaum what he thinks about the new hotels opening all across 29th Street, the latest groovy-baby hotel corridor to spring seemingly out of nowhere. “Have you seen the Ace Hotel? It’s very hipster. I mean, it’s fine. It’s not my demographic. We’re trying for a balance between people who are a little bit more mature and people who are young and excited.”

Ah, yes. Young and excited. The coin of the realm in the meatpacking district, where Achenbaum launched himself into nightlife-neighborhood ignominy; he and the Gansevoort became a symbol for all that is troubling about the slick, Vegas-y turn that this once charmingly rough-hewn corner of the city has taken. “We have been a hot-button hotel,” he says, “blamed for a lot of things that I really don’t think we did. People still claim they can hear our rooftop, and I know it’s just not possible.”

At one point, as Achenbaum describes the exterior of the new building—30-foot-high glass-curtain wall here, black granite stonework there—he points to a big gash of red that will run down the length of the façade. It represents a sixteen-story light column that will change colors like the light columns at all Gansevoort product, as Achenbaum likes to say. “Light is a big element of what we do.” Suddenly a Lurch-like fellow who is sitting just inches away from us at Starbucks sputters to life. “You want my opinion?” he says. We both stare at him. He points to the red light column on the drawing. “That looks ugly. I wouldn’t keep that.”

“O-kay,” says Achenbaum.

“That’s just my opinion,” says Lurch.

“If you are a 19-year-old runaway,” says Sean MacPherson, “we want to be your hotel.”

As Achenbaum and I pick through the construction site on 29th and Park, he quietly stews over Lurch’s comments. “The fact is that most of our customers love the light columns. The fact is that it’s dramatic. The fact is that it’s talked about all over the world. So there has to be a light column.” On the roof, he shows me a small detail that he seems particularly proud of: He has instructed the crew to curve the top of the railing that surrounds the outdoor lounge so that hotel visitors won’t be able to set their drinks down on them like they do at the meatpacking-meets-Miami pool parties. Passersby on the street below can at least take some small measure of comfort in that.

“You know, the role of café society—the society that takes place in public—has always been integral to the development of a city like New York,” says André Balazs. We are sitting at the Standard Grill, the restaurant on the ground floor of his hotel that has been packed from the minute it opened. Balazs is a triumph of good grooming in his bespoke navy suit and crisp white shirt. The fact that he is carrying a cane due to a broken ankle only adds to the sense that he has stepped right out of a Bond film. “If it’s true that somehow people are embracing hotel culture more than they were six or seven years ago, it could be because it allows friends to gather in a situation that’s a little easier, more homey, than a straight-up restaurant,” he says. “People are gravitating toward hotels because it’s a way to kind of feel you are well off even if you may not be.”

Stylish hotels, of course, have always been about escapism, places where one gets to live on borrowed luxury. “All good hotels have common characteristics,” says Balazs. “They make you feel safe. And after they make you feel safe they allow you to let down your inhibitions. And very few people can afford the level of service that you have in a good hotel. For example, we don’t put towel bars in our rooms because part of the joy of living in a hotel is the abandon that lets you throw the towel on the floor.”

Just then, a woman from the neighborhood comes up to say hello to Balazs and tells him she eats breakfast here every day. “It certainly was our goal to make it a New Yorkers’ place,” he says as she leaves. “Our people who sleep here come from other parts of the world, but at the end of the day, all of the public facilities are local businesses.” He ticks off the venues: the restaurant, the beer garden, the two nightclubs at the top of the building. “We have more operations, more bars, under one license, than anyone else in the city.”

Indeed, part of the reason for the hotel-as-nightlife-complex boom is that it is easier to open a hotel than a nightclub in Manhattan these days. No one wants a big throbbing disco in their backyard, but hotels are sold as something that enhances a neighborhood and increases property values. But once a hotel has its liquor license, it only makes sense to maximize its potential.

Not that Balazs wants to be associated with other nightlife hotels. When I ask him about the Gansevoort, he chooses his words carefully at first. “We have as our neighbor the Gansevoort Hotel,” he says. “The Bowery Hotel has as its neighbor the Cooper Square Hotel.” And then he starts to laugh. “I would say that the relationship between the two hotels on each side of town is similar. The Cooper Square is such a travesty of architecture. It’s really sad. The rooms are awful. Not that they haven’t spent a lot of money, but the concept …” His face wrinkles up like he’s smelling ten-day-old leftovers.

The hotel-nightlife world is surprisingly insular. Eric Goode, who started the club Area in the eighties, is partners with Sean MacPherson, who owns seemingly every great bar in Los Angeles. Together, Goode and MacPherson created the Maritime, the Bowery, and the Jane hotels. Balazs, who also owns the Mercer, was an investor in Goode’s seminal late-eighties nightclub, MK, and partnered with MacPherson on Bar Marmont next door to his Chateau Marmont in L.A. Shawn Hausman, Goode’s partner from Area, designed—with the firm Roman and Williams—the interior of the Standard in New York. And Schrager, Balazs, Goode, and MacPherson all share Richard Born and Ira Drukier as business partners. “All of those guys are maniacs,” says Born. “It’s a matter of style, design, and art taking precedence over physical constraints and money. I once described André by saying, ‘If he was drowning, and you threw him a life preserver, he’d catch it, look at it, look up at you, and say, ‘Do you have this in baby blue?’ ”

Though these hoteliers are friendly rivals, they are rivals nonetheless. Sean MacPherson, a tall long-haired fellow with a mellow surfer-dude mien, is sitting on a giant couch in the ballroom of the Jane hotel. “This particular room, literally every piece of furniture, every single pillow, I bought myself. These other hotels, they hire designers and the designer makes a package and they are really selling a product. Here, the product in many ways is us—our taste. The Standard is great, but in the end, it’s like a corporate hotel.”

His partner Eric Goode agrees. “What interests me more and more is to not try to be the most innovative in a gratuitous way,” says Goode. “The Standard in Hollywood, when you check in, they have that sort of Area-like vignette behind the front desk with someone sleeping behind glass. An actual person. And, you know, it’s cute and everything, but the truth is when you check into a hotel, you really want to be left alone and you want to be comfortable because you’ve been traveling for hours.”

Both MacPherson and Goode seem to be pursuing a sort of eighties New York nostalgia in their projects. The Jane, which is MacPherson’s domain in a partnership that Goode qualifies as “a little dysfunctional” after ten years, feels a bit like the Chelsea Hotel without the art, history, or crazy people. “There’s really nowhere downtown that has that eighties gritty New York sensibility,” says MacPherson, describing the hotel, a former flophouse with tiny rooms that go for $100 a night, as a rock-and-roll Royal Tenenbaums meets Barton Fink. “If you are a 19-year-old runaway,” he says, very genuinely, “we want to be your hotel.”

The Bowery Hotel, on the other hand, took more of a “faux-old-world direction,” according to Goode. “It’s not the most inventive thing to do, and we struggled with it. At one point, we wanted to make it a very modern—a Japanese hotel. But this won out. Maybe it was the comfort of knowing that this kind of thing—the comfort of the old shoe—works.”

Tall, handsome, and rumpled-preppy, Goode has a kind of genial world-weariness that comes from having seen more than one generation of young and excited New Yorkers come through the nightlife system. One afternoon over coffee at Gemma, the restaurant at the Bowery Hotel, he bemoans the current state of nightlife. “When I was in nightclubs, I thought they were a really important way for young people who come to New York to meet people and connect,” he says. “Not to be too nostalgic and it-was-only-good-back-then, but I do think there was a difference in the eighties, when nightclubs were more integrated pre-aids and even shortly after that, when everything, black and white, gay and straight, seemed to be more blended together. I can only imagine there still have to be nightclubs where 21-year-olds go. Because this place is expensive for that bracket. If hotels are replacing nightclubs, then they’re replacing nightclubs for yuppies.”

Both Goode and MacPherson were sorely tempted to put a nightclub on the second floor of the Bowery Hotel, but they resisted. “I don’t want to come across sounding virtuous and hollow,” says MacPherson, “but the Bowery Hotel was designed to be a notch more adult than our other properties. I actually pleaded with all the partners: Give me an opportunity to not turn this into a nightclub. I didn’t want a hotel that felt like when you checked in, you were checking in to a nightclub. That’s why there is no music in the lobby and yet it’s always packed.”

But the Bowery Hotel lobby is, in fact, run like an exclusive club—like Nell’s without the dance floor. It can be very difficult to get into. “I get calls still from people who try to come sit in the lobby,” says Goode. “They will text me and say ‘This guy won’t let me sit down.’ ”

With or without an official nightclub, the experience that these hotels offer is essentially about human contact. “It’s the single thing that can’t be duplicated on the Internet,” says MacPherson. “Social networking tries to, but it’s not the same thing. You can get your music, all your entertainment on the Net, but you cannot get lucky except in the flesh.”

Ian Schrager is sitting at a huge wooden conference table in his office in the West Village, surrounded by piles of tear sheets from magazines: bits of design inspiration. It has been 25 years since he kicked off the whole hip-boutique-nightlife-hotel phenomenon. “When I go to a hotel and I want to go to the best restaurant in town,” he says, “doesn’t it make sense to say, ‘Well, it’s right downstairs in the lobby’? And when I want to go to the coolest bar in town, I don’t want to go to where the people from Wisconsin go; I want to go where the people who live in that city go. When you are visiting one of these hotels, you are visiting the city that is manifested in the hotel, that’s encapsulated in the hotel, and that’s the whole point of it. That is what hotels were intended to be until they got grabbed up by these major corporations and they started rolling out cookie-cutter rooms.”

All of the other hoteliers tip their hats to Schrager for pulling hotels out of those beige, boxy doldrums. “I like Ian,” says Goode. “He’s like the guy in Spinal Tap. It goes to eleven. He’s talking about the fact that the thing he opens is going to be a seven-star hotel. There are no seven stars.” He laughs. “Ian is the father of this style.” (And then, with a little bit of an edge to his voice, he adds, “Not André.”)

But Schrager is now rejecting the very aesthetic he created. “The risk is that these unique hotels that we did become the rule rather than the exception,” he says. “You can’t have design on steroids anymore because everybody’s doing it. You’ve got to come from a different place.”

To that end, Schrager has gone into partnership with J. W. Marriott Jr. to create a chain of 100 super-luxury hotels—a “private label” of sorts—that will no doubt go to eleven. He wouldn’t reveal much about the specifics of his plans other than to say that the hotels will be designed by prestigious architects, be modest in size (150 to 200 rooms), and “manifest the social fabric of the cities” they are in. “I’m doing things in a more easy, casual, but incredibly stylish way that really doesn’t have anything to do with design but has a completely classic vocabulary.” He sighs. “There has to be a shakeout.” Yes, but old nightlife habits die hard. Don’t be surprised if some of these super-luxury hotels manifest an unhinged party scene by the pool.

The Hosts of the

All-Night Party

André Balazs

The Standard, the Mercer, Chateau Marmont

Ian Schrager

Morgans, Paramount, Royalton, Hudson, Gramercy Park Hotel

Michael Achenbaum

Hotel Gansevoort, Gansevoort Park Avenue

Eric Goode

and

Sean MacPherson

The Bowery, the Jane, the Maritime, Lafayette House

Photographs by Patrick McMullan