I first remember hearing the Y-word in ’83, when I was living in the East Village, sharing an apartment with my best friend while working on my first novel and paying the bills as a slush-pile reader at Random House. I was enjoying a hung-over midday breakfast (we didn’t use the word brunch in the East Village; it was breakfast whenever you woke up) at Veselka on Second Avenue. My former breakfast spot, the Binibon, had recently been shuttered, having never recovered after Jack Henry Abbott stabbed waiter-playwright Richard Adan outside, on the sidewalk. An ostentatiously besplattered painter I used to see around the neighborhood was sitting next to me at the counter, and I heard him mutter, “Fucking yuppies.” I looked up to see a young couple I myself would have characterized as “preppy” waiting to be seated. They looked as if they were visiting from the Upper East Side—all chinos and oxford cloth. We were all uniformly nonconformist in our black jeans and our black Ramones and Television T-shirts. As a Williams alum, I knew all about preppies even before they’d gone mainstream with the publication of The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980. My younger brother, a Deerfield senior, was a preppy. Many of my classmates were preppies. But this yuppie thing was new to me.

The term probably first appeared in print in 1983, when columnist Bob Greene wrote a piece about former Yippie leader Jerry Rubin, who was hosting “networking” events at Studio 54. Greene quoted a participant as saying that Rubin had gone from being the leader of the Yippies to the leader of the yuppies. The neologism stood for Young Urban Professionals and might have gone down in history as yups if not for the Rubin connection. The term yuppies suggested a certain evolutionary—or devolutionary—trajectory from the hippie and the Yippie. The story had everything—the double irony of the revolutionary trickster turned entrepreneurial capitalist cheerleader and the setting in the glam palace of mindless hedonism, as well as a zippy catchphrase that actually seemed to describe an instantly recognizable new minority. Once we had a name for them, we suddenly realized that they were everywhere, like the pod people of Invasion of the Body Snatchers—especially here in New York, the urbanest place of all. We might have even recognized them as us.

Not long after my first actual sighting, I would see the earliest DIE YUPPIE SCUM graffiti around the neighborhood, an epithet that was soon vying in popularity with that LES perennial EAT THE RICH. The vituperative tone with which the Y-word was pronounced on East Fifth Street was in part a function of rapidly escalating real-estate prices in the East Village; after decades of relative stability that had made the area a bastion of Eastern European immigrants and young bohemians, though, it’s easy to forget at this distance that it was also a war zone where muggings and rapes weren’t considered news. The Hells Angels ruled East Third Street, and after dark you went east of Second Avenue strictly at your own risk. The cops didn’t go there. East Tenth beyond Avenue A was a narcotics supermarket where preteen runners scampered in and out of bombed-out tenements. In fact, great swatches of the city were dirty and crime-ridden. Even the West Village was pretty gritty by today’s standards, and Times Square was a scene of spectacular squalor. Check out Taxi Driver or The French Connection if you want to get a sense of what this urban wasteland looked like.

It wasn’t just the way the city looked, though. New York was, on the whole, a much more parochial place back then, much more divided along ethnic and class lines. Little Italy was still mostly Italian, the East Village heavily Ukrainian. Wealthy Wasps still clustered on the Upper East Side, west of Third Avenue, and Harlem, of course, was 99 percent black, and many white people lived in mortal terror of nodding off on the subway and waking up at 145th Street. The white middle class was draining away from the city, heroin was epidemic, and crime rampant. When I first moved here, getting mugged was a rite of passage. Both of my first two apartments were broken into, and the 1966 Volkswagen my parents bought me for graduation was stolen not once but twice. This was pre-yuppie Manhattan, a city, dare I say it, in desperate need of gentrification.

In the latter half of the seventies, it was a semi-serious idea that the city would be abandoned by the affluent, the young, and the fleet, left to the poor and the halt and the aged. But sometime after the election of Ronald Reagan, in 1980, it became clear that New York had pulled up its socks and reversed the fiscal, physical, and psychic dilapidation of the seventies. The stock market began a steady ascent, which created new jobs on Wall Street. At some point, the influx of ambitious young strivers started to exceed the exodus, and while many of them gravitated toward the traditionally bourgeois neighborhoods of the Upper East Side, others began to reclaim the housing stock of previously marginal or downright dangerous areas like upper Amsterdam and Columbus, or to colonize old factory buildings in nonresidential neighborhoods like Soho and Tribeca and the East Village. When artists did this, it was called homesteading. When people whose day jobs required them to wear leather shoes (yuppies) followed the artists, it was called gentrification.

In my old neighborhood, the renovation of a formerly grand, long-derelict building called the Cristadora, located on the east side of Tompkins Square Park, was one of the flash points of the war against gentrification, a.k.a. yuppification. The Cristadora became the target of protests and riots, with greedy real-estate developers and their yuppie clients cast in the role of villains. The fact that Malcolm McLaren and Iggy Pop eventually became residents kind of muddied the stereotype. Was Iggy a yuppie? McLaren maybe. These were the ethical and nomenclatural dilemmas we faced, as New York changed around us and we all started to make more money and buy espresso machines.

The East Village art scene, which started with the opening of Patti Astor’s Fun Gallery in 1981, had really taken off by the end of ’83, the galleries increasingly drawing the kind of well-heeled crowds that the creators of the scene despised. The yuppies, once they were identified, incarnated an internal contradiction of the art world that we now take almost for granted: The bourgeoisie themselves are the end consumers of all épater la bourgeoisie production. Basquiat wasn’t selling $50,000 canvases to his fellow junkies.

From the beginning, there was a certain subject/object confusion associated with the yuppie concept, a certain “we have met the enemy and he is us” self-reflexivity to the phenomenon. Downtown mohawked squatters aside, it was sometimes hard to find a Manhattanite without some taint of the new lifestyle. Did gym membership qualify you as a yuppie? Snorting coke? Eating raw fish? When I heard a movie agent slinging the term at a group of bankers at the Odeon, I wondered about pots and kettles.

It’s hard to believe, but there weren’t all that many gyms in Manhattan in 1979.

Nationally, the ground had been prepared by the election of Ronald Reagan, the former actor with the Colgate smile, and his imperious wife, Nancy. Mrs. Reagan spent $25,000 on her inauguration wardrobe, and a planned redecoration of the White House family quarters was to cost $800,000. Apparently, that was a lot back then, judging by the breathless tone in which the figure was quoted. The price tag for the White House china was $209,508, which still seems like a lot. Luxury! After years of Jimmy Carter empathizing with our malaise and telling us to lower our expectations and carry our own suitcases, the Reagans were unself-conscious advocates of the good life. Conspicuous consumption was good. It was morning in America, according to Reagan, which seemed to mean that the sixties were finally over.

We didn’t know it at the time, but the birth of the new species might be pegged to the September 22, 1982, debut of Family Ties and the first appearance of Michael J. Fox as Alex Keaton, the briefcase-toting young Republican. In retrospect, it seems clear that Keaton was the proto-yuppie. The spawn of hippie parents, born in Africa while they were working for the Peace Corps, he wears a tie around the house, worships wealth, business success, and Ronald Reagan, and aspires to a career on Wall Street. The show ran for seven seasons, from ’82 to ’89, and illustrated a strange cultural inversion whereby a conservative younger generation cast aside the liberal values of their parents. The creators had envisioned a sitcom focused on the parents, but the young Republican soon stole the show. If at first he seemed an anomaly, he soon came to seem like an avatar of the Zeitgeist.

“Who are all those upwardly mobile folk with designer water, running shoes, pickled parquet floors, and $450,000 condos in semi-slum buildings?” asked Time magazine in its January 9, 1984, issue. “Yuppies,” we were informed, “are dedicated to the twin goals of making piles of money and achieving perfection through physical fitness and therapy.” The Yuppie Handbook, which had just been published, defined its subject: “(hot new name for Young Urban Professional): A person of either sex who meets the following criteria: (1) resides in or near one of the major cities; (2) claims to be between the ages of 25 and 45; (3) lives on aspirations of glory, prestige, recognition, fame, social status, power, money, or any and all combinations of the above; (4) anyone who brunches on the weekends or works out after work.”

Apparently, the creatures anatomized in The Yuppie Handbook were just common enough to elicit recognition, but not so general as to provoke a shrug. The concepts of “brunching” and “working out” were apparently new and humorous. A few of their defining characteristics—dhurrie rugs, potted ferns, pickled parquet floors—sound suitably dated. But many more—European automobiles, gourmet kitchens, computer literacy, designer clothing, and sushi—fail 25 years later to convey the exoticism that the authors seem to have intended. Oh, those wacky yuppies, eating raw fish and going to the gym.

Perhaps the ultimate symbol of the yuppie era, not mentioned in the book, was the Baby Jogger. In a 2003 valedictory to the yuppie, Tom McGrath lauds “the glistening spoke-wheeled stroller that made its debut in the eighties. So many elements of yuppiness were present all at once in the Baby Jogger: quality time with your child, exercise, and a technologically advanced, ridiculously expensive thing everyone else could admire.”

Like hippies, yuppies were baby-boomers rebelling against their parents. But the yuppies weren’t rejecting their parents’ politics so much as their parents’ taste and budgetary constraints. Yuppies seemed to be apolitical. Urbanity, one of their namesake characteristics, was a reaction to the suburbs, where many of them had grown up. Their epicureanism was presumably a reaction to the canned, frozen, and processed food that most of them had grown up on. As for their signature ambition, well, BMWs and 5,000-square-foot raw loft spaces didn’t come cheap, even in 1984. But of course there was more to it than that, even in the cartoon version, since the self-improvement ethic extended to the physical realm as well. It’s hard to believe now, but there weren’t all that many gyms in Manhattan in 1979.

My first novel, Bright Lights, Big City, came out in September 1984, although it was set a few years earlier, in a grubbier, less prosperous New York. No one was more surprised than me when The Wall Street Journal described me as a spokesman for the yuppies. The protagonist of the novel was a downwardly mobile fact-checker and aspiring novelist, and unless I’m mistaken, he didn’t eat any raw fish in the novel. His best friend, Tad Allagash, was a likelier yuppie, an adman with entrée to all the right places, an uptown boy who knew his way around downtown. And they both did a lot of coke, a.k.a. Bolivian Marching Powder, which was to become the emblematic drug of the eighties, what acid had been to the sixties.

For a brief period, coke seemed like the perfect drug for bright, shiny overachievers. We knew that heroin was hopelessly addictive and speed killed, but coke seemed harmless. It helped you stay up all night, and the next day, if you felt a little comedown, it was a far more effective pick-me-up than a double espresso. Not long before the first DIE YUPPIE SCUM graffiti appeared, a friend of mine pointed out an ad in the Village Voice for something called Cocaine Anonymous. This was a source of great mirth for us. It was as if we’d stumbled across an ad for Cash Anonymous or Caviar Anonymous. (Back then, the idea of sex addiction would have sent us into paroxysms of hysteria.) We simply didn’t think it was possible to have too much of this particular good thing. In part, this was a function of limited budgets, my friends being in the arts and publishing. We weren’t buying eight-balls. But even those who were thought they had discovered the secret of perpetual motion. Even when John Belushi died, in 1982, we could tell ourselves that it was the heroin rather than the coke in his speedball that had stopped his heart. The decade would be pretty well advanced before we would notice that it was possible to have too much of a good thing. For some reason we imagined, for a while, that there was no payback. All at once, coke was everywhere: Wall Street, Madison Avenue, Seventh Avenue.

Who do you think Basquiat sold his $50,000 canvases to, his fellow junkies?

Coke was the perfect metaphor for a culture of runaway consumption, for a culture based on credit that believed in an endless postponement of consequences. Cocaine was literally a treadmill; there was no end point at which fulfillment was reached, where the exact right number of lines had been consumed. Fulfillment was always one line away. And eventually many of us learned that what went up must eventually come down, a lesson that was brought home on October 19, 1987, when the stock market came crashing down after a long and exhilarating bull run.

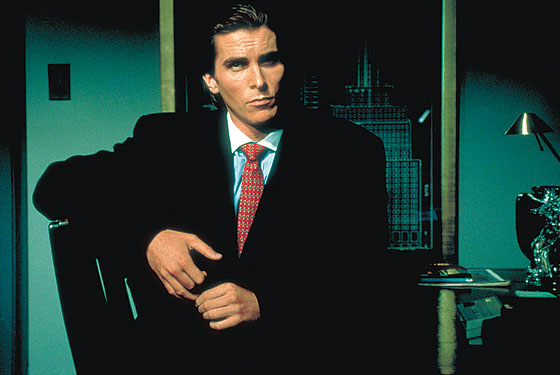

A few months after Black Monday, Newsweek declared the yuppie extinct, and various commentators have been writing obituaries ever since, the most powerful of which was a novel called American Psycho, published in 1991 by Bret Easton Ellis. Ellis’s send-up of the materialism of the era is exhaustive to the point of feeling almost definitive. Patrick Bateman is the Über-yuppie whose hobbies just happen to include torture and murder. His taste is impeccable, and taste was the hallmark of the species. If someone asks, as my son did recently, “What is a yuppie?,” we need only point to Bateman:

“I worked out heavily at the gym after leaving the office today but the tension has returned, so I do 90 abdominal crunches, 150 push-ups, and then I run in place for twenty minutes while listening to the new Huey Lewis CD. I take a hot shower and afterwards use a new facial scrub by Caswell-Massey and a body wash by Greune, then a body moisturizer by Lubriderm and a Neutrogena facial cream. I debate between two outfits. One is a wool-crêpe suit by Bill Robinson I bought at Saks with this cotton jacquard shirt from Charivari and an Armani tie. Or a wool and cashmere sport coat with blue plaid, a cotton shirt and pleated wool trousers by Alexander Julian, with a polka-dot silk tie by Bill Blass.”

In Patrick Bateman, Ellis created the grown-up evil twin of Alex Keaton, a man for whom an Armani suit has more reality than the human being within it. Mergers and acquisitions? Murders and executions? Easily confused, as are Patrick’s nearly interchangeable friends, lovers, colleagues, and victims.

As much as the term conjures the eighties, the yuppie has never quite faded into history. In 2000, David Brooks tried to refine the concept, coining the term BoBo to describe an allegedly more enlightened consumer who combined the self-interest of the eighties with the liberal idealism of an earlier era, using the Y-word to denote a less enlightened group. In the meantime, the yuppie family tree has thrown off another branch, the hipster. Hipsters believed they were the ultimate anti-yuppies. Unlike their forebears, they wanted to be known not by their job or ambition but by their self-conscious disregard for either. If anything, the cult of connoisseurship was even more exaggerated in this subgroup. Their code, enshrined in Robert Lanham’s hyperironic 2003 Hipster Handbook, was inherently elitist, defining itself in opposition to the mainstream. Hipster consumerism championed the notions of alternative and independent, rejecting the yuppie embrace of certain consumer brands in favor of their own. So it was vintage T-shirts rather than Turnbull & Asser dress shirts with spread collars, Pabst Blue Ribbon over Chardonnay. But ultimately, whether you love Starbucks or loathe it, a world in which we are defined by our choice of blue jeans and coffee beans owes more to Alex Keaton than to Abbie Hoffman.

And as if to prove that the hipster and the yuppie are brothers under the skin, borough-bred columnists like Denis Hamill and Jimmy Breslin still find the yuppie label useful for bashing a certain breed of interloping effete New Yorker, the kinds of people who may in fact identify themselves as hipsters.

There probably are a few Budweiser-drinking union members left out in Brooklyn and Queens who guffaw at the idea of anyone belonging to a gym or buying coffee at any place other than a deli, but generally speaking, yuppie culture has become the culture, if not in reality, then aspirationally. The pods have pretty much taken over the world. The ideal of connoisseurship, the worship of brand names and designer labels, the pursuit of physical perfection through exercise and surgery—do these sound like the quaint habits of an extinct clan?