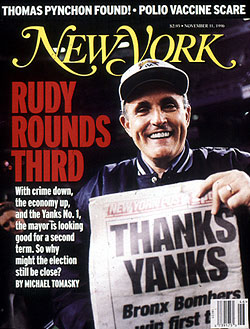

From the November 11, 1996 issue of New York Magazine.

Thomas Pynchon leaves his Manhattan apartment building; he’s wearing a pair of jeans and comfortable shoes. He, of course, looks much older than his pictures; the last one anybody has ever seen was taken in 1955, when he was in the Navy. He’ll be 60 next year, and his hair has gone gray. He keeps it long, and has a white mustache and beard. It appears that his famous snaggle of teeth has been fixed. He wears glasses. His eyes, shadowed in dark in those few early photographs, are blue. Thomas Pynchon walks down a New York City street in the middle of the morning. He has a light gait. He floats along. He looks canny and whimsical, like he’d be fun to talk to; but, of course, he’s not talking. It’s a drizzling day, and the writer doesn’t have an umbrella. He’s carrying his own shopping bag, a canvas tote like one of those giveaways from public radio. He makes a quick stop in a health-food store, buys some health foods. He leaves the store, but just outside, as if something had just occurred to him, he turns around slowly and walks to the window. Then, he peers in, frankly observing the person who may be observing him. It’s raining harder now. He hurries home. For the past half-dozen years, Thomas Pynchon, the most famous literary recluse of our time, has been living openly in a city of 8 million people and going unnoticed, like the rest of us.

Ask people in Pynchon’s own neighborhood where they think he might be hiding out, and you get a variety of responses: “He lives in Mexico,” says a clerk in a bookstore a few blocks from his building.

“Out west somewhere,” says a salesperson in a gourmet-coffee store around the corner.

“He’s disappeared, and no one will ever find him, because that’s how he wants it,” says a man walking past the entrance to Pynchon’s apartment building.

Since 1963, when Pynchon’s first novel, V., came out, the writer—widely considered America’s most important novelist since World War II—has become an almost mythical figure, a kind of cross between the Nutty Professor (Jerry Lewis’s) and Caine in Kung Fu. There has never been a confirmed Pynchon sighting published before this one, but there have been plenty of wild theories about his whereabouts, advanced by gonzo fans and serious scholars. People have said that Thomas Pynchon is “really” J. D. Salinger; that he travels around by bus, crisscrossing the country and leaving little clues as to his identity; that he’s posed as a literary-minded bag lady who writes letters to an obscure Northern California newspaper (there’s a new book out about that, The Letters of Wanda Tinasky). There was even a rumor, hotly debated on the Pynchon Websites on the Internet, that Thomas Pynchon was the Unabomber. Pynchon showed up at an apple-picking fest in Northern California, calling himself Tom Pinecone; Pynchon was walking the Mason-Dixon line, researching his next book, said to be a “big one” (it’s coming out, finally, in the spring of 1997, according to Pynchon’s editor at Henry Holt). Sal Ivone, managing editor of Weekly World News—the tabloid that told the world that “Elvis is alive”—reports, “In the first week of October, Weekly World News recorded three Elvis sightings, two Bat Boy sightings, one Bigfoot encounter, and, amazingly, one for Thomas Pynchon. We haven’t checked it out because it sounds too far-fetched to us.”

In the seventies, after the startlingly brilliant and difficult Gravity’s Rainbow—perhaps the least-read must-read in American history—came screaming across the landscape, Pynchon was hot, in mediagenic terms, and a virtual subgenre of New Journalism sprang up and circled around trying to find him, or at least understand him as a literary MIA. ” ‘My quest for Thomas Pynchon,’ ” says David Streitfeld, book critic for the Washington Post, “was fourteen gallons of indulgence: ‘I started on my quest for Thomas Pynchon, and I found myself.’ “

In 1990, when Pynchon’s last novel, Vineland, appeared, there was again a spate of articles speculating on the location of the so-called Invisible Man. THOMAS PYNCHON, COME OUT, COME OUT, WHEREVER YOU ARE, shouted one magazine headline. People magazine called Pynchon’s address “the best-kept secret in publishing.”

On an openly accessible online service that uses a cross-referencing of credit-card and telephone numbers, New York discovered Thomas Pynchon’s address in about ten minutes. “We have recently moved,” Pynchon noted in his introduction to Slow Learner, a book of early short stories, “into an era when … everybody can share an inconceivably enormous amount of information, just by stroking a few keys on a terminal.”

With just a few keystrokes, New York was able to learn that Pynchon’s neighborhood is a bustling, civil, and prosperous one, with good subway access. In the vicinity of his building, there’s a discount department store, a bagel shop, a church. At the corner, a man with a fruit-and-vegetable stand sells broccoli and bananas.

The building itself is stately, if gritty. It could use a sandblasting. A rumpled doorman sits on a folding chair by the entrance, watching the people outside pass. Pynchon’s neighbors are of various ages, races, states of fashion-consciousness. There’s a man who comes and goes expertly in a motorized wheelchair. The neighborhood is New York at its finest: tolerant, navigable, sane. It’s the New York that could almost lull one into believing that broader American myth, the one Pynchon warns against in his fiction: All is right with the world.

In Pynchon’s world, there are protectors, people who attempt to create a ring of fire around what is, ultimately, a banal secret: He’s here, and aside, perhaps, from what’s going on in his brain, he seems to lead an unremarkable life—or at least the life of any number of New York’s literary gentlemen of a certain age. But knowing Thomas Pynchon, or even knowing of him, has taken on a talismanic resonance with a particular sort of crowd (“There are people out there from the New Yorker magazine!” quoth Woody Allen’s wife in Annie Hall, in a similar mood). Questions from reporters can lead to an instantaneous defensiveness on behalf of the author.

“I’m not going to talk about this man,” says Ray Roberts, Pynchon’s editor at Henry Holt.

“I cannot speak about this matter,” says literary critic Harold Bloom. (There’s a story that Bloom and his buddies at Cornell once inducted young Pynchon into their alternative fraternity, Yud-Yud-Yud, also known as Tri-Yud or Gefilte Phi.)

“If he hasn’t asked for publicity, then he doesn’t deserve it,” says David Streitfeld, who nevertheless fingered Newsweek columnist Joe Klein as the anonymous author of Primary Colors on page 1 of the Washington Post. “Joe Klein,” he says, “was a different issue.”

Phil Patton, a writer for Esquire who admits to being Pynchon’s friend, wouldn’t comment on the fellow, either. It’s not that he was ever asked not to. “It’s unclear how it got started,” he says. “I’ve never had anyone discuss it with me. There’s no grand conspiracy.”

“He’s disappeared, and no one will ever find him, because that’s how he wants it,” says a man walking past the entrance to Pynchon’s building.

Still, it’s an amazing feat for Pynchon to have maintained his privacy in this big, buzzing city, where gossip has 747 wings. It makes you think there’s more behind the silence than just the ultimate insider cachet of being “down” with the quintessential mystery man. “The only thing I can guess is that those who meet him like him,” ventures Paul Gray, book critic for Time. “They know that if they go running to “Page Six,” they probably won’t get to see him anymore.”

There are, however, stories, always told anonymously (for their own protection, the tellers say, against the wrath of the Pynchon protectors) and with a sense of astonishment as to their sheer mundanity. As it turns out, the truth about Thomas Pynchon is much less strange than his fiction:

“Someone was telling me he went on a picnic with Pynchon and his wife and kid,” says one magazine writer who lives here. “He said, ‘We walked around’—whatever. It was ‘In the Suburbs With Thomas Pynchon.’ “

“He was at a Sag Harbor literary party several years ago,” says another writer. “He seems like a normal guy.”

“Somebody I know was at a dinner party with him. Susan Sontag was there too,” says a magazine editor. “He was seen at an outdoor café having lunch with Don DeLillo,” another writer says.

“They [Pynchon and his wife] don’t go out a lot,” says a literary agent. “They’re like a regular couple.”

“It may be easier to be private than anyone thinks,” Patton says.

New York may in fact be the perfect place for Thomas Pynchon, the city where he was meant to live all along. Pynchon started out in New York, or in the environs, and in a sense he has come full circle. He was born in Glen Cove, Long Island, the son of a superintendent of highways for Oyster Bay. (Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Sr. died last year, and Pynchon is said to have attended the funeral.)

At 16, Pynchon went to Cornell, where, classmate Jules Siegel recalled in Playboy in 1977, he was “quiet and neat” and “did his homework faithfully.” “He went to Mass and confessed, though to what would be a mystery.”

From 1955 to 1957, Pynchon served in the Navy and was assigned to the Sixth Fleet, which patrols the Mediterranean. There he became acquainted with Malta, which served as a backdrop for V. “It’s not known why he left school and joined the Navy,” says John Krafft, co-editor of Pynchon Notes. “He wanted to see the world? He had an unhappy love affair?”

After graduating from Cornell in 1958 with a degree in English (he had started out in engineering physics), Pynchon was back in New York City, doing the beatnik thing. “Like others,” Pynchon writes in Slow Learner, “I spent a lot of time in jazz clubs … I put on hornrimmed sunglasses at night. I went to parties in lofts where girls wore strange attire.”

In 1959, Pynchon was awarded a fellowship to do graduate work at Cornell but passed it up. Instead, he got a job as a technical writer for Boeing in Seattle, writing V. in his free time. After that, he took off for Mexico. “There seems to have been the feeling that if he didn’t start writing seriously, he was never going to do it,” says Stephen Tomaske, a librarian at the University of California at Los Angeles and a dedicated Pynchon tracker.

Then in 1963 came a Faulkner Award, and then, that same year, the primal scene spawning Pynchon’s reputation as a recluse. When Time magazine sent a photographer to Mexico City to take his picture, he supposedly hopped a bus headed into the mountains. An overgrown mustache he was wearing at the time fanned the legend that the locals took to calling him “Pancho Villa.”

But if Pynchon has engaged in a life of actual chase scenes, it hasn’t shown up—contrary to legend—in his addresses. He seems to have occupied only a handful of relatively long-term residences since the sixties: a couple in Berkeley; one in Manhattan Beach, California (where he wrote The Crying of Lot 49); one in Aptos, California (where he wrote much of Vineland). Through it all, he has maintained a quiet connection to the East Coast and to New York City, returning regularly to visit friends and check out the music scene. “He’s a bicoastal kind of guy,” Tomaske says.

Love brought Pynchon back to New York this time around, apparently. His wife, literary agent Melanie Jackson, worked here. They now have a small boy, Jackson, who attends a private school.

It’s rumored Pynchon will do a book tour. “What would they do,” asks a writer. “Put a bag over his head like he’s in the witness-protection program?”

“At the beginning, he never declared his anonymity,” says Edward Mendelson, a leading Pynchon critic. “It just grew.”

Despite the continual tries of news outfits, Pynchon never granted an interview or agreed to have his picture taken. He never did Carson; he hasn’t even done the 92nd Street Y. In 1974, when he won the National Book Award for Gravity’s Rainbow, Pynchon sent comedian and self-billed “expert on everything” Professor Irwin Corey to accept the prize on his behalf. Corey delivered a speech that was described by the New York Times as “a series of bad jokes and mangled syntax which left some people roaring with laughter and others perplexed.”

“There’s some circumstantial evidence,” says Tomaske, “that Pynchon felt a growing dissatisfaction with the idea of the writer as celebrity. If Norman Mailer or Truman Capote picked up a pen, it had become news. And it struck Pynchon as unseemly.”

“He is not at all disingenuous about it like Woody Allen, who says he’s shy but then can be found at Elaine’s with the Rolls-Royce parked outside,” says literary agent Chris Calhoun.

There is also the possibility, however, that Pynchon split because he was concerned about the consequences of the political messages in his novels. He came of age during the McCarthy hearings, and the year V. was published, John F. Kennedy was shot. “Pynchon writes in a kind of code about the increasing role of government in subjugating the individual to the state,” says Charles Hollander, an independent Pynchon scholar in Baltimore. “He and his writing are both camouflaged because he fears the power of the state.”

“What are you always so afraid of?” Jules Siegel says he once asked his Cornell classmate; he had sensed a growing anxiety in Pynchon about what could be viewed as anti-Establishment ideas. “Don’t you understand that what you have written will get you out of almost anything you can get yourself into?” But at the time, Pynchon was apparently unwilling to accept the idea that the power of celebrity could act as a safeguard against the government. (This was pre-O.J.)

Footsteps behind him. On passing the next street lamp, he saw the elongated shadow of helmeted heads bobbing about his quickening feet. Guardie? He nearly panicked: he’d been followed… .

“Go to hell,” he said cheerfully.

—from V.

What more fitting a place to deliver those choice words than, again, New York City? “There’s an old Russian saying,” offers writer Andrew Solomon, “that if you want to hide from the authorities, stand underneath the brightest light, closest to the police station.”

Ironically, Pynchon’s refusal to assume a public persona has only fueled an image he may have never intended. “It works for him that he is a recluse,” says Chris Calhoun. “I’m sure this is a coincidence, but it’s very big business.”

“In choosing to remain invisible,” says Gray, “he has made himself far more intriguing than the novelists you can watch on the Today show.”

Lately, however, things have been changing. Pynchon hasn’t done Rolonda yet, but he has done some print, some TV, and some rock and roll. “He doesn’t seem as concerned with being a recluse recently,” Tomaske says a bit worriedly.

It must have elicited a double take from most everybody opening The New York Times Book Review on June 6, 1993, that Thomas Pynchon had written a long essay on one of the seven deadly sins—sloth. (A self-mocking choice on his part, perhaps, since it was well known that it took the writer seventeen years to get from Gravity’s Rainbow to that much lesser book Vineland.) Not only was Pynchon revealing his musings on morality; he was admitting to having flipped through the National Enquirer and noticed who won its national Couch Potato competition.

Then in ‘94 came The John Laroquette Show. Reports that Pynchon vetted a script with a subplot involving him turn out to be perfectly true. “I got a call from Pynchon’s agent,” says Don Reo, then the head writer on the sitcom, “saying Pynchon liked the script, but he wanted a couple of changes. ‘First,’ she said, ‘you call him Tom, and no one ever calls him Tom. Second, although he likes Willy DeVille’ “—of Mink DeVille, of whom Reo had Pynchon giving away a T-shirt to a pal in a diner—” ‘he would prefer if it were a T-shirt with Roky Erickson of the 13th Floor Elevators,’ ” a psychedelic Texas band.

“When we first met him, we were, like, the guy’s weird. And then he said he was Pynchon, and we were, like, yeah, right, anybody could say that.”

Pynchon’s emergence became all but official earlier this year when he wrote the liner notes for the alternative-rock band Lotion and conducted an interview with the four band members in Esquire. Pynchon’s Lotion notes, by the way, are full of remarks that anyone could take as an indication that he lives in New York City. And like most New Yorkers, he sounds on the verge of being fed up with the place, accusing New York of being “in the middle of a seasonal charm deficiency.” Pynchon’s as annoyed by Disney’s seizure of 42nd Street as everybody else in town: “Times Square is being vacated and jackhammered into somebody’s idea of an update… .”

Rob Youngberg, Lotion’s drummer, says he thinks Pynchon’s liner notes are “perfect.” “We wanted him to do them, so we kept hinting… . Then he offered. It was like that awkward moment on the first date.”

The press registered a fair amount of amazement when Pynchon’s buddyship with Lotion became evident. The story, told in The New Yorker and other places, is that Pynchon followed the band to a gig in Cincinnati, where he revealed himself backstage. And they all became friends. Pynchon wore a Godzilla T-shirt. “That is not totally true. I think it was Rodan the flying dinosaur,” Youngberg says.

Some people wonder whether any of it is true, or just Pynchon pulling everybody’s leg again, with the boys in the band in cahoots. “As I understand it, the real story is that the father of one of the band members is Thomas Pynchon’s personal banker,” says a music reporter. “But I can’t prove it.”

Youngberg just laughs at how he and his colleagues have become part of the Lore. “When we first met him we were like, the guy’s weird. And then he said he was Pynchon, and we were like, yeah, right, anybody could say that. Then we found out he was Thomas Pynchon and we said, well, that makes sense.

“He’s not what you would expect,” adds Youngberg. “He’s just really nice and very friendly. He likes the way we write songs; we loved the way he writes books.”

Pynchon’s latest book is, like everything else about him, surrounded by rumors. For nearly twenty years, there has been speculation that he was working on a novel having something to do with the Mason-Dixon line. His publisher, Henry Holt, announced last week a title confirming the conjecture: Mason & Dixon will come out in the spring. According to the Washington Post, the 1,000-page manuscript is “a reimagining of the lives of British surveyors Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon. According to one description, it features Native Americans, frontier folk, ripped bodices, naval warfare, erotic and political conspiracies, and major caffeine abuse.” Sort of Thomas Pynchon-meets-Margaret Mitchell, at Starbucks. “People always have misinformation about his hovels,” says Roberts, Pynchon’s editor. “I doubt even his friends know what this book is about.”

Whatever it’s about, the book figures as a turning point in Pynchon’s reputation. Has the guy still got it? “He started out so magnificently, and then we got that terrible book [Vineland],” says Harold Bloom. “I hope he will vindicate himself with the new one.”

It’s hard to imagine that, whatever the response to his next effort, Pynchon would ever resort to hawking it on a book tour, his recent bout of visibility aside. But strangely enough, Cups magazine, the free café weekly, reported recently that a book tour is just what Pynchon is thinking of doing. ” ‘Maybe I will do a book tour for the next book,’ ” Cups quotes another Holt author, Steve Erickson, quoting Pynchon.

Which brings a little yelp of laughter from Lottchen Shivers, Holt’s marketing director. “Oh, I doubt it,” says Shivers.

It’s irresistible to try and envision, however. “What would they do with him on a book tour—put a bag over his head like he’s in the witness-protection program? Alter his voice so he sounds like Henry Kissinger?” asks one writer.

“You would try to get him on 60 Minutes or 20/20 the night before the book comes out,” muses a publicity director at a major publishing house. “You would do the Times, Time, and Newsweek. I could see him doing a radio interview—maybe ‘Fresh Air’ with Terry Gross.”

“Is this where I’m supposed to say something really cheesy like, ‘We’d put him on the cover, but only if he’d pose with Pamela Anderson Lee?’ ” asks Mark Harris, senior editor at Entertainment Weekly. “We would line up with every other American magazine that covers culture. We’d do a dignified story.”

But there are those who feel that Thomas Pynchon on a book tour would be a debacle. The 10,000 who swarmed Rockefeller Center for Howard Stern’s Private Parts would hardly show up for the man who is, essentially, the anti-Stern. “A book tour would be very ill advised,” one literary agent says. “It’s a very sophisticated thing to be into Pynchon, and the people who are would find a way to be above it all. If you read and understand his books, you wouldn’t want to see him in person.”

And what, really, would be the point of it? “I’m not interested in his high-school photo or if he shops at Zabar’s,” says Jeff Seroy, director of publicity at Farrar, Straus & Giroux. “It doesn’t matter whether he’s sexy or gives good sound bites, or can tell Oprah about his pain. There’s such integrity to him and his work. He’s like what the Japanese call a national living treasure.”

Like the skyline of New York itself—everywhere and nowhere, really. And maybe that’s the way it should be. In his Slow Learner introduction, Pynchon writes of once catching sight of the real-life model for the character Pig Bodine in V.—a man he had never met, but who “had become a legend.”

“It’s pleasant to recall that our paths really did cross,” wrote Pynchon, “in this apparitional way.”