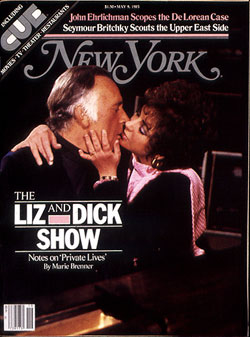

From the May 9, 1983 issue of New York Magazine.

The rehearsal had already dragged on for hours, the air conditioning had long since died, and the stars, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, were beginning to get a bit whiny, complaining about the heat at the Shubert Theatre in Boston, one of the more superficial problems of this production of Private Lives. The day after the first preview, a delicious sense of crisis was in the air, Richard and Elizabeth were running lines each morning at the Ritz, everybody was angry with the director, and the semi-hysteria wasn’t much different from what goes on with any show while it’s out of town. But this wasn’t any show: this was a sideshow, a canny exploitation guaranteed to turn out the crowds—Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton co-starring onstage for the first time.

Such troubles! Taylor and Burton, scarred survivors of tabloids and marital wars, were wheeling their circus into town prior to a ten-week run in New York, and the paparazzi were ready to descend. Bodyguards had been hired, and the cognac diamonds hauled out of the vault. Burton was recovering from back surgery, and Taylor talking about her hematoma from the car crash in Israel. Zev Bufman, her co-producer, was fielding calls from the international press and organizing sawhorses as a barrier against the hordes of fans outside, some of them clutching tattered copies of Kitty Kelley’s The Last Star, hoping for an autograph. The Taylor-Burton coterie of press agents and associates were flying in and flying out, limos were dispatched to Logan airport, everyone was being shifted around in suites at the Copley Plaza, and if that wasn’t enough, just before the first preview the rubber air bags that move the scenery had collapsed. Which meant more experts would be flying in and flying out. The principals didn’t know their movements, were blowing lines, and there remained a very tricky dance sequence in the second act to re-choreograph.

So Richard Burton, suitably grim, was onstage blocking out his own dance steps, moving slowly because of the pains in his spine, his navy jogging suit making him look as thin as the playbill. His second and third wife, Elizabeth Taylor, was slaving, too, going over and over a bit with the Victrola.

“All right, darling, let’s do,” Burton said, and off they glided, reincarnated as those 1930s lovers Elyot and Amanda, Noel Coward’s ex-husband and ex-wife who have just abandoned their new spouses and are trying to make a go of it again. And so the waltz began, tentatively, as they navigated the steps of their Paris living room, trying to avoid the Braque reproduction and the grand piano. Taylor was wearing high heels, cuffed jeans, and a silky sweatshirt, and as she tried to keep her eyes fixed on her partner, their feet and dialogue got tangled, and they stumbled over Coward’s precious quips until, dance over, they collapsed on the divan.

“Darling,” Elizabeth Taylor said to Richard Burton, “you’re still wearing your wedding band.” She took his hand tenderly. “I know,” Burton said. “Why don’t you take it off?” Taylor said. “Because I can’t get it off.” “I see,” she said, light as a meringue. The moment played like Noel Coward, deft, a little too fraught with meaning, except, irony of ironies, it wasn’t from Private Lives at all.

The Taylor-Burtons arrived last week for a limited run. Elizabeth Taylor, tired of doing General Hospital and not ready to become Mrs. Victor Luna, is eager for another Broadway triumph. Private Lives is not a showpiece, like The Little Foxes, but Taylor says, “I am ready for Nouveau York.” Rock Hudson—“one of my best friends”—has lent her his apartment. “I guess that means when he comes in for the opening I’ll have to offer to get him a hotel room,” she says. Those nasty questions about the dignity of trotting out the linen of her own private lives don’t bother Elizabeth Taylor Hilton Wilding Todd Fisher Burton Burton Warner, overchonicled, overquestioned, overplayed. “Who cares,” she said in her dressing room up in Boston. “For heaven’s sake, it just adds a giggle to the whole thing. At this point, I know who I am and what I am.”

The Boston run was sold out, but there was a savage pan by Kevin Kelly in the Globe. “He review really cheesed me off,” Taylor said, “because it was like a personal vendetta.” Burton was characteristically aloof. “I’m an old war-horse,” he said. “I don’t even read the damned things.” Elizabeth Taylor had larger things to think about. So far, the New York theater has sold only two-thirds of the house. In Boston, the production looked pretty creaky, but the onstage contretemps were trifling compared with what was happening off.

Zev Bufman, 52, the co-producer, knows he is a very lucky man, so he is not reticent with his biographical details. His father owned two movie theaters in Tel Aviv, and Bufman’s one distinction growing up with his brilliant imitation of the Danny Kaye routines he’d repeatedly seen. That arcane talent got him to America to tryout for a production of Lady in the Dark. His performance of the rapid-fire “Tschaikowsky” (“There’s Malechevsky, Rubenstein, Arensky, and Tschaikowsky…”) launched him into show business. In 1980, he was in Washington trying to get a revival of Brigadoon off the ground. By that time, he had given up acting for producing, and his fortune had been made primarily by a few theaters he owned in Florida. Although the label “Zev Bufman Presents” has never implied the National Theatre of Great Britain, Bufman was doing very well.

So on opening night of Brigadoon, his date was the founder of Wolf Trap, Kay Shouse, who told him, “I’ve invited a good friend of mine, a senator’s wife, to join us. She is terribly bored here and has nothing to do.” “Fine,” Bufman said, his mind on the first act. But the senator’s wife was late, very late. As the overture ended, Bufman heard the sound of feet running down the aisle, and “then somebody slammed me on the shoulder very hard, like ‘Move over,’” but he didn’t turn around to see who it was. When he finally did look, “the first thing I saw were those two violet eyes, and I stammered, ‘My name is Z-z-z…’ To this day Elizabeth calls me ‘Z-booby.’”

“Hold my hand very fast, I’ve got to run to the bathroom” was the first remark Mrs. John Warner made to her future partner. That was, as Bufman put it, “lesson number one.” Mrs. Warner was earthy, didn’t stand on ceremony, and knew how to beat the crowd. Bufman was not so bad at beating the crowd, either. After the party that night, he turned to Elizabeth Taylor and said, “How about doing a Broadway show with me?” and she answered, “I’d love to.” “I felt there had been a spark between us,” Bufman said.

Lesson two came a few weeks later, in New York, when the new best friends decided to take in 42nd Street. There were no tickets until Bufman said the magic word: “I’m bringing Elizabeth Taylor.” “That was my second lesson. Never say you’re bringing her anywhere.” They arrived at the Winter Garden, and so did 200 photographers, who pushed past the ticket taker, shoving Elizabeth, almost giving her a black eye. For a few moments, Bufman thought she would be furious and their new association dissolved. “I hope that didn’t’ shake you up,” Taylor said. Backstage she told Tammy Grimes, “Zev and I are doing a show together.” “That’s when I knew we were in business.”

The show, of course, would be The Little Foxes. The negotiations with Lillian Hellman were endless—“Anything you do with Lillian takes ten times longer than with anyone else,” he said—but after several fights The Little Foxes opened to rave reviews, an eighteen-month international run; the senator and his wife got divorced; Elizabeth Taylor turned to Bufman for comfort; and everybody involved, including Lillian Hellman, walked away a millionaire.

“Zev,” Taylor said later, “we really should be partners. I want to work. I have good ideas. Let’s co-produce.” Within weeks the partners in the Elizabeth Theatre Group were talking agenda—Inherit the Wind, The Corn is Green, Sweet Bird of Youth, and even loftier productions. Taylor said she wanted to take on the plays of “William Shakespeare.” Cicely Tyson was hired for The Corn is Green, Taylor herself for Sweet Bird, as she calls it. So was the director Milton Katselas, who hadn’t done anything on Broadway in twelve years.

Then they reconsidered. Why not do a comedy, something almost fun? And not just any comedy, but Private Lives, an almost actorproof confection that has served innumerable couples well over the past 53 years. In Elizabeth Taylor’s dressing room there is a terrific picture of Noel Coward walking with Mr. and Mrs. Richard Burton, circa 1965. “Noel used to tell us all the time that we totally fit in her play,” Taylor explained. She and Bufman took that as a mandate. Richard Burton, tanned and healthy and not drinking at all, flew out to Taylor’s house in Bel Air to discuss. Although Burton ahs never been known for his light-comedy skills, the deal was rich: $70,000 a week for both of them. Since Katselas was already hired, the producers decided to let him stay onboard. Therein many future problems would lie.

So, ensemble assembled, rehearsals began. Katselas told Taylor to hit the lines hard. “The audience wants to see Elizabeth Taylor,” he said. “Do you mean Richard and I should play Private Lives like the audience is looking into our bedroom?” she asked. “Yes,” Katselas said. Katselas is a heavy breather, his interpretation that of a voyeur. What he wanted didn’t work. By the time the comedy lurched into the Shubert, the cast was getting mutinous, and there were Taylor and Burton, at rehearsal, banging the lines. For example:

AMANDA: I feel rather scared of marriage really.

ELYOT: It is a frowsy business.

AMANDA: I believe it was just the fact of our being married, and clamped together publicly, that wrecked us before.

ELYOT: That, and not knowing how to manage each other.

Burton, as Elyot, held the final moment and stared deep into the Shubert, rows and rows of empty seats staring back. “Pause,” he said dryly, “for a fifteen-minute laugh.”

And then came opening night.

The word, as it always does, started drifting into Anthony’s Pier 4, where the party was being held, that this performance was staggering, the single greatest night so far, a sublime triumph for Taylor, and that the audience had responded, according to Charles Cinnamon, one of the three press agents attached to the show, but “hooting and stomping and giving Elizabeth and Richard at least five curtain calls.” Cinnamon was being aided by Chen Sam, an Egyption woman who is Taylor’s close friend and press rep. Trained as a pharmacologist, Chen Sam had been summoned to Botswana just before the second Taylor-Burton nuptials. Burton had gone on a long drunk, contracting malaria, and Chen Sam was flown in to save him. She did, and stayed on the payroll.

“Doesn’t anyone want to talk to Burton?” Cinnamon asked a knot of reporters. Nobody did, so Burton disappeared upstairs. Much later, the great squawk of walkie-talkies—“She’s coming, she’s coming”—began, the local anchorwoman began to crank up, the lights came on, and there was Elizabeth Taylor in a black chiffon caftan and thirties wig, absolutely terrified. She made the expected remarks about how much fun she was having, all the while clinging to Bufman, who looked as if he’d just gotten some dreadful news, and then she joined Burton who was drinking a cup of black coffee, his hand defensively atop his empty wineglass.

Anthony of Anthony’s Pier 4 had laid on seven courses, six wines, gold plates, and a band. Elizabeth danced, her cognac diamond earrings—“a very old gift from Richard Burton”—bobbling. Back at the table, she ate lobster, smiled into her butter dish, and talked for hour with Joan Kennedy and costars John Cullum and Kathryn Walker. Burton was very quiet, his new girl friend, Sally Hay, next to him. Zev Bufman looked grave.

“I don’t know,” Richard Burton said. “People thought I was mad when I did Hamlet, too.” It was 1:30 in the morning and Burton looked desperately bored, so tired his features began to run together. He was trying to analyze what he was doing in Private Lives. “I think there is some fun in it for me, especially when I start inventing my own lines. You remember that bit in the third act when I scream at Elizabeth, ‘Slattern!’ Well, I’ve enlarged that. So each night, I hurl a string of invectives at her—‘Slattern, yes, and vermin too, and fishwife, nightmare, horror’—and then Elizabeth will scream them all back at me. That gives me a great deal of amusement, although Noel must be spinning in his grave.

“Yes, I’m playing to the lines,” Burton said, “going for the laughs, the double entendres. There’s no doubt about it. You know, you can kill a laugh as quick as can be if you want to, by just coming in rapidly on the next line or moving fast.” As Burton spoke, he looked over as if magnetized, staring at Elizabeth Taylor, who was staring at herself in a compact mirror, applying a coral lipstick over and over to her bottom lip. It was hypnotic. Her face was as determined as a child’s, the cylinder moving across 22 times. “Elizabeth and I know each other so well by now,” Burton said. “We know how to play people.

Which meant, he said, “that we are beyond caring what people think of our motives.” Burton’s motive is the desire to work, to avoid the dissipation that hit Barrymore at the end, to simply stay onstage, rehearsing and overrehearsing until he drops. He badly needed this job, and Taylor will always help her former husband out of a jam. “It’s all purposeful, what we’re doing,” Burton said. “We’ve even discussed the strategy of what to say when the inevitable dull question crop up about our reunion becoming a reconciliation. The set piece is all organized. Elizabeth pretends she hasn’t heard, and I say ‘Next question’.”

Years ago, Elizabeth Taylor’s father taught her how to tune out any scene she did not want to see, to focus on the middle distance. That came in handy opening night when a reporter from USA Today rushed her the table, flinging a hand in Taylor’s face. Suddenly there was a great cry of “Chen-Chen-Chen! Security! Security!” The reporter was hustled away, and during the entire episode Taylor did not show one flicker of interest or emotion. Her face stayed exactly the same.

The fun was not to last. The next morning, Kevin Kelly’s review was headlined CLUMPING THROUGH. Taylor, Kelly said, was “perfectly terrible,” “a caricature of Coward’s heroine, inside a caricature of an actress, inside a caricature of Elizabeth Taylor. “A hefty housewife in a Community Theater farce,” he pronounced. Burton was treated almost as well. “We were expecting this,” Charles Cinnamon said, but Elizabeth “has been crying all morning.” Plans were being changed. Zev was supposed to take off for Florida, but now that would be delayed, and Chen put off a trip to L.A. Meetings were scheduled at the Shubert; Katselas, whose direction had been called “frenzied and awkward,” was on his way there now. “Everything is up in the air,” said Cinnamon. “We’re just going to rise above this,” Chen Sam said.

Backstage at the Shubert, three days later: “I’m on the verge of giving in my notice,” John Cullum said in his dressing room during the second act of a Sunday matinee. “Line readings! Can you imagine, this man is giving me line readings! And if he’s giving them to me, think of what he must be doing with Elizabeth! Do you know he told her that he wants to have dinner with her tonight to talk about the character and to work on her o’s and a’s?” “This man” was Katselas, clearly in way over his head. “This play is at a crossroads,” Cullum said. “Everybody is very hyper, and it could go either way.”

The fury had been building since the Boston opening. Everybody was defending Elizabeth Taylor. “She’s the kind of woman you want as a close friend.” The gloomy atmosphere at the Shubert, Kathryn Walker explained, could be traced to “an unconscious aggression toward Elizabeth and Richard’s celebrity” and to “a vicious transference process.” Milton Kastelas and his “voyeurism” were also to blame. Although Katselas seemed unbothered by the subcurrents—“I’m just tuning a Rolls-Royce,” he kept saying—Walker was very worried. “It is painful to stand with Elizabeth before we go on and see her look in the mirror and say, ‘Do I really look fat?’ She’s hurt, very hurt, and now they’re throwing her to the lions, the way she’s being directed. I don’t know what she can’t stand up to them.”

A flight of stairs and several dressing rooms away, Elizabeth Taylor, co-producer and star, was fending for herself quite nicely, having another meeting with Katselas after the day’s performance to determine, as Zev Bufman later said, whether there was any way we could avoid getting rid of him.” (There wasn’t. Lou Antonio, who recently directed Taylor and Carol Burnett in a TV movie, would be hired the followed week.) And a joke was making the rounds: Why can’t Private Lives find a new director? Because My One and Only has hired them all.

Moments after Katselas walked out, Taylor’s training to remain serene served her well. In a purple velvet caftan, lush as an overripe plum, she was lounging on a chaise, being absolutely kittenish about what was going on. All of her usual props were there—tropical fish in a large tank, lavender walls, and a bourbon, which she nursed a good hour. The years—or her love of bourbon—have robbed her face of its symmetry, and her eyes flickered with wariness, until she dropped the National Velvet accent and finally relaxed.

“You know what really annoyed me,” she said. “I was watching television in my dressing room and suddenly there was the local Boston anchorwoman talking to Kevin Kelly about Private Lives. He had just done his review, saying the most awful things, and here I am watching it—can you imagine?—and suddenly they start showing a scene from the second act. And I thought, ‘Isn’t that illegal? Don’t they have to have permission to do that? Can’t we sue?’ And at the end of it, this woman says, ‘Well, thanks a lot, Kevin. I’m going to save my $37.50 and not see Private Lives.’ Well, that just infuriated me! We’ve been sold out the entire run! I couldn’t even get tickets for my own children.”

Elizabeth Taylor’s eyes opening very wife. “I wonder if Kitty Kelley is related to Kevin Kelly. Think about it. They’re both K. Kellys. How interesting! Maybe Kitty Kelley is Kevin Kelly in drag. Or maybe the other way around.”

The Kellys don’t bother Elizabeth Taylor, verteran of emergency tracheotomies, pneumonia, Vatican protests, divorce lawyers, Debbie Reynolds’s and Sybil Burton’s spleen, an overpowering mother, a weight problem, and Louis B. Mayer. Nothing bothers Elizabeth Taylor very long. It’s been said over and over that throughout her life Taylor has found a great deal of perspective and conversational solace by detailing her brushes with death. It’s almost as if, by reviewing the detritus, she is able to convince herself that at least she continues to live.

Take the car crash that happened this winter in Israel. “There we were, in torrential rains, crossing a deep ditch, when suddenly a car came up directly behind us and smacked into the stretch limo the five of us were riding in. I went hurling through the air, nothing to stop me, landing with all my weight against the dashboard, my calf swelling about five inches in front of me—I saw it just pop right out! And a hematoma, an enormous hematoma, came out on my back, and there was blood spurting everywhere. Look at this leg of mine. It’s still bruised, it still is so painful. And I couldn’t think about anything but the terrible moaning. The first thing I heard when I found myself on the floor was all these excruciating moans and screams, and someone who was with us had a piece of metal miss his eye socket by a hair, and there we all were, stumbling and bloody—it was so awful, because we were in about five feet of water in the ditch. And we were on our way to Ariel Sharon’s farm, just stuck there. Fortunately an Arab driver happened along and gave us a ride. He didn’t know who we were or what we were doing there. But the irony of us dragging in to Sharon’s farm looking like these bloody refugees. And Sharon put ice packs on all of us and was terribly concerned, getting out blankets, calling the doctors, but what was amazing was that nobody was worried about themselves, everybody just kept saying to each other, ‘Are you all right?’ One man with broken ribs started massaging my hematoma, and I just had to say to him, ‘Stop it. You’re hurt yourself.’ That’s how much we cared.

“You name it, I’ve gone through it,” Elizabeth Taylor said. “I’ve had ups, downs, grays, blacks. I’ve had the most extraordinary life of anyone around.” So she is able to maintain some sense of humor about what is going on. “We’re still feeling our way. We’re rehearsing here, for heaven’s sake. That’s what out of town is for. Of course we have a lot of work to do. This is my first production. Zev and I are going to do a lot of things together—plays, films—and someday I intend to direct.” She laughed. “And believe me, I’ve had the tact not to point out to Richard that now he’s my employee.”

Her new activity is far preferable to that “terrible boredom I had in Virginia after John and I finished campaigning. I was home all the time, I just sort of laid back at that point in my life and didn’t do a thing. Then I began to watch the mindless boob tube. And I ate. I ate out of nerves, nerves, nerves, and got so fat. And then it became everybody’s business unless you’re working. This ‘How much does Elizabeth Taylor weight?’ thing really bores me and annoys me. I’m back near my fighting weight now anyway.”

And what about Joan Rivers’s constant attacks?

“Joan who?” she said. A beat. “Who’s that?” Another beat. “Is she that awful blonde?”

The Joan Rivers jokes she cannot be shielded from, but almost everything else that’s written about Elizabeth Taylor is screened by her entourage, as if she were a head of state. Elizabeth Taylor insists she has never read Kitty Kelley’s unauthorized biography. “It would infuriate me too much.” Her attempt to keep some truth about her life has led her to sue ABC. “The idea that they are going to do a show called The Lives and Loves of Elizabeth Taylor. There is no possible way they could know what was going on unless they were under my carpet or under my bed.”

Elizabeth Taylor tends to view any encounter with journalists as a collision, and avoids them as much as she can. This is a bit peculiar, given the extraordinary publicity gimmick of Taylor and Burton reuniting for Private Lives. Elizabeth Taylor does not dwell on those ironies, however. Now she is a businesswoman, and a pretty good one, her eye fixed on the bottom line. Only once in a while will something really irk her—for example, a recent column item saying she had given her baby granddaughter, Elizabeth Diane (“I think that’s her middle name—I can never remember”), daughter of Maria Burton Carson, a baby-size mink.

“Christ!” she shrieked. “That never happened! What kind of obscenity was that that was printed? How disgusting, a baby-size mink.” The eruption caused the omnipresent press rep to interrupt. “Don’t you remember that fur manufacturer who sent the mink to Maria and then put out the statement that it came from you? We told you about it a few months ago.”

“Crap,” Elizabeth Taylor said. “This is the kind of thing that goes on all the time. They just make this garbage up. It is so icky, so damn obscene. I would have never sent such a horrible thing to my granddaughter. I really am not that much of a vulgarian.”

Her four children have learned to cope. “They’re my best friends. I discuss everything with them. I’ve always wanted them to know exactly what was going on with me so they would never be confused by what was written.” The children are all fairly settled now, but have had their problems adjusting. “I remember once one of my sons came home with a terrible black eye, and I said, ‘Darling, what happened?’ and he said, ‘The kids at school were saying terrible things about you, and I wanted to defend you.’ And I looked at him very hard, and I said, ‘You do not have to defend me ever. You are not to do that. I just want you to know who I am and what I am, and then you’ll never feel you have to fight for my name again.’”

For the moment, the tears for the bad reviews are over, and Taylor, age 52, knows there is life way after Private Lives. She has houses to go back to, and jewels in the vault, and however homeless she might seem in the public imagination, he home, she says, now is in Bel Air. “That house is filled with memorabilia. All kinds of pictures, and so is my house in Gstaad, which has got even more things, even Liza’s first little ballet shoes.” But right now there is a great deal of business to think about. Private Lives is being filmed for cable; there is a tour planned. At the opening-night party in New York, everyone will be asked to wear white tie and tails—the star’s idea. Who knows, there may even be another marriage, and if so, Elizabeth Taylor, forever unsinkable, is already making plans.

“Okay, I have a question for you now,” Elizabeth Taylor said. “What color do you think my next wedding dress should be?” “Mauve,” I answered. “Mauve?” she squeaked. “Not mauve.” Okay, lavender then. “Never lavender,” she said. She watched her pet fish wending their way through the tank. “Red, baby. The next time I get married, I’ll be wearing all red. You can count on that.”