Horn of rhinoceros. Penis of tiger. Root of sea holly. Husk of the emerald-green blister beetle known as the Spanish fly. So colorful and exotic is the list of substances that have been claimed to heighten sexual appetite that it’s hard not to feel a twinge of disappointment on first beholding the latest entry—a small white plastic nasal inhaler containing an odorless, colorless synthetic chemical called PT-141. Plain as it is, however, there is one thing that distinguishes PT-141 from the 4,000 years’ worth of recorded medicinal aphrodisiacs that precede it: It actually works.

And it’s coming to a medicine cabinet near you. The drug will soon enter Phase 3 clinical trials, the final round of testing before it goes to the Food and Drug Administration for review, and with the FDA’s approval it could reach the market in as soon as three years. The full range of possible risks and side effects has yet to be determined, but already this much is known: Putting that inhaler up your nose and popping off a dose of PT-141 results, in most cases, in a stirring in the loins in as few as fifteen minutes. Women, according to one set of results, feel “genital warmth, tingling and throbbing,” not to mention “a strong desire to have sex.” Among men, who’ve been tested with the drug more extensively, the data set is, shall we say, richer:

“With PT-141, you feel good, not only sexually aroused,” reported anonymous patient 007, a participant in a Phase 2 trial, “you feel younger and more energetic.” Said another patient: “It helped the libido. So you have the urge and the desire… . You get this humming feeling; you’re ready to take your pants off and go.” And another: “Twice me and my wife had sex twice in one night. I came in [to work] and I just raved about it: ‘Jesus, guys … 58 years old and you don’t do that.’ ” Tales of pharmaceutically induced sexual prowess among 58-year-olds are common enough in the age of the Little Blue Pill, but they don’t typically involve quite so urgent a repertoire of humming, throbbing, tingling, and double-dipping. Or as patient 128 put it: “My wife knows. She can tell the difference between Viagra and PT-141.”

The precise mechanisms by which PT-141 does its job remain unclear, but the rough idea is this: Where Viagra acts on the circulatory system, helping blood flow into the penis, PT-141 goes straight to the brain itself. And there it goes to work, switching on the same neural circuitry that lights up when a person actually, you know, wants to.

“It’s not merely allowing a sexual response to take place more easily,” explains Michael A. Perelman, co-director of the Human Sexuality Program at New York Presbyterian Hospital and a sexual-medicine adviser on the PT-141 trials. Though he cautions against jumping to conclusions, he’s hopeful that the drug represents a breakthrough. “It may be having an effect, literally, on how we think and feel.”

Palatin Technologies, the New Jersey–based maker of PT-141, has hopes of its own. Once the company gets FDA approval for the drug, Palatin plans to market it to the same crowd Viagra targets: male erectile-dysfunction patients. Approval as a treatment for female sexual dysfunction may follow, perhaps bringing relief to postmenopausal and other women with truly physiological barriers to sexual happiness. In the wake of Pfizer’s failed attempts to prove Viagra works for women, and amid growing recognition that it doesn’t even do the trick for large numbers of men, these two markets alone could make PT-141 a pharmaceutical blockbuster.

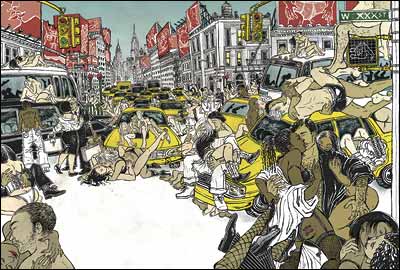

But let’s face facts: A drug that makes you not only able to but eager to isn’t going to remain the exclusive property of the severely impaired. As with Viagra, there will no doubt be extensive off-label use of PT-141. Fast-acting and long-lasting, packaged in an easily concealed, single-use nasal inhaler, unaffected by food or alcohol consumption, PT-141 seems bound to take its place alongside MDMA, cocaine, poppers, and booze itself in the pantheon of club drugs. If the chemical is all it’s cracked up to be, the perennial pharmacological dilemma of the pickup scene—namely, how to maximize the fun when the drinks required to set the mood are always more than enough to dull the senses—would appear to have found its solution.

You’ve been there yourself, after all: a third or fourth date, a late night of rich food, hard liquor, mildly exhausting erotic tension. Can you admit to yourself now, however hungrily you may have anticipated the evening’s scheduled consummation, that there was a part of you, when the moment arrived, that really would have rather been at home watching CSI?

And let’s say things worked out between the two of you, so well, in fact, that you are together to this day, each still the light of the other’s life so many years after the light first flickered on. Can you honestly say, however excellent the sex remains, that there haven’t been moments, weeks, whole seasons, when the dogged stresses of daily life seemed to have wrung the last drop out of your sex drive? Or that these moments haven’t sometimes nudged you to doubt yourself and your relationship? And that if given the opportunity to propel a chemical spray up your nose that would revive the enthusiasm and snuff out those doubts like the needless, counterproductive anxieties you ultimately convinced yourself they are, you wouldn’t lay down your credit card first and ask questions later?

“He notices it’s there, and he grooms it to detumescence. And then it happens again.”

The potential market for PT-141, in short, is all of us. And the potential transformation of the modern American sex life is no less sweeping. Consider the precedent: Just more than four decades ago, it was another drug’s arrival in the marketplace that triggered what would eventually be called the sexual revolution. Before the advent of the birth-control pill, sex and procreation had been eternally, inseparably linked. After it, the link was pretty much optional. Momentous things ensued: women’s liberation, gay rights, the abortion controversy, all of them arguably the Pill’s indirect consequences, all of them reverberating to this day. And if all that can follow from a drug that simply made pregnancy less a matter of fate than of choice—what then to expect from a drug that does the same thing to passion itself?

Only when and if PT-141 reaches the market will we be in a position to even start answering that question. In the meantime, though, it can’t hurt to practice. And for now, there probably isn’t a better way to hone the question than to turn it on the individuals that have given more than any others—in blood, sweat, and other bodily fluids, at least—to make the question possible: the rats of the Palatin Technologies research labs.

“In a rat, there’s a mating ritual,” says Palatin CEO Carl Spana. “The female rat will approach the male head-to-head. She will wiggle her ears, she will wiggle her whiskers, she will nibble at him, and finally she’ll turn and run away.” If the male chooses not to pursue her, she may return and, as one leading rat sexologist puts it, “kick him in the face.” This tends to do the trick. The male gives chase, catches the female, and climbs on top of her, at which point only two key preparations remain to be completed. First, so that the female’s low-slung genitalia can be reached from above, her hindquarters will bend upward in a reflexive arching of the back called lordosis. Second, so that the male may take advantage of this invitation, his penis will stiffen and emerge from its hiding place under the abdominal fur. “And then,” Spana concludes, “they copulate.”

Spana’s familiarity with the sex life of rats is, of course, no accident: Their role in the development of PT-141 was pivotal. Years before the drug’s first human test patient felt that telltale humming in his pants, it was the lab rats of Palatin that established the drug’s potential for promoting what’s known in the trade as erectogenesis. The experiment, repeated hundreds of times, was a straightforward one. “You dose and you watch and you count,” Spana explains. Every time the penis of a subject rat emerged, stiff and ready, observers marked down the event in a notebook. The subjects, all “naïve” adults whose last contact with a female was on the day their mothers weaned them, seemed to have had, if anything, slightly less curiosity about their spontaneously generated boners than the researchers. The typical reaction: “He notices it’s there, and he grooms it to detumescence,” says Annette Shadiack, Palatin’s executive director of pre-clinical development. “And then it happens again.”

The high wood count was good news for Palatin’s management, who were banking on PT-141 to prove itself an effective treatment for erectile dysfunction. Two years earlier, and just three years past its start-up, the company had bought the rights to develop a substance called Melanotan II. Originally isolated by University of Arizona researchers looking for a way to give Caucasian desert-dwellers a healthy, sunblocking tan without exposing them to dangerous ultraviolet rays, Melanotan II achieved that modern miracle and more: It also appeared to facilitate weight loss, increase sexual appetite, and—why not?—act as an anti-inflammatory too. Quickly dubbed “the Barbie drug,” Melanotan II seemed too good to be true.

In fact, it was too good to be good. A drug with so many effects, Palatin decided, was not an effectively marketable one. So Palatin’s researchers set out to isolate the individual effects in the laboratory, experimenting with variations on Melanotan II’s molecular theme. As it happens, the compound that became PT-141 was one of the first variations examined, and the rat boners spoke as if with one voice, saying, “Here is your candidate.”

The market analysis was equally encouraging. As a late entrant in the market for erectile-dysfunction treatments, PT-141 stood a decent chance of mopping up the floor. By this stage in Viagra’s life cycle, for instance, it was clear that the drug solves nothing for perhaps 50 percent of impotent patients, either because their general health is too poor to risk Viagra’s side effects or because it simply doesn’t work for them. But existing Viagra users weren’t exactly out of play either: PT-141 had a potential edge not just in ease of use but in quality of, well, results. (“On the five-point scale,” said patient 041, “I would rate the erection I had as a six.”) And there was a final and especially intriguing possibility: Since PT-141 affects arousal through a different, more brain-centric mechanism than Viagra, might it not boldly go where Viagra had failed to penetrate—into the female sexual-dysfunction market?

It was in pursuit of the women’s market that Shadiack approached Concordia University behavioral-neurobiology researcher Jim Pfaus, whose work with sexual response in female rats had caught her attention. Where the bulk of research into female-rat sexual behavior has focused on lordosis—that reflexive arching of the lower back that signifies the female is as ready as she’ll ever be—Pfaus has taken what might be called a more feminist approach. Instead of lordosis’s almost climactic spasm, he prefers to look at foreplay: the wiggling of ears, kicking of faces, and other acts of solicitation with which female rats reveal their desire to the partner of their choice.

Pfaus discovered that PT-141 significantly increases the incidence of these behaviors. He even detected an increase in the rarer phenomenon in which a female rat will throw coyness to the winds and, in a performance worthy of Kim Cattrall, mount the chosen male herself.

“You have the urge and the desire. You get this humming feeling; you’re ready to take your pants off and go.”

And thus the case was cinched. Pfaus’s results were powerful evidence not only of PT-141’s potential as a treatment for women but of its ability to do more than just move blood around. Granted, a male rat’s hard-on has a nice, solid objectivity to it, but on its own it doesn’t say much about the rat’s state of mind. A female rat’s coquetry, on the other hand, says all we need to know about her intentions and desires—and says it, moreover, with an invaluable honesty. Rats aren’t people, to be sure, and as test subjects they suffer from an often frustrating inability to tell us, in words, how they experience what they’re subjected to. But that has an upside too, Pfaus explains. “The bad thing about animals is they don’t talk. The good thing is they don’t lie.” They don’t get all weird about sex the way humans do when asked to talk frankly about it. They don’t try to guess what their examiners hope to hear, or shape their answers to their parents’ expectations, or their mate’s, or their own. They don’t tweak, warp, and violate the truth about sex in all the many ways, great and small, knowing and unknowing, that humans do.

So the testimony of rats—notwithstanding the 900 articulate, full-grown human subjects who have since reported enhanced arousal and desire from taking PT-141—remains the most objective evaluation the drug has yet received, or ever will. I see a lot of couples in my practice—lawyer couples, banker couples—who don’t know how to relax,” says Leonore Tiefer, a professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine. “That’s fine—it’s a big asset to them in their corporate lifestyle, where they can work 80 hours a week—but then I have to shut off two BlackBerrys in my office in order to keep the noise down. They’re trained to multitask. Well, it doesn’t seem that that is really doable when it comes to sex. And they’re angry about that: It should be doable. And they need it to be doable because they only have five minutes.”

The five-minute meaningful sexual encounter: If ever there was a holy grail for the age of the tight-wired global economy—with its time-strapped labor force and its glut of bright, shiny distractions—that is it. And if ever there was a reason to be leery of the pharmaceutical industry’s designs on the market for sexual healing, say critics like Tiefer, it’s the attractiveness of that simpleminded ideal.

Tiefer is one of the leading figures in a movement of academic researchers, sex therapists, and women’s-health activists contesting the increasing medicalization of women’s sexual problems, and when Procter & Gamble sought FDA approval last December for its “female sexual-desire disorder” treatment—a testosterone patch called Intrinsa—her testimony helped sway the agency to deny the request. Unlike the counting of erections, assessing subjective phenomena such as desire and satisfaction is, she testified, “subtle, complex—and arbitrary.” P&G’s findings were thus too inconclusive to hold their own against the established risks of long-term testosterone use. “Intrinsa is not a glass of Chardonnay,” she remarked, “and yet we have already seen that it may well be promoted with a giggle and a wink as ‘the female Viagra.’ ”

Tiefer is just as dubious about PT-141, which, as she sees it, is merely the latest expression of a “big wish” that “we could just bypass everything we want to bypass” on our way to sexual happiness, skipping the complicated, often lifelong work of sorting out all the emotional, physical, and autobiographical triggers that turn us off and on. Her prognosis for the discovery of a drug that will make that work unnecessary? “Sorry, it’s never going to happen.” And in the meantime, she suggests, there will always be some “promising” new treatment that captures our minds and our money long enough to half-convince us the problem’s been solved. “And then it will be forgotten, and then a few years later something new will come along,” says Tiefer.

Perhaps, perhaps not. Yet even assuming that PT-141 ultimately performs every bit as well in broad use as it has in trials, even granting that it can improve sex lives as effectively as a lifetime of erotic exploration, the deeper challenge posed by the prospect of a sexual techno-fix remains: Is this really the kind of fix we want? To have desire available at any time, from the nozzle of an inhaler?

Good things would come of it, to be sure. Marriages would be saved, fun would be had. But sexual Utopia? PT-141 seems just as likely to usher in the age of McNookie: quick, easy couplings low on emotional nutrition. Sex lives tailored to the demands of a jealous office or an impatient spouse. A dark age of erotic self-ignorance tarted up in the bright-colored packaging of a Happy Meal.

Think it won’t happen? Think again, then, about those moments when your sex drive stalled and your mind filled with anxieties that you ultimately managed to talk yourself out of. Now imagine that you failed, in the end, to talk away the anxieties; imagine you instead found yourself obliged to listen to them, and that they told you things about yourself, your life, that you hadn’t wanted to hear but finally had to acknowledge were true. Imagine that as a result of all this listening, you understood at last that you had to, for instance, leave your husband, your wife, the man or woman you’d first slept with on that third or fourth date, the one full of rich food, hard liquor, etc.; and that now that you thought about it, the voice inside you that night that had wanted you home watching television had sounded a lot like the one now telling you to leave your marriage, and that, all things considered, you probably should have paid more attention to it then.

Now imagine the whole story all over again, except that at the very moment these anxious voices start to pipe up, you find yourself with an inhaler of PT-141 and a decision to make: You can either take your sexual dissatisfaction seriously and learn from it, or you can take a hit of PT-141 and write off your anxieties as nothing more than fallout from the mild case of sexual-desire disorder the drug will soon have under control. Which do you choose? Self-knowledge or self-content? The awful truth or the convenient fiction?

Take your time.

Deep in the postindustrial hinterlands of New Jersey, about a mile and a half from Exit 8A off the turnpike, 100 snow-white Sprague-Dawley rats await the coming of darkness. Darkness comes each day at exactly 6 p.m., when an automated switch turns off the fluorescents and sets off a rustling din, like the sound of a sudden downpour, as all at once the rats rouse themselves and start to feed. They live in see-through high-rises: small Plexiglas cages stacked eight by eight in portable racks, one rat per unit, each unit connected to the outside world by its own HEPA-filtered ventilation system. Other perks of life as a lab animal at Palatin Technologies’ Cranbury, New Jersey, headquarters include immaculate bedding, healthy supplies of food and water, bone-shaped plastic chew toys, and, screwed into the top of each animal’s skull, a small, white, almost stylish ceramic orb, the injection port through which the rats’ brains are regularly dosed with a close chemical cousin of PT-141.

The drug they’re testing now is an obesity drug—designed to block the appetite for food in much the same way PT-141 stimulates the appetite for sex—and its distinctly human goal of weight loss serves only to heighten the pervading Stuart Little effect here in the lab. Crowded in their little Plexiglas apartment buildings, sporting their natty little orbular skullcaps, undergoing surgery from time to time with little rat-nose-shaped anesthetic-gas masks strapped to their little faces—if you didn’t know better, you might start to think of these sophisticated rodent urbanites as simply little people with fur and whiskers. Which, in a way, is just what Tiefer accuses Palatin of doing: confusing the lush subjectiveness of human sexuality with the black-box behaviorism of lab animals.

The funny thing is, it appears there’s a certain humanlike subjectiveness to the sex life of lab animals as well. When Jim Pfaus tested PT-141 on his female rats, he based his experimental design partly on the work of Raul Paredes, a fellow rat sexologist testing the effects of something more elusive: personal autonomy. That’s a tricky thing to measure, but it can be done. Paredes did it like this: First, he looked at rat couples living in standard, box-shaped cages and recorded the details of their sexual behavior. Then, he altered the cages in only one particular: He divided them into two chambers with a clear wall broken only by one opening, too small for the males to get through but just right for the females. Architecturally it was a minor change, but what it did for the females was huge. It let them get away from the males whenever they chose to, and thereby made it entirely their choice whether to have sex. Paredes then observed the rats’ behavior in this altered setting. Here’s what he found: The effects of giving a female rat greater personal control over her sex life are essentially the same as those of giving her PT-141. Autonomy, in other words, is as real an aphrodisiac as any substance known to science.

Is this really the kind of fix we want? To have desire available at any time, from the nozzle of an inhaler?

This doesn’t surprise Leonore Tiefer, who sees evidence for it every working day, in sex lives that suffer in direct proportion to her clients’ ignorance about desire in general and their own in particular. For Tiefer, striving to understand yourself is the sexiest sort of autonomy there is, and nothing betrays that autonomy like handing over the job to someone else, whether it’s your lover, your doctor, or, worst of all, Big Pharma.

Jim Pfaus, not surprisingly, sees things a little differently. As it happens, Pfaus and Tiefer are friendly acquaintances, and he’s sympathetic with her critiques of the industry. “She’s on a roll, and I think she has some valid points,” says Pfaus. But all the same: “What do we tell postmenopausal women who have lost their desire, despite being in a loving and caring relationship? ‘Sorry, there’s nothing we can do,’ or worse, ‘Sorry, but you shouldn’t be having sex anyway?’ ”

The argument is a strong one. But so is Tiefer’s. Each defends a vital sort of autonomy—the power of self-knowledge on the one hand; on the other, the freedom to grasp whatever tools of self-betterment are available to us. And if, after all the trials are done and the prescriptions are filled, PT-141 diminishes the former as much as it expands the latter, who’s to say which matters more? Add up all the pluses and minuses, and in the end the sum may be zero: a wash. In short, no net change one way or the other in the world’s total supply of sexual happiness.

But then, no one’s asking PT-141 to change the world. It’s enough to hope that someday, when you need it most, it just might get you through the night.