It’s 7:30 p.m. in Soho, that magic hour when the scent of first-course dishes wafts heavenward from the tables at Savoy, the anxiety of last-minute meal planners courses through the aisles of Dean & DeLuca, and a grown man’s fancy turns to thoughts of food. My own thoughts, at the moment, are of practically nothing else. Half-sprinting through the Prince Street crowds, I am late for a dinner party I’ve been planning for weeks, and I’m starving.

I’ve been starving for the past two months, actually, and that’s precisely what the party is about: My dinner guests—five successful urban professionals who for years have subsisted on a caloric intake the average sub-Saharan African would find austere—have been at it much, much longer, and I’ve invited them here to show me how it’s done. They are master practitioners of Calorie Restriction, a diet whose central, radical premise is that the less you eat, the longer you’ll live. Having taken this diet for a nine-week test drive, I’m hoping now for an up-close glimpse of what it means to go all the way. I want to find out what it looks, feels, and tastes like to commit to the ultimate in dietary trade-offs: a lifetime lived as close to the brink of starvation as your body can stand, in exchange for the promise of a life span longer than any human has ever known.

Seat belts, vaccines, clean tap water, and other modern miracles have dramatically boosted average life expectancies, to be sure—reducing annually the percentage of people who die before reaching the maximum life span—but CR alone demonstrably raises the maximum itself. In lab studies going back to the thirties, mice on severely limited diets have consistently lived as much as 50 percent longer than the oldest of their well-fed peers—the rodent equivalent of a human life stretched past the age of 160. And it isn’t just a mouse thing: Yeast cells, spiders, vinegar worms, rhesus monkeys—by now a veritable menagerie of species has been shown to benefit from CR’s life-extending effects.

Despite the mounting evidence, however, the link between CR and longevity remained for many years a medical curiosity, its implications for human health intriguing, certainly, but unexplored. Partly this was because nobody, to this day, has figured out exactly how the CR effect works. Some have suggested that the threat of starvation triggers certain self-preservative responses in animal physiologies; others have pursued a sort of “fuel efficiency” hypothesis, proposing that lightening the body’s load of food-energy processing reduces wear and tear on cellular machinery. But no one theory has ever settled the question firmly enough to prove that humans would benefit from CR as much as other animals have. That has left direct experimentation as the next best route to an answer, and for obvious reasons, finding human subjects willing to live on concentration-camp diets has historically been a tricky proposition.

In 1991, however, the proposition was simplified somewhat when a team of eight bioscientists sealed themselves up for a two-year stint inside a giant, airtight terrarium in the Arizona desert—and promptly discovered that the hypothetically self-sustaining ecosystem they’d settled into could barely grow enough food to keep them alive. This revelation might have doomed the experiment (known as Biosphere 2) but for the fact that the team’s physician, UCLA pathologist Roy Walford, had been studying the Calorie Restriction phenomenon for decades and convinced his fellow econauts that—as long as they all ate carefully enough to get their daily share of essential nutrients—a year or two of near starvation wouldn’t hurt. When at last the Biosphere 2 crew emerged from their bubble, tests proved them healthier in nearly every nutritionally relevant respect than when they’d gone in, and the case for Calorie Restriction in humans was no longer purely circumstantial. Fifteen years later, Walford’s CR primer, Beyond the 120-Year Diet: How to Double Your Vital Years, is in its fifth printing, and an estimated 1,400 people have taken up the diet as a full-time, lifelong practice.

It isn’t hard to see the diet’s appeal to a certain very familiar New York type: You’re skinnier than any social X-ray, you’re practicing a regimen as extreme and as grueling as any yogi’s, and you’ve got some impressive medical science on your side. For someone attracted to control, accomplishment, and power, this is the life. And I’m living it.

The hardest part, I find, is the math: not just the labor of tracking everything I put in my body but the way in which calorie counting makes the no-free-lunch adage so viscerally clear. Bacon cheeseburgers, chocolate, a martini—all are pleasures now completely ruined by the knowledge that the massive caloric debts that they create must be paid for with days or even weeks of caloric cutbacks. Other abnegations—the dinner invitations regretfully declined, the awkward orders of soda water on the rocks at “drinks” with friends and colleagues, the freakishly ascetic feeling of sitting gaunt and empty-plated before a calorie-packed family dinner—are met with the compensatory feeling one gets when walking a righteous, if lonely, path.

So I’m genuinely thrilled to meet five newfound fellow travelers when at last I burst into the kitchen of a white-walled caterer’s loft I’ve borrowed for the occasion of my dinner party. Each of my guests is prominent among the CR movement’s hard core: Paul McGlothin, a 58-year-old Manhattan-based ad exec and volunteer director of research for the nonprofit Calorie Restriction Society; Paul’s wife, Meredith Averill, 60; April Smith, a 32-year-old Philadelphia union organizer and author of April’s CR Diary, a highly readable and (within the CR community, at least) widely read online journal of her calorie-restricted life; her Canadian boyfriend, Michael Rae, a full-time research assistant to life-extension guru Aubrey de Grey and a prolific, authoritative presence on the CRS mailing list; and Donald Dowden, a midtown lawyer and CR poster boy. There’s no mistaking the peculiarly lean little crowd gathered here, and the recognition is mutual. Paul, blue-blazered, gray-haired, with the face and gaze of a preppy Don Knotts and the approximate body-mass index of a Noguchi floor lamp (five foot eleven, 137 pounds), gives me a once-over and grins. “You look,” he says, “like one of us.”

I’ll take that as a compliment, I think. The 1,800 daily calories I’ve been consuming fall well short of the minimum 2,500 recommended for adult males, and two months on this caloric budget has shrunk my 43-year-old, five-eleven frame from an almost officially overweight 178 pounds to a high-school-era 157. Friends and loved ones, I’ve noticed, have started sounding more concerned than impressed when they see how much weight I’ve lost, but here within the charmed circle of tonight’s dinner party, I don’t feel so much scrawny as trim—dashing, even. Standing around the kitchen’s broad butcher-block prep table with these five world-class calorie restricters, I recognize our thinness as sophisticated and sane, the height of a slender, Nick and Nora Charles sort of elegance.

Though I’m our official host, it’s the compact, wisecracking April Smith who presides. April has volunteered to plan and cook tonight’s CR-correct menu, and her sous-chef for the evening, Michael, stands beside her at the ready: a boyish-looking 35-year-old with brush-cut red hair, translucently pale skin, and—at six feet tall and 115 pounds—an eerily spare physique.

Consider those dimensions for a moment. Divide Michael’s weight by the square of his height and you get a body-mass index of 15.6. Compare that with the minimum BMI of 18 recently decreed by the organizers of the Madrid Fashion Week—who cited the World Health Organization’s definition of 18.5 as the lower limit of healthy weight and offered medical assistance to any models who couldn’t meet it—and you might wonder how Michael can stand up in the morning, let alone jog twenty miles a week. But jog he does, and if the results of both his latest physical and the latest CR research are anything to go by, Michael is probably one of the healthiest 35-year-olds on the planet.

“Michael, could you hand Don the arugula?” April calls over her shoulder, looking up from the laptop that’s always near to hand as she cooks, loaded with an interactive diet-planning program that helps not only count calories but track the twenty other nutrients without which CR would just be a glorified form of anorexia. “Don, I need you to put 24 grams on each plate, please.” And so Don Dowden, attorney at law, commences weighing arugula on an electronic postage scale, carefully adding a leaf here, removing one there, like a drug dealer parsing out dime bags. Tall, dark-haired, craggy, Don gets by on a ration of about 2,000 calories a day and swears by its rejuvenating effects. “I used to wear glasses, but I don’t wear glasses anymore,” he says. “I don’t have 20/20 vision, but I can drive, and I can read the paper, and I’m 74.”

“You’re 74 years old?” I blurt, not so much astonished as simply confused. It’s not that I can’t see Don’s age in his face and skin, now that I know to look for it. But there’s something in the way his body moves, the way he holds it—an ease and an assuredness—that doesn’t quite square with the fact that he was born before FDR took office.

“He gets that a lot,” says Michael, a trace of glee in his otherwise quiet, clipped, north-of-the-border tone. April has him chopping asparagus now, while she continues crunching numbers. Tonight’s calculations are based on Michael’s caloric requirements, and those requirements are as strict as they come. Unlike April’s daily average of about 1,300 calories, which really is an average (she likes to go out drinking and dining with friends on weekends, and doesn’t mind enduring a few 1,000-calorie weekdays to save up for the splurge), Michael’s regimen of 1,913 calories a day is exactly that: 1,913 calories every single day, 30 percent of them derived from fat, 30 percent from protein, and 40 percent from carbohydrates. Cooking for him is the same elaborate exercise in dietary Sudoku it is for all CR die-hards, only more so.

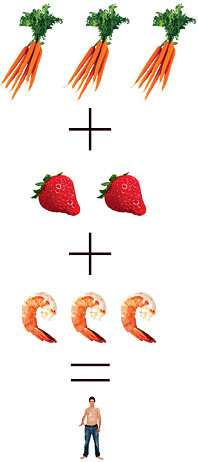

“Michael’s dinner is always 639 calories,” April explains, eyes on the screen while her fingers dance across the keyboard, tweaking portions. She makes the job look easier than it can possibly be, like one of those kids who can solve a Rubik’s Cube in under a minute. “I’m so used to doing this now. If I need more protein, I add more protein. If I need a little bit more carb, I add more strawberry. Ohhh, and I forgot the ricotta for the dessert … see? Now I have to mess with it. So 45 calories of nonfat ricotta, so I have to take out some protein, so I need to take out another scallop from the salad. Take out some strawberries from the dessert … What’s half of 90? What’s 90 plus 45? 135. Now we’re a little low, so add a bit more fat. See? Isn’t that beautiful?”

April turns the laptop to show me her numbers and yes, God help me, I do see the beauty. Though the full apparatus of scales and software isn’t a mandatory feature of the calorie-restricted lifestyle (Don, for instance, is unrepentantly low-tech, getting his calorie counts from food labels rather than databases), I’ve been using both from the outset, and I know only too well the virtuosity it takes to throw together a perfectly balanced 639-calorie meal plan on the fly. Me, I’m just happy I’ve mastered enough of the basics to know where I’m hitting my numbers (133 percent of my recommended daily allowance for fiber, 108 percent for riboflavin) and where I’m not (zinc at a distressing 64 percent).

April, too, seems pretty happy with my accounting skills. “We’re so proud of you,” she says as I rattle off my scores, and I get the impression she means it. She is famous in CR circles for her impatience with those who think they can get the diet right without a clinical attention to data, and it’s as if my own fastidiousness about the numbers were a personal victory for her. She’s also pleased to hear that a hunger-management tip she wrote up in the CR Society newsletter a few months back—start the day with a big protein load if you want to head off afternoon carb cravings—has become part of my daily routine.

“Finally, someone who follows my advice,” she says, tossing a wry look at Michael, who tosses it back.

“Oh, definitely, every morning I’ve been having a big, thick, soy-based protein smoothie for breakfast,” I continue, basking in the warmth of my CR elders’ approval and failing, for a moment or two, to notice that the smiles have suddenly dropped from their faces.

“You haven’t read the articles about soy and dementia?” Michael asks.

“Soy and dementia? Well … no,” I confess, feeling like I’ve just failed a pop quiz. “I did read about that one study linking soy and male aggression, but … ”

Yes, and now that we’re on the subject of health risks, there’s something else April needs to discuss with me.

“You’re losing weight too fast,” she says, with the crisp authority of a doctor handing me some bad but easily remedied news. “You’ve lost twenty pounds in two months, and you probably shouldn’t lose more than five pounds a month. You need to start eating more.”

This appears to be a cue for the evening’s two alpha geeks—Paul and Michael—to launch into dueling mini-lectures on the dire biophysics of rapid weight loss. “When you do CR, you’re not just losing fat,” Michael explains. “You’re losing muscle; you’re losing bone.” Shed weight too fast, and you can even shrink the most important muscle you have, your heart, running the same risk of cardiac arrest that makes anorexia such a dangerous obsession. “Yeah, sure, all that,” Paul jumps in, “but the real thing is your immune system.” Paul seems rather fonder of arcane medical jargon than Michael, and I’m not sure I follow why it’s my white blood cells I really need to worry about, but I’m not inclined to doubt him on it. This is a man, after all, who haunts his local medical lab the way some men haunt casinos, hewing to a schedule of testing so meticulous that one out-of-state lab has come to rely on Paul’s results to calibrate its own blood-testing equipment.

“Did you get your blood tested at the beginning of this?” Paul asks, and I confess I didn’t: Yet another misstep exposed. It’s humbling getting schooled like this. Yet even in the midst of it, I can’t help feeling a twinge of pride: I’ve just been told by three of the most hard-core calorie restricters on the planet that my own CR is too extreme. That’s got to make me sort of hard-core too, right?

A sixth guest arrives: my friend Adam, whom I’ve invited along for a variety of reasons, including both his outside perspective and his promise to bring a bottle of wine. It’s a Pinot Noir, per April’s request—the grape of choice for the calorie-restricted set, rich in anti-aging resveratrol—and she has Adam fill our glasses with exactly 74 calories’ worth of it. Well, some of our glasses. Paul and Meredith practice a one-meal-a-day variety of CR, and it so happens they already ate. “Cheers, anyway,” says Paul, quite cheerfully, as he and his wife raise their glasses of water with us.

We move to the table, which April has set with the salad course: the aforementioned 24 grams of arugula per plate, dressed with lemon juice and cushioning a couple of scallops sautéed in garlic, white wine, and cilantro. We begin to eat, and I experience a minor culinary epiphany: Mildly sickened by the taste of scallops for most of my adulthood and afflicted, for as long as I can remember, by an aversion to cilantro that borders on the emetic, I find myself now tucking into April Smith’s cilantro-infused scallops-and-arugula salad as if it were the best salad I have ever tasted. And I’ll be goddamned if it isn’t.

It isn’t hard to see the diet’s appeal: You’re skinnier than any social X-ray, you’re practicing a regimen as extreme and as grueling as any yogi’s, and you’ve got some impressive medical science on your side.

“Your sense of taste really does become enhanced when you’re hungry for your food,” Michael observes. “You appreciate it more.” This, on the one hand, is a point so staggeringly obvious as to defy comment, and on the other, it’s a truth whose full depths can probably only be known to people who’ve gone hungry as long and as purposefully as this party has. There are nods of agreement all around the table. “I love to cook, and it is so satisfying to cook for those who enjoy their food,” adds April. “I really hate cooking for people who don’t do CR now.”

Now more than ever, I can see her point. Perhaps you’ve noticed yourself how grudgingly appreciative your non-calorie-restricted dinner guests can be—the way they refuse, for instance, to consider themselves properly served unless you’ve given them actual food that they get to actually eat? Contrast this with the far more enthusiastic attitude of Paul McGlothin, who sits to my right before an empty place setting, nursing his water and praising the food on the table almost as if it were on its way to his own mouth instead of everybody else’s. “Looks great! Smells great!” he gushes. “Just watching you guys eat and smelling it, I know that tomorrow, when I break my fast, it’ll just be great. It’ll be terrific!”

Had I noticed the manic gleam in Paul’s eye before this? Maybe not, but there is no mistaking it now, and as I contemplate his peculiar fervor for the food he isn’t eating, I am brought face to face at last with a question that’s been taking shape within me from the moment I met him: Dude, are you high?

I don’t put the question to him in quite those terms, but his answer, basically, is yes: He is high, and chemically so. “When you fast for seventeen hours at a low glucose rate, brain-derived neurotrophic factor is released, which is a chemical which creates optimism,” says Paul. “This brain-derived neurotrophic factor is actually a natural part of the chemical thing that happens to me every day … I feel pretty exhilarated right now.”

I believe him, but only because I’ve felt something like it myself.

It’s no secret. From mystics to anorexics, people who go for long periods without eating often report feeling more awake and energetic, even euphoric. It’s nice for a while, but even the calorie-restricted can get too much of it. When April started CR, she often went long stretches between meals and eventually decided something was a little off. “It makes you feel like you’re on drugs; I got too euphoric,” she says. “You know, thinking you’re in love when you’re not.” She switched to a more consistent, balanced eating schedule, came back down to Earth, and that, she says with a shrug, was that:

“It’s like, ‘Eat something! You’re not in love.’ ”

April brings the main course: a medley of asparagus tips, shiitake mushrooms, and the featured ingredient, an unlikely hybrid of life-giving wholesomeness and bio-industrial hubris known as Quorn.

Quorn, at last! For as long as I’ve been following the blogs and mailing lists of the greater Calorie Restriction community, I’ve been reading about this patented wonder morsel, perhaps the ultimate in CR-friendly foods. Grown in fermentation tanks from a cultured strain of the soil mold Fusarium venenatum, Quorn in its virgin state is almost pure protein and very low in calories. Processing adds various essential nutrients, including a generous helping of zinc, which is concentrated in almost no other food but oysters and which the calorie-restricted can never get enough of. The end product tastes and chews remarkably like an unbreaded Chicken McNugget and can substitute for meat with all the versatility of soy (Quorn dogs, Quorn cutlets, and Quorn roasts are just a few of the faux-flesh varieties on offer) yet with fewer saturated fats and none of the alleged dementia-and/or-male-aggression-causing properties.

“Delicious,” says Don, digging in.

“Delicious,” I agree, lifting a forkful to my mouth.

“Not bad,” concedes Adam, surprising us all.

Bellies beginning to fill, a wineglass or two refreshed, our attention turns now to a topic that has hovered at the edges of conversation all evening: sex and the CR couple. There’s no escaping it. Of all the physiological inconveniences known to face the long-term calorie restricter—chills that sometimes accompany reduced metabolism rates, stamina deficits that can cut short the capacity for protracted physical labor—none strikes dismay into the heart of the initiate quite like CR’s potential, often mentioned but little understood, to squelch the libido. I’m happy to report the diet has so far spared me that particular side effect, but I’m eager to hear from the present company what CR has done to their sex lives. And they are just as eager, it seems, to tell me.

“Michael and I have more, better sex than all of you combined,” April announces, opening the discussion. “Ha! Speak for yourself,” Meredith retorts, seconded by her husband’s standard comment on the sex-and-CR problem: “Not a problem in our household.”

Or in most calorie-restricted households either, they insist. Not everybody on CR complains of lessened sexual desire, for one thing, and none of those who do, it seems, are women. (“If anything, women have the opposite problem,” April observes.) Nor are the reported side effects nearly as bad as what the “normal” aging process does to midlife sexual function. “Remember,” says Paul, “Meredith and I are in our late fifties, and we do know the sexual habits of people around our age.” The calorie-restricted middle-aged couple very likely doesn’t have the clogged arteries, sluggish endocrine systems, and other buzz-killing problems that conspire to extinguish many an older couple’s sex life.

All the same, says April, after all the record-straightening is done, “it’s not entirely a myth”: CR can in fact do strange things to the male libido. And, by way of illustrating the point, she begins to tell us what is probably the CR community’s best-known love story—her own.

“I met Michael at CR3 [the third annual Calorie Restriction Conference], in Charleston, but I stalked him for eight months before that,” says April. A recent convert to Calorie Restriction, she was an avid reader of the CR Society mailing list and, in particular, of Michael’s frequent postings to it. “I loved his writing. I thought he was absolutely brilliant and funny and developed a huge crush on him, and I just assumed he was probably 57 and married with five children, seventeen grandchildren, a lover, and a mistress. But eventually I saw a CBC interview with him about CR and saw that he was close to my age, and really cute, and just my type. And the interview showed him in his house making his little stir-fry all by himself and sitting down at the table all by himself with these hideous lime-green place mats. Just hideous. And that told me, one, he was straight, because no gay man would have these place mats in his home, and two, he was single, because no woman would have these place mats in her home. So I thought I’d capture him and take him to my country. And we’re closing on our house on Friday.”

There is a momentary silence, in the midst of which Paul bursts into applause. “Fantastic! Bravo! Hear, hear! I love that story!” he cries, just overexcitedly enough that I’m thinking maybe he should ease up a little on the brain- derived neurotrophic factor.

But April has gotten ahead of herself, and Michael joins in now to take the story back to the moment they met, when April met a creature she’d long since given up for mythical: a grown man—whether straight, gay, or in between—who wasn’t on some fundamental level a dog. Nor was it any natural gift or hard-won emotional insight that made him different. “Before CR, I was, if anything, hornier than most men,” says Michael. “But some people find that when they go on very severe CR, their classic male libido—that sort of aaaargh-there’s-a-pretty-woman-I-can’t-stop-my-neck-from-moving libido—goes down.” And Michael, it turns out, is one of those people.

“I’ve often thought that if you could explain to women that on CR, men will improve their sexual performance but decrease their skirt-chasing behavior so they only have eyes for you, who they’re in love with, women would be like, ‘I’m cutting your calories, honey. Half your dinner tomorrow,’” April resumes. “A 35-year-old who is mature and is interested in a deep spiritual experience but can fuck like an 18-year-old? That’s a pretty good thing.”

Okay, but what about women who don’t share April’s natural attraction to underweight men? Women like my girlfriend, for instance, who was happy enough to see the first ten pounds drop off my calorie-restricted frame but likes the shape I’m in less and less as my weight keeps dropping?

“You might have to change girlfriends,” Paul quips, though it’s not exactly clear to me he’s kidding. He seems quite serious, for instance, as he barrels on into a brief oration on the beauty of the calorie-restricted male physique and the need to rethink our cultural standards of male beauty. “Men are stereotyped and still associated with Arnold Schwarzenegger and that kind of thing,” he complains. “But to be honest, when I see a man like Michael, I think that’s how a man should be. I think he looks absolutely handsome—intelligent, dapper, sexy. It’s a mark of intelligence, of how a great role model should be: slim, bright, calorie-restricted!”

All eyes now fall on Michael, naturally, and for the first time, I get a good look at his hands. And though I’m sure the light must be playing tricks on me, I can’t help thinking that those hands are actually a vivid shade of …

“I know, isn’t it pretty?” asks April. “I love the orange. I call him the Orange One.”

Michael smiles, just a little. “I consume an enormous amount of carotenoids—beta-carotene and lycopene—which are found in foods like carrots, kale, tomatoes,” he explains. “If I had skin like yours, the effect probably would be barely noticeable, but because my skin is an extremely pasty white to begin with … ”

“So wait,” Adam interjects, “you eat so much kale, tomatoes, and carrots that your hands actually turn orange?”

“The focus is health. The constant thought is, ‘How can I pack more nutrition into my calories?’— that’s not something an anorexic is doing. Anorexia is slow suicide.”

“Yes, isn’t it pretty?” April asks again.

And sure, I’m thinking, maybe it is. And maybe if I look a little harder, I’ll eventually see with my own eyes just how pretty Michael’s orange hands really are. But first, I’m going to need a moment to deal with the slight attack of existential vertigo that’s hitting me just now. All evening, I have let the bubbling enthusiasm and essential reasonableness of my guests carry me past the little weirdnesses that go with being calorie-restricted. But the weirdnesses are starting to pile up, and my guests are looking weirder and weirder themselves, like emissaries from a future I’m not sure could ever feel like home: a world where the food grows in vats, where the porn industry just barely survives on government subsidies, where the physically ideal male has the BMI of Mary-Kate Olsen and the skin tones of an Oompa-Loompa.

I take a deep breath then and think, A world where 80 is the new 40. And suddenly, all those little weirdnesses seem quite manageable again.

At which point Michael, having finished his helping of asparagus and Quorn, picks up his plate without a word and does what any normal person who has not eaten a truly filling meal in years would do: He holds the plate up to his face and commences licking it clean. April looks on smilingly, and though I feel another tingle of vertigo coming on at the sight, it passes soon enough.

For dessert, we get a CR-perfect parfait: organic strawberries, nonfat ricotta, flaxseed oil, and hazelnuts. It’s very good, and it’s gone too fast, and as long as we’re rewriting the book on table manners here, I can’t see the harm in scooping out the last bits of ricotta with my fingers. April sees me and frowns, concerned. “You need to eat more. Like right now,” she says, bringing me seconds.

This of course is just the sort of swift correction any responsible CR veteran would apply to a fellow calorie restricter showing signs of manorexia. But with April, there’s a little more to it than that. She’s a woman, for one thing, which the typical CR veteran is not, and that alone makes her more than typically familiar with the feminine cult of self-starvation and its costs. Beyond that, too, she brings a special knowledge with her from her high-school years, spent at the Interlochen Arts Academy—a peculiarly intense Midwestern boarding school lately prominent in the literature of eating disorders, having served as the central setting for the acclaimed memoir of anorexia and bulimia Wasted, by April’s Interlochen classmate Marya Hornbacher.

“I have a ton of survivor’s guilt for being one of the ones who made it out alive, you know? Because so many of my close friends have been down that path,” says April. “When we were in high school, everybody was doing it. Interlochen was a performing-arts school where dancers were graded down for gaining weight. And we all used to think we were fat and be miserable about our bodies. And, you know, when I started CR, there were questions like, ‘Oh, have you gone anorexic?’ ”

“But they are such complete opposites,” April insists. “The focus of CR is health. Nobody here is trying to figure out how to eat less and disappear. The constant thought is, ‘How can I pack more nutrition into my calories?’—and that’s not something an anorexic is doing. Anorexia is slow suicide.”

It’s a heartening distinction, but I soon find myself wondering if there isn’t more truth to it than April herself, perhaps, realizes. For if anorexia is suicide, and the opposite of suicide is to fly from death, then what can its complete opposite be but to leave death behind completely? The quest for immortality doesn’t figure prominently in the official literature of the Calorie Restriction Society, to be sure, but it’s funny what people will get around to talking about toward the end of a good long meal, when the dessert plates stand empty and all the tamer topics have been worked through.

“Kurzweil thinks we will reach actuarial escape velocity pretty soon,” says Don. “What do you think, Michael?”

Michael pauses to collect his thoughts, and while he does, let’s fill in a blank or two. Ray Kurzweil is an occasionally best-selling futurist, given to flamboyant but well-researched predictions about the “transhumanist” century ahead of us, in which hyperbrainy artificial intelligence, fiendishly intricate nanorobotry, genome-twiddling Frankentech, and other incipient techno-marvels combine to reinvent humanity in the image of the machine. Swirling in the midst of it all is the key concept of “actuarial escape velocity,” a transhumanist term for that moment in the acceleration of biomedical progress when, for every year you live, technology adds another year or more to your maximum life span. It’s a tipping point that, theoretically at least, never stops tipping.

“I would like to hope 50 to 100 years,” says Michael, speaking carefully. He’s well aware what kind of weight that his day job, assisting the maverick life-extension theorist Aubrey de Grey, gives his words with people like Don. “Fifty to 100 years,” says Don, chewing thoughtfully on his lip. “That may be too late for me.”

“It may be too late for me,” says Michael. But the truth is, once you accept that actuarial escape velocity is out there waiting for you, a single point in time that marks the gates of immortality, it’s never too late to hope your life will intersect with it—and there isn’t much you wouldn’t do to minimize your chances of missing it by so much as a day. With stakes like that in play, even a lifetime of hunger seems a small price to pay.

And in the end, after the dishes are all cleared and Adam and I have waved good-bye to all my calorie-restricted dinner guests, it’s the adrenaline burst of that final proposition that still buzzes in me. The sure-bet benefits—the lowered risks of cancer, diabetes, heart attack, the very probable addition of several years’ peak performance to my sex life and my mental life—these all sweeten the pot, to be sure. But I’d be lying if I said it’s not the straight, long shot at immortality I have uppermost in my mind as I shut the door, walk back into the kitchen, and turn to Adam, one eyebrow raised, for confirmation that a calorie-restricted life might be worth living.

I’m just about sold myself. But Adam is an independent observer, his judgment far less likely to be compromised by traces of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, and he has seen all he needs to see of CR. He’s heard the many arguments in favor of Calorie Restriction and the few that carry any weight against it; he’s met some of its smartest and most likable practitioners. He’s even tasted and declared “not bad” the best of its cuisine.

“So, whoa,” says Adam. “I have got to say that that was probably the blandest-tasting meal I’ve had since, like, ever.”

I’m confused. “But you said—”

“I was being nice.” An awkward silence reigns until at last Adam puts his hand on my shoulder, looks me in the eye, and says, “Dude. It was bad.”

Late in the morning on the first day after my dinner party, I awaken hungry, go downstairs, walk into the first McDonald’s I encounter, and consume, for breakfast, an entire Quarter Pounder with cheese and a 12-ounce chocolate triple-thick shake. Later, at the cocktail hour, I drink several Cuba Libres and eat cheese-laden canapés to my heart’s content. For dinner, I stop in at Katz’s Delicatessen on Houston Street and ingest one half of a two-inch-thick pastrami on rye, half a corned-beef sandwich just as massive, several pickled tomatoes, and a cream soda, and only after eating a slab of chocolate-coated Häagen-Dazs ice cream on a stick at bedtime do I begin to feel the first, light pangs of queasiness. For the first time in 63 days, I end the day without the slightest idea how many calories I ate or the least desire to know.

You would think it would have taken more than a few unkind remarks about Quorn to cancel my date with a calorie- restricted destiny, and you would be right, of course. Adam’s skepticism got me thinking, is all—not so much about how the food tasted to him as about how the whole evening must have looked to him, and for that matter, how it might have looked to me just a few months earlier. The slightly messianic tint to Paul McGlothin’s every utterance; the casual yet total confidence with which Don and Michael had discussed their prospects for eternal life on Earth, like two born-again Christians guessing at the precise date of the Rapture. I liked these people, I really did. But in the end, I made my way home that night with the growing sense that I had just come closer than I ever had to falling down the bottomless black hole of cult membership.

I know: What was I thinking? But do you really need to ask? The workings of a heart and mind like mine are no mystery. I’m your average midlife secular professional—reasonably well adjusted, as the profile goes—a little tightly wound, but aren’t we all? Like the tail-end baby- boomer I also am, I grow more intimate each day with the fears of mortality already gripping the rest of my generation, and lacking spiritual faith, I am perhaps inordinately susceptible to scientific promises of longer, healthier life. I’m of the generation that made marathon running a popular pastime, for God’s sake, so fleshly discomfort in the name of self-involved achievement is a surprisingly easy sell. Throw in a promise that any undue pain and suffering will be masked or compensated by a psychic well-being possibly chemical in origin, and the deal is just about clinched.

I won’t belabor the point: Just take a good look around your neighborhood, your place of work, your therapist’s waiting room. Take a good look in the mirror maybe, too. That ought to be enough to tell you CR’s growth from cult to subculture to fact of mainstream cultural life is not so unimaginable. Yes, CR flies in the face of common sense, but it’s got the preponderance of scientific evidence on its side. Yes, it’s a little crazy, but the crazinesses it requires are only those already endemic to our age and area code. And yes, by any objective standard, the food is lousy, but believe me: Starve yourself long enough and even a tofu-coffee-macadamia-nut-and-flaxseed smoothie becomes ambrosia.

So if you’ve read this far and still think you could never, ever, do what my five dinner guests do to themselves every day, don’t kid yourself. I’ve seen the future, and it’s hungry.