H ey, hey, superstar!”

L.A. Reid, chairman of the Island Def Jam Music Group, shouts to Ryan Leslie, as a man with a video camera trails behind them.

Everywhere he goes, Leslie is filmed. This is because he pays someone to film him.

Leslie—wearing metal-studded sunglasses and a thicket of gold chains—struts into Reid’s cavernous midtown office. Reid’s assistant shuts the door behind them with a polite smile, which leaves me waiting in his anteroom with Leslie’s full-time videographer (a do-rag-wearing 22-year-old named Daytona, who films every waking moment of Leslie’s life) and his publicist (an unpaid teenager named Brandon, who wears sunglasses that look a lot like Leslie’s but are clearly much, much less expensive).

Holding out the camera, Daytona hits rewind. “Can you hear where L.A. says, ‘Hey, hey, superstar’?” he asks Brandon. Daytona then presses his face back to the eyepiece and begins to review the other shots he’s captured this afternoon. At the end of the day, Leslie usually edits down Daytona’s footage into a highlight reel that he posts on his Website. (It’s not clear to me what today’s highlights will look like—in the course of the hour-plus I’ve spent with them so far, Daytona has filmed five separate elevator rides.)

Leslie flew back just last night from two weeks in Europe. He’d been guiding Cassie, his breakout R&B creation, through a whirlwind promotional tour. (Relevant Cassie facts: She is 20 years old; she is a former fashion model; she is of mixed Mexican, African-American, West Indian, and Filipina ethnicity; she is atomically sexy.) Leslie met Cassie at Marquee last year, and soon after adopted her as a pet musical project. He wrote several songs for her and produced them on his own. He did all the recording himself, with a few keyboards and a desktop Macintosh, in the living room of his Harlem apartment.

This past August, more than a year after it was recorded, and to the shock of the music industry, Cassie’s “Me & U” went to No. 3 on Billboard’s singles chart. It reached No. 1 on the R&B/Hip-Hop singles chart. And so—because Cassie’s success came out of nowhere, owed very little to a voice the Washington Post called “Janet-Jackson-after-20-flights-of-stairs thin,” and was the product of not just Leslie’s musical vision but also a masterful MySpace campaign he orchestrated (with no corporate backing, until Sean “Diddy” Combs, whom Leslie had previously produced songs for, spotted the burgeoning hit and offered a distribution deal)—music executives’ fevered hope is that Leslie might re-create this Svengali-like miracle. “The label CEOs all want an audience,” he says. “They’re courting me. It’s insane.” Today is also Leslie’s 28th birthday.

At this point, I’ll ask you to rewind back through half of Ryan Leslie’s life span. Erase from your mind the current incarnation of Leslie (a.k.a. “R-Les”), in those oversize shades, gold chains, and leather jacket with epaulets. Instead, envision R-Les at 14 years old, attending public high school in Stockton, California. His parents, Salvation Army officers who frequently relocate for work, are planning to move again. Rather than switch to his fifth high school, Leslie decides he’ll start college after his sophomore year.

He takes the SATs—and gets a perfect 1600 score. He writes letters to Harvard, Yale, Stanford, and other universities, explaining his unique situation, and is accepted everywhere (save for Stanford, which was concerned that he wasn’t socially mature enough). In the fall of 1994, at the tender age of 15, Leslie begins his freshman year at Harvard. He intends to go premed.

Leslie has a musical background, playing cornet as a child in the Salvation Army band. (He later switched to piano because his overbite made it difficult to get proper embouchure on a brass instrument.) At Harvard, he quickly joins the Krokodiloes, an a cappella group. But it’s when a friend plays him a Stevie Wonder CD freshman year that Leslie suddenly saw a new future for himself.

“I became obsessed with him,” he says. “I wanted to chase that man’s career.” And thus began the transition from premed Poindexter to R&B Romeo.

Leslie becomes a constant presence at the on-campus recording studio. Fellow student Chiqui Matthew remembers Leslie making beats at every free moment. “He was on a different level of intensity. Most of us were pretty realistic—we’re Harvard students; this music stuff is fun, but this isn’t the future,” says Matthew, who now works with credit derivatives at Goldman Sachs. “But Ryan always had a ten-year plan about how he was going to take over the music industry.”

While still a student, Leslie begins producing tracks for local Boston artists. Meanwhile, R-Les was beginning to mold his own image, too. “He had this pseudo-sexual, thugged-out Lothario thing,” says Matthew. “I never really bought it. He seemed more like a music nerd to me.”

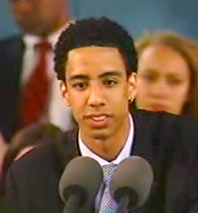

Leslie graduates in 1998, at 19 years old. He delivers the prestigious Harvard Oration at the commencement ceremony, looking extremely clean cut in a blazer, tie, and one tasteful earring. The speech is a rather hammy affair, complete with preacher cadences and an interlude of soulful a cappella crooning. Leslie proudly announces his plan to pursue a career in “the arts.” There is a video clip of this speech on Leslie’s Website.

A few years later, after bouncing around the Boston music scene for a while, ultimately moving back home with his parents (then living in Phoenix), he wangles a music internship in New York and comes under the tutelage of Combs. A few years after that, “Me & U” became a sensation. And now R-Les is one of the hottest record producers in the world.

Even as Ivy Leaguers invade and occupy all sorts of new realms, from the waves of Harvard Lampoon veterans who make our lowbrow comedies to the laptop-wielding sabermetricians who’ve taken over baseball’s front offices, hip-hop remained one of the few industries immune to the beguiling powers of an elite degree.

At the same time, there’s always been a striving element to the classic hip-hop success story. Guys like Jay-Z, Pharrell, and Diddy are endlessly bragging about how hard they work. How many entrepreneurial projects they’re juggling. And what could be more striving than a 15-year-old with perfect SAT scores begging to start university early? What on this earth could exhibit more hustle than a high-schooler with eyes on Harvard?

Given how seamlessly the hip-hop and Harvard mentalities entwine, it’s almost surprising it hasn’t happened before. But Ryan Leslie represents a new archetype: the Harvard hip-hop hustler.

From the waiting room, which contains a piano, an acoustic guitar, and a six-foot-tall plaque of Mariah Carey astride a pile of platinum records, we can hear Leslie playing “Ditto”—a forthcoming, insanely catchy Cassie single—over the sound system in L.A. Reid’s office. When it’s done, Leslie plays Reid “Like That,” a track he recently produced for the 15-year-old singer JoJo with the refrain “Do me like that.”

This is all part of an audition for a producer gig for Island Def Jam. Ever since the Cassie record blew up, Reid (Jay-Z’s boss and a legend in music circles) has been eager to meet the man behind the megahit. He’s even told Leslie that “Me & U” is his “favorite song right now.” Before Cassie, it seemed possible that Leslie was destined to live out his career as a mid-tier beat-maker—languishing on various record-label payrolls, producing forgettable hip-hop songs for forgettable artists. (New Edition’s non-comeback single “Hot 2nite”? That was Leslie.) But a hit changes everything.

Across Reid’s waiting room, Leslie’s intern, Brandon, furiously thumbs his BlackBerry. Brandon first became aware of Ryan Leslie on MySpace, where he kept seeing Leslie’s avatar cropping up as a “friend” on the pages of various fans. Brandon became intrigued by the jet-setting, celebrity-schmoozing, hip-hop-mogul lifestyle Leslie’s own MySpace page portrayed.

“He impressed me,” says Brandon. “I thought, This guy’s a really good entrepreneur.” One night this spring, at about three in the morning, Brandon sent a MySpace message to Leslie asking for an internship. Leslie immediately replied with his cell-phone number, and they had a conversation right there in the wee hours. Brandon’s been Leslie’s unpaid publicist ever since. “It’s weird, if you think about it,” he says.

Leslie’s thoroughly modern marketing theory is that by providing fans with a daily behind-the-scenes look at his life (full of self-promotion and name-dropping, of course—video clips on Leslie’s Website show him mingling with Diddy, Snoop, Usher, and Quincy Jones), he can make them feel they’re riding shotgun on his fabulous hip-hop dreamquest. “The secret is that I pay them some attention,” says Leslie. His is a nerdy, diligent kind of stardom.

He has clearly mastered the art of MySpace viral promotion. Three weeks after he posted “Me & U” to the site in November last year, 60,000 people had made Cassie’s song their MySpace background music. Then it snowballed. “He had 10 million in audience before the Atlantic promotions people [from Diddy’s parent label] even got involved,” says music executive Tommy Mottola, the former president of Columbia Records (who launched his former wife, Mariah Carey, to megastardom).

Never before had the MySpace hordes been so skillfully manipulated. Leslie parlayed all those kids’ asking Cassie for an “add” into a label deal and a national radio hit. Though most artists are savvy to MySpace these days, the nowhere-to-No. 1 ascent of “Me & U” was unprecedented.

“This is not just some kid making beats,” says Mottola, whom Leslie acquired as a mentor after he came to New York. “When you add into the mix that Ryan is a Harvard graduate, I think he’ll become an entrepreneur on a different level. Something very big. Probably having to do with the Internet.”

As with most Harvard grads (and hip-hop moguls), Leslie’s ambitions are predictably boundless. He’s trying to jump-start his own singing career. He’s described a plan for a new type of online bidding site (he got the idea from an article he read in Business 2.0) and also hopes to market a basketball sneaker under the brand name B-Unique. When Leslie first hands me a prototype of the shoe—a leather, old-school high-top—I feel the exact opposite of surprise.

Leslie and L.A. Reid met for over an hour, which presumably is a good sign but has also made us late for our next appointment. We quickly head to the Fifth Avenue offices of J Records, where Leslie is scheduled to meet with label executive Steve Ferrera.

Ferrera hopes Leslie will write and produce tracks for the debut album by Katherine McPhee, last season’s American Idol runner-up. When Leslie arrives, Ferrera hands him a picture of McPhee. “As you can see,” says Ferrera, “she’s obviously extremely hot looking.” (Leslie nods.) “If I put a piece of shit on a CD, it will guarantee a million sales,” Ferrara continues. “But if we get this thing right, it’s Kelly Clarkson. It’s 15 million records.”

Ferrera slides in a CD of a demo song McPhee has already recorded. “I want to see how urban she can go. Believably.” The music begins. “This song is called ‘Open Toes,’ ” shouts Ferrera over the deafening beat. “It’s about hot shoes with open toes,” he yells. The only lyric I manage to make out goes “ ’Cuz I know that boys, they like these open toes.”

This is the real Tin Pan Alley side of the business. A new star gets designated by the label and then later, someone has to write the songs for her. In this case, Ferrera hopes to set up McPhee with Timbaland (perhaps the most lauded hip-hop producer of our time, who recently lent his talent to the new Justin Timberlake album), Babyface (who twice set the record for longest run at No. 1 on the Billboard singles chart), and Leslie. All three will end up working with McPhee; Leslie’s doing two songs. “The biggest thing to come out of that meeting,” Leslie tells me later, “is that apparently I’m now getting put on a level with those guys. That’s huge.” A producer like Timbaland can command up to $250,000 for a single track. “And if Timbaland can put himself on the Justin Timberlake record and the Nelly Furtado record, it seems like I could put myself on this record and raise my profile.”

In the car ride leaving the meeting, I ask Leslie what type of song he thinks Ferrera expects from him. “At this point, I have a pretty signature sound, so when they call me, they know what they’re getting,” he says. “It’s like the fashion houses. Cavalli will have ripped pants and wings and all that. Gucci will be more conservative. I equate myself with Dior—it has rock-star appeal, but it’s still very well tailored and well respected. Prince is more like Cavalli. If you have that kind of musicianship, you can be wilder. I stay in my lane.”

Cassie’s “Me & U,” which Ryan Leslie wrote, produced, and recorded in his living room, became a No. 1 hit. Music executives’ fevered hope is that he might re-create this Svengali-like miracle.

“It’s very simple and direct, and that’s why it cuts through on the radio,” says Chris Richards, a Washington Post music writer who says Cassie’s album is his favorite this year. Where Timbaland samples crying babies and Indian tablas, Leslie puts pretty synth-pop melodies in the foreground. “I wanted to use some trancey dance sounds that aren’t usually found in R&B,” Leslie says. It’s less like a wild creation and more like the grinding of a premed gunner.

On the European tour she and Leslie have just returned from, Cassie did an interview with a Swedish radio host who asked her about “the electrominimalistic sound of Ryan Leslie.” The Swede then began to ask how much of a role 9/11 had played in informing Leslie’s aesthetic. Cassie—a 20-year-old who, prior to recording these songs, had spent time modeling for Delia’s clothing catalogue—was not completely comfortable with this line of questioning.

Mottola has a more succinct analysis. When asked what first caught his ear about Leslie’s songs, he quickly answers, “They sounded like hits.”

The chauffeured SUV speeds north into Harlem. Leslie’s on the phone with a tailor in Boston, ordering several pairs of trousers. (“I have time to revamp my entire denim collection.”) When he’s done with the tailor, he calls a dance studio, trying to book time for a rehearsal later tonight. He’s in training for a video he wants to make for one of his own songs, “The Way That U Move,” an up-tempo dance number that showcases Leslie’s croon, which, while serviceable, is more Cassie than Carey. He plans to self-fund the whole thing, shelling out about $100,000 to hire the video director Ray Kay, who did “Me & U.” I ask him how good a dancer he is. “I’m just trying to polish my natural talent,” he says. “It’s like a diamond—it’s already a diamond, but if you polish it, then it really pops.”

In the time I’ve spent with Leslie, he has revealed only two interests beyond his life as a musician and an entrepreneur. The first is buying custom-made clothes. The second is watching DVD biographies of industrial-era titans like John D. Rockefeller. Ask him to speak contemplatively, and he’ll quickly hide behind platitudes or shift the discussion to talk about the next goals in his sights. At these times, he pitches his tone less to the person sitting across from him and more to some sort of vast audience in his head. As though he were speaking into Daytona’s camera and dispensing advice to fans, like in his video-diary entry titled “A Word About Good Representation.” (This tone can sometimes contrast sharply with his surroundings: He once gave a lofty speech to me over a meal at Jimbo’s Hamburger Palace—the cash-only greasy spoon on Lenox Avenue where Leslie eats almost all his meals.)

When the car pulls up at Leslie’s apartment in a brownstone on 136th Street, Leslie waits for the driver to walk around and open the door for him. He steps onto a littery curb next to a leaking fire hydrant. Inside his apartment, there are suitcases and clothes strewn across the floor and takeout-food boxes lying open on the counters. Though Brandon tells me of Leslie’s success with the ladies (“one with a Dior campaign and the other a Victoria’s Secret Angel”), the place could use a woman’s touch.

In less than 45 minutes, Leslie expects a singer named Linda Király to show up at his apartment for their first recording session. Király is 23 years old and has lived in Hungary for the past six years. She had a No. 1 album in Hungary and played the lead in Phantom of the Opera there. She has a five-octave range and truly massive breasts, which is why some of the high-ups at Universal Music think she might be the next Mariah Carey. When I ask Leslie what he’s written for Király to record when she shows up, he says, “Oh, I don’t have anything written. I’ll just work something out once she gets here.”

This stunned me. It turns out hit songs are often written, in a soup-to-nuts collaboration between artist and producer, in about an hour and a half. And indeed, it’s only after Leslie meets Király and her manager (whose primary job seems to be forbidding the pudgy Király from eating anything) that he sits down at his Macintosh and begins to program some initial drum tracks. After the rough beat is laid, Leslie begins to layer in a soft, balladic piano sequence. He then adds hand claps. A high-hat pattern. An echoey synth wash. (Daytona is filming every moment, including long sequences when Leslie is just clicking his mouse around the computer screen.) “Is that in your range?” he asks Király. “I want to fit it to your timbre.”

She’s stepping over to the microphone now, putting on headphones. Leslie types out some lyrics (he’s thinking them up on the spot) in a huge font on his laptop monitor and holds them up for her to sing. “You’re all I’ve ever knoooooown,” she coos. “More than I’ve dreamed of. I should be happy now. So why do I feel I need … time on myyyyyyyy own.”

Leslie is smiling. You can see it on his face: He’s gone into a different brain-wave pattern; he’s in the midst of a creative burst. Király is belting out the verse again, interweaving at least three of her five octaves through Leslie’s music. Here in this tiny Harlem room, to my ears, the song sounds achingly beautiful.

But Király isn’t happy with the direction of the song. She’s getting tired and cranky. Her manager decides to come back tomorrow to try again.

“This girl sounds like she’s singing opera over the track. With Cassie, I swear I’d have this record completely written and recorded by now,” Leslie says with a sigh when Király leaves. “I think I’m over being a producer,” he says. “I should just be an executive-slash-visionary. The Puffy formula.”

Brandon, Daytona, and Leslie sit around in the studio for a few more hours, with Daytona filming their conversations and the occasional phone calls Leslie makes. After a while, Leslie starts D.J.-ing. The room comes to a reverential hush when he hauls out (clearly not for the first time) the Thriller special-edition CD, which includes additional audio tracks on which Quincy Jones narrates anecdotes about shaping Michael Jackson’s demos into full-bodied, hip-shaking dance hits.

When the actual songs come on, Leslie gets to his feet and begins to dance like MJ, his knees and ankles wiggling around. He points at the speakers during a funky synth break and shouts, “That’s the genius of Quincy Jones! Insane!!” He holds his hands high in the air, palms up, and spreads his fingers as though releasing imaginary doves. Daytona puts in a new camcorder tape and starts rolling.