It would have been a hard couple of months, even if she had been eating.

Judith Regan loves to fast. She likes the high you get, the way it makes you feel clear, intuitive, even telepathic, transforming your skin into a baby’s and launching your energy level into the stratosphere. Says Natalia Rose, Upper East Side detoxing guru, “She loves eating really clean. When I tell her my big picture of how I want everyone to understand their connection to the light, and by healing each other we heal the world, she totally believes that.”

The first week of November, Regan and a couple of the women in her office started a 21-day fast, so through all of the O.J. madness, the only nutrition she had every day was an infusion of berry drinks, enzyme shots, hot tea, live juice, and a once-a-day treat of soup—a mélange of carrots, sweet potatoes, and spinach puréed in the Cuisinart. She was not allowed to chew—anything. Every night at 10 p.m., she drank a foul-tasting shot of aloe and made a hot tea before she went to bed. She was famished.

Even after everything happened with the TV show and the book—after tabloid headlines excoriating her for consorting with the most notorious murderer of the past quarter-century; after Rupert Murdoch and her immediate superior at HarperCollins, Jane Friedman, let her twist in the wind; after even she herself had realized that it was best not to go forward with the book—she wasn’t going to abandon her diet. She went back to Los Angeles, to her life as a “hotel slut,” as she liked to call herself, in a twenties hotel on Sunset Boulevard, and tried to focus on what was important: moving on. The loss of sales from the O.J. book was a huge financial hit for her imprint. She needed to acquire books, immediately, to make up for it—what was the “next next thing,” as she liked to call the type of projects she was looking for? No self-pity! As in the rest of her life, she had declared war on pathetic, quotidian self-pity, the kind of classically feminine shame that keeps women up on the phone at night whining about ex-lovers, that keeps losers in the cycle of playing a losing game, that stops human beings from evolving into legends, as she had, transforming herself into the biblical Judith who cuts men’s heads off in one fell swoop—a heroine.

In her office the day before she was fired, she had a meeting with Anna David, the author of the book Party Girl—You’re so gorgeous you should be on the cover of your book!—and chatted in the corridors with some of her staff: One of the moms told her about her ex-husband, who seemed to be ignoring their kids at Christmastime and reneging on special presents. “Of course he doesn’t have to get them presents,” she fumed. “He’s a man—the only thing they’re good for is semen. They’re inseminators! That’s all they are!”

A stray male walked down the hallway.

“Not you,” she called after him, dissolving in laughter. “Every man except you!”

She went home and drank her tea with lemon. She wasn’t feeling all that bad. The next day, before a sales conference, she got on the phone with Murdoch in-house counsel Mark Jackson. She said some repulsive things, telling him that she felt there was a cabal in the company against her—as later reported, a Jewish cabal—but this is how she talked to Jackson sometimes, when they were arguing, so she didn’t think much more about it.

And then—zzzzttt. Her computer went down. In fact, the server for all the office computers went down. A woman from sales ran down to editors’ row: Her boyfriend, a manager at Book Soup, had called to say that a HarperCollins rep was saying Regan was fired. Everyone was shepherded into the conference room, where a long-suffering ReganBooks deputy made the announcement: Judith has been fired, you all have to remember your confidentiality agreements, please don’t talk to the press, and don’t contact Judith, who has been escorted from the building.

An editor interrupted: “Judith hasn’t been escorted from the building. She’s in her office, on her computer.”

A few of them ran down the hall, and there she was, the long chestnut hair streaming down her shoulders, the arched eyebrows and pink-lipsticked mouth, fiddling with her keyboard to get the computer to work. A roasted-pepper-and-mushroom sandwich sat before her, half-eaten.

They peered in.

“So I’m eating a sandwich,” she said, shrugging. “My blood sugar is low. I’m allowed to eat a sandwich. Why are you staring at me?”

The termination of Regan’s employment at HarperCollins may be one of the only times in Regan’s life where she hasn’t had the sandwich and eaten it too. Regan is 53, with twenty years in the book business, twelve of them at HarperCollins. Few publishers can rival the success of the Irish-Italian mother of two from Bay Shore who once worked at the National Enquirer: Although HarperCollins does not provide such figures, some put ReganBooks in years past as accounting for as much as $120 million a year. She has a flamboyant way of characterizing things: In the wake of her firing, she told friends she was escorted out by a sheriff, when in fact the guards waited for her while employees scurried down the back stairs with some of her personal effects. “They sent men with guns to the office!” she told friends. “Well, you know, darling, I would go out in style.”

Regan moved to L.A. in hopes of becoming an even bigger star than she was during her Howard Stern and Rush Limbaugh days. She’d published huge-selling books by both Stern and Limbaugh, as well as by Jenna Jameson, New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey, dozens of others, button-pushing tell-alls that often found their way onto the best-seller list. All the while becoming locally famous as one of the toughest, most volatile bosses in New York City, which is saying something. But celebrity tomes weren’t going to work for her in the same way that they used to, she’d started to realize. If the O.J. book and TV special had worked out, she might have been heralded as a multiplatform genius; she would’ve been positioned perfectly to become a kind of Martha Stewart, the face of her own publishing empire. With Martha, there was a veneer of the traditional feminine homemaker over the steely ambition, but with Judith, everything was on show, and what a show it was. Regan had been known to scream, “I have the biggest cock in the building” from behind her desk. O.J. was meant to be her coming-out in Los Angeles, her clarion call to the entertainment industry. “Before the book was even announced, back when it was a secret, Judith was telling people it was the book of her career,” says a friend.

The O.J. project also promised to give her something else she wanted: a new relationship with News Corp. chairman Rupert Murdoch. Regan had a complicated, often paradoxical relationship with her corporate overlords. Murdoch had always respected Regan’s commercial instincts, yet, as ReganBooks made up an infinitesimal portion of News Corp.’s bottom line, she wasn’t exactly in his inner circle. He wasn’t thrilled when her dalliances with former police commissioner Bernie Kerik made the news, and in fact was a little grossed-out before that when Kerik sent on-duty cops to make midnight visits to Fox employees after Regan complained that someone had stolen her cell phone on a Fox TV set. He sometimes left her off the list of conference invitees, like the one for 250 executives in Pebble Beach, California, last year. They used to talk more, once upon a time, but in 1997 Jane Friedman came in as CEO of HarperCollins and Regan was not entirely sure that the two things didn’t have a lot to do with each other. Regan had been hired directly by Murdoch before News Corp. added Friedman as worldwide CEO. For an Ayn Rand–ish superwoman like Regan, it was hard to think of Friedman as more than a bureaucratic figurehead, the person who signed off on her annual budget, an impediment at best. (Regan and Friedman declined to be interviewed for this article.)

Although their egos aren’t so far apart, in other ways, Friedman and Regan are opposites. Friedman is careful to keep her public and private lives separate. She lives in an understated apartment near Sutton Place, has two grown sons from her first marriage, and until recently lived with Jeff Stone, a tattooed, gray-ponytailed brand-identity consultant responsible for the “Chic Simple” series and such titles as Dr. Steven Lamm’s The Hardness Factor. For his part, Stone once told Vanity Fair that men had golden guts and Regan had a “golden vagina.”

Unlike Regan, whose publishing model is based on a strong leader and few minions, Friedman is a believer in the team concept. She rose from a Random House Dictaphone typist in 1968 to become a publicist. Friedman has long been in the habit of making bold claims about having reinvented the publishing business. She likes to say that she conceived the “author tour and audio books,” which may be overstepping (Mark Twain, after all, traveled across America), but her success with modern tours, beginning with Julia Child’s cooking extravaganzas, and her achievements as the founder of Random House Audio Publishing, are notable. At Random House, she served as an indispensable No. 2 to both Sonny Mehta and Bob Gottlieb and executed successful campaigns for Michael Crichton, a close friend, and fluke best sellers like In the Kitchen With Rosie and I Was Amelia Earhart.

At HarperCollins, Friedman and Regan circled each other warily. Friedman realized quickly that their two successes would be intertwined—within a few years, she had doubled the company’s profits, thanks in part to Regan’s frontlist. (In some years, Regan had as many as fifteen best sellers and five No. 1’s.) Employing Matthew Hiltzik as HarperCollins’ corporate publicist, Friedman clearly relishes her power. At one Take Your Kids to Work Day, she began a speech with, “What do the letters C-E-O stand for?” With Regan’s sexiness, her Midas touch, and her penchant for the limelight, Friedman worried that she could be a prisoner of Regan’s success, and she knew she needed to keep Regan onboard by making her feel like she was in control. But she also wanted her in her place. It was this complicated dynamic that underlay the violent unraveling of the O.J. project.

“Jane likes to have everyone stay on the reservation, and Judith was in her own galaxy, far, far away,” says a HarperCollins editor. Nor does she tolerate people speaking to her in impertinent tones of voice, the kind of tones that Regan is capable of using. Over time, Regan became convinced that Friedman was standing in her way. For all of her bravado and over-the-top personality, Friedman doesn’t like confrontation.

Among many employees, there was a sense that you were either with Regan or you were with Friedman—Regan was fond of yelling exactly this sentiment, too, when she felt someone had disobeyed her command. “They’re two really needy women who can’t be wrong,” says one HarperCollins editor. Though the two women did not argue much in person—they were usually cordial, even saccharine to each other—by many accounts their relationship became one of legendary horror. “They were blinded by their hatred of one another,” says a News Corp. executive.

A few years ago, after I wrote a story for this magazine on the then-burgeoning Internet-dating scene, timid young editors from ReganBooks began to call to ask if I wanted to write books on various topics, such as the man with the biggest penis in the world. Um, no. Regan asked me to lunch, and we instantly bonded. To a woman, there’s something enticing about Regan’s anti–plastic surgery, pro-sex feminist stance, mixed with a She-Devil-ish anger at the power men have in the world (even though she sometimes expresses it by saying that she’s going to eat their testicles). She told me that I reminded her of herself when she was younger and that she could give me a great job, show me the ropes, take me on a tour—perhaps one day I would even become as powerful as her. “I used to be a writer, too, but I wanted to do more in the world—don’t you?” she asked. Yes! I told her I was worried about managing a career and a family, and it seemed like I could have only one or the other. You can do it all, she said—don’t let anyone trick you into thinking it’s a choice. Wow. Aren’t you sick of playing by men’s rules, having male editors, writing about what men want you to write about? she asked. She was building her own gang, her own posse, to take on the publishing industry, and I was going to be her capo. We had to make our own group, she said, like the Jews.

Somehow, this didn’t make me run screaming from the restaurant (I am married to a Jew, for the record). I think I took it as a joke at the time, plus, as many of her supporters have pointed out in the wake of the scandal, she says so many crazy things in conversation that such statements don’t sound like ugly hatemongering coming out of her mouth. Anyway, I didn’t go work for her, although we delved into it further, and though she has always been kind and delightful when I’ve seen her, when I hear what employees have to say about her—usually assistants—I’m pretty glad I didn’t. Usually, they start the conversation by screaming, “She’s fucking crazy! She’s a crazy bitch!” And “It’s really sad. If she had the trust gene instead of the paranoid gene, she could be the Oprah of publishing.” And “There were a bunch of assistants sitting in one small area, and Judith would call them cunts who only had a job because of her hard work.” And, perhaps most viciously, “She’s just afraid she’ll end up back in Long Island someday.”

And yet. Judith’s friends speak of her with unmistakable fondness, even associating her profane cast of mind with her gifts. “For Judith, prurient things are really part of the world, and if we pretend otherwise, we’re fooling ourselves,” says Kate Saltzman-Li, a professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara and a friend for 35 years. “That’s the world, and you talk about it as it is—there’s good parts and sex parts and bad parts, and each is significant to our lives.”

She was a master seductress of her authors, as well. “There are a lot of urban legends surrounding Judith, mostly unflattering, but that’s not the Judith I know,” says best-selling ReganBooks author Wally Lamb. “I feel sad more than anything else because people have such a one-dimensional picture of her.”

The HarperCollins narrative of Regan’s fall begins in earnest at least four years ago. Regan’s staff had more than doubled, and she was going through assistants and editors like wildfire. “In the beginning, we were not really aware of the impact of her management style,” says a HarperCollins HR executive. “Then there was a progressive change—almost an intervention—on the company’s part.” Several executives were assigned to work as coaches and advisers with Regan, hoping she could focus on the creative side of things and leave the day-to-day management to other people. “A lot of executive time was spent working very closely with her on things that executives at that level wouldn’t ordinarily do with other people,” says the executive. (Regan’s lawyers deny this arrangement existed.) But things got much worse when, in April 2003, an employee complained about a story Regan told in the office about an incident where mezuzahs in her apartment building were pulled down and replaced with dollar bills. (According to Regan’s lawyers, as well as accounts in Regan’s acrimonious divorce proceedings, it was her husband who’d boasted of pulling down the scrolls.) Human Resources began an investigation and found multiple employees who had taken offense on account of their race, religion, and sexual orientation. A meeting was called. “Her response was to say, ‘I’m outrageous, I’m provocative, people are babies,’ the same responses she always makes,” says an executive.

Regan believed that the quality of some employees who were sent to her by HarperCollins was so low that it almost constituted sabotage. One executive says that they told prospective employees to research her background before committing to working with her. Conditions in her office were not great. “She had water puddles in the office, mold, no A/C for a month in the summer, and in the winter it was so boiling hot you couldn’t think,” says a ReganBooks author. “I was shocked, honestly. It was almost like they were mind-fucking her.”

In the summer of 2003, HarperCollins and Regan agreed to create an associate-publisher position who would oversee the staff, enabling Regan to concentrate on acquiring and creative oversight. But she couldn’t—or wouldn’t—let go. Then, HarperCollins created an HR director, usually responsible for staffs of business units with about 400 employees, expressly for the twenty-odd ReganBooks employees.

Regan had long been after her superiors for permission to move to Los Angeles, where she was convinced she could find all sorts of creative talent she couldn’t find in New York. It also meant she would be out from under Friedman’s thumb, and with a chance to be even more of a celebrity in her own right. The company looked at it this way: She would invite certain staff to move out to L.A. with her, and those who agreed were doing so voluntarily and freely, so they probably weren’t having issues with her, and the staff who remained in New York would no longer be managed by Regan day-to-day. It was win-win.

Judith Regan may be a loose cannon, but this was far from the case with the O.J. book. Rupert Murdoch himself signed off on it. Regan received a call from Simpson’s manager in February 2006, asking if she would be interested in O.J.’s story. Coincidentally, she was going to see Murdoch at a book party that evening. They had a cursory conversation, and she explained that Simpson’s share of the proceeds would be going not to O.J. but to his kids. Murdoch thought it sounded like a viable project and congratulated her on it.

Friedman saw the project as a gigantic mound of cash piled on her bottom line. “There were two secret books at HarperCollins in 2006, and we asked, ‘Are they worth it?’” says a HarperCollins editor. “Jane said that one of them was not that big a deal, but the book with Judith was going to be huge.” Mark Jackson, Murdoch’s in-house counsel, made the deal for about $880,000, put into a third-party trust for Simpson’s children.

Judging by the book, which recently has begun to leak out, the only one who at first wasn’t in harmony with the O.J. project was O.J. himself. Like many a criminal before him, he had an urge to confess that he then became deeply conflicted about.

In the book, what Simpson wanted to talk about, for the most part, was his relationship with Nicole Brown, starting all the way back when he met her in 1977, the night after he separated from his first wife, at the Daisy on Rodeo Drive. Simpson’s self-pity would be comical if we didn’t know the gruesome ending. Nicole was always a problem, Simpson said, from the day they moved in together—he writes, “The fact is we still weren’t married, and I couldn’t go a week without hearing about it: Didn’t I love her? Didn’t we have a future? Couldn’t we have children now, while she was still young enough to enjoy them? These little discussions often ended in arguments, and I absolutely dreaded them. Nicole had a real temper on her, and I’d seen her get physical when she was angry, so sometimes I just left the house and waited for the storm to blow over.”

The two of them fight and break up, have sex, and get back together about 25 times in the book, in between times when he beats her and explains it away. They go on vacation—“Anyway, we got to Cabo and I hit the links and I forgot all about my problems—golf is pretty magical that way.”

Aren’t you sick of playing by men’s rules? Regan asked. She was building her own gang, and I was going to be her capo. We had to make our own group, she said, like the Jews.

His delusion gets more severe as the book proceeds:

“One year before the murder, Nicole pretty much began stalking me. She’d drive by late at night, and if Paula’s truck wasn’t out front she’d ring the bell.

“After we made love, we’d talk. ‘My therapist says that I like to be angry,’ she’d say.

“‘Yep,’ I said.

“‘She says that I look for trouble because it makes me feel alive,’ she explained. ‘We’ve been trying to figure out where this comes from, so we’ve been talking a lot about my childhood.’”

The book is an unsettling and fundamentally dishonest memento of a strange moment in America, rather than any kind of confession. Nevertheless, Regan insisted on titling the book I Did It, but Simpson’s lawyers objected. They finally settled on If I Did It.

Though neither Friedman nor Regan had seen the book, corporate frenzy over the project grew steadily. Originally, Regan wanted to release the book over Super Bowl weekend, but Fox TV wanted to broadcast the show she’d planned to accompany the book during sweeps week.

Regan decided to conduct the interview herself after Barbara Walters pulled out of the deal, with ABC paying a $1 million kill fee. Once Regan cut the deal with Fox, she began to get excited over her role as interviewer. She was finally going to be the heroine of her imaginings, facing down the country’s most notorious killer, getting him to confess, striking a blow for women and victims everywhere. She flew down to Miami for the taping of the show with her nutrition coach, James Hester, co-author with Roni DeLuz of 21 Pounds in 21 Days. O.J. was in his trailer, with an assistant pastor from his church. According to a source in the room, as he was having makeup applied, he kept saying, “I can’t believe I’m doing this, I can’t believe I’m doing this,” over and over.

The interview took four hours. He began to cry when he started talking about the murders. She asked about the knife—he said it was true, he remembered having a knife. She asked if indeed he did forget his wallet and keys in the pants he wore at the crime scene, and he said he remembered that part for sure, too. She asked if he went to her grave, ever. “He said,” says a source, “‘I go to her grave and curse her for ruining my life.’”

At the end of the interview, he told everyone that he was a man of God, and he believed that he would see Nicole and his mother one day in heaven.

He and Regan spoke for a little while as well. Regan thought that the lines about the knife, and the wallet and keys, were tantamount to an admission of guilt of some kind, and she was incredibly proud of herself, but she kept her feelings under wraps.

“One day, I might curse you too,” he said.

Then her bubble burst. By November 13, the consensus among News Corp. executives was that they couldn’t wait any longer to announce the project, since a cameraman at the TV taping had leaked a video clip to Entertainment Tonight. There was one problem: Regan said the book wasn’t ready. It wouldn’t go into galley form for several days. The news was announced on Tuesday, November 14, even though only Regan, Mark Jackson, and the book’s editor had seen the book. The explosion was immediate, with outraged talking heads burning up the airwaves. Howard Kurtz said it was the “most appalling, shameless, exploitative thing I have heard of in the history of television, maybe the history of recorded civilization.”

But News Corp. is accustomed to outrage, and the word from on high was to stay the course. After some hand-wringing, Friedman signed off on the decision, too. She didn’t want HarperCollins to be known as a place that killed books. Also, she didn’t want to leave Regan in the limelight on something that still had the potential to be a big success—and Regan was insisting to everyone, including HarperCollins executives, that the book they had not seen was going to be a hit. “All along, Judith was telling us, ‘It’s a confession, there’s no ambiguity, there’s no reason to be worried about this project,’” says a News Corp. executive. “And we didn’t have the book, so we had to go on what she told us.”

On Thursday, Friedman addressed the company in her weekly marketing meeting. “Judith says she has done what Marcia Clark could not do,” she said. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the book.”

Someone raised a hand. “Don’t you think we should donate the profits to domestic-violence victims?”

Friedman pulled herself up. “Everyone knows how charitable I am and the company is,” she said. “But we are not planning on donating the profits of this book.”

L’Affaire O.J. had become a truly massive scandal. And here is where, for Regan, the drama accelerated ominously. Regan has always been confident of her ability to use the press to control a situation, and she began to go public with her frustrations. As it happened, though, this was just what News Corp. executives had begun to realize they needed: a villain, a scapegoat, distancing the company from the project, making it one woman’s mad dream, and allowing them to reap some of the benefits. It was decided that Regan should be allowed to say whatever she wanted, says a source close to the situation—let the lady be the lightning rod, let her take the abuse from journalists. Many have suggested that Roger Ailes was the architect of this strategy, given the fact that a lot of the heat was coming from people within the News Corp. universe, notably from Ailes protégés like Bill O’Reilly. And a lot of it, in an organization filled with loose cannons, and looser lips, was simply piling on, not rational corporate behavior at all. The tale of the O.J. book, of a powerful publisher transgressing a simple and obvious moral line for profit, was perfect for Fox’s shrill commentators—even if it did happen to be about one of their own.

Earlier in the week, Regan read a monologue on her Sirius radio program about her history of abuse and her need to see O.J. confess on behalf of all battered women everywhere (she has long declared that her ex-husband abused her). On Thursday, the transcript, which News Corp. executives had access to, was leaked to Drudge, and picked up on Friday by Col Allan of the New York Post, who’d had numerous run-ins with Regan. To many observers, the four-page screed that the Post printed was evidence that Regan had lost all sense of proportion. In fact, she never submitted it for publication. “How anyone got their hands on that transcript,” says a source at Sirius, “is the $64,000 question.” According to a source close to the situation, News Corp. put it forth as part of its media strategy. (News Corp. sources allege that Regan released the transcript to Drudge.) When Regan’s ex-husband began to defend himself against her claims of abuse in the press, Regan told the New York Post that she wanted them to run photographs of her beatings, but then never produced them.

The galleys of the book were finally ready on Friday, and distributed to a small circle of executives. They were unenthusiastic. On Saturday, Regan began to get worried, and suggested they hold If I Did It so that a letter from a forensic psychologist could be placed under the front cover. She wanted to make it clear that the book was intended to be read with the understanding that these were the ramblings of a psychopath. Everyone was getting nervous. News Corp. COO and president Peter Chernin and others brainstormed for a way to survive the media storm but not abandon the project—donate the money to domestic-violence victims or make a deal with the victims’ families, the Browns and the Goldmans. Jackson, Murdoch executive vice-president Gary Ginsberg, and News Corp. general counsel Lawrence Jacobs took a flight to Indianapolis at 7 a.m. Sunday morning, and sat down with the families. Hashing out the details, they agreed to disgorge all of their profits and then some to the Browns and the Goldmans.

By Monday morning, Jacobs, Ginsberg, and Chernin were having misgivings about the deal. The affiliates were dropping out, the media storm was continuing, and they weren’t going to get any money from this? Regan sent an e-mail saying that she, too, wanted to cancel the book—she felt the damage was done. She was surprised, though, when she talked to an executive who said that they were also canceling the TV show. She was finally going to be a heroine—why was everyone always making her the devil? “It was like James Cameron with Titanic,” says one source. “She was out there getting her ass kicked, and she wanted to prove everyone wrong, to show them her work of art.” The plug was pulled publicly. Murdoch, reached early in the morning in Australia, saw no reason to delay. Though the Browns had been agreeable to a payout of about $5 million, Nicole’s sister Denise Brown went on the Today show and told them she’d rejected News Corp.’s proposed “hush money” out of hand.

It was a disgusting circus, and Regan had been at the center of it: That was enough to convince a lot of people in the company that she was far too destructive to remain in her position. “We didn’t say, ‘Let’s wait for the next shoe to drop and can her,’ but whatever remaining goodwill she had up to O.J. was lost,” says a source close to the situation. Back in L.A., Regan was remarkably subdued, padding around the office for a couple of weeks, barefoot in her jeans and Armani blazer, drumming up business.

She didn’t count on another firestorm. But three weeks later, on December 13, another Regan book, Peter Golenbock’s 7: The Mickey Mantle Novel, an “inventive memoir” about Mantle’s life, came under attack. (Understandably. Consider: “Mickey enters her, going in nice and easy. He waits for the yelling and the screaming, waits for her to tell him how good it was, waits for an ooh or an aah, any reaction at all, but no … While he works away at it, Marilyn just lies there staring at him with cold, accusing eyes.”)

News Corp. executives began to realize they needed a villain, a scapegoat, distancing the company from the O.J. project, making it one woman’s mad dream, and allowing them to reap some of the benefits.

The media smelled blood, and the supposed sullying of Mantle’s name hit the cover of the Daily News. Friedman hit the roof. Here was Regan pulling a bait-and-switch with another one of her titles. By this point, Friedman was sick of playing nice. Regan, too, was incensed, believing colleagues were leaking negative stories about the book.

Feeling the pressure, Regan blamed the book’s editor; she hadn’t yet read it herself. News Corp. executives were appalled, as was Murdoch. “Mickey Mantle felt like another major blunder,” says one executive. “It just reinforced the sense that she’s an irresponsible editor.”

Next came the infamous call from Jackson. Earlier that week he had told her that the book was going to be “reedited.” It was up to Regan to comply, or they were killing the book. Period.

Jackson is a mensch of a guy, by all accounts—a crafty, smart lawyer who was beloved in Regan’s office, with a grudging respect for Regan herself. The way the conversation was originally reported, she’d told Jackson, “Of all people, the Jews should know about ganging up, finding common enemies and telling the big lie”—everyone was against her, specifically a Jewish cabal composed of Jackson, Friedman, editor David Hirshey, and ICM agent Esther Newberg. (“I don’t believe that the four of us have ever been in a room together at the same time, not even at Michael’s,” says Hirshey.) Lawyer Bert Fields defended Regan by explaining, “She never said ‘Jewish cabal,’ but rather that there was a cabal of people attacking her in the media,” and furthermore that she was trying to explain that “Jews particularly should understand, because of the Holocaust, what it’s like to be a victim of the ‘big lie.’”

Jackson reported the conversation to Friedman, who instantly went into action. HarperCollins lawyers decided that there was sufficient basis to dismiss her without paying the last three years of her contract. Friedman had a short conversation with Murdoch. The press release went out at seven. It was all done so quickly there was no time to catch one’s breath. Then everyone left for the News Corp. holiday party.

At the Sixth Avenue Hilton, 8,000 News Corp. employees gathered in three floors of ballrooms, each ballroom decorated to represent a continent. Australia had a lifeguard, England had shepherd’s pie, and Asia had a lot of video games, karaoke, and dim sum. (There was no Africa.) Everybody was getting BlackBerry messages about Judith Regan—the drunker employees were telling their best Regan stories, and the drunker managers were saying that it was they who were responsible for canning her, didn’t you know. Friedman told editors that she had fired Regan—when she said it, people began to clap.

Murdoch sat in the VIP section in the balcony above “Europe.” As it turns out, he didn’t know that Friedman was telling people Regan was fired—because he wasn’t even aware that she had been fired. He certainly hadn’t expected Friedman to fire her that night, before the holiday party. Although a News Corp. spokesperson denies it, some in the company are certain that Friedman misinterpreted their conversation—Murdoch had given his okay to fire her at some undetermined point in the future. But once it had been done, there was no turning back.

Stripped of her empire, Regan is now traveling between Los Angeles and New York, thinking about moving forward. She absolutely wants to go traveling, maybe to Thailand with her old friend and ReganBooks author Maura Moynihan, with whom she had dinner a few nights after the firing at L’Orange Bleue, a French Moroccan belly-dancing joint on Crosby Street. They shared a bottle of Pinot Noir. Regan had heard that people were applauding her downfall at the Christmas party, and she laughed at the idea of it. “Judith never played for low stakes,” says Moynihan. More recently, she’s been saying that she’s starting a multimedia company with TV deals in Shanghai and Bali. She also told Moynihan she was never going to publish another book again.

Fields has threatened litigation against News Corp., but it seems like the case will most likely be settled, and Regan is asking for a public apology from News Corp. stating that she is not an anti-Semite. “Allegations of anti-Semitism are maliciously false and are laughable to anyone who knows Judith,” says Stanley Arkin, one of Regan’s lawyers. (At least one member of the purported cabal, as well as another high-level Murdoch executive, maintains she’s not an anti-Semite in the usual sense.) An old friend of hers, journalist Blair Sobol, made up twenty red rubber bracelets, in an imitation of Kabbalah thread, with a stamp that reads JEWS FOR JUDITH, and gave them to Regan to give to her Jewish friends to wear. Newberg slagged Regan in the New York Times, and Regan, with great pleasure, told friends she donated $500 to a battered women’s shelter in Newberg’s name. Regan also messengered her a basket of books with a note about friendship; Newberg sent the books back. (Newberg had no comment.)

Last Tuesday, Regan was in midtown for the taping of her Sirius radio show. She sat in the corner, reviewing her notes about various guests from an orange binder through stylish translucent-framed reading glasses.

A gorgeous brunette in a striped cashmere sweater drifted into the room—it was Natalia Rose, on to talk about a book that she had published with Regan, and about living clean. “Negative emotions are something in a food context,” said Rose, her face glowing with health. “What’s happening in our head is happening in our colon.”

Judith pondered this. Later, she passed around slices of cheesecake that a guest had brought, but she didn’t have any. She had a lot of cleansing to do.

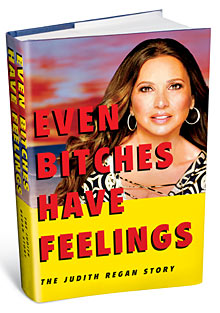

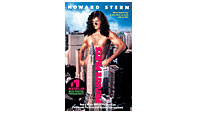

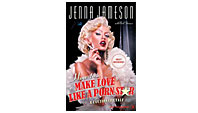

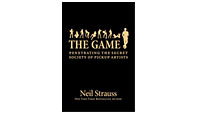

THE REGAN YEARS

Judith Regan has been a publishing auteur, building her oeuvre around themes of sex and celebrity.

Private Parts

Published: 1993

How to Make Love

Like a Porn Star

Published: 2004

The Game

Published: 2005

She’s Come Undone

Published: 1992

The Confession

Published: 2006