The least significant elements of the five new bids to develop Hudson Yards are the competing renderings on view at the MTA’s storefront on East 43rd Street. They are nearly fiction, because nobody believes any single builder will get the job.

Which goes to show how much is at stake. Together with Moynihan Station to the east, Hudson Yards is one of the largest land grabs in New York history. The idea of building a new wing of midtown atop the superblock where LIRR trains are stored and repaired has tantalized planners at least since the unsuccessful 2012 Olympics bid. And though Mayor Bloomberg also failed to move the Jets there, his zeal to get something built may be his legacy. The rezoning he secured put this giant swath of land—and 24 million square feet of new development—in play.

Right now, midtown office space is scarcer than ever. So the cash-poor MTA, which owns the yards, is looking to echo the creation of Park Avenue (which, built over the New York Central tracks, effectively created the midtown business district). The agency has turned to the private market to build the platform—and get all the added value. It’s a developers’ bonanza on the scale of Rockefeller Center, and it’s worth as much as $7 billion.

The MTA may choose one team, which in turn will carve up the 26 acres, thereby spreading risk. Or the MTA will split up the schemes itself. Either way, the bids with big tenants attached appear on much stronger ground than the others, and several of those tenants (News Corp. on Tenth Avenue, say, and Condé Nast over to the west) could well end up here.

The yards is not an isolated project. Any development there will have an impact on a planned extension of the 7 train, an expanded Javits Center, the north end of the High Line, the metamorphosis of the Farley Post Office into the much-anticipated Moynihan Station, and the adjectives applied to Bloomberg and Eliot Spitzer in the history books. Every bid includes a big residential component (one calls for 7,000 apartments) plus a school and a cultural center—the ostensible makings of a new neighborhood.

It won’t happen soon. The western half of the site requires further rezoning, meaning more opportunities to mess with (or kill) the plans. But even as battles are fought in the yard, alliances have formed to the east, where many of the same tycoons want to move trains, arenas, and towers around like Tinkertoys. Some of those men will get extremely rich. Read on to see which ones—and how.

Five rough drafts for developing 24 million square feet—and why none of them will be built.

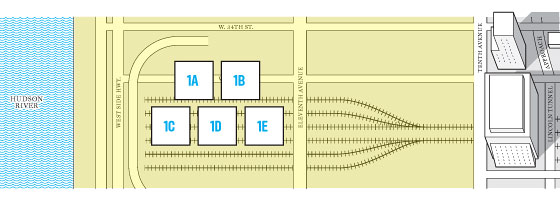

1A.EXTELL

Principal: Gary Barnett

Anchor: None

The Facts: Barnett is already famous for outbidding Bruce Ratner for Atlantic Yards (and losing) and for buying out Donald Trump’s development on Riverside South. Most of his other projects have been residential. Extell’s scheme, unique among the five, audaciously proposes to put the buildings on the ground flanking the yards and to carpet over the tracks with a park draped on a suspension bridge. Making up for all that green space: extra height and bulk. Stephen Holl’s design has received praise in architectural circles, with the Times’ Nicolai Ouroussoff calling it “the only one worth serious consideration.”

The Odds: Low. Rumored to be the least capitalized of the bunch and therefore a weak contender. Also has much less experience building at this scale.

Power Hire: Marc Shaw, Bloomberg’s first deputy mayor and former head of the MTA.

1B.BROOKFIELD

Principal: Ric Clark

Anchor: None

The Facts: Clark and Brookfield don’t get nearly as much press as Vornado’s Steve Roth and Related’s Steve Ross, but they’ve been trying for years to build a new office tower on a site they own over the train tracks just west of the Farley Post Office. A national, publicly traded company, Brookfield knows its politics: It gives a lot of money to the Democratic Senate Campaign Committee—and has the mayor’s girlfriend on its board.

The Odds: Dark horse. The plan, which has no fewer than seven major architectural firms attached, is drawing praise for good urbanism, including new streets and parks that people might actually use. But Brookfield decided to proceed without a big tenant, hoping to retain flexibility until the infrastructure is built. Not so good for winning the bid, but this smartly positions it to buy up individual pieces from the team that does.

Power Hire: Josh Sirefman, former head of the city’s Economic Development Corporation.

1C.TISHMAN SPEYER

Principals: Jerry and Rob Speyer

Anchor: Morgan Stanley

The Facts: Already owners of Rockefeller Center, the Chrysler Building, and, most recently, Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, father Jerry Speyer and son Rob want another showpiece. The presence of Rob, who together with his father assembled the $5.4 billion Stuyvesant-Cooper megadeal, at the project’s introduction suggests that Jerry is nudging his heir further into the spotlight. The firm describes its bid as a combination of Rockefeller Center and Berlin’s Sony Center, which is one of those redevelopment projects better suited to tourists than to Berliners.

The Odds: Modest. Morgan Stanley, the bid’s anchor tenant, is itching to move, but the prospect of a high-security financial office tower may prove less appealing to the MTA than that of a media corridor. The bulky, blocky buildings are unlikely to win over anyone on the aesthetics, though the town-green “forum” area is a nice touch.

Power Hire: Tony Mannarino, former No. 2 at the EDC.

1D.DURST-VORNADO

Principals: Douglas Durst and Steve Roth

Anchor: Condé Nast

The Facts: Durst owns 8.3 million square feet in midtown, with a portfolio mostly on Third and Sixth Avenues in the Forties. Grandfather Joseph built the business, and father Seymour spent three decades gradually assembling the parcel that is now becoming One Bryant Park (financed by post-9/11 Liberty Bonds). Known for environmentally sound development, son Douglas includes far more than the “greenwashing” that most developers toss into projects to collect tax credits; the bid is packed with new technology for water recycling and co-generation. Durst has partnered with Vornado’s Steve Roth, who owns the lion’s share of the property around Penn Station (see following pages).

The Odds: Hard to say, but intriguing. Positioned well to grab at least a large piece of the pie. Designed by Pelli Clarke Pelli and FxFowle, the bid has as anchor tenant Condé Nast, which, according to Si Newhouse, has, incredibly, already outgrown its 1999 Times Square tower. Even if one of the other plans (say, Related’s) is adopted, the Condé Nast building has a good chance of going up.

Power Hire: Jordan Barowitz, one of Bloomberg’s press handlers during the mayor’s first term.

1E.THE RELATED COMPANIES

Principal: Steve Ross

Anchor: News Corp.

The Facts: Related owns over $10 billion in property even without Hudson Yards. Its biggest and most visible New York project is the Time Warner Center, but Related is all over town: from the Gwathmey tower at Astor Place to the former Bronx Terminal Market. And Related is known for partnering with more conservative name-brand architects, like David Childs of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

The Odds: The plan is the front-runner—though it will almost certainly be rejiggered to incorporate aspects of the other bids. With Kohn Pederson Fox as lead architect, its strength lies in having lined up News Corp. and established a financing partnership with Goldman Sachs as well as Ross’s chummy relationship with city planning czar Dan Doctoroff (they both once owned pieces of the Islanders).

Power Hire: Vishaan Chakrabarti, who was a wunderkind at SOM, then ran the Manhattan Office of City Planning during the rezoning of the West Side, and probably knows better than anyone how this redevelopment will work.

Renderings: From top, courtesy of Extell Development Company; courtesy of Brookfield Properties; courtesy of Tishman Speyer Properties; Dbox/courtesy of Related Companies; courtesy of Durst-Vornado

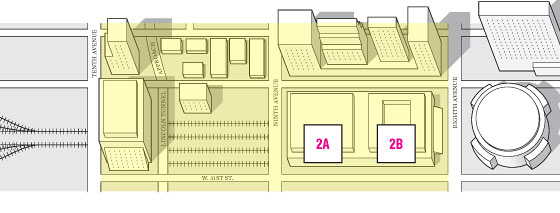

How a new Madison Square Garden, a new Penn Station, and a new shopping mall could be squeezed into the Farley Post Office.

The whole West Side plan began with Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s notion that the old Farley Post Office would make a splendid gateway to New York. By righting the wrong of Penn Station’s 1963 demolition, it gave aesthetes and civic boosters a reason to fall in behind a big rebuilding project. Only later did it become a potential gold mine for developers.

With the backing of Governor Spitzer, and driven by the developers Steve Roth of Vornado and Steve Ross of Related, the plan has swelled to include a replacement for the seedy Madison Square Garden, which ought to make owners Charles and James Dolan very happy. Yet they may be the ones to scotch the plan.

Why? The colonnade facing Eighth Avenue, topped by the neither-snow-nor-rain-nor-heat-nor-gloom-of-night motto, will be the project’s public face. Everyone wants a piece of it. The current plan calls for the Farley to be split in two, with the train station in the eastern end (where the portico is) and the new Garden being stuffed in the back, with a glass shell in between.

But here’s the catch: The Dolans have to agree to move, or nobody gets a big payoff. And, not wanting their arena to be stuck out of view, the Dolans are holding out for a portion of the Eighth Avenue portico as their entrance, with major signage. They also want a glass wall inside the complex, abutting the train station, so passersby can see the action. The point of Moynihan’s plan was that Penn Station craves dignity, and an entrance to the circus isn’t what he had in mind. In essence, the Dolans are holding the senator’s vision hostage. You want a station here? You have to come through us.

The second but no less crucial player in all this is Related/Vornado. Competitors at Hudson Yards, they’ve teamed up here to take advantage of the Dolans’ departure. Their plan to replace the Garden calls for a second, modern entrance to Moynihan Station across the street from the Farley, a retail development above that, and a mix of office towers on all Vornado’s nearby turf. (For that story, turn the page.) The tracks and related infrastructure stay more or less where they are, beneath the current and future stations, and newly accessible from both sides of Eighth Avenue.

2A.THE NEW GARDEN

Principals: Jim and Chuck Dolan

Developer: ESDC

Its grim aesthetics aside, the current Penn Station runs at twice its intended passenger capacity and must be replaced. But it’s been slow going. Various railway-station designs have been commissioned by the Empire State Development Corporation over the past fifteen years—and in each iteration, the architectural flair of the glass roof has been pared down. This March, the ESDC finally purchased the Farley building from the Postal Service for $230 million, and Maura Moynihan, the senator’s daughter, has turned her boundless energy to the task of keeping alive her father’s dream, putting her voice behind anybody who can move the project forward. As she declared at the press conference last Wednesday: “Whatever we have to do to get the jackhammers moving, we’ll do it.”

2B.MOYNIHAN STATION WEST

Visionary: Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Developer: ESDC

Its grim aesthetics aside, the current Penn Station runs at twice its intended passenger capacity and must be replaced. But it’s been slow going. Various railway-station designs have been commissioned by the Empire State Development Corporation over the past fifteen years—and in each iteration, the architectural flair of the glass roof has been pared down. This March, the ESDC finally purchased the Farley building from the Postal Service for $230 million, and Maura Moynihan, the senator’s daughter, has turned her boundless energy to the task of keeping alive her father’s dream, putting her voice behind anybody who can move the project forward. As she declared at the press conference last Wednesday: “Whatever we have to do to get the jackhammers moving, we’ll do it.”

But the project may not be as straightforward as the senator thought it would be. It’s become apparent that the Beaux-Arts building isn’t exactly lined up above many of the commuter tracks, leading to the plan for a second entrance across Eighth Avenue.

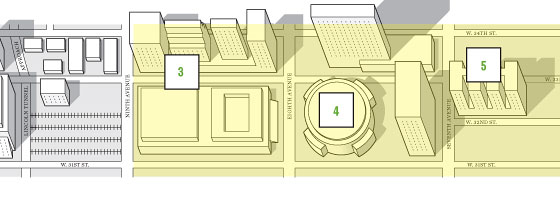

With the old Garden all but demolished, two builders propose a new station and a major high-rise upzoning.

If Steve Roth succeeds in purchasing the current Madison Square Garden site in partnership with Steve Ross, his play will go down in history as one of New York’s great real-estate coups. Why? As of this July, the answer was simple, if audacious: They would tear down the structure and redevelop the site as an eastern entrance to Moynihan Station, adding two 90-story towers rivaling the Empire State Building in size. Ross was to take charge of this development—the nearby Time Warner Center was a similarly complicated site and proved a financial success—and he hired the same architect (SOM) to design the complex, this time together with Norman Foster.

But the Roth-Ross plan immediately encountered problems. The architects reportedly clashed (no surprise, given the demands of the site and the egos involved); Spitzer’s team and civic organizations like the Regional Plan Association, while in theory supportive of Moynihan Station, expressed misgivings over a scheme to once again bury a train station under massive development (see the nightmare of today’s Penn Station); and the developers themselves reportedly got cold feet. So the two-iconic-towers plan has been scratched, and instead, the developers are lobbying the city to let them redistribute the buildings’ bulk, piecemeal, all over the neighborhood.

3.MOYNIHAN STATION EAST

Principals: Steve Ross and Steve Roth

Potential Roadblock: The Dolans

Even without the pair of planned skyscrapers on top, Moynihan Station East will still sit beneath a glorified shopping mall. (The two halves of the station will, together, contain 1 million square feet of retail space, three times as much as can be found at the Time Warner Center.) Total project cost for the stations is estimated at about $2 billion, of which Vornado and Related have offered to put up only $450 million. It’s expected the state will squeeze more out of them, but the remaining funding would come from the city, the state, and the Feds. But will this part of the complex take Moynihan’s name? Amtrak wants to stay on this side of the avenue, and stick with “Penn Station”—a link to its own history.

4.THE MOYNIHAN STATION DISTRICT

Principals: Steve Ross and Steve Roth

Potential Roadblock: City Planning

Under the Related-Vornado proposal, the city would rezone the immediate neighborhood to accommodate 4 million to 5 million square feet of development rights—in effect, chopping up the two hypothetical towers and sprinkling them into smaller parcels from Ninth Avenue almost all the way over to Fifth. Conveniently for Roth, Vornado has spent the last decade acquiring about a dozen sites within the zone. He and Related would develop the sites (mostly as office buildings) in a 50-50 joint venture.

5.HOTEL PENNSYLVANIA

Principal: Steve Roth

Potential Roadblock: Sheldon Silver

It was only about a month ago that Vornado announced plans to build a new headquarters here for Merrill Lynch, but already the plans are in doubt. Despite a ruckus by a few preservationists, it’s hard to see what about the building is worthy of preserving, aside from its famous phone number (Pennsylvania 6-5000). Still, that’s the least of the problems: Merrill’s new CEO, John Thain, may not support the move to midtown; the rezoning might not move through in time, given that Merrill’s current lease runs out in 2013; and Sheldon Silver will put pressure on Merrill to stay downtown. If Merrill walks away, the KPF-designed building across Seventh Avenue would also be in jeopardy.

SEE ALSO

• Spitzer vs. Silver vs. Bloomberg

• Potential Nightmare Scenarios