For once, Hank Morris wasn’t wearing a crewneck sweater. The shapeless garment had become the Democratic political consultant’s uniform, no matter the season or occasion, whether at an Election Night victory party or at the funeral of a close friend. One day in 2004, however, Morris was in the gym. He spotted a longtime acquaintance, the hedge-fund manager Orin Kramer, whom he knew from Kramer’s years of big-money fund-raising and donating to Democratic candidates. Kramer also oversees pension-fund investments for the State of New Jersey, and at the time he was battling to create the most stringent regulations in the country for the Garden State’s retirement money. Kramer had focused on restricting the ability of investment managers to contribute money to politicians. Morris scoffed.

“Those rules are really stupid,” he told Kramer. “Under your rules, which are the most restrictive in the country, I could actually still be doing business and they wouldn’t apply to me, because I never wrote a political check.”

Kramer walked away thinking that Morris was, unfortunately, probably correct; no one could ever construct a perfectly corruptionproof regulation. He had no idea why Morris, long one of New York’s premier political strategists, cared about the arcana of state pension-fund regulations.

The next time Kramer saw Morris wearing something other than a crewneck sweater was March 2009. Suddenly, the gym conversation made awful sense. Morris was in a dark suit and a white dress shirt. His hands were cuffed behind his back. He had just been indicted on 123 counts of shaking down investment firms that wanted a piece of New York State’s $150 billion pension fund.

“I realized years ago that I didn’t know how to write rules that included someone’s closest fraternity brothers or members of his fishing party,” Kramer says sadly. “It also didn’t occur to me to say the rules would apply to the political consultant to any major officeholder.”

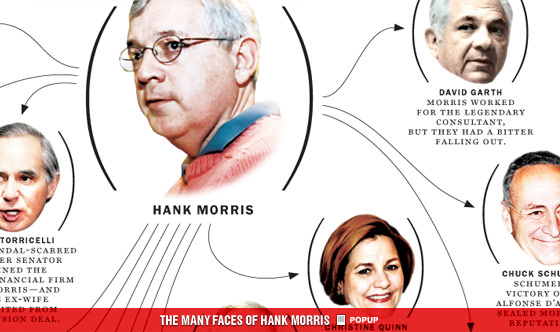

Hank Morris was big. He had a hand in most major New York Democratic political campaigns, and many others around the country, for nearly 25 years. He gave the state and the world Senator Chuck Schumer. His clients and protégés, from Christine Quinn to Josh Isay, are plentiful in the upper ranks of New York politics. That’s part of the reason Morris’s indictment and arrest have had such far-reaching ripples. His story is full of characters who don’t just cross paths but whose grudges and debts and favors double and triple back. Feuds begun in obscure intramural party maneuvers find their echo in federal court more than 30 years later. “This thing is like Madoff,” says one politically connected New York financier. “It touches everyone we know.”

But the sheer number of friends and acquaintances involved is only one reason why, to New York’s political class, Morris’s fall has felt like a death in the family. Calling the saga Shakespearean is a reach, but it is a tale of not just money and power but also fathers and sons and morality. Morris, 55, has pleaded not guilty, and some of his friends see him as the victim of a politically motivated attorney general, Andrew Cuomo, who is generating headlines by criminalizing a commonly accepted practice. “This is the way business was done,” a Morris friend says. “Not just here.”

Yet Morris’s choice to capitalize, on a grand scale, on his intimacy with former State Comptroller Alan Hevesi and the state pension fund is ethically dubious, at best. “Look, when you’re a consultant at Hank’s level, all kinds of opportunities come to you,” a political rival says. “People want things from you. And you’ve gotta say yes or no.” The shock Morris’s friends and enemies have experienced over the past months is often coupled with another reaction: empathy. They too live in a world where trust is currency, the ability to bend the truth and navigate gray areas an art form, and rationalization a survival skill. Did one of their tribe, enamored of his own cleverness, cross the line?

He grew up in Westbury, Long Island, the middle-class son of a business executive at ABC-TV and a community-college librarian. In 1974, as a 21-year-old Columbia student with a taste for politics, Morris worked for Denis Dillon, the underdog Democratic candidate for Nassau County district attorney. Morris talked so well that he was soon running the campaign—and Dillon’s upset win over the Republican incumbent launched Morris’s reputation as a wunderkind strategist.

There was something besides Morris’s youth that made him distinctive in that era. “When we were younger, there was an idealism to our political activism,” says a Long Island Democrat who grew up with Morris. “Being involved was important; working in politics wasn’t. I remember Hank, in 1977, calling several of us to offer us jobs on the David Peirez campaign for Nassau County executive. I said to him, ‘What’s going on?’ He said, ‘I can get you great money for this!’ With Hank, there was always that preoccupation with money. It wasn’t evil. It was just this fixation.”

Morris went to Columbia Law and then to work for another son of Long Island, David Garth, one of the brilliant pioneers of modern political strategy and one of the first consultants to become a famous name. Garth became a legend by getting electoral victories for senators (Heinz, Specter), governors (Carey, Byrne, Grasso), and mayors (Lindsay, Koch) and also because of his irascible personality. Morris joined Garth’s shop at about the same time as another young, mercurial political junkie, Phil Friedman. It proved a volatile, short-lived mix, with Friedman and Morris leaving to set up their own shop, after working with Garth on Jay Rockefeller’s winning campaign for West Virginia governor in 1980. The split set off an angry feud, with Garth saying he’d fired Morris over what he claimed was a missing payment.

Friedman and Morris were wildly different personalities: Friedman flamboyant, Morris socially awkward. Friedman bought a 55-acre Westchester estate from Pamela Harriman; Morris lived in a cramped two-bedroom on the Upper West Side. Beyond politics, however, they also shared a fascination with playing the stock market. “Their desks faced each other, and when one of their stockbrokers would call, they’d run away from each other so they wouldn’t know what the other one was doing,” one colleague remembers.

“Hank was always watching TV business channels,” says Bill Cunningham, who worked in an office with Morris and Friedman in the late eighties and in 2001 helped craft the surprise mayoral win of Michael Bloomberg. “If anyone is suggesting that after Hank elected Hevesi comptroller he got interested in business rather than politics, I would suggest he was very little interested in politics going back to before 1990. Hank sat on the board of some sugar company, and at one point he was trying to figure out how to engineer a takeover with other board members.”

The firm had some wins and some expensive losses, like John Dyson’s 1986 bid for one of New York’s U.S. Senate slots, but a turning point for the partnership was the 1987 stock-market crash. Friedman lost a large amount of money; Morris didn’t. The firm dissolved, but when Friedman grew seriously ill, Morris, among others, generously tried to help. Friedman’s decline ended sadly in 2005, when he committed suicide. At the funeral, political consultant George Arzt was struck by Morris’s behavior. “Hank was wearing one of his sweaters,” Arzt remembers. “He shook my hand and said, ‘Thank you for coming.’ I said, ‘Hank, Phil was a friend. Why wouldn’t I come?’ He shook his head like he normally did. I thought, ‘What an odd remark.’ ” Morris was in mourning. But Friedman’s penniless demise seems to have made him more determined never to end up the same way.

The two men were digging through Dianne Feinstein’s attic. Hank Morris, along with his new business partner, Bill Carrick, was trying to figure out how to turn San Francisco’s former mayor into the next governor of California. They’d come to Feinstein’s home to sift through the souvenirs of her political career. One of them popped a videotape into a VCR. They were stunned by what they saw: a tearful yet resolute Feinstein announcing the shooting deaths of City Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone.

Morris and Carrick turned the footage into in a classic TV spot (the clip showed up last year in Milk) that established the theme of Feinstein’s 1990 run: “tough and caring.” She lost, to Pete Wilson, but she was well-positioned for a winning U.S. Senate campaign in 1992, also run by Morris and Carrick.

Morris’s distinguishing talent as a political consultant was for identifying and relentlessly focusing on a pivotal issue in a campaign. “He’d spend a lot of time figuring out exactly the angle he wanted to take and run the campaign almost in a Napoleonic fashion, pointing all of the guns at one part of the line, blowing open a hole, and then charging through,” Cunningham says. “Hank was always trying to figure out, ‘Where’s that one point in the line?’ ”

In a business overrun with slick self-promoters, Morris was the polar opposite: zhlubby, generally allergic to the camera, with a grandfatherly head of white hair. Gruffly intelligent and quirky—Morris’s phone greeting usually consisted of “So. So. So. So”—he demanded complete control of a campaign. “Hank would do the direct mail, he would do the media, he would do the buying,” says Hank Sheinkopf, a strategist for Liz Holtzman and Mark Green in races against Morris and his client Hevesi. “All the cash flowed to him.”

Morris met Chuck Schumer in Albany, when the relentless Brooklyn pol was a state assemblyman. In 1998, they teamed up to topple Republican senator Al D’Amato. Morris’s battering ram was the slogan “Too many lies for too long,” perfectly highlighting D’Amato’s ethical lapses. Morris also made sure every reporter in the state heard about D’Amato’s referring to Schumer as a “putzhead.”

“I thought Hank was brilliant,” says Howard Wolfson, the communication director for Schumer’s ’98 campaign. “Also incredibly frugal. Hank’s offices were unimpressive. His campaigns were always run leanly. Making sure every dollar went into communications, as opposed to other things, was very important to him.”

Instead of following the conventional path after that career-making upset, however, and trying to make a president, Morris retreated. He was growing bored with politics. “The hard part of the political-consulting business,” a friend says, “is that every other November, you work yourself out of a job. Then you pick up your pots and pans and start pitching business. Hank grew up in an environment where he never had to do any of running around pitching business.”

And he didn’t want to start. Morris held on to a few clients—Schumer, for whom he handled an easy 2004 reelection bid, and another old pal from the State Assembly days, Alan Hevesi. “Hank had a very limited clientele—like Tom Hagen in The Godfather,” Cunningham says. “He stayed with people he’d known for a long time, but he wasn’t looking for the next candidate for governor or senator. He was busy with his investments, and it made sense: You do a campaign once in a while for a guy you know, you get paid something for that, and you have this other life.”

Morris’s first real foray away from politics seemed benign. In the mid-nineties, he bought Curran & Connors, a Long Island company that published corporate annual reports. His contacts brought in business. Bear Stearns chief Jimmy Cayne ordered his staff to dump its previous printer and hire Morris’s company, apparently in hopes of cozying up to Morris’s client Hevesi, who was then city comptroller. “I like Hank,” Arzt says. “But I was very wary after that incident with Garth. Hank was pushing the printing business, and he would always say, ‘Look, George, do you have any corporate clients you can send my way?’ ” But Morris soon found a more lucrative method of leveraging his friendships.

Andrew Stein is an unlikely source of inspiration. His career in electoral politics ended with an extravagant, abortive 1993 run for mayor that was helmed by Phil Friedman. Stein’s marriage fell apart not long afterward. But he quickly built a new career. “Andrew is a strange guy,” a longtime political acquaintance says. “But he knows all these rich people, and they swear by him as a deal-maker.” Stein made introductions, put in a well-placed word for clients, and extracted large fees for knowing the right people.

One of those relationships was with fellow Democrat Carl McCall. Stein was an adviser during McCall’s successful 1998 campaign for state comptroller. While McCall was in office, Stein became a placement agent—a kind of middleman—for investment companies seeking money from the state-pension fund, of which the state comptroller is the sole trustee. In 2001, McCall tried to move up the ladder and ran for governor. When the campaign stumbled, Stein reportedly tried to nudge aside McCall’s chief consultant, David Axelrod, and have him replaced with another friend, Hank Morris. Axelrod quit, but Morris instead chose to run the campaign of the Democrat who wanted to succeed McCall: Alan Hevesi.

Hevesi was a young Democratic assemblyman representing Forest Hills when he met Morris. Through bruising losses (in 1989, to Liz Holtzman, for city comptroller) and even rougher wins (a victorious 1993 rematch with Holtzman, in which Hevesi assailed Holtzman over alleged ethical violations involving a bank loan), the two men became not so much strategist and client as brothers in arms. That bond was most severely tested in 2001, when Hevesi ran for mayor. His campaign is remembered in political circles for two disastrous strategic choices by Morris. First came the consultant’s too-clever-by-half campaign theme: MEBQ. Placards and ads carried those baffling four letters in large type, and size didn’t help clarify the idea that Hevesi was supposedly the Most Experienced, Best Qualified candidate. Worse was Morris’s bizarre attack on the head of the city campaign-finance board. He’d shown a penchant for deeply strange behavior before: In 1992, Morris ran a futile congressional campaign with his 68-year-old mother, a retired librarian, as the candidate. Six years later, after Schumer’s election to the Senate, Morris went on NY1 and described his strategy by deploying a set of toy bears.

This time, Morris’s twisted logic was that he was a mere volunteer on the Hevesi campaign, so he didn’t need to bill for his services, thereby freeing up money for the candidate to spend elsewhere. The campaign-finance board was dubious, and in a public hearing, Morris railed at its chairman, the Reverend Joseph O’Hare. “We all told Hank not to do it,” says one of his closest friends. “But he believed he was right and he was going to prove it, no matter what.” After the board voted to punish the campaign by withholding matching funds, Hevesi agreed to pay Morris, but the episode generated terrible publicity for his struggling candidate. Hevesi finished a distant fourth in the Democratic primary behind Freddy Ferrer, Mark Green, and Peter Vallone.

One year later, Hevesi rebounded, easily winning the Democratic nomination for state comptroller with Morris calling the shots, then eking out a victory over Republican John Faso in the acrimonious general election. Hevesi hammered Faso over his conservative positions on gun control and abortion—Morris-identified vulnerabilities, but issues the state comptroller has little to do with.

It was Morris’s last big campaign. In 2003, he passed the tests required to become a securities broker or dealer. He also took care of another requirement for the financial business, becoming affiliated with Searle & Co., a small Connecticut securities firm that had its offices above a Christian Scientist reading room in Greenwich, Connecticut, and whose clients were mostly wealthy local families. With his best friend taking control of a $100 billion pension fund, Morris would launch the firm into an entirely new orbit.

The universe of investment options is very, very large. The time and research abilities of the staff of a public pension fund are very limited. So someone in the middle of that equation who can get an investment firm a meeting with the public officials controlling the money—and who can vouch for the worthiness of the beseeching money manager—is a very valuable person indeed.

“Cuomo has made the term ‘placement agent’ the equivalent of ‘child molester,’ ” says one investment-banking veteran. “But the use of placement agents is widespread and in many ways they’re necessary. And 99.9 percent of these guys sit at a desk all day and have no political contacts.”

“There are many smaller firms that are not going to get in the door without a placement agent,” an experienced public-pension-fund player says. “If you have a legitimate placement agent that does serious due diligence on a money manager before they bring them in, that’s somebody who the professional staff trust, because they can’t see everybody. But then there’s the agents who are politically connected; that’s how they get in the door. In New York, there is a high degree of the politically connected.”

When an associate tried to sever the deal, Morris passed word: “Tell that little peanut of a man that I can take the business away as easily as I provided it.”

As of Hevesi’s election, no one was better connected than Morris. Investigators say he helped force out Jacques Jiha, the chief investment officer for the state’s Common Retirement Fund, when Jiha didn’t pay enough attention to the equity-fund managers recommended by Morris and Jack Chartier, Hevesi’s chief of staff. Morris, investigators say, helped select Jiha’s replacement, then-33-year-old David Loglisci, a former investment banker. One large mystery in the case is what, if anything, Loglisci got out of his dealings with Morris. Prosecutors have not charged Loglisci with profiting directly from the arrangement. The prestige of his powerful job, where he oversaw the flow of investments from the country’s second-largest public fund, seems to have been Loglisci’s greatest reward. But his job also appears to have paid off for his friends and family.

Investigators allege that Morris inserted himself into existing relationships between the pension fund and money managers. One example they cite is the comptroller’s history with the Carlyle Group. The global private-equity behemoth is used to getting its way. With $84 billion under its management, and advisers and investors who’ve ranged from former president George H.W. Bush to George Soros, Carlyle knows how to exert muscle and push buttons. But for years Carlyle was frustrated in its attempts to land New York State pension money using its in-house sales staff. So it enlisted an outside placement agent: Andrew Stein. And in 2002, Stein earned about $4 million in fees, getting Carlyle money from the state pension fund, overseen by then-Comptroller McCall, as well as the city pension fund, administered by then-Comptroller Hevesi and a board of trustees.

Hevesi succeeded McCall in January 2003, and for a while Stein continued to thrive. In April 2003, the state comptroller’s office agreed to invest in a new European fund assembled by the Carlyle Group. Stein’s Arapaho Partners collected a $1.7 million brokers fee on the deal. But it was Stein’s last big score from the pension fund. “Knowing Hank,” a longtime political colleague says, “he thought, Well, I could do this too.”

For the next two years, when Carlyle wanted New York State investments, it went through Morris, landing $730 million in pension money. Searle collected $13 million in fees, investigators say, and passed more than $7 million of it to Morris.

Sometimes Morris drummed up new business on his own. In 2004, investigators say, Morris contacted Odyssey Investment Partners. One of the firm’s founders, Stephen Berger, had long been active in Democratic politics. Odyssey had hired CSFB, the large investment bank, to serve as its placement agent with the state pension fund—until Morris allegedly told Berger that the fund had its “own” placement agent, Searle. Odyssey switched to Searle and soon received $20 million from the state pension fund.

The direct approach worked fine, but Morris extended his reach in a multitude of creative ways. Through the Carlyle deals, investigators say, Morris came into contact with Barrett Wissman, a family friend of David Loglisci’s and a hedge-fund manager based in Dallas. Wissman brought a raft of his own connections, and in April, pleaded guilty to paying Morris hidden fees in exchange for facilitating state-pension-fund investments. Morris pushed westward into California’s pension system in 2005 and 2006, through Wetherly Capital, a firm run by longtime Democratic fund-raiser Daniel Weinstein. Morris’s political-strategy firm had worked for Los Angeles mayor James Hahn’s 2005 reelection bid and Phil Angelides’s campaign for governor in 2006; Weinstein was a prominent moneyman for both. Weinstein hasn’t been charged, but in March a former Wetherly employee, Julio Ramirez Jr., pleaded guilty to secretly sharing placement-agent fees with Morris.

Ramirez connected Morris with Aldus Equity, a Texas firm that worked as a consultant to New Mexico’s state pension fund. Aldus eventually received $375 million in New York pension money, with Morris collecting a fee; Aldus also recommended New Mexico deals that netted fees for Morris as well as Daniel Hevesi, the older son of New York’s comptroller. Morris, Cuomo says, wasn’t above using strong-arm tactics to keep the money rolling in. When Saul Meyer, Aldus’s principal, tried to sever the arrangement in 2006, the attorney general says that Morris passed word: “Tell that little peanut of a man that I can take the business away as easily as I provided it.”

But as Morris’s business multiplied, so did the number of people who wanted to wet their beaks. A complex—and often comic—network of payments of questionable legality often ensued: Former New Jersey senator Robert Torricelli just happened to become affiliated with Searle, with his ex-wife receiving part of an $800,000 placement-agent fee when the pension fund delivered a $40 million investment. An affiliate of the Quadrangle Group, an investment firm founded by Democratic insider Steven Rattner and the keeper of Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s personal fortune, was suddenly helping to distribute a low-budget movie called Chooch, produced by David Loglisci’s brother, as Quadrangle sought (and received) a $100 million investment from the state pension fund.

Chooch is the scandal’s artistic low point. (“Hank made me go to a screening,” a Morris friend says. “It was the worst movie ever. Ever.”) Its most poignant chapter involves Ray Harding, the longtime head of New York’s Liberal Party. In a political wit’s famous phrase, the Liberal Party was neither liberal nor a party: Harding was its only meaningful member, and he bartered the party’s valuable ballot line and endorsement for patronage jobs. Harding lost control of the party in the eighties during a bitter fight with Mario and Andrew Cuomo; he eventually made peace with the governor and his son and returned to power. In 2002, however, the Libs lost their state-ballot line when their candidate for governor abruptly pulled out of the race. That candidate? Andrew Cuomo.

Harding’s family fell on hard times. His son, Russell, had been president of the city’s Housing Development Corporation during Rudy Giuliani’s second term as mayor (coincidentally, Morris’s printing company had an HDC contract while Russell Harding was in charge). In 2005, however, the younger Harding went to prison after pleading guilty to embezzlement and child-pornography charges. Ray was struggling to pay the legal bills. Morris got Harding into the placement-agent game, and Harding allegedly collected $800,000 in fees. “If Ray Harding took $8,000, would anyone give a shit?” a New York political strategist says. “No. The biggest mistake was probably that they all took too much.”

Harding, Loglisci, and Morris—through their lawyers—vigorously deny they’ve done anything illegal. They’ve pleaded not guilty to all charges. “Hank Morris is innocent,” his attorney says, “and we will defeat these charges at trial.”

The most damaging sideshow, at least for Morris, may turn out to be a romance gone wrong. Peggy Lipton played the hippie-chick cop on the late-sixties TV show The Mod Squad. At the start of this decade, she and Andrew Stein were a frequent “Page Six” item. But in 2004, not long after Stein was frozen out of the comptroller’s office, Lipton took up with Jack Chartier, Hevesi’s longtime deputy—who happened to be married. Nevertheless, in 2004 Chartier was commandeering state cars and drivers to have Lipton shuttled to doctor appointments where she was treated for cancer, as well as less noble destinations like nail salons and grocery stores. Markstone Capital, a California-based investment firm that was chasing $250 million in New York pension money, allegedly tossed $100,000 to Lipton in order to curry favor with Chartier and Morris.

Chartier’s limo adventures were exposed in 2006, when Hevesi got into his own chauffeur scandal. Hevesi’s use of state cars to transport his ailing wife seemed like a big deal at the time, because it led to Hevesi pleading guilty to fraud and resigning from the comptroller’s office in December 2006. But Chartier’s problems, and the spurned Stein, would eventually come back to haunt Morris. Chartier and Stein haven’t been charged in the scandal. Possibly because they’ve also been talking to investigators.

Morris’s defenders argue that he filed all the paperwork required in his business dealings and that trading on your friendships is hardly illegal. “Maybe, for the civic good, we’d rather not see our political system work this way, and our comptroller’s office work this way, and politically connected people make money through their political connections,” a Morris associate says. “But that doesn’t make it criminal.” A public official who had known Morris for decades puts it more colorfully: “I mean, people send chocolates all the time. What Hank did smells, but a lot of stuff in Albany smells.” Shouldn’t the politically savvy Rattner and Berger, whose images suggest they’re above this sort of thing, have known better? A New York Democrat who has also been a financial-industry player shrugs. “You do what you need to do to get the business,” he says.

Some of Morris’s longtime friends are saddened and disbelieving that the man they know could be a criminal mastermind. “Hank is clearly not somebody who would take ethical risks,” one of his political partners says. “In the campaign context, he’d often be somebody who’d caution people, ‘Don’t do that; it’s just not worth the risk.’ ”

The case, if it ever makes it to court, will turn on whether Morris was selling an ability to open doors—or an ability to keep doors locked. He can make a pretty good argument for having functioned as a traditional lobbyist or broker in many of the deals; other episodes, where the SEC and Cuomo allege that Morris had to be paid in order for the comptroller to do business with a money manager, may be more problematic. One example: The comptroller’s office, according to the SEC’s complaint, had a prior relationship with a Memphis firm called CSG. In 2005 CSG approached Loglisci about managing some of the pension plan’s hedge-fund investments and was told the discussion couldn’t move forward unless Morris was hired. After CSG signed up with Searle, the firm received $765 million in New York pension money; Morris pocketed about $1 million in fees as a result, investigators claim. CSG disputes the narrative. “Loglisci told the firm that Hevesi was the final decision maker when it came to selecting asset managers for the [fund], and Loglisci said that Morris … might be helpful on the subject,” a spokeswoman says. “CSG was never told that it ‘had’ to hire Morris or to pay him a fee if CSG wanted the [state’s] business … Paying fees to placement agents … has been standard practice in the public pension-fund industry, and was appropriate so long as those fees were disclosed to the fund, as they were in this case… CSG was aware of nothing that indicated that Morris, Hevesi, and Loglisci were engaged in any conduct that was illegal or improper in any way.”

So far Cuomo has racked up popularity points and headlines for pursuing corruption, and he’s brought badly needed reforms to the pension-fund system. But he has yet to charge or settle with some of the best-connected players, including Rattner. After more than two years of investigation, the attorney general and the SEC still haven’t clarified what role, if any, Alan Hevesi played in the scandal, and there’s still no hint of a trial date. Is Cuomo, as he gets closer to a 2010 run for governor, willing to push the probe into more uncomfortable territory?

Morris hasn’t spoken publicly since 2001. That was the tumultuous year Hevesi was trounced in the mayor’s race and Morris fought with the campaign-finance board; he also got married and bought a $4.1 million house in East Hampton. He’s been mostly holed up there with his wife, an attorney turned New Age minister, poring over law books in hopes of assisting his attorney, Bill Schwartz, a Columbia Law School classmate way back when. “When this first started happening, Hank went into an avoidance mentality,” a friend says. “He stopped reading the newspapers.” There’s a pause. “I worry about Hank now. If he will harm himself. He’s not made for this.”

Another close friend says his sympathy for Morris is outweighed by a different emotion: disgust. Whether or not Morris is legally guilty, he abused a lifetime of relationships. Why? “This wasn’t about Hank being greedy. It was about him trying to outsmart everyone again.” The friend sighs. “Well, he didn’t.”