“It’s impossible to tell you what I’m going to do except to say that I expect to make the best movie ever made,” Stanley Kubrick wrote to an associate in October 1971. Wily chess master that he was, the director rarely resorted to bombast. But in his third attempt to make Napoleon—a film that, according to his widow, Christiane Kubrick, “swallowed [him] up” like no other—he was willing to make an exception.

The director was on a mission. He was unimpressed by every Napoleon movie ever made, from Abel Gance’s 1927 silent to Marlon Brando’s mumbly Désirée. Kubrick—who by the time of his death in 1999 had assembled one of the world’s largest archives of Napoleon-related material—hoped to offer the most comprehensive vision of the emperor’s life, covering 50 years in three hours. And he had been trying to do that since 1967.

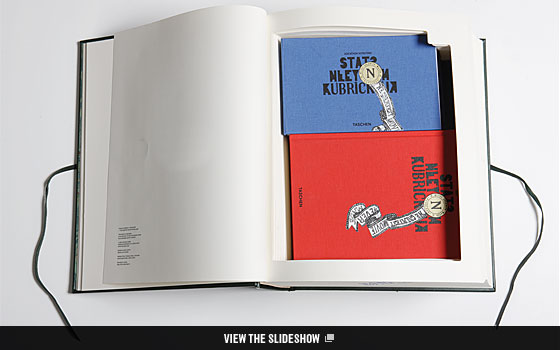

That obsession is laid out in staggering grandeur in Taschen’s new 23-pound tome Stanley Kubrick’s Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made—a book as epic (indeed, it nearly is a coffee table) as Kubrick’s stillborn film, with a price ($700) to match. You have to see it to believe it, which is appropriate when you consider Kubrick’s obsession. “Stanley was besotted with this story,” says Jan Harlan, Kubrick’s brother-in-law and producer during the latter part of his career. “He was a political beast and fascinated with human folly and vanity. Napoleon was the perfect study object for that.”

MGM had started preproduction on the film in 1967. At that time, Kubrick was the breakout genius behind Lolita and Dr. Strangelove, with 2001: A Space Odyssey just about to be released. The proposed budget? Reportedly, a cocky $5.2 million (equal to about $33 million today; in modern Hollywood, though, the film would undoubtedly cost well into nine figures). Kubrick had his eye on David Hemmings for Napoleon, with Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Jean-Paul Belmondo, and Charlotte Rampling in supporting roles. But after sinking $420,000 into the project (costumes; location scouting in Italy, France, and Romania; arranging to borrow the Romanian army to stage battle scenes), MGM backed out in 1969, after financial issues and a change in leadership (some things never change). United Artists took it on for a bit, then bailed out. Dino De Laurentiis’s Waterloo stole some of Kubrick’s thunder, then bombed, and that was that.

The book—edited by Taschen’s Alison Castle (who also put together 2005’s The Stanley Kubrick Archives)—offers a tantalizing glimpse into what might have been. The immense shell opens to reveal six smaller books, each with a different theme (costumes, locations, production) plus three small notebook-style volumes. There’s also a reproduction of Kubrick’s screenplay, the first he’s known to have written on his own. “It’s a very good script,” says Castle, “but also frustrating because he had to gloss over a lot of things. He put a huge amount of emphasis on the love story with Josephine.” Given how sexually charged their relationship is in Kubrick’s screenplay (Napoleon meets Josephine at—shades of Eyes Wide Shut—an orgy), it’s hard to picture Audrey Hepburn, the director’s choice to play her, in the role. (Hepburn turned him down.)

Harlan contends that the script was “a reader,” not a final draft, and that it would have been rewritten daily during rehearsals. “Stanley was not a great writer,” says Harlan. “He had no false pride in this area and hired writers to help him.” Perhaps, then, a central question would have been resolved. “Reading the screenplay, it is impossible to tell whether Kubrick likes Napoleon or loathes him,” says Jean Tulard, France’s leading Napoleonic historian, who contributed the essay “Napoleon in Film” to the collection. Several Kubrick biographers have written of how closely the New York–born director identified with his subject, including Full Metal Jacket co-screenwriter Michael Herr, who noted the defining traits they share: Both were largely self-educated outsiders who beat the system on their own terms, and both shared an aversion to so-called polite society. How tempting to imagine Kubrick’s empathizing with this passage from Napoleon’s memoirs: “It is very difficult because the ways of those with whom I live, and probably always shall, are as different from mine as moonlight from sunlight.”

And yet, more illuminating is Kubrick’s disaffection. Harlan believes Kubrick was torn between deep admiration and disappointment. He struggled to understand how such a capable man could be so manipulated by the philandering Josephine, or have so hopelessly miscalculated the Russian campaign that defeated him. “When Stanley was young, he played chess for money for a while in New York,” says Christiane. “[He believed] Napoleon might have learned to control himself better had he played chess. Stanley thought if you are too emotional, you lose.”

Kubrick’s Napoleon may not be dead yet. MGM still owns the rights, and Steven Spielberg and Ang Lee have reportedly talked it over. Kubrick eventually came to believe that his Napoleon would be more suited to a miniseries (conveniently, there is a 72-page suggested treatment in the Taschen book). But it could be that the project has found its perfect home as the most grandiose book ever made.

All MGM development materials, inclusive of script and treatment, © 1968 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studio Inc. and used with permission of MGM. Book materials courtesy of Taschen.

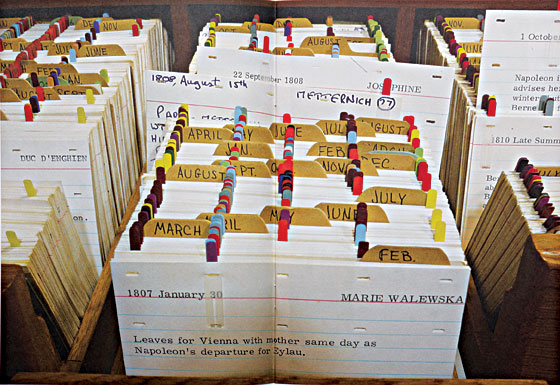

Research

Kubrick kept his script and treatment drafts in a steamer trunk and hired grad students to compile a fastidious chronology of the historical figures’ lives.

Photo: © 1978 The Stanley Kubrick 1981 Trust, provided by and reproduced with kind permission of the copyright owner.

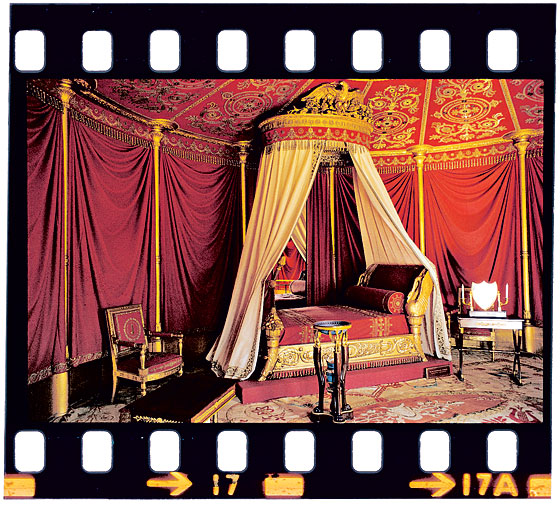

Location Scouting

Empress Josephine’s bedroom in the Château de Malmaison, seen in one of the 15,000 or so scouting photos from 1968 and 1969.

Photo: © 1978 The Stanley Kubrick 1981 Trust, provided by and reproduced with kind permission of the copyright owner.

Location Scouting

Empress Josephine’s Château de Malmaison, seen in one of the 15,000 or so scouting photos from 1968 and 1969.

Photo: © 1978 The Stanley Kubrick 1981 Trust, provided by and reproduced with kind permission of the copyright owner.

The Casting Wish List

Clockwise from top left, Jean-Paul Belmondo; David Hemmings (whom Kubrick wanted to play Napoleon); Alec Guinness; Peter O’Toole; Charlotte Rampling; Audrey Hepburn.

Photos: RDA/Archive Photos/Getty Images (Belmondo); Popperfoto/Getty Images (Hemmings, O’Toole); MGM Studios/Archive Photos/Getty Images (Guinness); Terry Fincher/Express/Getty Images (Rampling); Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images (Hepburn)

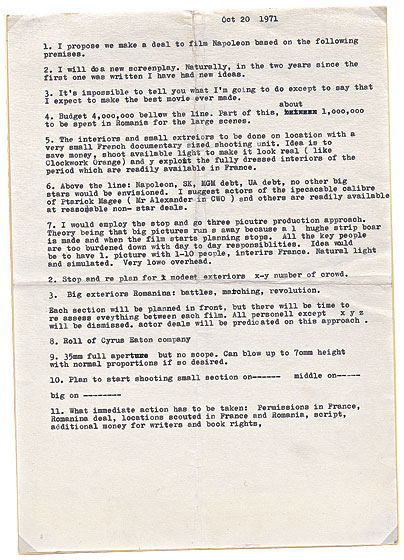

Notes and Correspondence

Kubrick floated a plan (to an unnamed colleague) for restarting Napoleon after he completed A Clockwork Orange.

Photo: © 1978 The Stanley Kubrick 1981 Trust, provided by and reproduced with kind permission of the copyright owner.

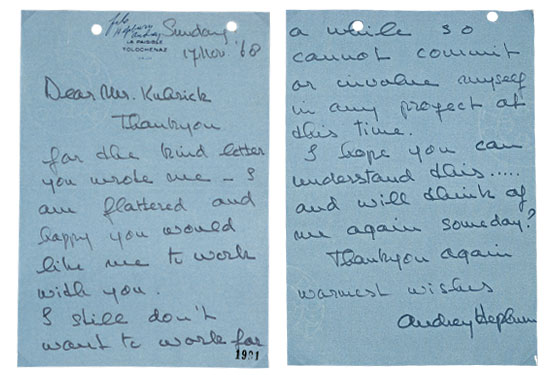

Notes and Correspondence

Audrey Hepburn graciously declined the role of Josephine.

Photo: © 1978 The Stanley Kubrick 1981 Trust, provided by and reproduced with kind permission of the copyright owner.

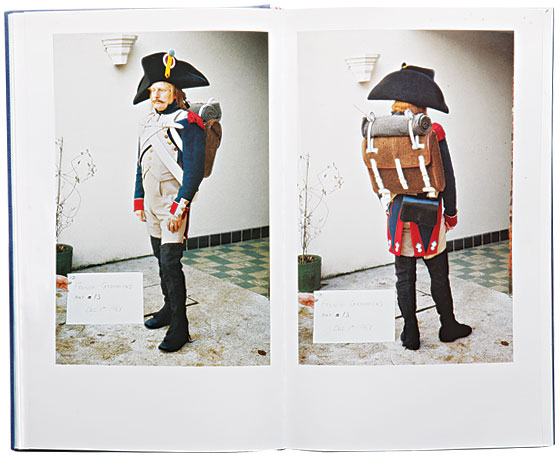

Costume Tests

Dozens of European military uniforms were camera-tested.

Photo: © 1978 The Stanley Kubrick 1981 Trust, provided by and reproduced with kind permission of the copyright owner.

Carl Henry Nacht (left) West Side Highway and 38th Street. After dinner on June 22, 2006, Nacht, a doctor who often cycled to make house calls to his elderly patients, was hit by an NYPD tow truck crossing the Hudson River Park bikeway. Shamar Porter Linden Boulevard near Williams Avenue, East New York. On August 5, 2006, Porter’s Little League team won its playoff game. He was struck by a minivan after leaving the field.