Looking out over the hulking Javits Convention Center and the mostly fallow streets that surround it from the the roof of 450 West 33rd Street, Deputy Mayor Dan Doctoroff could barely contain his enthusiasm. Sixteen stories high, the rooftop—actually a basketball court built by the once-hot dot-com DoubleClick when it occupied the space—was the perfect vantage point to showcase his vision. At the start of a sultry evening recently, he spoke with passion and certainty about the city’s future.

“What we have with the West Side is not simply an opportunity for development,” said Doctoroff, 45. “It is an opportunity to turn the area into one of New York’s great places, a place that’s a worthy successor to Rockefeller Center and Lincoln Center.”

Doctoroff warmed to his sales pitch. “We are in a golden age now in the city,” he said. “We’re at the right point in the economic cycle, and there is a spirit, post-9/11, that I don’t think we’ve ever seen before. This has opened up great opportunities.”

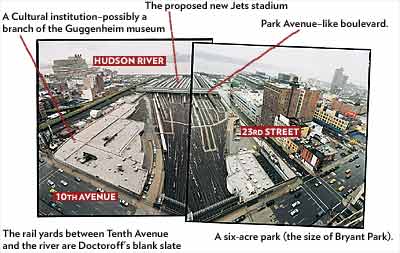

Then Doctoroff pointed to a huge rectangular hole in the ground that stretched from Tenth Avenue to the West Side Highway and from 30th to 33rd streets. The hole, of course, is the Hudson rail yards, over which a new stadium for the Jets would be built, the most visible—and contentious—part of a plan he’s been working on for a decade.

In Doctoroff’s vision, the far West Side would become, with the stadium as its anchor, a thriving center of culture, sports, tourism, and entertainment. There would be cafés, restaurants, shops, a 1,500-room hotel, office and residential space, and a ribbon of parks along the waterfront. Doctoroff’s dream also includes a broad boulevard with a center esplanade nearly twice as wide as Park Avenue’s. This boulevard would be carved out between Tenth and Eleventh avenues, and run from 33rd Street up to 42nd Street.

On the east side of Eleventh Avenue, between 30th and 33rd streets, the other open section of rail yards would be covered by a six-acre park. On its southern edge, there is space for a cultural institution—perhaps a branch of the Guggenheim museum, whose director, Thomas Krens, has expressed interest.

The noun used most often to describe Doctoroff, sometimes unkindly, is zealot. It is a pretty accurate label. The first time I met him, we had dinner at Aix. He talked for more than three hours about the city’s economic future, the far West Side, and the 2012 Olympics with such alacrity and spirit that I remember thinking when I left that he was like an Evangelical—a true believer whose endless enthusiasm comes from being convinced he is helping other people see the truth.

His plan for rebuilding New York is so complex, it seems like the kind of thing you’d come up with in an urban-planning workshop—“If you could redesign any part of the city with no constraints, what would you do?”—rather than a real, working blueprint. Even Doctoroff himself says that “nothing’s ever been done that’s this big.”

The overall vision is based on an idea he had back in 1994 to bring the Olympics to New York. But the plan now has a momentum of its own. Whether New York is the host city in 2012 or not—and the current betting is that it’s not likely—the West Side stadium has become the critical piece of his redevelopment strategy, the wheel around which everything else turns.

Doctoroff’s ambitious, almost fantasylike vision—and the arcane financing mechanisms he’s put together to get it done—have made comparisons of the deputy mayor to Robert Moses irresistible for many people. But Doctoroff quickly rejects them, in part because with Moses the vision was inextricably connected to the strong-arm. “The thing that makes any comparison irrelevant,” he says, “is that we live in a very different world. And it’s partly because of him. There’s clearly an opportunity to transform the physical landscape now, but in every case, it has to be the result of substantial community input, if not consensus.”

One of Moses’s chief gifts was his talent for circumventing any kind of legislative or political review. He created novel ways to fund projects, like Doctoroff has done, that enabled him to operate with virtual impunity. As Doctoroff used the rooftop view to lay out his plan for this neighborhood currently filled with garages and warehouse space, he didn’t seem to notice the dark bank of clouds that had been steadily sliding in from New Jersey.

“This is Manhattan’s last great frontier,” he said. “There won’t ever be another opportunity like it again.”

Then, on cue, it started to pour.

Why a stadium on the West Side of Manhattan? Why should a prosperous sports team get $600 million of city and state money? Why not build, say, a giant park? Or a new neighborhood à la Battery Park City? What should Manhattan’s last frontier become? And who should pay for it?

These are fair questions, ones that are, increasingly, at the center of the city’s debate over its future as Doctoroff pushes his program forward. His opponents agree with him at least about what’s at stake. “It is a huge opportunity,” says City Councilwoman Christine Quinn, who represents the neighborhood. “And whatever we build, that’s it. We’re not going to do it again. I just don’t think there’s been the kind of process where anyone’s tried to determine what the city really needs. The planning was done after the goal had already been decided.”

Doctoroff himself has become a flash point. While his admirers are legion, his detractors find him arrogant and short-tempered. “He’s become the de facto head of planning for the city,” says a good-government type. “And we’re thrilled with most of the stuff the city is doing in the outer boroughs and along the waterfront. It’s forward-thinking, and they’re completely open to community input. This is true on everything except the West Side. I don’t know if it’s a phallic thing with Doctoroff or what, but there is simply no discussion on the stadium.”

Fueled by the Dolans, the father-son team that owns Cablevision and Madison Square Garden, the battle for public opinion on the stadium—which includes competing TV ad campaigns, noisy press conferences, and posturing by the usual assortment of neighborhood groups—is in danger of resembling the circus that plants its tent in the Garden, a few blocks from the would-be Jets stadium.

The Dolans’ vitriol about the stadium is not entirely comprehensible. A 75,000-seat stadium would not likely draw much business from the Garden, though there would be some competition. (One interesting note in the backstory: When Robert Wood “Woody” Johnson IV bought the Jets four and a half years ago for $635 million, one of the people he outbid was Charles Dolan.)

The Dolans’ ad says the $600 million the city would have to invest in the stadium could be used to rebuild schools, put a computer in every classroom, or open firehouses. “So here’s the choice,” the ad says. “Invest $600 million in neighborhoods, or spend it on a West Side stadium for the Jets.” (As it happens, in the ten years the Dolans have owned the Garden, they have paid no real-estate taxes—essentially an $80 million subsidy.)

The ad has ignited an air war, with the Jets launching their own TV salvo this week, pointing out the Dolans’ less-than-pure motives. But the Dolans are far from the stadium’s only opponents. Peter Solomon, who was a deputy mayor in the early Koch years and who gave Doctoroff his first job after law school, at Lehman Brothers, might be expected to support it. Instead, he’s on the fence. “I’m not at all sure it’s a good idea,” says Solomon. “Support for the stadium is really thin, and I told Dan he has to make the case why this is the only solution. Why the Jets won’t move elsewhere.”

Doctoroff doesn’t have his own ad campaign—yet—but this is his case: There are six critical pieces to the West Side development: the stadium, the Javits Center expansion, the platform over the eastern section of the rail yards, rezoning to allow for greater density, parks and open space, and the extension of the No. 7 train. Remove any one of these elements, which Doctoroff argues work together and feed off one another, and it would be like pulling a piston out of an engine. Everything grinds to a halt.

His argument for the stadium is fairly simple: It literally fills a void. The rail yards form an enormous, gaping hole that has to be filled with something. Otherwise, it will be impossible to attract any private-sector money (not to mention people) to the area. In fact, there are two holes. The one where the stadium will be built is between Eleventh Avenue and the highway and runs from 30th Street to 33rd. The other, often referred to as the eastern rail yards, and the one Doctoroff envisions as a six-acre park, is between Tenth and Eleventh avenues.

In Doctoroff’s admittedly controversial analysis, the stadium, which will be a multipurpose facility that serves as an adjunct to the Javits Center, is a no-brainer. “This is clearly the best use of the space. We are talking about a building that will be in use every day of the year,” Doctoroff says. “We will fill the area with activity. There’ll be conventions and shows and theaters and parks. The building alone will have five restaurants and 40,000 square feet of retail space. Ask the Guggenheim if they’d have any interest in going there if what would be next to them is empty space.”

One of the most common arguments against the stadium is that football is played too infrequently. But Doctoroff says the building will be used for more than just Jets games. He even steadfastly refuses to refer to it as a stadium and chastises those who do. “It is the New York Sports and Convention Center,” he snaps—in spite of the fact that the Jets will own the building.

“The idea is to fill it with life all year round. That’s what will bring investment to the area,” Doctoroff says. “If you took the stadium out of the plan, the neighborhood would remain dormant for a very long time.”

Inspiration for the plan comes partly from the construction of Grand Central Terminal, which was built on a platform over the open rail yards on what is now Park Avenue. The new properties created on both sides of the avenue were sold to pay for the construction and developed as hotels and office space.

A phalanx of towers is one thing. A stadium is quite another. “Stadiums are dead zones,” says Brian Hatch, a former deputy mayor of Salt Lake City who was involved in that city’s Olympic effort and is now a galvanizing force for opposition to the stadium. “It’s feast or famine with these facilities. There’s either no one there or there are tens of thousands of people flooding the area.”

“Is this the best project?” asks Gargano. “I haven’t seen anything better. The city gets its stadium, we get the Javits, and $800 million in private investment is hard to pass up.”

Hatch, who moved to New York four years ago and is a consultant on municipal issues, had a kind of unofficial advisory role on the New York Olympic effort (he’d talk to Doctoroff once a month) until he decided to oppose the stadium. “There’s no first-class neighborhood anywhere that’s anchored by a stadium.”

Four and a half years ago, Rudy Giuliani very publicly invited the Jets to move to a new stadium on the West Side in his State of the City speech. It was January, and Woody Johnson, the great-grandson of one of the founders of Johnson & Johnson, had just bought the team. Everyone knew the Harley-riding, philanthropic Republican fund-raiser from New Jersey had paid a lot of money for the team and would have to find additional sources of revenue—like a new stadium—to make his investment work. (The team’s lease at the Meadowlands is up in 2008.)

At the same time, Doctoroff was moving ahead with his Olympic proposal, which had identified the West Side as the place to put a stadium, one that would have to have a purpose when the Olympics moved away. He had seen the Jets’ sales memo prepared by Goldman Sachs; the Jets’ needs and his matched perfectly.

But, of course, there’s another party to the deal: the public. The total cost of the stadium is $1.4 billion. The Jets have committed $800 million to the project; the city and state will have to split the remaining $600 million. For their investment, the Jets get ownership of the building and all of the responsibilities and rewards that come with it. They will also insure the city and state against construction-cost overruns and sign a 49-year land lease with the state.

“Giving a $600 million subsidy to a sports team in a time of fiscal crisis, when the city and state have serious infrastructure needs, is beyond outrageous,” says Dan Golub, spokesman for Assemblyman Richard Gottfried, one of the project’s leading opponents.

Many say the Jets are getting a sweetheart deal. Everyone knows municipalities all over the country have been hoodwinked over and over again into spending precious public funds to make already-rich owners of sports teams even richer. It’s a given that owners as a group have replaced (not undeservedly) the mustache-twirling, mortgage-foreclosing banker as the cartoon villain everyone loves to hate.

But Doctoroff argues that the Jets are hardly getting a free ride. The $600 million public investment covers $375 million to build a platform over the rail yards and $225 million for a retractable roof. In order to build anything over the rail yards, they have to be covered with a platform. By this logic, the $375 million is not a gift but a necessary expense to turn the rail yards into a developable site.

The argument for the retractable roof is more complex: The Jets want to play in an open-air facility; the roof is what makes the stadium a multiuse building. The bill for this is $225 million—so, by this argument, $225 million of public money is being used to attract $800 million of private investment.

Doctoroff says that those who claim the Jets are getting a $600 million handout are engaged in “superficial thinking.” He sees the stadium as a revenue generator, a business venture rather than a gift. “The building itself will be a significant contributor to city and state coffers,” he says. The city will issue bonds to pay for most of its share. “The annual debt service on the bonds will be $42 million over 30 years. In its first year of operation, the building will produce $72 million in tax revenue,” Doctoroff says. “So there will actually be a net cash flow. We’re using taxpayer revenue to generate taxpayer revenue. What we’ve tried to do is make the minimum public investment to get the maximum private-sector response.”

Ten years ago, a friend invited Doctoroff to the semifinal game of the World Cup between Italy and Bulgaria at Giants Stadium. It was a hot July afternoon, and Doctoroff, who had never been to a soccer game, had very low expectations. “I’d been to the Super Bowl, the NBA finals, the World Series, and only a month before I’d seen the Rangers win the Stanley Cup,” Doctoroff says. “But that soccer game turned out to be the most exciting event I’d ever seen.”

Predictably, the stands were filled with screaming fans, fueled not simply by the usual team allegiance but by national passion. “I was thinking the amazing thing about the New York area is, you could play that game with almost any two countries in the world and you’d generate the same excitement,” he says. “And I started wondering how it was that the world’s most international city had never hosted the Olympics, the world’s most international event.”

Doctoroff, then an investment banker, left the stadium with the vague notion that New York ought to stage the Olympics, and over the next year and a half, it became a personal obsession. He began, completely on his own, researching whether it was a good idea. He didn’t tell anyone except his wife what he was doing.

“I’m normally a very rational person,” he says. “I’d made my living making very rational decisions.” But this took on a life of its own. The more time he spent on it, the more enthralled he became. “It was an idea I thought was so logical and so powerful from so many different perspectives.”

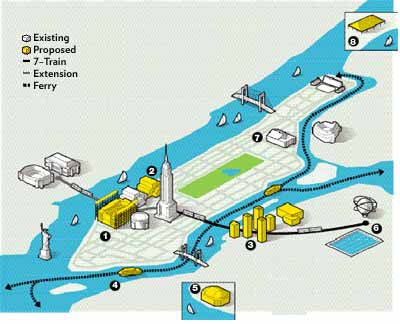

The overarching concept for staging the Games in New York is called the Olympic X. Every venue is along one of two intersecting transportation axes. The north-south axis follows the waterfront from Staten Island all the way to the tip of northern Manhattan. The east-west axis follows the commuter-rail lines from the Meadowlands under the Hudson River to 33rd Street, and out to Flushing Meadows. The intersection of the X is where the Olympic village will be, which is on the Queens waterfront across from the U.N. From the Olympic Village, athletes would use ferries going north and south and dedicated trains to get to their events. It’s an elegant reimagining of New York’s relationship to its waterways.

Doctoroff met Michael Bloomberg four years ago when he put the touch on Bloomberg for his Olympic bid, and Doctoroff was hired as deputy mayor for economic development shortly after the election. The two Masters of the Universe immediately knew they were in sync on New York’s economic future.

“The thing I also came to understand,” Doctoroff says, “is the catalytic effect the Olympics can have. They occur on a deadline. Nothing else in government happens this way, and that’s why everything drags on so long.” Doctoroff says the impact of the Olympic effort can already be seen in the way the West Side project is progressing. In the next few weeks, the 6,000-page environmental-impact statement will be completed. “There’s no way that could’ve happened without the deadline. And our goal is to have the shovels in the ground on the stadium and the extension of the No. 7 train by the time the International Olympic Committee makes its decision next year in July.”

“There’s massive exposure for the city here and no legislative review,” says Ravitch. “People are worried, but no one wants to be accused of killing the Olympics.”

Now, Doctoroff believes, the main thing that stands in the way of beginning the stadium in the next year is litigation of some kind.

And yet, there is little likelihood at this point that the Olympics will come to New York. Among other things, the stadium may be more impediment than draw. The IOC doesn’t like controversy, and it’s currently looking for bid plans that are simpler and less expensive. So if you throw the Olympics out of the equation, why not just build the thing in Queens and be done with it?

The Jets have emphatically said they won’t go to Queens, but few people believe that. “If you were being offered four waterfront blocks in the middle of Manhattan, would you be talking about your backup plan?” asks Golub.

West Side residents argue that a Queens location for the stadium would enable the rail yards site to be used, as has been proposed by the Hell’s Kitchen–Hudson Yards Alliance, solely for an expansion of the convention center that could be covered with a park.

According to Doctoroff, Queens is not nearly as attractive as it seems. “You’ve got to remove everyone around Willets Point, and there are a few environmental issues as well,” he says. “To remediate that site would cost around $230 million. Then, you’d have to drive piles into the marshland to support the structure, and this would cost over $100 million.”

the one issue on which almost everyone is in agreement is the need to expand the Javits Center, which is too small, and doesn’t have enough meeting rooms or space where several thousand people can sit down and listen to a speaker, watch a film, or view a presentation. The stadium would add all of these options to the convention center plus an additional 200,000 square feet of floor space. Charles Gargano, the state’s economic czar, says this means the Javits Center would be able to book at least 38 additional shows a year, which translates into a minimum of 120 days of activity.

“The goal for the state is now and has always been to expand the Javits Center,” says Gargano. “We told the city we will not spend taxpayer money to build a stadium, but we would help with the infrastructure. And that’s what we’re doing. Is this the best project for that space? I haven’t seen anything better. The city gets its stadium for the Olympics, we get the Javits expansion, and $800 million in private investment is pretty hard to pass up.”

Jay Cross, president of the Jets—suddenly a convention-business expert—says there is a need in the marketplace for a facility to handle 200,000-square-foot shows, which are the bread and butter of the industry. “We’ve talked to the biggest people in the business—Reed Exhibitions, G. Little, VNU, and the Jewelry Show—and they can’t wait to do business with us,” he says.

The stadium’s opponents contend that, whatever arguments the Jets make now, once the stadium is built, they will have little incentive to use the building as an extension of the Javits Center, since convention business is far from lucrative—most convention centers around the country are subsidized in some way. “If the choice is booking convention business, which loses money,” says Hatch, “or booking Springsteen, it’s pretty clear what they’ll do.”

Cross, who played a key role in the construction of the American Airlines Arena in Miami and the Air Canada Centre in Toronto, argues that there are only a handful of events every year that can fill a 75,000-seat stadium anyway. He says they will compete for events like the Super Bowl, the Final Four, and college bowl games. As far as concerts go, he says that business is overrated.“If you look at the Meadowlands, they do maybe two concerts in a good year. Five in an extraordinary year,” he says. “Most acts play arenas in the winter and amphitheaters in the summer.”

Still, the Jets are not quite in sync with the city and state on how their agreement governing use of the facility will work. Both Doctoroff and Gargano say the Jets will be mandated to use the building for convention-style events a significant number of days a year. Cross has a different idea: “We’ll let the market determine what works in terms of use of the building.”

Even if you disregard all of the other arguments against building a stadium on the West Side, you are still left with one critical question. As one opponent put it to me, “How can you put a 75,000-seat stadium in one of the most congested parts of the most developed borough in the biggest city in the world?”

The Jets, of course, have an answer. They did a survey of their season-ticket holders, who on average have had their seats for ten years, and 70 percent said they would use public transportation if the games were on the West Side.

Critics believe this number is wildly inflated, and they cite a Madison Square Garden study that found that only 40 percent of the people attending games at the Garden on weekends used public transportation. And that building sits right on top of Penn Station and seven subway lines.Cross counters that the Garden study is old and it suits them to put those numbers out because of the Dolans’ position opposing the West Side stadium. Even so, he argues, if 70 percent of the fans take public transportation, that would still mean 7,000 cars. If only 50 percent leave their vehicles at home, that would mean 11,000 cars coming into Manhattan on Sunday afternoon—a fraction of the weekday numbers.

“Life is about trade-offs,” one insider says. “And the trade-off here is pretty clear. The city and state get to use someone else’s $800 million, and for that, there’ll be traffic and congestion for an hour before the games and an hour and a half after the games, eight or ten times a year on a Sunday afternoon.”

The process by which the stadium is going forward, while somewhat more democratic than that employed by Robert Moses, stops short of being entirely transparent. The stadium will be built on state-owned land controlled by the MTA, highly circumscribing any role for the City Council.

The MTA and the city will have to reach an agreement on the value of the air and development rights over the rail yards. The MTA will essentially sell these rights to the city. This is no small issue. Some experts say these rights could be worth as much as a billion dollars over 25 years. It is money the MTA desperately needs, and any deal that appears to shortchange the authority could spark a huge public outcry.

Total costs for the rest of the project, which includes a second platform over the eastern rail yards and nearly $2 billion for the No. 7 train extension, could exceed $4 billion. For this, Doctoroff has come up with a clever financing instrument that enables him to bypass most legislative review. Bonds will be issued through a newly created authority called the Hudson Yards Infrastructure Corporation, and about $1 billion of the debt will be backed by another government body, the Transitional Finance Authority.

The TFA was created by Giuliani to enable the city to issue more debt than is constitutionally permitted. It has been used by mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg during times of financial crisis.Here, the council does have some control. The area has to be rezoned to allow for Doctoroff’s planned high-rise office development. Without the development, there’s no revenue generated to pay back the bonds. “Using the TFA as a credit enhancer is very clever,” says former MTA chairman Richard Ravitch. “It circumvents the capital-budget process. Dan would say it will all get repaid, but I’m not so confident. I think this funding is very risky.”

Ravitch says he has refrained from commenting on such issues, because he hated being second-guessed when he was in government. But he believes this issue is so important he had to speak out. “I think there’s a massive exposure for the city here and no appropriate legislative review. People are worried, but no one wants to be accused of killing the Olympics.”

If the projections are wrong, taxpayers would be left holding the bag; the city’s ability to borrow money could be affected for years. Doctoroff says it’s a risk worth taking. “We’ve got three of the leading investment banks in the area of public financing onboard,” he says, “and we’ve made the numbers available. There are six sources of repayment, and it’s all been modeled out in great detail.”

Ravitch is not convinced. He says that if the stadium is being built for the Olympics, then why not wait until next July to see if New York is selected before putting shovels in the ground?“What’s the rush?” he asks rhetorically. “The rush is because the Jets want construction to begin before the IOC decision. And if we’re doing this for the Jets and not the Olympics, we should say that so politicians can feel free to voice opposition without worrying that they’re hurting the city’s Olympic chances.”

Still, says Doctoroff: “If the Olympics were not in the picture, there’s not a single thing in the West Side plan I would change.”

Doctoroff is still optimistic about New York’s chances in the Olympic lottery. “I know the competition is fierce among the five cities,” he says. “But I wouldn’t have kept at this for the last ten years if I didn’t think we have a very good shot.”

There are those who believe that, in the end, even if New York doesn’t get the Games, the effort will still have lasting significance. “Dan’s major contribution is telling the story of New York as the world’s second home and how we have successfully created a diverse but united community,” says NYU president John Sexton, a member of the NYC2012 planning committee. “And he’s thinking about how we make the city a better place 25 or 50 years from now.”

Of course, Doctoroff himself already has one foot in that new city. He believes his own rhetoric, and he argues his case with the passion of a new convert. Possibly, he’s more salesman than builder, more Professor Harold Hill in The Music Man than Robert Moses in The Power Broker. But in this environment, to get anything built requires that simpleminded fervor. “At the end of your life,” he says, “you want to be able to look back and feel like you made a difference.”

Dan Doctoroff’s new New York

This (see picture at top) is roughly the plan Doctoroff had for theOlympics—but who needs the Olympics? Ariver-centric city is a pretty inviting vision for NewYork, no matter what the IOC decides.

1. The West Side stadium could mean more thanjust a home for the Jets. Beneath it could lurk asuper-transit-terminal, offering a connection betweenthe 7 subway line, the LIRR, and a westward-extendedMetro-North.

2. Stadium or not, the Javits Center problemmust be solved. Otherwise, world-class conventiondollars might abandon Manhattan forever.

3. An expanded version of Queens West couldbecome the East River’s version of Battery ParkCity.

4. New York could become the new Venice with anetwork of East River ferries.

5. Coney Island’s resurgence couldcontinue with a Chelsea Piers–esque sportsplex.

6. An environmental cleanup could bring aregatta with six boathouses to lakes in FlushingMeadows–Corona Park.

7. Harlem’s 369th Regiment Armory couldbe renovated, bringing sports and major eventsnorthward.

8. Pelham Bay Park could be rehabilitated toinclude the popular beach destination’s firstindoor pool.