Toni Morrison never liked that old seventies slogan “Black is beautiful.” It was superficial, simplistic, palliative—everything her blinkered detractors called Morrison’s complex novels when the 1993 Nobel Prize transformed her into a spokeswoman and a target. No better were those blinkered admirers who invited themselves to touch her signature gray dreadlocks at signings, as though they harbored some kind of mystical power.

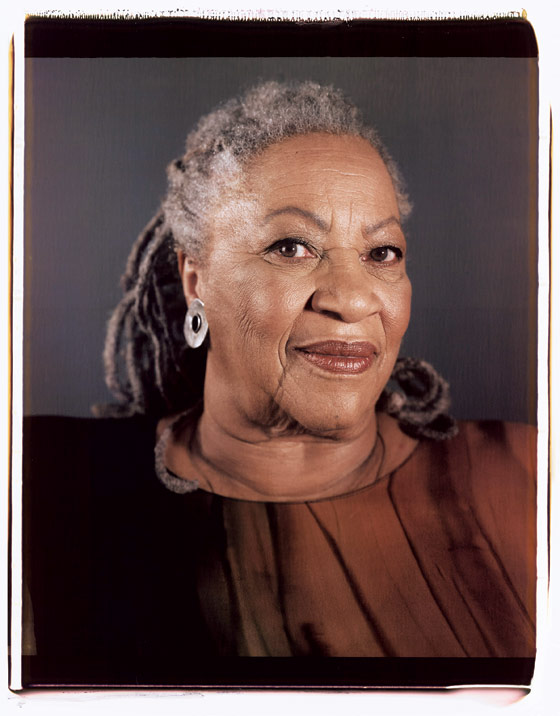

Still, even at 81, sporting both a new novel and a new hip, Morrison is as grand as she’s ever been. When we meet in her many-gabled house in the aptly named village of Grand View-on-Hudson, about 25 miles north of Manhattan, that bountiful woolen hair matches the lower half of a soft, enveloping sweater. Her face is polished in places and fissured in others, like the weathered stone of Mount Rushmore: the first black woman Nobelist, who’s lived long enough to speak to the first black president. Born only two years after Martin Luther King Jr., she’s a great-grandmother of assimilation—and she looks the part.

Morrison’s voice is as layered and visceral as her writing. The author growls, purrs, giggles, and barks. Discussing politics, her voice rises in indignation before cresting and breaking into a loud chuckle. (“They should have that in the military, or the prisons—a little affirmative action! Let’s bring some white guys in!”) She surrenders to a wheezing, shoulder-shaking, freight-train laugh when describing a particularly gruesome Funny or Die video. She booms theatrically in recounting the ghost stories her parents would tell every night. (“Sharpen my knife, sharpen my knife, gonna cut my wife’s head off!”)She slows to a pedagogical rhythm while discussing her “invisible ink”—symbols and allusions in her work that would be picked up only by a deep reader, or maybe someone writing a dissertation twenty years from now. And in more confessional moments, Morrison reverts to a register that’s gotten stronger with age, a husky but girlish whisper imparting both vulnerability and authority. That’s how she broaches, gingerly, the death of her son Slade, sixteen months ago, at 45, “which has clouded everything, everything, everything, everything,” she says. “It’ll be with me like a shroud, or a cape, forever.”

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Wofford, and still thinks of that as her real name. She picked up the nickname “Toni” in school (from her saint’s name, Anthony), and Morrison was the last name of her long-ago ex-husband. To this day, she deeply regrets leaving that now world-famous name on her first novel, The Bluest Eye, in 1970.

“Wasn’t that stupid?” she says. “I feel ruined!” Here she is, fount of indelible names (Sula, Beloved, Pilate, Milkman, First Corinthians, and the star of her new novel, the Korean War veteran Frank Money), and she can’t own hers. “Oh God! It sounds like some teenager—what is that?” She wheeze-laughs, theatrically sucks her teeth. “But Chloe.” She grows expansive. “That’s a Greek name. People who call me Chloe are the people who know me best,” she says. “Chloe writes the books.” Toni Morrison does the tours, the interviews, the “legacy and all of that.” Which she does easily enough, but at a distance, a drama-club alumna embodying a persona—and knowing all the while that it isn’t really her. “I still can’t get to the Toni Morrison place yet.”

That might be because Chloe knows Toni doesn’t belong to her. The things that made her Toni Morrison—Nobel laureate, political litmus test, college staple, gray-haired eminence—have never been completely in her control. Which isn’t to say that she didn’t break seemingly impenetrable barriers. As a student, then an editor, then an author and academic, Morrison fought unapologetically for the importance of considering racial politics in literature and of bringing marginalized American forces and shameful American secrets into the cultural mainstream. No one benefited more from her bold stance on the barricades of inclusiveness than Morrison herself.

And then the tide receded. Countervailing forces swooped in. “Political correctness” became a wedge issue, “cultural studies” a joke. Morrison still collects laurels most living authors would happily die for—the latest being the 2006 selection by a panel of top literary figures of Beloved as the best novel of the past 25 years. But two decades after she won her Nobel, Toni Morrison’s place in the pantheon is hardly assured. A writer of smaller ambitions would live on contentedly in this plush purgatory, but Morrison writes—more and more consciously, it seems—for posterity. Having once spearheaded the elevation of black women in culture—Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Oprah—she now finds herself struggling to cut them loose, to admit at long last what she’s always believed: that she’s not only the first, but the best. That she belongs as much with Faulkner and Joyce and Roth as she does with that illustrious sisterhood. That she will pass the test that begins only after Chloe Wofford is gone, and Toni Morrison is all that’s left.

During the forties, for a black family on a run-down block in the steel town of Lorain, Ohio, there was no question of fitting in. Not that there wasn’t integration of a sort. Lorain, and occasionally the Wofford house, was mixed by necessity. “We were mostly poor-ish, and we had no choice except help one another,” Morrison explains. “I remember powerful exchanges”—sampling the Czech neighbors’ cabbage rolls, occasionally sharing a room and even a bed with white boarders.

It wasn’t the South, from which her sharecropper grandparents had fled with little more than a violin and (just barely) their lives. Nor was it quite the sepia-toned portrait of class solidarity that Morrison occasionally paints. Landlord after landlord hounded them out of white areas, and while all the kids played under the 21st Street bridge, the races were apart, eyeing each other across the tracks. Morrison has often spoken of vacillating between her mother’s quiet optimism and her father’s unvarnished hatred of white people.

In school, though, everyone had to mix. “The school was a leveling agent—like the cemetery,” says Jeanne Atanasoff, a high-school friend of Morrison’s who corresponds regularly with her. “But she was way ahead of the rest of us. The whites voted for her for class treasurer!” She was also in the drama club and the National Honor Society. “She was so liked, and she was focused. They didn’t have affirmative action then. She was respected because she was an achiever.” The only way she could fit in was by standing out.

After school, Chloe kept close to home. She and her three siblings would dance to her grandfather’s violin or the songs of her mother, Ramah. “She had the most beautiful singing voice in the world, and she could sing anything,” Morrison says. “People used to come from all around to hear her in church, and go weeping.”

At night her parents told R-rated ghost stories, like one about a murdered wife who returned home holding her own severed head. The following evening, the kids had to retell the tales with variations: Maybe it was snowing, or there was blood dripping from the head. “This was all language,” she says now. There were also fifteen-minute plays on the radio, which “influenced me as much if not more,” she remembers. “If they said ‘green,’ you had to figure out in your head what shade that was. And you only heard voices. So everything else you had to build, imagine. Everything.”

Morrison’s neat, pretty house on the Hudson looks nothing like the squat boathouse she bought in the late seventies, on the same plot of riverbank. “In those days,” she says, “people didn’t move this close to the water. Now it’s like the most expensive property in the village.” A few months after she won the Nobel Prize, the boathouse burned down “to the Earth.” Her son Slade was in the house when an errant cinder leaped out of the fireplace; he escaped, but much of the family memorabilia was gone—a loss that still brings her to the verge of tears.

The house built in its place is warm and colorful, enlivened with African sculptures and tureens and abstract art and a spiral staircase. But there’s something a little too new about it. Though Slade was an abstract painter, none of this work is his; it’s been put into storage. One closet hides an elevator, which Morrison presciently installed not long before her hip replacement in 2010. “I have gotten up to fourteen minutes of walking,” she says. “I go outside, around the decks.” Before she retired from teaching in 2006, Morrison had two other homes, one in Princeton and a skylighted split-level in Nolita. She also owns a couple buildings upriver. And just a few weeks ago, she rented a new Manhattan apartment. She’s attributed her house-gluttony to all those childhood evictions.

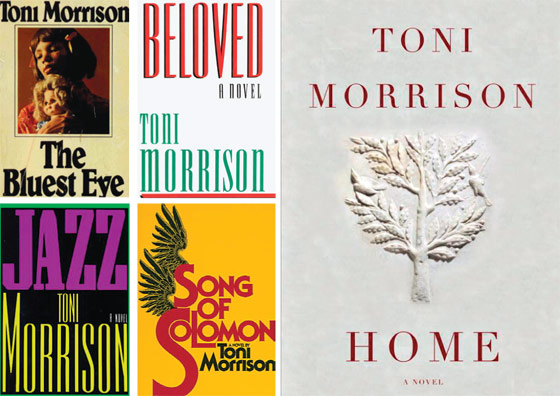

The title of the new novel, Home, refers to Frank Money’s Georgia hometown, which lies at the end of a long, tortuous journey. Traumatized by atrocities in Korea and the Deep South of his childhood, Frank races back to save his sister from a sadistic white doctor. It’s an archetypal postwar homecoming story, reminiscent of The Odyssey. But it’s really about the upheavals that took Frank away from home in the first place, along with a generation of Korean War veterans and southern black migrants, during a supposedly tranquil and homey decade that was, for them, anything but.

Morrison’s fifties were very different from those of her haunted hero. She had opted for college at historically black Howard University, expecting some sort of Utopia for African-American intellectuals. Instead, she found herself in a segregated city (Washington, D.C.), on a campus segregated de facto by skin tone instead of race. The cruelties of racism were starker than in Ohio; even worse was the realization that its victims could be almost as cruel to their own kind. That Morrison’s firsthand political awareness came relatively late might, paradoxically, explain its importance in her work. “I had friends who lived in the South, and they absorbed it, and it doesn’t stand out as foreign to them,” she says. “But it does to me. So I look at it.” Yet it’s only now that Morrison is reexamining that decade for the first time. “Emmett Till was killed in 1955. It was all lying there, like seed corn—the seeds that blossomed in the sixties.”

Home was only half-done when Slade died, around Christmas 2010. Morrison says it was pancreatic cancer—“and recklessness. He was one of those Chinese medicine–type crazy people. Brilliant writer.” He also collaborated with his famous mother on clever children’s books like Peeny Butter Fudge and Who’s Got Game?: The Ant or the Grasshopper? “But [he was] very careless,” she says. “When they get grown, you can’t smack ’em.” The sadness still weighs her down, and lately she’s been dwelling on her regrets, what she calls “the fallout from not being able to save my son.” After Slade’s death, Morrison put Home away for months. It’s the closest she’s ever come to writer’s block. But she would never use the term herself.

“I’m getting a little better,” Morrison says now. “It’s spring, and my forsythias are out. What is saving me from narcissistic wallowing is the book I’m writing, where I spend the liveliest, most confident part of my day.” Her next book is a special comfort at the moment, but writing has always been a solace. “All of my life is doing something for somebody else,” she says—though her children are long grown and she’s been divorced for almost 50 years. “Whether I’m being a good daughter, a good mother, a good wife, a good lover, a good teacher—and that’s all that. The only thing I do for me is writing. That’s really the real free place where I don’t have to answer.”

Morrison’s longtime editor, Robert Gottlieb, can attest to the divide between the private writer and the public figure—a persona famous enough for its ego that Gottlieb brings it up without prompting. “To people who don’t know her, she might appear to be a diva,” he says. “But in the work and personal relationship, there is nothing of that.”

Morrison considers humility a handicap. “It works against you,” she says. She is fond of testing journalists who ask either too little or too much. “You’re writing a little piece, aren’t you?” she asks me. No, in fact; she was told it’s a feature. “Oh, this is too much. Can I approve it?” That’s not really done, I say. “Can I edit it?” I tell her I’ll be nice. “You’ll be nice! You’re gonna tell all these funny stories!” She laughs. Then she tells a few more stories.

“She has an incredibly adorable side,” says Claudia Brodksy, a Princeton colleague and a close friend. “Which I shouldn’t be talking about, because she’s not gonna show it. She’s told me: ‘For the public, I have to be very severe—just keep it at bay. Otherwise they just devour you.’ ”

It was during the fifties that Chloe became Toni Morrison. At Howard, people began calling her “Toni,” and in 1958, she married the Jamaican-born architect Harold Morrison. She got her master’s in literature at Cornell, with a thesis on suicide in the work of Woolf and Faulkner—clear stylistic influences on a novelist who has little truck with the hard realism of her peers in the post-sixties pantheon. She was discouraged from writing on her first chosen topic: the black characters in Shakespeare.

In 1964, pregnant with Slade, Morrison split from her husband. She hasn’t said much publicly about the marriage, except that Harold wanted a more subservient wife. “He didn’t need me making judgments about him,” she once said, “which I did. A lot.” Soon she took a job in Syracuse, editing textbooks for a division of Random House. She began rising at four in the morning, long before daylight obligations intervened, to work on turning a short story, about a black girl who prayed for blue eyes, into a novel.

The Bluest Eye was published in 1970. Decades later, after everything from The Color Purple to the works of Sapphire, the novel’s plot—11-year-old wretch impregnated by father—might seem trite. At the time, though, the tragic story was an important break from the didactic, uplifting black novels that ruled the day. “All of the reviews I had, in the black press and in mainstream media, were silly,” Morrison says now. The former complained about her negative portrayals while the latter dismissed her for trying too hard. But just as The Bluest Eye was on the verge of disappearing, the City University of New York launched a black-studies department and put the novel on its reading list. “Required reading,” Morrison once said about it. “Therein lies the success.”

The political and academic tide was lifting her boat—in writing and also in publishing. She had transferred to Random House’s New York offices in 1968, but was still editing textbooks years later, when Random House president Bob Bernstein found The Bluest Eye in a bookstore. He insisted Morrison publish under their umbrella, and so she met the legendary Robert Gottlieb at Random House–owned Knopf. He would end up editing all but one of her subsequent novels.

Bernstein also made Morrison a trade editor at Random House—effectively his black editor. She produced books by Toni Cade Bambara, Gayl Jones, Muhammad Ali, Angela Davis, and Huey Newton. Her signature achievement was The Black Book, an illustrated coffee-table compendium of documents of the African-American experience: blackface ads, lynching photos, patents filed by black inventors, and news stories—including one about a woman who killed her infant rather than have it sold into slavery. With almost no editorial comment, it achieved something new, presenting African-American history unvarnished—the ugly along with the beautiful.

Morrison the editor had an agenda, as she freely admits. “In my mind, there’s all these people out here marching, talking, writing, or being shot,” she says. “I thought that I was contributing powerfully to the so-called record.” The problem was that the institutions that were elevating her books were still ghettoizing them. A Random House salesman told her he couldn’t sell her books “on both sides of the street.” She learned never to publish three “black” books in a season, because they would all get reviewed together, no matter how different they were. Even John Leonard’s review of The Bluest Eye, the only prestigious rave, grouped it with two other “first novels on race.”

A center island painted in quaint Provençal colors separates Morrison’s kitchen, where a home aide is frying up crab cakes, from the rest of the first floor. Two objects dominate this island. One is a bowl of stones the size of bread loaves. “These rocks are from Thailand,” she says, “and you’re always supposed to know which one is calling to you. So I got three. They looked like they were all calling to me.” Did she ship them in from Thailand? “Oh God, no! They were in some little crappy shop in New York, where they go buy junk and tell you it’s important.”

The other object on the island, which she recently brought in from storage, is her Nobel Prize certificate. “I hadn’t seen it in years,” she says. Mounted on clear plastic, it lies open like a diploma case. Every prize has a different design on the left-hand leaf, and this one is a white U.S. map on a field of black. “I think they were trying to be cute,” she says, chuckling.

When Morrison found out she’d won the prize, in October 1993, she was at Princeton, where she began teaching in 1989. With reporters and hangers-on mobbing her office, she had her assistant call her friend Claudia Brodsky. “Get. Over. Here. Now,” the assistant commanded. Brodsky pushed her way past the throng and was hustled into Morrison’s office. “She closed the door,” Brodsky recalls, “and she just started dancing.” It was coy, silent, and joyous. “I’ll never forget it in my life.”

The Nobel is awarded for an entire body of work; by 1993, Morrison’s was substantial and impressive. The Bluest Eye had been followed by another small-scale work, Sula, at which point Gottlieb—editor of Joseph Heller and John Cheever—encouraged Morrison to go bigger. The result, Song of Solomon, vaulted Morrison into the arms of a broader public. John Leonard declared it “a privilege to review. It may be foolishly fussed over as a Black Novel, or a Woman’s Novel, or an Important New Novel by a Black Woman. It is closer in spirit and style to One Hundred Years of Solitude and The Woman Warrior. It builds, out of history and language and myth, to music. It takes off.” It won the 1977 National Book Critics Circle Award. Gottlieb soon persuaded Morrison to quit her editing job.

Morrison’s last book before the Nobel Prize was the acclaimed Jazz, a sort of polyphonic African-American answer to The Great Gatsby. But it was Beloved, published in 1987, which earned her the Pulitzer Prize and a slot on Stockholm’s short list. Based on that clipping in The Black Book about the slave who killed her baby, Beloved takes place mostly after emancipation, in a house haunted by the ghost of the murdered child. It’s oblique and nonlinear, but also an allegory of America’s shame and a shiver-inducing ghost story. And it came along at an auspicious time. At the height of the culture wars, proponents of broader school curricula were hungry for books that turned “marginal” experiences into art powerful enough to elbow its way in alongside Faulkner and Joyce. Meanwhile, a more liberal public—the children of the seventies—was eager to embrace a heady thriller indicting their nation’s brutal history. (“It’s a stupefying work,” says Brodsky. “It gives you nightmares.”) Beloved was on the best-seller list for 25 weeks and earned a permanent place on school reading lists.

But before winning the Pulitzer, it was snubbed at the National Book Awards, prompting 48 black writers and critics to sign a letter of protest to the New York Times. It was probably a counterproductive move, ammunition for a range of detractors—from canon-hugging neocons to black contrarian Stanley Crouch, who called it a “blackface Holocaust novel”—suggesting the accolades were affirmative-action tokenism run amok.

“It’s hurtful,” Morrison says now. She remembers that the Times reported the Nobel, the first for an American-born author since 1962, as “a controversy—a controversy!” Morrison saw it differently, of course. “I felt profoundly American, flag-waving,” she says, “but you’re never out there as somebody from Ohio, or even as a writer. Because all that is clouded by the box you’re put in as a Black Writer.”

Brodsky, with her brusque New York twang and quadruple-espressos, is never at a loss for words—except when I ask her why Morrison’s difficult novels became so explosively popular. “I’m actually gonna think for a minute,” she says. “No one’s asked me that question.” After more than a minute, she says, “If she were not a black woman, then you would say, obviously, the work.” After another minute, she brings up “Mr. Jeremy Lin. Anything that’s just not there, all of a sudden, this complete craziness happens to people who just never existed. Then it’s, ‘We’re gonna hold back his injuries so we can sell more tickets.’ And this guy is just gonna get refuse dumped on his head for the rest of his life if, after playing for a month and a half in the NBA, he doesn’t again beat Kobe Bryant by 38 points. You know what I mean?”

Brodsky’s apologia is for both Morrison’s success and its aftermath. Even as her sales and status have held strong, Morrison’s books have ceased to qualify as news. She says she was lucky to be working on Paradise when she won the Nobel—to avoid the writer’s block a friend calls “the Stockholm curse.” But critically, at least, she did succumb. Neither Paradise nor her next novel, Love, met the bar raised by Beloved and Jazz (never mind the Nobel Prize).

Both Philip Roth’s American Pastoral and Don DeLillo’s Underworld came out in 1997, the year Paradise did. Both addressed historical eras and themes, as Morrison does, but both spoke directly to contemporary anxieties in a way that Paradise did not. Roth and DeLillo were nostalgic for an old American consensus and alarmed at its disintegration, and both used voices resonant with modern paranoia and neurosis. In contrast, Morrison still seemed to be in cross-racial dialogue with the same long-dead Modernists on whom she’d written her thesis in the fifties.

It must have galled Morrison that James Wood’s long takedown of Paradise in The New Republic fell under the headline “The Color Purple,” alluding to Alice Walker’s pulpy southern black chronicle. Comparisons to Walker and Maya Angelou bother her, not only because they put her back in the Black Writer box but also because she feels demoted. “The first book of Maya’s I really enjoyed, and Alice has written at least one, maybe two books that I admire a lot,” she says. But “they’re very different writers, very, very different from me.” How so? “Well, one self-edits and one doesn’t.”

Morrison and Walker do share a link: Oprah Winfrey. After starring in the blockbuster movie adaptation of The Color Purple, Winfrey was just becoming a talk-show megastar when she optioned Beloved in 1988. In the decade between the deal and the movie’s release, she started a book club and included Morrison’s books. She also began touting a succession of self-help mentors. Morrison was arguably the first author Winfrey devoted her starmaking power to—and probably the most ambivalent. She told friends she didn’t want Beloved to be a film, and she prayed Oprah wouldn’t play the lead. Oprah did, and it was a notorious bomb, which Morrison didn’t like. (Now she denies ever being apprehensive about the movie.)

Morrison’s ambivalence spilled over recently when Oprah broached the death of Morrison’s son. During her last month of TV shows last year, Oprah invited her “most memorable guests” back to share “life-changing lessons.” Still in mourning, Morrison consented to be flown into Chicago on a private jet and put up at the Four Seasons. But she bristled when Oprah suggested the show would help her get “closure” on Slade’s death. “Don’t ever say that word,” Morrison said. “There’s never closure with the death of a child.” She says now that she was happy to discuss her son, but not in detail. “There’s no language for that”—especially not the language of closure. Oprah is “a generous woman,” she says, “but I did want to say—the guarantee of happiness? What is that about?” Certainly nothing that Faulkner or Woolf had anything to do with.

There are less personal reasons why Morrison might be interested in distancing herself from Winfrey and the school of lyrical uplift. In colleges, she worries about being a slave to intellectual fashion. She remembers visiting the University of Michigan a few years ago and perusing its course catalogues. “My books were taught in classes in law, feminist studies, black studies. Every place but the English department.” Since then, she’s encouraged work that ties her to older departments like classics, and even sits in on academic lectures about her—both as subject and guest of honor.

Brodsky believes Morrison’s insecure place in academe is symptomatic of a deeper cultural problem. “White women have a very strong—‘You are the wise black women who will take care of my innermost’—relationship with her,” Brodsky says. “They’re like, ‘How dare she not be this mammy?’ That [role] works if there’s one book and it’s life-affirming in this very obvious way. I think it’s because you can’t quite mammy-ify her entirely that there’s a great resentment.”

Morrison has written two novels since Paradise and Love. A Mercy was a deliberate effort to transcend racial politics: a lyrical work set in early Colonial Virginia, “a place before slavery was equated with race.” Home is a very different kind of book: a linear, stripped-down narrative about racist brutality. More than most writers in late life, Morrison defies any kind of narrative arc about the direction of her work.

The next novel looks like another zigzag. It’ll be her first foray since the lesser-known Tar Baby into contemporary times and themes—perhaps even a poach on DeLillo territory. She won’t discuss it in detail but says it “is about a certain kind of intellectual, an artistic intellectual. All the men I know are intellectuals,” including Slade, “but I’ve never written about them.” Another character is deeply into fashion, which is why Morrison is currently fascinated with Lady Gaga. “She’s done it,” Morrison says approvingly. “Fashion with a capital F.”

After our talk, Morrison walks me to the back window, which overlooks a pier on the river. It’s brand-new; the old pilings blew away in a storm last year. “It’s stronger now than my house,” she says. So is an incongruously colorful bench on the dock, donated by a scholarly fan club known as the Toni Morrison Society. “A bunch of kid artists” decorated it, making it look more like an MTA-commissioned piece of public art than the setting for a literature Nobelist’s quiet contemplation. “I thought, Oh great, it’ll fade in the weather, and it won’t look so cartoonish.” But the man who built the dock told her it wasn’t outdoor wood; they had to lacquer it. So the bench, with its childlike tms scrawled over the back, might well outlast its famous occupant.

Morrison parries questions about posterity, about what becomes of Toni Morrison after Chloe Wofford passes on. “I do think about what they call ‘my papers,’ ” she says. She told her older son, Ford: “Put them someplace where no one can write some stupid biography.” Last year she canceled a contract for a memoir: “I am not interesting to me. There’s no discovery there.” She declines to correct Who’s-Who directories, and she’s repeatedly turned down offers from Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s project to trace the roots of African-Americans. She’d rather preserve a sense of mystery—the source of fiction, after all. And if the biographers insist on knowing, she says, “I think I’d prefer they got it wrong.”