For over twenty years, Chris Whittle has been doing his best to teach the rest of us that schools ought to be run as businesses and education treated more like a product. Now he finally has his flagship store. Avenues: the World School opens this week amid the flashy condos, galleries, and public housing of West Chelsea—a retail-sleek, nearly $40,000-a-year nursery-through-college-prep institution with a bland name that vaguely evokes upmarket urbanism, and a customer base (the parents) who see themselves as early adopters, hoping the school will provide a secure future in the Davosphere for their children. Others are just impatient with—or excluded by—the admissions rituals of the city’s traditional private schools.

“We didn’t really do it for the meaning. We did it because it traveled really well,” Whittle says of the school’s name as I arrive, then introduces me to Avenues’ “creative director,” a branding guy named Andy Clayman. Whittle’s scrutinizing a video wall atop the main staircase that the kids will partially control; it features pictures of students linked together like digital Tinkertoys under the words “We Are All Connected.”

The screen later flips to show a gigantic Google Maps view of Beijing, menacingly orthogonal. Whittle has just returned from there, where he’ll be opening the second branch of the Avenues global network. They’re planning at least twenty schools, in the usual capitals of capital: London, São Paulo, Mumbai, Singapore, Abu Dhabi. He studies the Beijing map to try to find the school’s address by the Sixth Ring Road.

The school has pitched itself aggressively as a kind of boot camp for “global preparedness,” and students must spend a portion of their day learning in Mandarin or Spanish. For now, no other languages are taught. As Boykin Curry, a hedge-funder whose child with very social interior designer Celerie Kemble will attend, puts it, “It’s the only school we could find where our children will spend half their day speaking Mandarin, which seems important if you want to be able to talk with your company’s central headquarters in twenty years.”

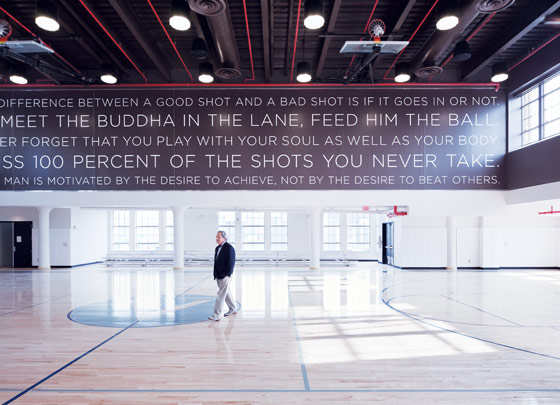

All the signs around the school are trilingual, and many of them are designed to be thought-provoking in that inspirational-advertising way banks and oil companies have come to perfect. On the doors to the gym: play, participate, strive; on the cafeteria: renew; on the music studio: explore.

Whittle looks exhausted. Avenues has been a marathon sales job, from working the investors who backed it with $75 million to persuading gray-haired credibility-giving big shots who’d worked at Hotchkiss, Exeter, and Dalton to climb aboard, to smooth-talking parents. Before there was a mission statement, there was a logo—half of a globe, an open book on top completing the circle with its riffled pages. This became ubiquitous in the marketing, designed to give an air of inevitability to the school—not only that it would open but that it would be a solid Ivy launchpad. As a welcome-to-school video promises, students will be “at ease beyond their borders … artists no matter what their field … emotionally unafraid and physically fit.” Plus Suri Cruise is enrolling.

Other than language, the big marketing point for Avenues is that it focuses on student “mastery.” To some, that might sound airily meaningless (“We will support any passion … at the Avenues school. We know that really in-depth mastery provides important transferable lessons, which is long-lasting in self-esteem”), but to Avenues parents, it sounds like: We’ll figure out how to brand your kid for college.

That Avenues is a for-profit school seems to fit right in with that savvy calculation by the parent body, many of whom are foreign-born and members of what one prep-school admissions counselor calls the “transient financial class.” (Who needs a stuffy school, a century old and all the way up on the Upper East Side?) Of course, many parents want something with a track record at this price and wonder if it’s all a bunch of high-concept sales blather—and if they’ve done any research at all about Chris Whittle and his visionary habit of flying too close to the sun, that seems possible. An entire 1995 book called An Empire Undone was written about his business adventures (notably his pilloried Channel One, which gave schools free TVs in exchange for showing an in-classroom ad-supported news show). He spent about sixteen years helping pioneer the charter-school movement with his for-profit education firm Edison Project, with only mixed results. There, he contended with teachers’ unions, local politics, and schools that were full of poor kids to try to show he could make money while improving scores. He was pushed aside in 2007, but seems earnestly committed to Avenues as a private-school extension of what he calls “the Movement.” “It is liberating. You can do exactly what you want. There is virtually no regulation on a private school; you’d be stunned,” says Whittle.

But despite the prurient interest among status-obsessed New York parents (“Move Over, Dalton” wrote the The Economist last week), it is in many ways less like the prep-school academies it shares a tuition price with and more like the charter school of Whittle’s dreams—sleeker, better funded, unencumbered by public oversight, and less compromised by education as public service than those he helped run at Edison. At those charter schools, the per-student budget was about $8,000 and Whittle has planned Avenues with a McKinsey-like focus on making the curriculum as lean and efficient as possible. As much as the flamboyant condo buildings it neighbors on the High Line, the school is a symptom of the teeming niche affluence of Bloomberg’s New York.

“I view this as the last rodeo,” Whittle says as we sit in the school’s third-floor cafeteria, which overlooks the park and feels a bit like the offices of an advertising agency, with proper seating and none of the old fold-and-roll picnic tables. The once boyishly Gatsby-like Whittle is now 65, his hair still a bit floppy, his trademark bow tie intact. Tennessee-bred, he got rich creating a series of advertising innovations—special magazines for college students, Datsun owners, and doctors’ offices—and made a splash in New York in 1979 when he and a college friend Phillip Moffitt bought a woozy Esquire. Whittle knows how to make friends (he’s an irresistible dinner companion and a Four Seasons regular; the best man at his wedding was Time magazine managing editor Richard Stengel); knows how to live just beyond his means (very expensive architect Peter Marino decorated most of his houses and even designed the lavish Knoxville headquarters of now-defunct Whittle Communications); and has a knack for hiring established people to lend his upstart ventures their prestige.

He likes to think of Avenues as the summation of an interest that dates back to his first education-reform conference, in 1967, when he was in student government at the University of Tennessee and fighting for things like courses “more relevant to our lives” (as well as to ease the curfew on women’s dorms, in the name of increasing student liberty). “Private schools have a lot to learn from public schools,” he says, citing especially the benefits of frequent assessment (an idea from the era of market-minded, testing-driven school reform that gave us No Child Left Behind). “If you go back to the very first announcement of Edison, it was to do the first national network of private schools,” Whittle says. There were to be 1,000 of them, at a cost of billions, and he convinced the then-president of Yale University, Benno Schmidt (now the chairman of Avenues), to join him in the project. “And we were working on that when the idea of charters emerged, and some governors came to us and said, ‘If you do publics, we’ll give you the freedom to do them through charters.’ But it didn’t turn out that way.” He gives a quick, rueful laugh.

In 2005, as Edison was tottering, he wrote a book called Crash Course: Imagining a Better Future for Public Education, which was often martyred in tone (with section titles like “Start Big, for There Will Be Those Who Will Bring You Down”), used lots of war metaphors, derided the existing school system as being a “cottage industry” that teaches in “Middle Ages” classrooms, and argued that “schools of the future will have an embedded culture of outrage.” He railed about how big pharmaceutical and aviation companies have huge “research and development” budgets, while education doesn’t. Whittle has always been a blue-sky brainstormer type, and it’s easy to see that he is a highly motivating boss, but his book is largely for the type of person who thinks principals should have M.B.A.’s and teachers should get commission, their bonuses dependent on improvements in test scores. Understandably, teachers unions weren’t happy about that idea, or his other big one, which is to free up money for raises by having fewer teachers.

But the book was also driven by a desire to improve the lives, or at least the scores, of underprivileged children, and it was most rousing when he asked the sort of question that is usually only asked rhetorically by people, like him, who summer on Georgica Pond: “Is it possible that somewhere inside us we don’t want everyone to be well educated?”

Where exactly Avenues fits into the ecosystem of New York City schools isn’t yet entirely clear. It offers financial aid even though, not being tax-exempt, the money comes from its bottom line. (Whittle says 10 percent of students get aid, about 5 to 10 percent less than at an established independent school.) Its language immersion is unusual, as is the “world course,” a social-studies curriculum that, Whittle insists, will be offered to every student in every country without national bias. Its centerpiece science program, robotics, is a staple at the city’s specialized high schools—Stuyvesant, Bronx Science, Brooklyn Tech—but is not very common at New York prep schools. Avenues is unusually devoted to the idea of globe-trotting study—if and when all the campuses are up and running, every student from middle school up will spend part of the year abroad, and there is a lot next door where Avenues hopes to build a dorm for visiting pupils. But most prep schools now offer study-abroad programs. Avenues claims somewhat higher average teacher salaries—over $100,000 a year—and while tuition is typical for a private school, several parents pointed out to me that since the school is for-profit, they won’t be hounded for donations, too.

What is definitely different is the building, a solid, elegant Cass Gilbert–designed 215,000-square-foot former grocery wholesale warehouse built in 1928, which was fitted out inside by Bonetti/Kozerski Studio, best known for its luxurious shops for Donna Karan and Tod’s. “Chris wanted someone who hadn’t designed a school before,” says Enrico Bonetti, but the architects were also inspired by a few schools they admired—Dalton, for its food service; Trinity, for the lobby.

We’re standing in a lower-school classroom, and Whittle points to a tyke-size swivel chair. “A lot of time went into this,” he says. “If you have children who like to move, then you don’t have to get up and run around. So these chairs help them use that up. There was a whole team who did nothing but furniture selection.”

He takes me up to the rooftop playground, then down to the arts-and-science floor, which has a glass-walled robotics lab right off the elevator bank (“We try to place interesting things where they can be seen”). Elsewhere, he points to the eyeball-stalk surveillance-style cameras that he says will allow the kids to teleconference with other continents. It was his idea that the classroom doors should open in the middle, not to the front or the back, to challenge the teacher-student hierarchy. Along the south side of several floors are what he describes as “soft-chair lounges for students” for reading and group work. He shows me the server room, which can service up to 5,000 devices (everyone gets an iPad), a little stage for the lower school to put on plays, the coffee-bar landing pad for helicopter parents off the lobby. The upper school “student commons” is a sunny, two-story space with vintage-looking leather sofas and “work stations”—each kid gets a dedicated cubicle, since Whittle thinks they should spend half the day out of the classroom working independently (a pedagogic notion he pursued in Crash Course as a way to save money). “They are in some way modern-day libraries,” Whittle says. Avenues—which Whittle wants to be ultimately paperless—does not have a central library.

In the entryway for the nursery school, the walls are covered in simple drawings of simple things—a shoe, a cat—by Maira Kalman. The top-floor gym features inspirational slogans on the walls that could be codas for everything Whittle has ever tried and tried again. Biggest is the phrase “You Miss 100 Percent of the Shots You Never Take.”

The week before the school opened, there were three nights of receptions for the parents. (And yes, September 4, Katie Holmes was there.) “We’re pumped, and we’re ready,” declared Skip Mattoon, the sixtysomething co-head of school, formerly of Hotchkiss. “We have a curriculum based on best practice. We have a soaring mission.” And a certain amount of nerdy jocularity. Gardner Dunnan (formerly of Dalton), the academic dean and head of the upper school said, “A recent letter I wrote to you, and some of you actually read, I addressed to ‘pioneer parents.’ And all parents are pioneers, but parents of the ninth-graders are really pioneers.” This year, freshmen are the oldest students to give the college-admissions machinery time to get going. The school opens at about half-capacity, with 725 students. He adds, “You are making a bet that we can deliver a superior upper-school curriculum. We are confident that we can do that, but you’ve been really courageous. We’ve been really cowardly. We were very, very selective in admitting ninth-graders, because we knew that they are going to define how this school is viewed over the next decade.”

Whittle got up, looked around at this finally opened department store of his dreams. “It shows what can happen in life and how workable life is,” he says.

Circulating with the cheese plates, I meet Susan Schuman, a handsomely coiffed woman in a black suit and pink sandals. She is the CEO of management-consulting firm SYPartners (according to its website, Schuman helps executives “define—and then attain—greatness for their companies”). She praises Avenues as a “start-up” that seeks to “disrupt.” I ask her if she worries they’ll cut corners to meet their profit margins. “I don’t know. The thing that gives me hope is their plan to diversify to other countries.” This, she says, will help “their business model.” “Even if they only do half of what they are saying they’re going to do, it’s still going to be great,” says Ilene Osherow, Schuman’s ebullient life partner.

As they wander off, I turn to James Wynn, who also works for SYPartners and lives in Brooklyn. “We really didn’t want to send our kids to school in Manhattan,” he says. “We went to this one open house, and there was a line around the block. We took one look and said, ‘This is absurd. This cannot be this important.’ ” Then Schuman told him about Avenues. “I like the fact that they are taking a risk and doing something different. They went out and raised all this money to make this private school, and they made a lot of choices that I would have made if I were starting the school. I’d build a building on the High Line. I’d hire the people they’ve hired.” He looks over to the marble-clad serving counter. “I like white marble in my kitchen too. I’d love to have my kitchen look like that. I like the decisions they’ve made. Why not? I’m game.”

The inspirational mural at the Avenues gym. Photo: Dean Kaufman

Photo: Dean Kaufman

Photo: Dean Kaufman

Photo: Dean Kaufman

Photo: Dean Kaufman

Photo: Dean Kaufman