There may be no greater testament to David Brock’s central role in the vast left-wing conspiracy than the lengths to which Rupert Murdoch will go to avoid him.

In November, a researcher at Media Matters for America, the liberal press-watchdog group that Brock founded seven years ago, noticed that the website Charitybuzz was auctioning a “friendly lunch” with Murdoch to benefit the Global Poverty Project. That one of Brock’s worker bees would be keeping tabs on the News Corp. chairman’s calendar should not be terribly surprising. At Media Matters’ headquarters in Washington, D.C., scores of headphone-wearing staffers spend their days (and nights) staring into their television screens and computer monitors, waiting for the latest bits of “conservative misinformation” to emerge from the Fox News Channel and other corners of the right-wing media landscape, all of which are saved on “the big TiVo”—270 terabytes’ worth of hard drive that store over 300,000 hours of TV shows—so that the offending clips can be uploaded to Media Matters’ website. Are you in need of a compendium of the “50 Worst Things Glenn Beck Said on Fox News”? Fear not, Media Matters’ site has one.

But in the past few months, the group has begun to do more than merely monitor Fox’s programming. “What happened after the Obama election, I think, is that Fox morphed into something that isn’t even recognizable as a form of media,” Brock recently told me. “It looks more like a political committee than what it looked like pre-Obama, which was essentially talk radio on television. It’s more dangerous now; it’s more lethal. And so as Fox has doubled down, we’ve doubled down.” In practice, that means no longer just pointing out inaccuracies. Instead, Media Matters is going on the offensive.

“The truth is that the more responsible the media outlet, the more responsive they are to constructive criticism. But with a Sean Hannity, you can correct the same lie ten times and he’ll keep saying it, so you reach your limits with what you can do defensively,” Brock continued. “Now the idea is: What does it take to get the attention of people above the News Channel? What does it take to get the attention of Murdoch?”

Having the media mogul as a captive audience over lunch certainly seemed like one way to do that. So when the charity auction was brought to Brock’s attention, he told one of his deputies to “go get it”; $86,000 later, Brock had bought the opportunity for himself and five guests to break bread with Murdoch. But Murdoch apparently began to have second thoughts. For months, Media Matters was unable to schedule the lunch. Then in March, Charitybuzz passed along demands that Brock and his guests submit to “a full background check” and promise not to record or report on the conversation.

Media Matters balked at these conditions—proposing instead that Brock and Murdoch select a third-party journalist to attend the lunch and report on their interactions. But Murdoch refused. Finally, last month, News Corp. informed Charitybuzz that Media Matters’ anti-Fox agenda meant the “very high likelihood that the lunch would be neither friendly nor productive”; the company would donate $86,000 to the Global Poverty Project instead. In other words, while Brock was willing to pay $86,000 for the privilege of having lunch with Murdoch, Murdoch was willing to pay that much in order not to have lunch with Brock.

In politics, there is no such thing as a lonely apostate: The very act of betrayal makes a political figure instantly irresistible to his new comrades. When the ex-Communist spy Whittaker Chambers publicly accused Alger Hiss of having been a fellow traveler—first in testimony before the House Committee on Un-American Activities in 1948, then in his memoir Witness—he became a hero to a generation of conservative politicians and intellectuals. The Democratic senator Zell Miller earned himself a spot as the keynote speaker at the 2004 Republican National Convention for denouncing his party. And for the past three decades, David Horowitz has made a living as a right-wing commentator by repeatedly renouncing his past as a member of the sixties New Left.

And then there’s David Brock, who made his name in the early nineties as an investigative reporter for The American Spectator and a self-described right-wing hit man. The bigger the liberal target, the bigger the teardown job. Anita Hill was, in Brock’s infamous estimation, “a bit nutty and a bit slutty”; in a lengthy exposé on Bill Clinton’s sexual romps back in Arkansas, Brock mentioned one at a Little Rock hotel with a woman named “Paula”—which eventually led to Paula Jones’s sexual-harassment lawsuit, which almost ended Clinton’s presidency. Off the page, Brock reveled in his reputation as a destroyer of liberal icons. He ostentatiously smoked a pipe and swaggered around Washington with a walking stick (affectations made even more ridiculous by the fact that Brock was still in his twenties); callers to his home phone during the Clinton administration were greeted by the answering-machine message “I’m out trying to bring down the president.”

Brock’s decision to abandon conservatism was a gradual one—and, unlike other famous apostates’, more personal than ideological. “I didn’t wake up one day and say, you know, ‘Supply-side economics doesn’t make sense,’ ” he says. In fact, his move from the right began after he failed to deliver the goods in a book about Hillary Clinton and some of his conservative friends expressed their displeasure with his efforts. Brock, in turn, began to suspect that these friends valued him only for his ability to destroy liberals—and possibly loathed him because he is gay.

But, like the most successful of his predecessors in political apostasy, Brock set out to make his departure as dramatic a spectacle as he could. In 1997, he wrote an article for Esquire titled “Confessions of a Right-Wing Hit Man,” in which he declared, “David Brock the Road Warrior of the Right is dead.” To drive home the point, the piece was accompanied by a photo of Brock bare-chested and tied to a tree with kindling at his feet. Another Esquire article followed, this one an open letter to Bill Clinton, in which he asked, “What the hell was I doing investigating your private life in the first place?” Brock’s ultimate break with conservatism came in his 2002 memoir—a raw, angry book called Blinded by the Right. In it, he not only declared his ideological independence but also attempted to lay waste to the reputations of his erstwhile conservative friends—outing Matt Drudge, accusing Clarence Thomas of lying under oath to Congress, and dubbing Ann Coulter, (then-conservative) Arianna Huffington, and Laura Ingraham “right-wing fag hags.” Of course, Brock didn’t exactly spare himself, either, revealing everything from his occasional suicidal thoughts to the “torrid affair” he had conducted in high school with his “sophisticated raven-haired journalism teacher.” When Drudge retaliated by reporting on his site that Brock had written some of the book from a mental ward, a claim that Brock denied, it seemed as if the soap opera would never end.

Brock then: “I kill liberals for a living.”

Brock today: “Fox is more dangerous now; it’s more lethal—and so we’ve doubled down.”

But then, remarkably, it did. For the past decade, in his current incarnation as a progressive activist, Brock has strived to be anything but dramatic. Unlike Horowitz, who attempts to stay relevant by publicly fulminating against his old compatriots, Brock has taken a more difficult path—trying to master the inside game in a war against his former allies.

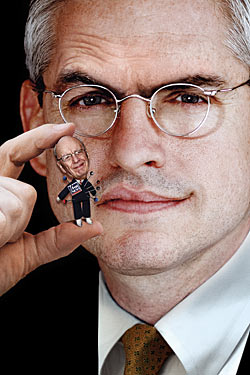

Brock is now 48, and his dark hair is streaked with gray. He is short and slight and still dresses stylishly, though he’s given up his dandy shtick: With his silver-framed glasses and Burberry suits, he looks like a prosperous tax attorney. Anxiously perched on a sofa in Media Matters’ conference room one recent afternoon, he speaks deliberately, seldom raising his voice or even moving his hands, as if he fears one intemperate or ill-chosen word could undo all of the hard work that has gone into his reinvention. “When I founded Media Matters, there was another model, which would have been to call this the Brock Report,” he says. “But I was much less interested in my own profile by that point, because I had already done that once, and it was not terribly fulfilling at the end of the day.”

All the effort he once spent cultivating his public reputation has been channeled into cultivating Media Matters’. “I’m an incredibly hard worker, I’m incredibly tenacious, and I’m incredibly detail-oriented,” Brock explains. He often plans his vacations with his boyfriend, James Alefantis, around visits to wealthy liberals who might donate to the organization. And whereas he used to think of himself as a conservative action hero—“I kill liberals for a living,” he once declared—he now reaches for a more mundane analogy to describe his role on the left. “I’m kind of a builder of institutions,” he says. “I think I’ve got some ability to look at what’s out here, look at a playing field, and identify gaps and niches.”

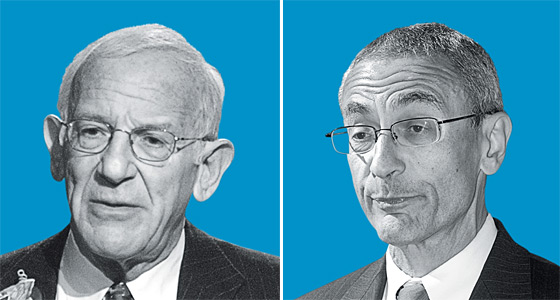

If you talk to Brock’s liberal admirers, however, that humble self-assessment is true only in the sense that Christopher Wren was a builder. In recent years, a certain cohort of Democratic politicos and donors has been engaged in an ambitious project to create liberal analogs to conservative groups like the Heritage Foundation, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Media Research Center. This crowd talks about “patient money” and “a permanent infrastructure,” and they dream of a network of well-funded liberal nonprofit institutions that exists outside of—and therefore bolsters—the Democratic Party. Along with John Podesta, Clinton’s former White House chief of staff who now heads the Center for American Progress, Brock has been the central figure in this effort.

“I don’t know if anybody has a better understanding, in the broader context, of how institutionally we have to go about building a more politically potent force for the progressive movement than David,” explains former Senate majority leader Tom Daschle. Paul Begala, the former Clinton aide who used to cross swords with Brock, says of his onetime nemesis: “I think he’s made himself nearly indispensable to the progressive movement. If he tells you it’s Easter, dye your eggs. The son of a bitch is never wrong.”

The story of Brock’s successful reinvention is, in some ways, a story of serendipity: Right around the time liberals were trying to build a political infrastructure that rivaled the one conservatives had created, along comes someone who’d spent years in the belly of that beast—and was willing to share everything he’d learned. “The liberal side is incredibly envious of the machine the right wing built,” says the left-wing media critic Eric Alterman. “Brock saw it from the inside, and he knows the secrets. He heard what Grover Norquist was saying after the reporters left the room.”

But it’s also a story of meticulous planning and exceptional diligence. “David is pure strategy,” says his friend the literary agent Will Lippincott. “He is constantly thinking about how to make things work. He sets goals and then he figures out how to achieve them. And he does so methodically and with a great deal of care.” Brock quickly concluded that the most useful contribution he could make to the left—and his best shot at securing a prominent perch in the emerging political infrastructure—would be to create an organization to police journalism. But first he would need to win over the very people he’d spent the previous decade savaging. When Brock was beginning to write a business plan for Media Matters in 2003, Alefantis suggested he seek advice from the liberal legal doyenne Judith Lichtman, whose daughter had grown up with Alefantis. “After James called Judy, I literally went upstairs to the library and got The Real Anita Hill and looked up Lichtman in the index,” Brock recalls. “There were fifteen references. And we were like, ‘Oh, shit.’ ” When they later met, the first thing he did was apologize.

No amends were more important than the ones he made to Bill and Hillary Clinton. “It wasn’t that he wanted forgiveness from the Clintons,” one Brock friend says. “He wanted in. He wanted to be part of this progressive restoration, and the only way he could do that was to seek reconciliation from the Big Dog and his wife.” Brock appealed to the Clintons through their confidants, especially the former journalist and White House aide Sidney Blumenthal. He also addressed the couple in print—not just in Esquire, where he apologized to Bill for “conspir[ing] to damage you and your presidency,” but also in between the lines of Blinded by the Right. Brock says he wrote his memoir, in part, as a form of personal catharsis, but it’s easy to read it as a love letter to the Clintons, repeatedly validating their contention that a vast right-wing conspiracy had sought to bring them down.

It wasn’t long after the book’s publication, in March 2002, that Bill Clinton began pressing copies on people like Daschle and the heavyweight donor Steve Bing, both of whom eventually became crucial early supporters of Media Matters. “His sending of that book out was a big help in terms of door-opening,” Brock says, speculating that Clinton passed it on to “dozens,” maybe even “hundreds” of people. When Brock eventually was invited to meet with the former president in his Harlem office, he noticed an entire cabinet was filled with copies of Blinded by the Right.

With doors opened, Brock got busy with what has emerged as perhaps his greatest talent: persuading rich liberals to give him their money. Last year alone, he raked in $23 million for Media Matters and its affiliated groups. Brock’s fund-raising prowess is the stuff of legend—and some mystery—on the left. He explains it as simply a question of having the right attitude. “I think that you genuinely have to enjoy the interaction with donors,” he says, noting that he solicits their advice on everything from political strategy to management techniques.

But Brock’s greatest fund-raising tool is his personal story, and Blinded by the Right plays the same role for today’s rich liberals that Witness played for conservative intellectuals a half-century ago. Peter Lewis, the billionaire who gave Brock $1 million to help get Media Matters off the ground and has been a major donor ever since, says he was initially inspired to contribute because he’d read Brock’s memoir. “Seeing the things he couldn’t deal with over there on the conservative side and then being abused because of his sexual preference—his whole story was just compelling to me,” Lewis says. Other major contributors to Media Matters tell similar tales. “His having been among the right and rejected them is really emotionally comforting to donors,” says Brock’s friend Jon Cowan, who heads the progressive think tank Third Way. “They know he’s damn good at what he does, but it also means a lot to them that he hates the right as much as they do.” One Democratic politico who has chased after some of the same money says that Brock is simply a captivating character: “The tortured gay intellectual and dark complicated figure who wrestled with his soul. Some of it is cultivated, some of it is real, but man, is it a good fucking show.”

Brock has used his buck-raking ability to turn Media Matters into a political force. What began in 2004 as a ten-person shop with a $3 million annual budget now has around 90 employees and plans to spend $15 million this year. In a fancy office building on Massachusetts Avenue, the organization’s researchers work in six-hour monitoring shifts, from five in the morning till one at night, watching Fox or listening to talk radio in the hope that Rush or Sean or some other conservative yakker will step in it. They’re seldom disappointed. “I knew that as soon as you started shining a light on these people,” Brock says, “there was enough outrageous and despicable and offensive and false commentary that you could make a splash.”

Think of any conservative-media scandal of the past few years—from Don Imus’s “nappy-headed hos” comment to Dr. Laura’s N-word rant to Mike Huckabee’s slip that Obama had “grown up in Kenya”—and it’s a good bet that a Media Matters researcher flagged the offending clip, uploaded it to the group’s website, and got the party started. “They would essentially listen to Limbaugh and watch Beck for us,” says the former MSNBC anchor David Shuster. “There were times Beck would say something outrageous, we’d hear about it, and we’d be able to find the clip because Media Matters already had it. They were an invaluable resource.”

Part of Media Matters’ strength is its staff’s almost unfathomable endurance. “People who work here have to have a personality that enjoys getting angry watching Fox for six hours every day but then being patient enough to want to fact-check every second of it,” explains Ari Rabin-Havt, Media Matters’ executive vice-president. The group demands accuracy from those staffers. Last year, according to Rabin-Havt, Media Matters produced 20,000 pieces of content and issued only 24 corrections. “There’s the expectation that you can’t get something wrong,” he says. “There are consequences for mistakes. One person was fired for an error last year.”

“Do you think David Plouffe and David Axelrod are going to let David Brock build an empire?”

All of this has earned Brock the grudging respect of a group that once loathed him no matter what political team he happened to be playing for: journalists. When he founded Media Matters, Brock concedes, “there was clearly a lot of baggage that I had from the past. Could someone who had admitted fatal journalistic errors set himself up as an arbiter of media criticism? It sounds counterintuitive.” At the Republican and Democratic conventions in 2004, political reporters literally threw Media Matters press releases back at the person who was handing them out.

But over time, Brock and his group have come to be viewed as relatively responsible arbiters. “They beat the shit out of me in 2008, but it was fair, and I made sure not to make that mistake again,” says Shuster, who was suspended from MSNBC that year for accusing Hillary Clinton of “pimp[ing] out” Chelsea. “Some people like to describe David as a partisan, but I think of him as the consummate ombudsman.”

Of course, there’s only so much glory to be had in accurately transcribing Sean Hannity’s latest whopper. And so Brock, for his new crusade against Fox, plans to assemble a team of lawyers to assist former network employees, and others who have clashed with the network, with legal actions they might want to take against the news channel. He recently hired Ilyse Hogue, who, as MoveOn.org’s former director of political advocacy, has plenty of experience with pressure campaigns. “We want to drive up the cost of Fox for Rupert Murdoch and the News Corp. board of directors,” Hogue says one day in her office, which is dominated by a large white board containing her team’s latest brainstorms: persuading Alwaleed bin Talal, the Saudi prince who’s the second largest News Corp. shareholder, to divest from the company over Fox’s coverage of Muslims; reaching out to the cast of Glee to protest the news channel; etc.

Brock has also brought on two journalists who will make Fox their beat, developing sources and producing scoops—a move that’s led to a Media Matters web feature called FOXLEAKS, which publishes internal Fox documents designed to embarrass the network and, perhaps more important, exacerbate Roger Ailes’s already overdeveloped paranoia. “We’re sitting on a number of e-mails that we’ll put out when the time is right,” Rabin-Havt promises.

Last month, Media Matters scored what it considers to be its biggest victory to date against Fox when the news channel and Glenn Beck decided to end his show. Beck had become the face of the Media Matters anti-Fox campaign. Not only did the group keep a running tally of Beck’s most offensive statements, but it was also part of an effort to persuade more than 300 advertisers to boycott Beck’s show—which, Brock believes, is what ultimately convinced Fox that it could no longer afford to have Beck on its air. With Beck’s departure, Media Matters has lost a useful bogeyman, but the episode served to demonstrate that the pressure strategy is paying off. Indeed, Brock received the news of Beck’s departure just as he was about to walk into a meeting with potential donors at a hedge fund in midtown. “I told them right away,” he recalls. “I thought it was a pretty good opening story.”

The question for Brock, though, is whether Media Matters, even with its increasingly grandiose ambitions, will be enough to satisfy him. “David wants to be a kingmaker in Democratic politics,” says one Democratic strategist who’s friendly with Brock, “and Media Matters is not sufficient to do that.” Recently, Brock started Equality Matters, an affiliated group devoted to gay issues, and Message Matters, which produces talking points for liberal activists and politicians; he also helped create an organization called the Progressive Talent Initiative, which seeks to incubate a new generation of liberal pundits.

Brock’s highest-profile move came this past fall, when, after the midterm elections in which conservative independent-expenditure (I.E.) groups like American Crossroads spent close to $200 million to help Republicans take back the House, he announced that he was forming an I.E. of his own. It would be called American Bridge, and he promised that it would flood the airwaves on behalf of Obama and other Democrats in 2012. In an interview with the New York Times, he boasted of his fund-raising record with Media Matters and predicted even greater success for American Bridge: “My donor base already constitutes the major individual players who have historically given hundreds of millions of dollars to these types of efforts. They just need to be asked, and I have no doubt they will step up at this critical time.” According to people familiar with Brock’s thinking, he wanted American Bridge to be the liberal analog to American Crossroads—which would make Brock the liberal analog to Karl Rove.

“The tortured gay intellectual who wrestled with his soul—man, is it a good show.”

But Brock quickly ran into problems. For one thing, although Obama’s campaign team had indicated that it wanted an I.E. group to help with his reelection, that didn’t mean it wanted Brock leading it. Some Obama people continue to harbor ill will toward Brock owing to his behavior in the 2008 Democratic primaries, when he seemingly turned Media Matters into an adjunct of Hillary Clinton’s campaign. “If you think about his psychology, it’s all wrapped up in the revival of the Clintons, because they embraced him when he turned away from the right,” complains one Obama ally. There was also concern that Brock’s hyperpartisanship might not be such a good fit for a president who still strives to be post-partisan.

But more than any animosity or doubts, there’s the simple fact that the insular and controlling team around Obama simply doesn’t know Brock. When I asked one Democratic strategist who’s close to the White House about Brock’s relationship with Obama’s team, he replied, “I don’t think he has one. I’m not saying it’s negative; it just doesn’t exist.” Another Democratic strategist asks, “Do you think David Plouffe and David Axelrod are going to let David Brock go out and build an empire to explain Barack Obama’s policies and worldview to voters?”

Still, Brock seemed to believe there was one surefire way to overcome the White House’s objections—or at least force its hand: by raising so much money that Obama’s team had no choice but to let American Bridge become, as one liberal activist puts it, “the ‘It’ I.E.” of 2012. But when Brock went to his donor base and asked, it did not step up. For the first time in his fund-raising career, Brock didn’t have the magic touch. Peter Lewis, for instance, hasn’t given any money. “There are certain things that interest me and certain things that don’t,” he says. “These kind of groups can be a bonanza for ad agencies and political consultants and other horseshit.” In the end, Brock was forced to dramatically scale back his plans for American Bridge (it’s been resized to be smaller than Media Matters) and reduce its role to performing opposition research for other Democratic-leaning I.E. groups.

Brock’s failure to turn American Bridge into a political behemoth is in some ways attributable to his success with Media Matters. Many of his supporters believe so strongly in the mission of Media Matters that they don’t want Brock giving it anything less than his full attention. But their reluctance to embrace Brock’s newest endeavor also reveals something about how they conceive of him. Brock has long viewed David Horowitz as a cautionary tale—an apostate who, because he is constantly fighting old battles with his old self, has become an increasingly marginal figure. And yet, despite all his efforts to play the inside game, Brock still finds himself coming up against his past: a right-wing hit man who defected to the other side. “You know that saying the Obama people have, ‘Know your lane’?” says one progressive activist who’s friendly with Brock. “Everyone who has supported him knows his lane. They’re not going to embrace his moving to another lane.”

Though he tries very hard to conceal his frustration, Brock has clearly reached the point where he wants to be taken on his own terms. “I hear that people feel that I’m somehow still trying to assuage sins of the past, or that this is some form of penance,” he says the first time we meet. “I think that came with publication of Blinded by the Right. I made the apologies that needed to be made, and so I didn’t feel that Media Matters was a continuing form of saying I was sorry.”

Perhaps the simplest way that Brock could widen his lane on the left would be to impress his fellow liberals not with his indisputable strategic cunning but instead with a frank articulation of his core political beliefs. After all, Rove did not get to where he is today simply by attacking liberals; he also offered an argument about what conservatives should stand for. But despite the fact that Brock has now spent a decade firmly ensconced on the left, he remains uncomfortable talking about the political issues that define it. “I have never had a serious conversation with him about policy or public philosophy,” says one prominent Democrat. “I have absolutely no clue what his ideological moorings are. I don’t offer it as a critique of the guy, but I just literally don’t know.”

If there is a single thread that runs through Brock’s strange ideological journey, it is personal, heated antagonism. He became a conservative as a college student at Berkeley because he was appalled by political correctness. His jolt to the left was motivated by disgust, and even now, his liberalism is largely a form of anti-conservatism. His remains a politics of pique.

On a recent afternoon at Media Matters’ headquarters, I try to draw out Brock on what he is actually for. “A lot of what I think about is tolerance in the debate and trying to tamp down on the toxicity of it all,” he says after a long pause. “So, if you’re asking me why am I a progressive, those are kind of the ways that I think about it. But I also think of it frequently in opposition to what the right is doing.” The day before, he had given a pep talk at a Progressive Talent Initiative boot camp, urging the liberal-pundits-in-training to carry forth the progressive message on the airwaves. But now, as he sits on a couch and struggles to define his own beliefs, it’s clear that Brock himself is agnostic about what that message is. “I’m comfortable on the progressive side,” he continues. “But I’m still more pitched at fighting the right than I am about building a progressive platform for the future. It’s fair to say that that conversation doesn’t interest me as much.”

See Also:

The Fox Campaign Pt. I:

The Circus Roger Ailes Created