In the middle of April, Matthew Marks, the world’s most precocious art dealer, trekked to the American interior to honor a triumvirate of premier clients—Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, and the sculptor Robert Gober—at Minneapolis’s Walker Art Center. The museum was dedicating rooms to each of them in its new wing. Only Kelly and Gober were in attendance for the weekend-long rounds of dinners and ceremonies. Nevertheless, Jasper Johns, still tucked away in his northwestern-Connecticut home, loomed over the proceedings in a typically outsize way. That’s because Marks is poised to preside over one of the biggest events of the spring art season: On May 7, he will host Johns’s first exhibit of new work in New York since his 1996 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, showing some 40 new paintings.

Landing Johns is a monumental achievement for Marks, who is a boyish-looking 42 years old. True, his eponymous gallery represents an enviable list of talent—Brice Marden, Andreas Gursky, Nan Goldin, Katharina Fritsch, Roni Horn, and Terry Winters—and he has held exhibits of work by Willem de Kooning, Lucian Freud, and Cy Twombly. But a Johns show is an event of the sort rarely seen in today’s art world. Johns is America’s—some would say the world’s—preeminent living painter, not to mention the most highly priced. One Johns canvas, False Start, netted $17 million in 1988, which is believed to be the record price for a work by an artist alive today.

Since 1957, Johns had sold his work through Leo Castelli, the famous Upper East Side gallerist who, with Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, Roy Lichtenstein, Donald Judd, Claes Oldenburg, Richard Serra, Dan Flavin, Andy Warhol, Robert Morris, and Cy Twombly on his roster, became a cultural icon in his own right.

“Jasper’s relationship with Castelli is very impressive,” Marks says. “He was with him for 40 years. It’s inconceivable to me that anybody could be that loyal. When I was growing up, that was my model of the great gallery. I remember as a teenager going up there to see Jasper’s new work, discussing it with my friends.” When Castelli died in 1999, every other prestige gallerist was eager for a shot at debuting Johns’s remarkable new works, what Johns calls his “catenary series.”

Some curators and collectors venture that in Marks, Johns may have seen a glimmer of the old Castelli. Johns himself didn’t want to compare the two: “Leo was a great friend for a long period of time,” he says. “It was a history of growth for both of us.”

But Johns, after going nearly a decade without a major new exhibition, might well be thinking that a Marks show could augur more growth. Had Johns decided to show with, say, Knoedler, it would have been akin to being embalmed. Pace, for its part, is too corporate and sanitized in its sensibility for an artist like Johns. And Larry Gagosian, despite his sharklike business instincts, has struggled to bring longevity or vibrancy to the work of already established artists who came to him well into their careers (David Salle and Francesco Clemente come to mind). Johns doesn’t need Marks; he could have gotten somebody to start a new gallery just to show his work. But, as his paintings attest, Johns is a meticulous man of deliberate calculation, and it’s unlikely he made the move to Matthew Marks haphazardly.

Johns, who is 74 years old, completed the catenary series between 1997 and 2003, by which point he and Marks were well into their courtship. “I basically wrote him a letter one day, probably seven or eight years ago, and asked if I could come to his studio sometime,” Marks recalls. When Johns agreed, Marks went up to Connecticut to find the studio “filled with these amazing paintings. I could tell at some point that this was the beginning of a series. Two finished paintings and another one that was almost finished. That’s a lot of paintings to see in Jasper’s studio.”

The new works play with catenary shapes—the curve formed when a cable is hung between two points, as on the sides of suspension bridges—to produce a spare, layered image. An untitled painting, and the only white picture in the series, has a very active surface, with a large catenary draped from wood strips at the canvas’s far edges. Others reference his personal history and earlier works: an image of his grandparents, handkerchiefs, harlequin patterns, and a dragon-printed “Chinaman” costume from his childhood.

Marks kept asking if he could exhibit Johns’s work. “I said it so many times that I gave up. I mean, you don’t want to be a pill.” Eventually, Johns agreed to show some of the works in a small traveling museum exhibit brokered by Marks. The show went to San Francisco, Dallas, and New Haven. “He was very generous with me,” Marks says. “And then, after Leo Castelli died, he began letting me sell the pictures.”

Marks quickly sold the catenary paintings for between $2 million and $4 million per work, depending on the work’s size. (Save for a lone picture that the artist is keeping for himself, all the pieces in the pending exhibit have been sold.)

In January 2004, when Marks brought some curators from the Art Institute of Chicago down to St. Maarten, where Johns spends his winters, to sell one to them, Johns declared that the canvas was the last one in the series. “At that point, he said he was willing to show them,” Marks says.

“Matthew seemed to think it was a pity that they were being sold without the public having the opportunity to see them,” Johns says. The works were either being shipped straight to collectors or coming into the gallery briefly and being shipped off. This appeal to artistic vanity is typical of how Marks conceives of his work as a gallerist: He is conspicuously slavish in his devotion to his artists.

“Artists have strange and specific needs that have to be fortified,” Johns says. “They like to think that they are the center of attention. And Matthew”—he laughs to signal what an understatement this is—“I think Matthew is capable of making artists feel that.”

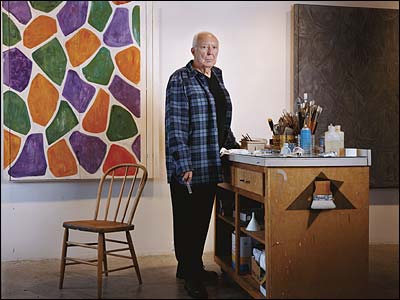

Jasper Johns in his Connecticut studio.Photograph by Jeff Riedel

Not all gallerists share this knack. Tony Shafrazi, for example, used to visit the painter Philip Smith in his studio, and, if he wasn’t impressed with what his client was doing, take a paintbrush to Smith’s works-in-progress, to demonstrate how to improve them. Donald Baechler, who remains close to Shafrazi and is happy to work with him, recalls, “Tony used to call my studio and give me advice on how to paint. I’d put the phone down and keep painting, and when I picked it up fifteen minutes later, he’d still be talking.”

Marks’s extremely user-friendly approach to representing artists also serves as a useful recruitment tactic. “I don’t discover artists,” Marks says. “Almost all of my artists showed with somebody else before they came to me. So, obviously, they left because, wherever they were, that place was not doing what they were supposed to do. I spend a large part of my day on the phone with them from home just making sure they’re taken care of. I talked to Robert Gober today. I talked to Ellsworth. I should’ve talked to Brice, but I haven’t yet, so I’ll call him this afternoon.

“I will always take an artist’s call if I am on the phone with a collector,” Marks says. “And I will never take a collector’s call if I’m on the phone with an artist.”

“Artists like to think they are the center of attention. And Matthew”—Johns laughs—“is capable of making artists feel that.”

Marks’s clients are quick to return the affection. “Besides being my dealer, Matthew also became a sort of financial adviser to me,” says Marden, who has been represented by Mary Boone and by Pace, and was shown once by Gagosian. “I always needed a dealer who could pay me in advance, and then I paid it back out of future sales. Basically, Mary was just very happy if you owed her money. With Matthew, it is a little bit different. It’s more his goal to get you out of the situation. I could see the light at the end of the tunnel.” And while Marden’s always been fond of Gagosian, he says, “With Larry, I always got the feeling he was most interested in pursuing me. I wasn’t sure how he’d be on the follow-through.”

Such household names as Marden and Kelly had their places secured in the pantheon long before Marks came into their lives, but there are plenty of younger artists whose careers took off when they began working with him. Andreas Gursky’s large-scale photographs, gorgeous though they are, were once considered the stuff of postcards, though in the late nineties he broke records for prices fetched at auction for photography. Nan Goldin was an underground phenomenon before Marks began representing her. “Matthew just allowed her to really get her work together and get it out there,” Marden says. “I didn’t think Nan was being well represented. You can deal with her as an artist or as someone who’s producing product and commodity, and Matthew understood that she was an artist.”

Marks spent hundreds of thousands of dollars (“I’m not even sure how much; I don’t like to think about stuff like this”) on a 2000 installation by a young English artist, Darren Almond, who built “the world’s largest digital clock” out of a 40-foot-long shipping container. Almond photographed the piece as it was transported via barge across the Atlantic into Newark Harbor. Marks funded the project on faith. Almond’s drawings and photographs sell in the range of $7,500 to $15,000, and it will be a long time before Marks earns back his investment on him.

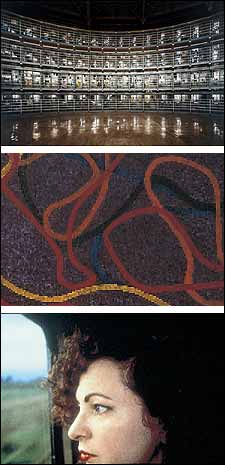

Andreas Gursky

Stateville, sold to private collector, May 2004. Brice Marden

Red Rocks (1), sold to private collector, May 2002.

Nan Goldin

Self-Portrait on Train, Germany, sold to Tate Modern, London, July 1997.

It was pouring in Minneapolis, and at 9 A.M. sharp, Marks and his boyfriend, Jack Bankowsky, set out to tour the circuit of open houses that Minnesota’s biggest art collectors were hosting at the Walker’s behest. These outings serve a dual purpose for Marks: They are a sort of sales trip, in which he gets to play the influential Manhattan gallerist before status-conscious heartland collectors for the sake of drumming up business. But they are also field trips into midwestern domesticity for Marks and Bankowsky, who greet each destination with a heavy dose of irony. Marks hired a Town Car for the occasion, and it deposited the two of them first at the home of Ralph and Peggy Burnet, they of the enormous home-sales empire.

The house, in the suburb of Wayzata, is a series of white geometric shapes stacked on top of one another and relieved by rows of enormous plate-glass windows. “That’s a big, nice house,” Marks said. “I mean, I don’t want to live there, but it’s grand.”

“I’m looking forward to seeing some art and some real estate today,” said Bankowsky, who teaches in the art program at Yale and was formerly the editor-in-chief of Artforum magazine.

Marks and Bankowsky ran between the raindrops from the car into the Burnets’ open garage door, beside the couple’s Maserati and Mercedes sedan. They entered the house through the mudroom.

“Hellooooohhhhh,” a woman’s voice called out. “Hi,” Marks mumbled, most certainly inaudibly to Peggy Burnet, who materialized shortly.

“Oh, hey, you guys,” Burnet said. She was blonde and sporty-looking and appeared far too young to have five grandchildren. She had on a green-and-pink tweed Chanel jacket. “I thought, Who’s coming in through the garage? How gross. But it’s you fellas.”

Marks and Bankowsky said nothing, until Burnet invited them to join the party. “Okay,” Marks said sheepishly, looking at his boyfriend as if the two of them were being dragged to the winner’s circle at a NASCAR rally.

To call Matthew Marks awkward would be a bit like calling Bill Clinton ambitious—and as with Clinton’s primal ambition, Marks’s social diffidence can be both a strength and a weakness. Marks is tall, about six-one, but stoops so self-consciously in public situations that at first he appears to be bowing in a gesture of mock formality. And although he is fit, thanks to constant dieting and time at the gym, he was overweight into his twenties, and that seems to have left him partial to generous, black, smocklike clothes—this goes for both jackets and shirts. Marks has a high hairline and a circle of curly locks behind it that puts one in mind of the paper frills on a crown roast. His only concession to a normal human level of interest in his appearance are his eyeglasses, which are black and perfectly round in an anachronistically modish way, in the manner of Harold Lloyd.

When Marks speaks, his tendency to self-edit is so overwhelming that he often ends up expressing himself in virtual pantomime: rolling his open hands at the wrists and making pain-stricken faces. You’re especially apt to get anguished expressions if you force him to talk about himself, or the role he plays in developing his artists’ careers. “I’m nothing without my artists,” he has said.

Marks and Bankowsky have been together for eleven years and live in a townhouse in the West Village. “When we met, Matthew’s gallery was just taking off, and I hadn’t been in charge at Artforum for very long,” Bankowsky, smartly dressed and more outgoing than Marks, said. “We both figured each other was a person worth knowing. Then, after we’d known each other six months, we moved in together.”

The Burnet house was chockablock with the work of major contemporary artists: Ellsworth Kelly and Gary Hume (both of whom Marks shows), and a bunch of significant pieces by Damien Hirst, including, in the living room, six skeletons in a glass case and a large canvas of multicolored dots arrayed in rows against a white background.

Upstairs, outside the master bedroom suite, a middle-aged couple paused to admire another Hirst sculpture: thousands of bronze, hand-painted pills laid out single-file on a mirrored metal grid.

“Now, when you’re mounting it, does he specify where the pills go or not?” a woman asked Ralph Burnet, a small man with strawlike gray hair.

“Yes, he sends them in boxes, and they’re all numbered,” he said.

Downstairs in a hallway, there was a knot of people staring at an installation by Maurizio Cattelan: two tiny electronic reproductions of office-building elevator doors built into the wall at floor level. They were constantly lighting up and opening and shutting.

In the kitchen, Peggy Burnet was on the telephone. “Good morning, Ellsworth,” she said. “Yes, they are all here. I’m just delighted. Now, when are you coming by?”

She looked at Marks and mouthed the words Ellsworth … Kelly. The visitors filed out of the Burnets’ house. Most headed for the bus that had been chartered by the friends of the museum; Marks and Bankowsky got into their Town Car.

A large Richard Serra sculpture, consisting of nine black Corten-steel walls arranged in neat order, came into view in the Burnets’ backyard. It was a reminder of why the Burnets were important to Marks, who sold it to them four years ago. His deferential and withdrawn demeanor has pointed up his awareness that he’s been in the home of potential big art buyers, but his typically soft-sell manner has kept him from overplaying his role as a sales broker.

This was the first time Marks had seen the Serra sculpture at its current home. Standing in silhouette against the flat prairie where Wayzata has sprouted, the Serra walls looked a bit lost and forlorn, not unlike the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. “Look at that,” Marks said. “It’s just … on the lawn. It looks smaller when it’s outside, I guess.”

The center of New York’s art world, the modern-day version of what Tom Wolfe once called “the Art Gildo Midway,” used to be up on 57th Street. In the seventies and eighties it migrated to Soho, and for ten years now it has occupied a few square blocks in Chelsea—21st through 26th streets on the block between Tenth and Eleventh avenues. And this western migration happened mainly because Marks had the bright idea of moving his uptown gallery there before anybody else did, and then everybody followed him. Marks’s primary gallery is on 24th Street, but he also has a grand space on 22nd with vaulted ceilings and eight dramatic skylights, and a tiny one-room gallery on 21st.

Along with three other gallerists, Paul Morris, Pat Hearn, and Colin de Land, Marks started the Armory Show, which has become the preeminent art fair in the country. “Basically it’s grown into a big pain in the ass,” he says.

At their townhouse, Marks and Ban-kowsky entertain often—large catered affairs, usually. It is common for Marks’s artists to show up, but he rarely invites collectors; it’s not merely out in the Big Ten states where Marks can be seen keeping collectors at a certain haughty remove. “In all the dinners of theirs that we’ve been to, I can only recall once, after an opening of Terry Winters’s, I believe, that suddenly there were all these awful strangers, who turned out to be collectors,” art historian Robert Rosenblum says. “I just don’t think he has much taste for the sort of person who collects art. Although he’s a great gossip and he’s very good at imitating those silly people and the way they talk, or what silly thing [MoMA president emerita] Aggie Gund was wearing when he last saw her. She’s a terrible dresser, and Matthew and Jack love to talk about it.”

As with all rites of social derision, there could well be a good deal of self-recognition here, for Marks was, in fact, a teenage art collector. He grew up near the Columbia campus and went to St. Bernard’s for elementary school, then to Dalton. His father, Dr. Paul Marks, is a cancer specialist who between 1980 and 1999 was the head of the Sloan-Kettering hospital; his mother is also a doctor and taught genetics at Sarah Lawrence.

“I was one of, I think, three Jewish boys at St. Bernard’s, and the only kid who lived uptown from the school,” he says. “It was on 98th and Fifth, and at the end of every day, the school insisted on having an adult escort me to the crosstown bus stop and wait with me.”

Marks began collecting art when he turned 13. “I didn’t have a bar mitzvah, but as something like a bar mitzvah present, I asked for a painting,” he recalls. “I had a book of American art and I somehow got it in my head that I wanted to own a painting by every artist in it.” Having seen a movie on Channel 13 about Georgia O’Keeffe, he decided to begin with her, and one Saturday his father and he walked to a gallery that sold her work. “It became clear that owning an O’Keeffe painting was not meant to be, but somebody at the gallery said a drawing might be nice,” he says. “Then, that was too expensive. If you turned the page in the book, the next artist was Arthur Dove. I tried to buy a print of his, but there weren’t any. The next page was Marsden Hartley, and a gallery sold his prints, and I picked out a mountain scene that cost $125. I had to beg for it for a while, but it was fantastic. I still have it in my house.”

Through high school, Marks continued to buy and trade for prints. He went to Columbia for two years and worked as a paid apprentice at the Pace Gallery. “I remember him coming to visit me and look at some art when he was a teenager,” says Timothy Baum, a private dealer who specializes in Dada and Surrealism. “I had an obscure, hand-colored print that interested him. I was amazed by his astuteness and his enthusiasm for it. It wasn’t worth much more than a few hundred dollars. He had to pursue me until I’d receive him.”

Even after he transferred to Bennington for the last two years of college, Marks continued to work at Pace during vacations. “Bennington is an odd place, because if you’re interested in literature, you don’t just read it, you have to major in writing,” he says. (Bret Easton Ellis, Donna Tartt, and Jonathan Lethem were among his contemporaries.) “So they wouldn’t just let me study art, I had to be an artist. I painted for two years, and it was useful as far as learning what artists go through, but as soon as I graduated, I packed up my pictures and brought them straight to my parents’ attic, and they’ve never come out since.”

Toward the end of his senior year, he told a member of the art department that he planned to become an art dealer. The instructor, he says, looked him in the eye and told him not to get his hopes up: “He said, ‘They’ll eat you alive.’”

For three years, Marks went to London, where he was employed by Anthony D’Offay, a major dealer of contemporary art. D’Offay is an elegant but odd man with a habit of touching people on the hip to imply confidentiality in conversation—a level of forced intimacy worlds away from Marks’s retiring manner. But D’Offay mentored Marks in building a dealership geared primarily to the needs of artists—and just as important, D’Offay was the person who introduced Marks to Jasper Johns.

Matthew Marks’s Top Ten

Name artists and the gallerist who loves them.Gary Hume

since 1991 Brice Marden

since 1991 Ellsworth Kelly

since 1992 Roni Horn

since 1992 Nan Goldin

since 1993 Andreas Gursky

since 1996 Terry Winters

since 1996 Sam Taylor-Wood

since 2000 Robert Gober

since 2002 Jasper Johns

since 2005

In 1987, when he was 24, Marks organized an exhibit of British Modernist art, and he and D’Offay brought it to a gallery in New York for a month. One day, Jasper Johns walked in and wanted to buy a Gaudier-Breszka drawing of Ezra Pound and then, after having a longer look around, several other pieces. Marks had the idea that it would be better for D’Offay to offer them to Johns in a trade rather than merely charging Johns money. “The end result was that we went to visit Jasper—it was when he was still on 64th Street—and he let Anthony pick out a drawing,” Marks says. “He offered Anthony a handful of works. They were all wonderful. We chose a beautiful watercolor.”

By the time Marks decided to move back to New York and, in 1989, try to open a gallery of his own, his art-world apprenticeship had given him the first prerequisite for the job: a tremendous Rolodex. To afford the $6,000-a-month rent for a 1,000-square-foot space on upper Madison Avenue, he began selling off some of the artworks he’d bought as a teenager. “There were quite a few things that had turned out to be very good investments, like things I bought for $700 several years earlier that were now worth $20,000, easily,” he says. “At the time, everything was going up exponentially by the minute. There were a number of things I subsequently bought back for considerably less.” It also didn’t hurt that his father was head of Sloan-Kettering, which gave him ready access to a lot of rich people who were patrons of the arts. His mother’s best friend, for instance, is Barbara Walters.

Marks discounts the role these family ties played in firming up his business. “Not that many of their friends are that serious about art that they were going to buy things from me,” he says. “What my parents had on the wall was nothing good. The one decent thing they had was a Picasso etching from the Vollard Suite. I kind of got rid of everything else. Now I’ve filled their house with art. Now they have beautiful things by the artists I show.”

The open-house tour moved into Minneapolis proper—a collector’s home in Kenwood, the stately neighborhood where Mary Richards, of The Mary Tyler Moore Show fame, lived. The owners were delighted to see Marks, and they warmly recalled once visiting his gallery, but he didn’t remember them. “I guess they bought stuff from me, I don’t know. It must’ve been those six Cy Twombly photographs on the landing.”

“It was nice to see a house with real furniture,” Bankowsky said. After visiting one house earlier in the day, he’d asked if anybody thought it had been decorated by the same people who did all the Radissons.

Back in the Town Car, Bankowsky and Marks discussed the day’s first celebrity sighting. “Did you see Dr. Spock?” Marks asked. “The guy who played him on Star Trek, he was there.”

Mister Spock, he was corrected. Bankowsky noted that Leonard Nimoy is an enthusiast for contemporary art. “He’s supposed to be, like, a really elegant older man.”

Marks gave this some thought. “If you’re talking about for an L.A. collector, maybe.” Late in the afternoon, after Marks and Bankowsky had returned to their hotel to get ready for the dinner at the Walker, they stopped off at the home of Judy Dayton. The collection that she amassed with her late husband, Kenneth Dayton, is the best in town. Kenneth came from the family that founded Dayton’s, an enormous midwestern department-store empire—now the Target Corporation.

Bankowsky recalled that there had once been a person named Dayton who worked at Artforum. “I think she was from somewhere out here,” he said. “She must be related.”

“They’re all related,” Marks suggested.

“She has to be,” Bankowsky said. “Because the entire time she worked at the magazine, she didn’t cash a single paycheck. After she left, somebody opened her desk drawer, and there were all the paychecks stacked up.” He indicated an inch or so worth of checks with his thumb and forefinger.

Judy Dayton was in her backyard, showing Ellsworth Kelly where she had installed his aluminum three-piece abstract sculpture, off to the side of the lawn amid evenly planted rows of locust trees. Down a short slope is a Claes Oldenburg banana built of yellow metal. She was wearing a necklace of enormous pearls that played off her winter tan.

“Hey there, fellas,” she said when she saw Marks and Bankowsky.

She went inside and returned with a tray of champagne glasses. Marks asked for ice water, and when everybody was seated around a patio table, he proposed a toast.

“To Ellsworth,” he said.

“To Ellsworth,” Mrs. Dayton promptly echoed.

Kelly, a spry and impish man in his eighties, took a sip of his champagne. “Mmmm. I’m very thirsty,” he said. “Look at these gentlemen in ties. Matthew, you’re wearing a tie.”

“I own a tie,” Marks replied.

Kelly has been one of his artists almost since the Matthew Marks Gallery was launched, in the fall of 1991. Marks’s first show was an exhibit of artists’ sketchbooks, which he’d procured simply by writing to every artist whose work he liked.

Almost everybody he contacted—including Johns, Kelly, Marden, Freud, Robert Ryman, Julian Schnabel, Andy Warhol, and Gerhard Richter—was happy to let him show their old doodlings and rough sketches. “Louise Bourgeois”—whose name Marks pronounces boo-geois—“didn’t say yes, she just sent an assistant over with a sketchbook right away,” he said.

“That was a real moment,” Kelly recalled. “The notebooks were all in glass cases. And a lot of the artists came in and wanted to see my sketchbook. It was a 1950 sketchbook.”

“It was fantastic,” Marks said.

“Richard Serra, he wanted to see the sketchbook,” Kelly said. “Matthew told me he wanted to see all 60 pages.”

“It was Cy, actually—he wanted to see everything.”

Marks did not put any of the sketchbooks up for sale. In asking to exhibit the artists’ work, he made no demands on their ongoing relationships with their respective dealers, and a handful of them eventually decided to have him represent and sell them on a full-time basis. It was an astute marketing strategy for a fledgling gallerist—but more than that, it was an idea that only somebody in love with the process of how artists make art could have thought up.

A more recent such labor of love from Marks is A Robert Gober Lexicon, a detailed paperback book he commissioned to accompany his recent Gober installation on 22nd Street. Two years in the making, the book, by Brenda Richardson, intricately translates and explains the influences of what many would consider a difficult roomful of sculpture, complete with diaper packages, a torso giving birth to an adult’s leg, and a headless figure on a cross spouting water from its nipples. This is, one has to admit, a far cry from the Damien Hirst T-shirts that Gagosian is currently selling at his gallery two blocks away.

As the Minneapolis junket made clear, Marks’s genius is his recognition that artists are ultimately more important than collectors. The informal business model of the Marks gallery is that where artists will go, collectors will follow, and this is what has positioned him as a successor to Leo Castelli. “He’s really interested in finding the best home for a picture,” Terry Winters says. “There have been cases where he’s held a painting rather than sell it because he thought the buyer was looking to turn around and sell it for a profit somewhere down the road.” Marks prefers to sell to museums, or to collectors who he knows will eventually donate the works to a museum. “Museums are where I want my artists’ work to be going,” he says.