I always knew the gorilla had a secret. For the better part of 50 years, first with my parents, then with Cub Scouts, sixth-grade classes, and girlfriends, some of whom understood and some of whom didn’t, I came to see the gorilla, frozen in mid–chest beat in his glass case at the Akeley Hall of African Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History. So much like us, yet not us, the secret was in the silverback’s eyes, tender and knowing, harboring some vast, hidden narrative of hurt. I always wanted the gorilla to tell me his story, but how could he, stuck inside a diorama on Central Park West for the past 70 years? But things change. Secrets are revealed, or at least versions of them. Such was the case a few days ago when I visited the gorilla along with the artist Walton Ford.

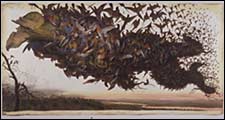

Walton (as everyone calls him), who grew up a bit nerdy in the Hudson Valley capturing black snakes in his mother’s pillow cases and surreptitiously stashing them in his closet, and who this month will display his most recent flock of fabulously ornate, exquisitely precise, wildly idiosyncratic watercolors depicting the state of the natural world at the Paul Kasmin Gallery, has also spent a lifetime visiting the gorilla. Years ago, before he began painting his often ironic, often hair-raising menagerie of possessed black leopards stalked by ignorant villagers, stumbling quaggas with giant dangling dicks, peacocks with their tails on fire, and tree branches breaking under the weight of so many soon-to-be-extinct passenger pigeons that, as he puts it, “the fecundity is almost disgusting,” Walton, now 42, made ends meet as a wood refinisher at some of the classier uptown apartment houses, including the Dakota. It was cool to work in the same building where John Lennon both lived and died. But for Walton, the best part was the proximity to his beloved museum, where he went, in his typically obsessive fashion, every lunch hour. It was then that the artist learned the gorilla’s secret.

“Well, he’s dead,” Walton says as we stand in front of the mutually admired simian. “People don’t get that. These animals are dead. That they’re not just these remarkably lifelike likenesses. They’re dead, as in they used to be alive until they were killed.”

With that, Walton, who rarely needs an invitation to do all the talking – “If I’m wearing you out, just tell me” – tells the story of Carl Akeley, who died in 1926. Explorer, hunter, conservationist, sculptor, photographer, and known as the “father of modern taxidermy,” Akeley was one of several nineteenth-century-style colonial adventurer–robber baron–gentleman naturalists such as Sir Richard Burton, who had 40 monkeys sit at his dinner table so he might learn their language, and John Audubon, with whom Walton Ford maintains an undying love-hate relationship.

“Akeley was the museum’s great white hunter,” Walton relates. “His safari expeditions brought in most of these animals. His taxidermy technique was revolutionary. Before, they’d just stuff the animals like pillows. But Akeley was a genius. He’d shoot the animals and skin them. Then he’d incorporate their skeletons into these perfect sculptures. With the skin back on, they really looked alive. He’s the inventor of these dioramas, which are the most beautiful in the world. Nothing comes close. The vegetation and lighting is great, just great. You will not find any landscape painting in New York better than these backgrounds.

“Somewhere along the line, Akeley decided to become a conservationist. He started the first gorilla preserve in the world in the Virunga range near Rwanda. Except when he went back, he got dysentery and died. How good is that? I mean, there’s this famous picture of him with a leopard he killed with his bare hands. Then he decides he wants to be a good nonviolent guy, returns to the scene of the crime so to speak, and dies of the shits.

“He was buried in the same area as this gorilla diorama. Years later, Dian Fossey found Akeley’s grave, and it had been robbed. It had been dug up. Human bones were around.”

These are the sort of stories Walton likes, the kind that inform the often sly environmental passion plays at work in his pictures. Indeed, in the 1998 watercolor Sanctuary, which is included in the new book of his work, Tigers of Wrath, Horses of Instruction (Harry N. Abrams), there is our old friend the silverback, liberated at last from his glassed-in tomb. His face impassive, eyes not quite so melancholy, the gorilla perches on a sinuous branch, cradling a human skull, a skull which in the Walton Ford version once belonged to Carl Akeley.

“You know,” the painter says, gleefully delivering the punch line. “It’s like, he collected them, and they collected him.”

Amid Ford’s lush kill-and-be-killed channeling of natural selection, the story of Akeley’s gorilla rates pretty much as a happy ending. Bleaker scenarios abound, black comedy aspects notwithstanding. In Walton’s world, all tempting fruits are attached to unseen snares, tigers are bedeviled by bees, and great auks march like lemmings into flames, never knowing (or maybe they do) that they are about to be hunted into oblivion. But this doesn’t mean that Walton Ford would be happy to be taken as a PETA member, or a snooty George Page–narrated World Wildlife Fund moralist.

“No, man,” he says when asked if he is a vegetarian. “If it flies, it dies. I’m not a Ted Nugent red-meat guy, but I’m in there chomping.” More interested in “the representation” of animals than in the actual animals themselves (he doesn’t visit the Bronx Zoo because “they’re always sleeping – I can’t do anything with that”), Walton rates the museum as his major inspiration. But he can’t relate to the whale hanging from the ceiling.

“Blue whales are a drag. They’re big but boring,” the artist says dismissively. “What do they eat, krill? I cannot paint a krill eater. The thing doesn’t have any fucking teeth. I like things that bite. A sperm whale, Moby-Dick, that’s my kind of subject. A bad-ass.”

Such bravado aside, Ford, who will happily rail against the global economy and cultural imperialism (one of his best Animal Farm allegory pictures, N.G.O. Wallahs, inspired by a six-month trip to India, shows a European starling handing out Hershey kisses to the local aviary while a carrion-eating marabou stork looks on in horror and disgust), thinks current environmental concerns, while unavoidable, are wrecking places like the Museum of Natural History.

“These kinds of museums are really nineteenth-century trophy rooms, displays of conquest. You know, this is what your tax dollars have brought back, the Rosetta Stone and these gorillas. You can’t have that now, it’s too horrible. But these new plastic biodiversity exhibits, there’s no drama in them. They run counter to the idea on which the museum was founded.”

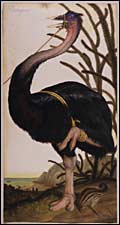

Today, though, the museum is a side trip for Walton, who really came to town to deliver his elephant-bird painting for his Kasmin Gallery show. The largest single bird ever to walk the earth, the Aepyornis maximus, or elephant bird, a flightless native of Madagascar, was thought to have stood at least ten feet tall, weighed more than 1,000 pounds, and been capable of producing an egg containing two gallons of liquid. Walton has painted his elephant bird to scale, making it a bitch to get inside his Subaru station wagon to drive down from Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where he relocated six years ago after a member of the Spin Doctors moved into his Chambers Street loft building, which Ford, more the Captain Beefheart type, figured was a death blow to the coolness of the neighborhood.

The elephant bird took Walton, who will spend a week on a lion’s mane or an elephant foot, three months, “pretty fast, for me.” Not that there is much chance any avian morphologist will question Walton’s deployment of the bird’s tertial feathers. Ample fossil evidence exists, but the animal is thought to have become extinct in the seventeenth century. “It is one of those things never seen by a white man,” says Walton, who doesn’t mind watching King Kong over and over again. Despite all his mania for verisimilitude, Walton is also well aware of the elasticity extinction adds to the canvas. Since the animal has rarely been pictured, his elephant bird is likely to become the elephant bird.

At the Kasmin Gallery, Walton unfurls the elephant bird, which has been rolled up like kitchen linoleum. And there it is, this massive, brown-breasted ostrich thing standing on a hillside, with the flinty diffidence of being the last of its breed. Below, on the beach, in a typical Ford addenda, pirates haul away the stolen riches of the island, never guessing they are being watched by such fabulous booty.

It is a stunning picture, and Paul Kasmin, a seemingly unflappable Britisher who first began drumming up the Walton Ford market five years ago, is enthused. Ford, however, seems a little troubled. Walton loves the bird – mad-scientist-style, he loves all of his creatures – but he thinks something is missing. Then it comes to him. “You know, it is one of the great bummers of natural selection that birds evolved to have no penises … Imagine the one I could have stuck on this guy.”

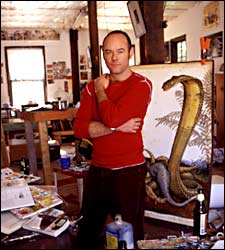

“I’ve always had this sick turn of mind, in parts,” Walton Ford says a few days later, sitting in his remarkably messy but suitably rustic studio on the second floor of an old lumberyard building on the other side of the railroad tracks from most of Great Barrington’s prim little downtown. Picking through piles of Doritos wrappers, empty Poland Spring bottles, ripped Elvis Costello posters, and stacks of books like A Sporting Chance (techniques for hunting mountain lions with a crossbow are illustrated, along with several man-catching schemes), Walton has managed to locate several slides of his early work. “I drew animals from age, like, 3, but after I got out of school I did this,” Walton says, examining an image of a young boy tied up in a chair, duct tape over his mouth, with several older, nasty-looking children (one of whom is Walton) looking on, the sort of foul Grant Wood cartoon riff that might have appeared on an early Alice Cooper album cover. “There were a lot of bullying pictures then. I was trying to get at what a bad kid I was. Why I flunked out everywhere. Nobody liked these pictures. When I showed them – they were the first things I showed – someone wrote in magic marker on the wall BAD START. I don’t even know why I keep them around, except to remind me I’ve always had this business about captivity and control.”

This is something that Walton, ever the compulsive space cadet (ask him why he holds his pencil with four crabbed fingers and he says, “Yeah, who knows what’s up with that?”), allows he comes by “honestly.” Even though he was born in Larchmont and grew up in Croton, the son of a Time-Life executive and a doting mom, both sides of his family are from the Deep South: “They go way back. They both owned slaves.” With this, Walton picks out one of his old pictures, of a very scary old woman with wild, demanding eyes. “This is one of my great-great-great-grandmothers. Emily Donaldson Walton. On her plantation, a slave girl was born with six fingers on each hand. She wrote about it in her diary, which I found. She said: ‘My mother cut off the extra fingers and buried them under the rose bush in her flower garden. The girl was given to me and I named her Queen Victoria, which I thought was a beautiful name for my little pickaninny.’ ” Walton was “kind of blown away” by this and made a wood-cutlike print called Six Fingers depicting the scene, which he printed up and glued to “every lamppost in downtown New York … I don’t even know why, except that I wasn’t getting anywhere in the art world and maybe I needed to expose this fucked-up thing in my family.”

Things are, of course, different now, and Walton is rushing to finish two new pictures for his show at the Kasmin Gallery. One is of a golden eagle, inspired by a section in John Audubon’s painting of the creature in A Synopsis of the Birds of North America. The canvas is empty now save for some line drawing and the spotty “foxing” Ford often uses to give his paintings the look of aged nineteenth-century field sketches. The idea, however, has been there for years, since Walton first read Audubon’s Ornithological Biography. “Audubon as some Thoreau-like Johnny Appleseed of birds is really nuts,” Walton says of his sometime bête noire. “He was a mean-spirited liar. He made enemies wherever he went. He was repulsed by Native Americans. He shot more birds than he ever painted … a total dick and not even that good an artist. Yet his work became the standard for how nature is shown. I try to address this dialectic.”

With this, Walton reads aloud from the section in Audubon’s diary dealing with the golden eagle. First, Audubon describes the attempt to snare the bird with a fox trap, but the eagle managed to get away, flying more than a mile with the trap on its leg. When the naturalist got hold of the bird, the problem of how to kill it remained. He thought of ” ‘suffocating him by means of burning charcoal, of killing him by electricity,’ ” Walton reads from Audubon’s book. Asphyxiation by burning charcoal was the choice, but after two days of ingesting the acrid smoke, the eagle refused to die. Losing patience, Audubon says, “At last I was compelled to resort to a method always used as the last expedient, and a most effectual one. I thrust a long pointed piece of steel through his heart, when my proud prisoner instantly fell dead.” Painting the eagle was difficult for Audubon. Felled by what he referred to as “a spasmodic affection,” the conservationist icon was force to take to his bed for weeks.

Pointing at the canvas, Walton says: “My picture will have the eagle trying to escape, the fox trap on its leg, this horrible burning smoke coming out of its mouth. It’ll be thinking, Like, what the fuck do I have to do to get away from this asshole? … I’ll probably call it Spasmodic Affection.” When Walton first came up to Great Barrington, he wondered if being away from New York would keep him from becoming a famous artist. But it has worked out. Paul Kasmin is selling his canvases for more money than he ever dreamed possible. Now he’s the resident art star of the town. He painted a few “porno” pictures based on Lewis and Clark’s journey through the Louisiana Territory for the chef of the best restaurant in town, so he gets free food, which is a nice perk. Reflexively friendly, Walton’s got a comment for everyone, a slap on the back.

“Can’t help it, it’s the way my dad was,” Walton says of his father, now battling cancer. “Flicky Ford, they called him. He had that thing, that southern thing. He was a great storyteller, a great drinker. It’s funny: He started as a cartoonist, at which he was only okay, but when he was at Time-Life, he used to hang out with Walt Kelly, who drew Pogo. Kelly used a lot of my father’s dialogue for the strip because he was from Chicago, so how was he supposed to know how the animals in the Okefenokee Swamp talked? My dad and mom broke up when I was 10. There was a lot of darkness, but he just sailed on top of it,” Walton says, as if this is a bullet he has to dodge.

“One lucky dude, I am,” Walton says, driving home through the mountains to his home in Southfield. He says he married his wife, Julie Jones, whom he met at RISD, because “I saw these paintings, these images of restraint, and I really liked them. Then I met the artist, and she was, like, the most beautiful girl in the whole school, so that was pretty much it… . You know, I figured I’d have this great horn-dog career, and then I saw her and there was no choice.” Married to Walton now for seventeen years, Julie Jones is still beautiful, and their two young daughters, Lillian and Camellia, ages 9 and 5, are also beautiful.

It being a beautiful early-fall day, Walton and his girls are going for a walk down the road from their lovely house to the pond. The pond is behind the old buggy-whip factory, which used to support the town and has been turned into an antiques shop. “From buggy whips to antiques,” Walton says, as if it is the way of the world. The pond, which used to contain the sludge from the whip tannery but now contains a thriving little ecosystem, is full of frogs.

“Look,” Walton yells to his daughters. “This frog caught a dragonfly. He’s gonna eat it. Let’s watch.”