The exhibitions of ancient art that pass through New York, especially those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, often have a High Church atmosphere. Scholar-monks add to the storehouse of knowledge as they preserve and illuminate the greatest expressions of earlier civilizations, and play shepherd to the art flock. (Communicants in headphones receive instruction.) The High Church aspirations are laudable, of course, but sometimes these shows have an additional element, one seductively and slyly contemporary in spirit. Certain dead civilizations haunt the imagination, becoming a modern well of fantasy, escape, and longing.

Both The Aztec Empire at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D. at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—two big shows that opened last week—present an impressive scholarly face. Each contains hundreds of works, including magnificent, recently excavated pieces, and each provides a worthwhile history lesson about a remote culture. Each also has an ecumenical air, as China and Mexico, countries deeply involved with the United States, send some of their patrimony abroad to promote “understanding.” But each also has a startling modern shadow. Especially the show at the Guggenheim, where a razzle-dazzle installation of choice objects emphasizes why the Aztecs remain a source of obsessive interest.

In Western societies, the Aztecs are a blood-red symbol of passion, the very definition of “primal” power. Their unrelenting emphasis upon war, death, religion, and human sacrifice makes our SUV culture appear wan by comparison. The Aztec priests may have torn out beating hearts with rough-hewn daggers—but at least they had hearts. The Aztecs also thrill and titillate, exciting Hollywood sensibilities. (Movies like Raiders of the Lost Ark treat most ancient cultures as a kind of Aztec-Egyptian hybrid.) And while the Aztecs themselves were fierce imperialists, visiting war and destruction upon subject populations, they are also famous victims. The Spanish assault upon the Aztecs is a presiding symbol of Western brutality and colonialism.

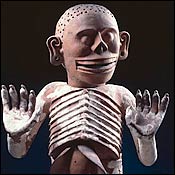

At the Guggenheim, the Mexican architect Enrique Norten has transformed Frank Lloyd Wright’s spiral into an abstract serpent. A rippling and undulating wall of dark felt conceals the bays along the museum’s ramp, providing darkened places for vitrines and creating a light-and-dark shimmer within the building. In one of the Tower galleries, which includes a large variety of pieces excavated from the Templo Mayor (Great Temple) in Mexico City, the designers have removed all ambient light, working instead with spots in a dark and shadowy atmosphere. High on one wall looms Mictlantecuhtli, a Mexican god of death who craved human blood. His skull is cavernous. His liver dangles beneath his exposed ribs.

“The unflinching Aztec faces have something urgent to impart: They meet every eye, including the modern one.”

Some will find this theatricality lurid or melodramatic. It certainly belongs to our culture, not theirs: The Aztecs would be astonished to see their work presented in this fashion. But a dull rectangular room would provide a context that’s no more accurate. Such putative neutrality is an illusion: It changes art as much as a spotlight does. Aztec art is inherently dramatic; perhaps it’s better to lend it our own theatrical devices than to lay it out like a corpse on a table. In any case, the quality of the actual objects, which have been selected by the Mexican curator Felipe Solís, could hardly be higher. In addition to clay and stone figures, the show includes ritual objects, lavish gold jewelry—the works. There are many memorable depictions of animals, among them a large stone flea, a splendid toad, a fierce rabbit, and one of the best dogs in the history of art. Serpents play an important part, of course, as do the pieces, especially knives, associated with human sacrifice. One sculpture depicts a man wearing the flayed skin of a victim.

The terrible beauty in Aztec art does not, of course, stem from grisly religious practices. In even their smallest, least important works, the Aztecs invariably seem to seek out some primal source, searching for the inner power of form; their art is never merely sweet, decorative, or pretty. Their shapes are muscular, their rhythms sinewy. Their emphasis upon death has none of the stillness of Egyptian art, but seems instead to be livelier than life itself. There’s a particular stare in Aztec art, an expression that you find again and again in the masks and figures. The figures appear startled by a sudden insight, an overwhelming sensation of something larger than themselves. Their stare suggests that moment just before death when, it’s said, the world comes into absolute focus. The unflinching Aztec faces have something urgent to impart: They meet every eye, including the modern one.

“China” has a more conventional layout than the Aztec show, and its subject does not have the same focus—inevitably, for it presents a complex period of flux. It surveys art after the collapse of the Han dynasty, when nomadic peoples swept into China and ideas crossed and crisscrossed for centuries until a powerful new synthesis developed in art, one that would flower during the Tang dynasty. Most of the work has been excavated only in the past 30 years, not incidentally the period when contemporary China began its astonishing transformation from a backward, withdrawn nation into today’s forward-looking economic power. “Dawn of a Golden Age,” in addition to its more conventional virtues, serves as a kind of metaphor. Until recently, China was falling apart, but now it dreams of coming together once more, excavating a glorious past in order to inspire its people to create an equally strong future. (Never mind that both communist and capitalist China have destroyed—deliberately or through in-difference—so much of the nation’s patrimony.)

The birth of a strong new nationalist China fascinates the world. The show at the Met, which was organized by James C.Y. Watt, calls upon an enormous range of ancient sensibilities, from the rough-hewn to the courtly, as if to remind viewers that China has always been a complete civilization—even when weakened by political divisions. Much of the art on view has the sort of burly authority we associate with ancient cultures, including that of the Guggenheim Aztecs.

Here, too, modern viewers may well feel a strange ambivalence, at once attracted by a bolder, more impassioned existence and repelled by a barbarous grandiosity. At the end of the period under review, Buddhist ideas begin to flow into China, stimulating the creation of some extraordinary early Buddhist statues. These have their own deep “stare,” one very different from that found in Aztec figures, but one in which there is also nothing weak, soft, or passive. Inner mastery and self-discipline—today celebrated in the martial-arts flicks that are so popular—is another power the present hopes to recover from the past.