In the middle of the Japan Society’s elegant bamboo garden—ordinarily a tranquil retreat—there is now a pustulant yellow globule that resembles a cross between Silly Putty and the Blob. It would like to mutate into something large enough to eat New York, I think, or at least spawn a Godzilla or two. Its maker, Noboru Tsubaki, calls it Aesthetic Pollution, and it creates a measure of anxiety in the grown-ups at the Japan Society. You don’t play Monster Mash in a Zen garden. You don’t barf near the Buddha. And you don’t kid around with Japanese history. Except that that’s not quite right: You should do such things for a moment—figuratively speaking—if you want to understand the dissonant, often bizarre psyche of contemporary Japan.

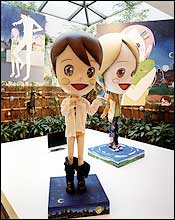

Organized by the artist Takashi Murakami, “Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture” is less a traditional exhibit of art than a work of cultural history. It focuses upon otaku, a kind of pop-cult fanaticism. On display are dozens of sappy-sweet toys, examples of anime and manga, and many depictions of monsters and adolescent cutie-pies. Works of art based upon this material are also on view, but no strong distinction is made between art and artifact. The key argument here is that, far from being just sugary kitsch, Japanese pop represents the strange, even psychotic response of a population traumatized by World War II, and then made impotent and infantilized by occupation. Fantasy can provide an escape from history. Art averts. Art anesthetizes.

From this vantage point, the firebombing of Tokyo evolved into the city stomp of Godzilla. The mushroom cloud became a pretty flower rising into the sky at the conclusion of a children’s TV show. Fantasies of power are irresistible to the impotent. Little Japanese boys (of all ages) love robots and space suits, and have a kinky obsession with girls who play peek-a-panty. Fashion and shopping provide bits of distracting and addictive glitter. Murakami calls this culture “superflat,” by which he means, in part, that the interior life of the nation has been ironed into an ahistorical and decorative field of games, melodrama, apocalypse, shopping, and cuteness. Everywhere in Japan, for example, you come upon that appallingly cute little figure called Hello Kitty. It has no mouth and no developed limbs—an image of powerlessness and, Murakami suggests, sublimated hysteria.

A great deal of imagination flows into the commercial aspects of this culture. (One wall of the exhibit is filled with remarkable anatomical diagrams of the internal organs of various monsters.) Some disaffected young people now play with the imagery in an eccentric way, much as an outsider artist might. Mahomi Kunikata, for example, has laid out a big cheery doll like a corpse and placed pieces of artificial sushi, painted with pictures of girls, upon her. An artist named “Mr.” drops the drawers of a cute little boy in a way that is slyly naïve. Chiho Aoshima makes murals that turn girlie imagery into a wild fantasia.

The title “Little Boy” is brilliant: It conflates cuteness with the nickname of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The show itself should fascinate anyone interested in an image-drowned culture, but it won’t end questions about the ultimate value of the art. There’s no reason why a great artist could not emerge from this cultural terrain. But seasoning the material with irony, or intensifying its decorative characteristics, usually results in minor work that simply comments on a social phenomenon. A major artist would have to reach in a powerful way into the sexual, emotional, and historical fear that gives rise to an impotent infantilism. But the show is utterly convincing in one important respect—this isn’t just Disney.

Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture

Curated by Takashi Murakami.

Japan Society Gallery. Through July 24.