Photography was born of the machine age, but its emotional impact is rooted in magic, fetish, and enchantment. It can stop time, restore the dead to life, and awaken distant memories. In this regard, no photographs are more miraculous than daguerreotypes, the one-of-a-kind plates that during the 1840s and 1850s became all the rage. Daguerreotypes could deliver an eerily realistic accounting of human flesh—in addition to other surfaces—but their power has often been diminished by their small size, poor condition, and awkward compositions. (They often turn into antique curiosities for modern viewers.) The exhibit now opening at the International Center of Photography, which was organized by Grant Romer of the George Eastman House and Brian Wallis of ICP, has none of the traditional drawbacks. In “Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes,” the pictures are large, luminous, and composed with an eye attuned to the light of expression as well as to the fact of flesh. This party of Bostonians from before the Civil War comes disturbingly to life. They can haunt your present.

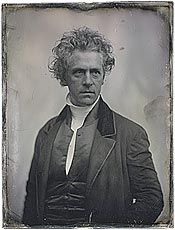

Albert Sands Southworth (1811–1894) and Josiah Johnson Hawes (1808–1901) were partners who, from 1843 to 1863, built a flourishing daguerreotype business in Boston. They made mainly portraits: Their principal customers were either Boston Brahmins or distinguished visitors passing through town. Children in party dresses, abolitionists, elder statesmen, great-aunts: They’re all present, looking as if they might suddenly say something to the viewer. Daniel Webster is his usual stern-minded self (but seems to have a bit of a belly), and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow has a poetical air. The photographers took extraordinary pains with each commission, adjusting the pose, the expression, the hair, the lighting. Without fail, the subjects are elegantly dressed. Their clothing, given the photographers’ technical proficiency and the character of the daguerreotype process, has a pungent immediacy. The blacks and the whites can be subtle, palpable, luscious. You can almost feel the velvet or smell the wool.

These daguerreotypes, obviously important to the history of photography, can also be enjoyed as historical artifacts: Southworth and Hawes created some very unusual documents, such as a depiction of a surgical operation that foreshadows The Gross Clinic of Thomas Eakins. What’s surprising, however, is that certain of the daguerreotypes are also great works of art—images of jolting expressive power. Southworth and Hawes were lively, open-minded experimenters, both technically and artistically, who took advantage of whatever their medium could offer. In their sensibility, there’s nothing awkward or provincial. They are well aware of what makes a great painting; their best compositions contain lively visual rhythms. Although the poses they employ are often formal—this was a formal age—their subjects do not appear stuffed. Their presentation of character is shrewd without being intrusive. The vanity of these Yankees is often amusing: One celebrated man of God has an all-points hairdo that must have been as difficult to attain as the path of righteousness. Certain pictures simply astonish. In one, Southworth and Hawes made an almost abstract study of clouds over a rooftop. Another depicts frost curlicues on a window. A picture of a small child on the floor, swaddled in the blur of eternity, has the immediacy of a snapshot.

Such photographs create in viewers a yearning for something more. That vain preacher may be intensely present, for example, but he is also ineffable. He cannot move. He can’t actually be touched. He has no voice. He awakens but does not fully satisfy our longing for the palpable riches of the past. He is, finally, a ghost.

Our memories, similarly, can never fully recover what’s lost to time. If photographs enrich the past, they also embody and symbolize its poignant losses. In a brilliant complementary exhibit to “Southworth & Hawes,” Geoffrey Batchen is presenting “Forget Me Not,” which includes a selection of photographs that people have doctored, changed, and generally souped up in an effort to add lost dimensions—above all, the sense of touch—to the naked, stand-alone photograph. A wedding picture is encased with the bride’s veil and the groom’s lapel rosette. The image of a woman who has died includes tangible wax flowers. These private altars to the past can be creepy, like a reliquary containing the fingernail parings of a saint, but they are also poignant and soulful. Most of them, designed to hold onto the details of the past, are now themselves anonymous in all respects. They’re for sale in flea markets. Photography, said Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1859, is “the mirror with a memory.” A mirror that cracks.

Louis Daguerre’s 1839 invention set off a photography craze, especially in New York. Within two years, the city had 100 studios, many on lower Broadway. The technology’s chief proselytizer was none other than Samuel F. B. Morse, who’d heard about it while in Europe drumming up interest in his own invention—the telegraph—and tried it out for himself. “My first effort was on a small plate of silvered copper,” he wrote later, “and, defective as the plate was, I obtained a good representation of the Church of the Messiah … from a back window of the New York City University. This I believe to have been the first daguerreotype made in America.”

Young America: The Daguerreotypes of Southworth & Hawes

Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance

International Center

of Photography.

Through September 4.