The popularity of Monet, Cezanne, and Van Gogh cannot be explained by art alone. The reverence with which they are treated and the crowds they attract have a quasi-religious aura. People seem to want to hear stories about their monkish devotion to their calling: Van Gogh, in particular, is widely regarded as a kind of saint. Shunned by bourgeois society and living among prostitutes and outcasts, he struggled to create a visionary art for an indifferent world. Then, after his suicide, he underwent a form of apotheosis. (If someone were to find his severed ear and place it in a reliquary, thousands would make the pilgrimage to pay their respects.) Like the church, museums know that saints are good for business – show business – and have presented as many exhibits about these particular artists as possible, often emphasizing their personal history.

Cezanne to Van Gogh: The Collection of Doctor Gachet, which opens this week at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a deftly conceived exhibition in this tradition. Jointly organized by Susan Alyson Stein and Anne Distel of, respectively, the Met and the Musee d’Orsay in Paris, the exhibit includes about 100 Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings and drawings borrowed mainly from the Musee d’Orsay and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. All originally belonged to Dr. Paul-Ferdinand Gachet (1828-1909), the eccentric physician and collector who attended Van Gogh during his last days. In keeping with the personal air of such exhibitions, the curators have included many relics of the Impressionist milieu. For example, you can look at an actual vase belonging to Gachet that Cezanne painted, flicking your eyes back and forth between the image and the reality, and admire pieces of the true cross: the paint-encrusted palettes of Cezanne and Van Gogh. Also on display are many copies – in their way, acts of devotion – that Gachet, his son, and others made of works of art they owned.

Gachet was a restless man of quixotic enthusiasms. As a young doctor, he seems to have spent more time socializing in the cafes of the Parisian art world than practicing medicine. He knew Manet, Seurat, and Baudelaire; he occasionally tried his hand at painting and art criticism, and he became a determined etcher. He was interested in homeopathic medicine, and he dabbled in various esoteric and hothouse Parisian pursuits, belonging, for example, to an association called the Society for Mutual Autopsy. (In our era, he would have been a New Age herbalist with a vacation house in Santa Fe.) In 1872, he bought a house in Auvers-sur-Oise, about an hour’s commute from his medical practice in Paris. A number of artists lived in the area, notably Camille Pissarro, a father figure to the impoverished Impressionists. The doctor and “Pere” Pissarro soon became friends. Gachet began to collect Pissarro’s work, which cost little, and Pissarro introduced Gachet to many of his young friends, notably Cezanne and Guillaumin.

The Impressionists often painted in and around Gachet’s house. The doctor, who quickly became a passionate devotee of their work, would perform medical services in exchange for a painting or, occasionally, purchase something for a few francs. Quite a few pictures probably came to him for nothing at all, abandoned by the painters as loose studies or experiments; some were painted on cardboard. The show includes a strong selection of work by Guillaumin, a secondary figure too often ignored in conventional accounts of the period, and presents Cezanne at a critical point of transition. During the period when he was close to Pissarro and Gachet, Cezanne was beginning to move away from his dark and tumescent early work. Here, you can see him starting to master the Impressionist style, sending himself to school through a close study of Pissarro’s work. The show also includes Cezanne’s delightfully bizarre A Modern Olympia (Sketch), in which a man – probably Cezanne himself – and a little rococo dog earnestly study a cloud-festooned nude.

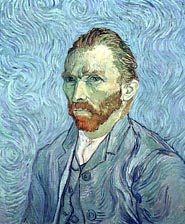

It was at Pissarro’s recommendation that Van Gogh, weary of his life in the asylum at Saint-Remy, moved to Auvers in May 1890. He spent the last 70 days of his life under Gachet’s care. The period was one of fiery, all-consuming work for Van Gogh, culminating in his suicide in late July. Van Gogh paid the doctor in paintings, and while many have wondered how effectively the painter was treated, the curators believe Gachet was a helpful, benign presence in the artist’s life. Two great Van Gogh paintings are in this exhibit, a self-portrait and Portrait of Dr. Gachet. The latter wonderfully captures both the vanity and the wry, peculiarly Gallic melancholy of the doctor. (His little peaked cap is one of the relics in the show.) Even the flowers in Van Gogh’s portrait appear world-weary.

Gachet’s wife died in 1875, and he never remarried. He had a son who, like his father, seemed to live vicariously through art. After his father’s death in 1909, Gachet fils (1873-1962) spent most of his life locked away in the Auvers house hoarding the past. He worked endlessly on a book about Van Gogh and, with some others, carefully made copies of the family pictures. To support himself, he would occasionally sell a painting. He rebuffed the requests of writers, curators, and historians to study the collection. This naturally aroused both great resentment and great curiosity; it also raised many false suspicions that he was busy making forgeries to sell. Beginning in 1949, he began donating parts of his collection to the French state. It was not until his death in 1962, however, that art historians could really begin to unravel the story of the Gachets. This exhibition finally clears up most of the remaining questions.

As a rule, crowd-pleasing shows that emphasize the personal stories of painters end up directing attention away from the art. They are the reflection, in short, of a culture that prefers artists to art and celebrity to achievement. But that is not the case here. Oddly enough, this is one of the best shows I have ever seen for training the eye. The main reason is that the curators have hung so many of the copies that Gachet, his son, and others made of the pictures in their possession. The opportunity to analyze the differences between an original and a pale but competent copy illuminates as nothing else can what makes art art. Same subject, same composition, same palette; yet one picture is dimly dead, the other luminously alive. Even lesser works by great artists, of which there are many in this show, have the force of necessity – a kind of palpable life in the brush.