Many great modern artists have had nothing to say – at least directly – about the tragic events of their time. The French, in particular, were masterly at cultivating the principles of pleasure and order even as the world around them flew apart. During World War I, as Europe became a charnel house, the Cubists remained in the Parisian cafés investigating the finer points of form. And Matisse and Bonnard never felt obliged to abandon the radical dream of paradise to report the facts from hell. Does this detachment represent an ostrichlike blindness to history? Of course. But it can also be an essential blindness, one that protects other forms of sight. Not everyone can or should be a tragedian, and art is often best not when it reflects brute reality but when it keeps alive what is forgotten or dimmed by the shadows.

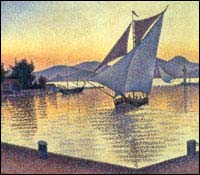

Paul Signac (1863-1935), whose luminous retrospective opened last week at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is part of this French tradition. Signac was a political man, concerned with suffering and the revolutionary fervor of his era; occasionally, his views entered his art. But he usually argued for a more indirect link between art and the tormented world. “Justice in sociology,” he wrote, “harmony in art: the same thing.” Signac chose to create an aesthetic preserve of orderly joy, one in which the endless floating bits of existence are recast into a harmonious whole. (A friend of mine, freshly aware of the terror of the broken, said she wanted “to crawl into his pictures.”) Among his sailboats and shimmering seas, he could engage in painterly researches into a perfected world. In the catalogue, the organizer of the show, Susan Alyson Stein, described Signac’s ideal as being “completely in control of his means but with such ease and seeming casualness of execution that his results were disarming.”

The actual art-historical purpose of this show is to help Signac escape from the shadow of Georges Seurat, the master theorist of pointillism, or divisionism – the theory upon which Signac founded his own work. Seurat proposed making art based upon a scientific understanding of optics and color. He came to believe that an artist could mix dots of primary colors in such a way that at a distance, they fused in the eye – creating an especially vivid, luminous image. As a young man, Signac, a self-taught painter, adopted Seurat’s ideas with the fervent devotion of a convert. Although Seurat himself died young in 1891, Signac retained his friend’s system for most of his life, tinkering with but never abandoning its principles.

As the show and catalogue suggest, Signac had a warmer, more romantic sensibility than the strict Seurat, who maintained a Pharaonic reserve. Signac, loosening the collar of the theory, let his brush play more in the paint. His color had more juice, his light more fire. A passionate sailor and yachtsman, Signac liked the bulge of a sail and had a strong feeling for the physical presence of the sea. Theory could not, for example, dry out his sense of the wetness of water. (He became deft with watercolor, a medium that spills across boundaries.) He made his best work during a relatively brief period, from the late 1880s until the early to mid-1890s. In the seascapes of those years, logic and passion seem ideally joined: The luminosity is truly rapturous. Later, he became merely talented, especially in his more ambitious works. Under the influence of romantics, something rather strained, sugary, and grandiose – a romantic flush – upset the perfect poise of his earlier approach.

A complementary exhibit at the Met, “Neo-Impressionism: The Circle of Paul Signac,” demonstrates why Signac will never quite succeed in escaping from Seurat’s shadow. The show, which was organized by Dita Amory, contains some pictures by a number of artists working with divisionist ideas – but also some pictures by Seurat himself. Seurat’s dominance over the field is absolute. Seurat is his theory: What promised to be a system for all proved to be the sensibility of one. Seurat cannot be copied; his art is sui generis and makes his followers look, by contrast, sort of sloppy and charming. The strongest among them, such as Matisse, realized this and soon went their own way. In his best work, Signac always transcends charm, yet he can leave the eye longing for something firmer – something more like Seurat’s otherworldly austerity.

The street mobs of the French Revolution, as they helped sweep away the old regime, brought to the fore a great new subject in art – the nature of the modern crowd. Generations of modern artists have now addressed this volatile, ever-changing subject. In our time, no one has been more successful at depicting the play of the contemporary street than the photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia. Over the past few years, his pictures taken in such places as New York, Tokyo, and Los Angeles have captured the strangely abstract, hurrying air of the people; the glossy shine of the clothes and the postmodern habitats; and the random syncopation of crossed paths and passing meanings. For his new show, Heads, at PaceWildenstein in Chelsea, which continues until October 13, diCorcia has in effect slowed down the shutter and moved in close to the moving crowd – spotlighting solitary faces as they emerge onto a street. Each face seems to present a kind of sudden, individual glint, like the momentary flash within a school of fish.

These are not upbeat portraits: A melancholy air suffuses the illuminations of a postman, a security guard, a girl in a T-shirt. Yet diCorcia’s photographs do not milk the usual clichés about alienation and “the lonely crowd.” He uses the elements of fashion to spotlight the heads, but the heads are neither those of stars and models nor those of the officially sad or downtrodden. They are not selling anything, especially not themselves. Nothing is confessed. Thoughts are not delivered. Many of the heads and shoulders form a momentary pyramid in the surrounding vagueness, which gives them strength. DiCorcia’s treatment of the background or “negative” space around the central image – often a formal weakness in photographs – is especially evocative. His whispering darks almost become part of the heads. They take the place of the halo in the earlier depictions of mysteriously illuminated figures. They represent the blur of consciousness. DiCorcia is here building monuments to the unknowable, in a culture that hungers to know all.

Signac, 1863-1935: Master Neo-Impressionist

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art; 10/9-10/30.

Heads

Photographs by Philip-Lorca diCorcia; at PaceWildenstein Gallery; through 10/13.