Near the beginning of Reflections in Black, the historical survey of African-American photography organized by Deborah Willis at the Studio Museum in Harlem, there is a remarkable photograph by William Earle Williams of a tree on Jamestown Island – the site in Virginia where Africans first landed in America and where, later, the Confederates built a fort with slave labor. The tree has a sharp kink in its trunk, as if it had been convulsed with pain. At the top of the image is a leafy canopy; in the foreground, shadows; and far ahead, over the water, a promising sliver of land. If this picture is a poetic evocation of the black experience in America, the exhibition itself – drawn from the Smithsonian – documents the actual chapter and verse of the black story. In more than 250 photos taken by dozens of photographers over 150 years, viewers can see brought together countless aspects of black culture, from portraits of families to the social activism of the sixties and seventies.

What unifies the show is a sense of historical optimism – an unspoken confidence that, like that tree in Jamestown, African-Americans will prevail over the pains of history. There are few pictures here of poverty or despair. (The recent survey of black photography at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, “Committed to the Image,” while different in certain respects, conveyed a similar optimism.) “Reflections in Black” therefore provides an ideal accompaniment to Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, which opened last week at the Whitney Museum of American Art. In contrast to most of his contemporaries in art, Lawrence (1917-2000) was no cultivator of modern angst. He had more important things in mind. He sought to capture the deep underlying song of black experience, and he thrilled to the forward, propulsive movement of black history. His strongest work came in storytelling cycles of imagery, above all in the 60 images of “The Migration of the Negro,” which he completed in 1940- 41. For this show at the Whitney, which was organized by Elizabeth Hutton Turner for the Phillips Collection in Washington and Barbara Haskell for the Whitney, Lawrence’s full migration cycle is on display.

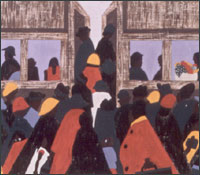

Lawrence began with the basic themes underlying the migration of more than 1 million African-Americans to northern cities – such as poverty and discrimination in the South, the need for workers by industry, the eruption of race riots in the cities. He then used modernist ideas – flattened shapes, simple fields of color, skewed perspectives – to create images to evoke these themes. But the actual work doesn’t look like a calculated modernist exercise about contemporary events. It seems more timeless than that. Almost everyone who sees this cycle thinks of spirituals and folk music. As you move past the lilting images, certain elements – particularly those concerning movement and railway stations – recur like a phrase repeated in a blues song. (The cycle ends “And the migrants kept coming.”) Many images bring abstract ideas brilliantly to life. To convey the anxiety of southern blacks who were considering moving north, for example, Lawrence shows a group huddled in conversation at a table, with a large open space looming nearby and a plant whose stem seems to beckon like a finger.

Lawrence’s hope is strengthened by his melancholy. He developed a deep oxblood palette, much like the rich darks in the voice of a great black singer. He also kept the sun away from his light, giving his pictures a moonlike radiance. He made several other important cycles of images, including one concerning World War II, and a wonderful children’s book about Harriet Tubman, but none has the enlarging power of “The Migration of the Negro” – perhaps because Lawrence was, at heart, a miniaturist. Unlike so many ambitious artists of the twentieth century, Lawrence had no bombast in his sensibility. His pictures are small by the standards of our time. He is not driven to make himself the story, to step in front of the band for a solo. For Lawrence, it’s always the song, not the singer.

Reflections in Black

At the Studio Museum in Harlem; through 12/16.

Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence

At the Whitney Museum of American Art; through 2/3/02.