Like Sherlock Holmes investigating a mystery, a critic of contemporary culture should notice the dogs that do not bark. Among the unexpected silences of today, the most significant to me is the lack of sustained interest in ideal, perfected, or revolutionary states of being. Where are the social utopias, the celebrations of a transformed consciousness, the visions of renewal and rebirth? Given the new millennium and the extraordinary scientific advances of this time, it seems strange that so few contemporary artists have a hopeful or otherworldly gleam in their eyes. Today, the future is typically regarded with dread.

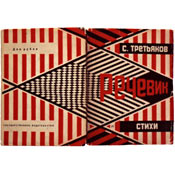

In this respect, past art can illuminate what’s missing from the present. At the Museum of Modern Art,The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–1934 depicts that fertile period – before Stalin slammed the door on dreams – when Russian artists believed that the modern world would yield a new kind of man. Organized by Margit Rowell, the show celebrates the Judith Rothschild Foundation’s gift of more than 1,100 books and related materials to the museum. Most of the best artists of the period – among them Natalia Goncharova, Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandr Rodchenko, and El Lissitzky – are represented in the show, for the book form offered artists an ideal vehicle for their revolutionary aspirations.

A book can embody a civilization: The word becomes a world. For most Russians at the turn of the last century, “the book” – as traditionally understood – evoked either the religious orthodoxy of the church or the settled taste of the wealthy. Not surprisingly, revolutionary artists challenged their society by subverting the visual and verbal authority of the book. In the early days, the Russian Futurists created volumes that welcomed surprise and emphasized the private and idiosyncratic over the expected. Their books were often rough and handmade, and seemed one-of-a-kind. Not surprisingly, artists and poets formed a strong alliance in the creation of such books, for poets were also searching for a new language to describe the evolving face of modernity. In many books, the words seemed to be scrawled by hand among primitive pictures. Letters, words, and typefaces did not hold a line but instead wandered around the page, as if searching for their meaning.

The Futurist books were steeped in private dreams. After the Revolution of 1917, however, artists became more concerned with building a society – not just imagining it with their friends. The style of geometric abstraction called Suprematism (which Malevich developed shortly before the Revolution) brilliantly anticipated this social purpose, for it brought together the logic of the machine age and mystical dreams of modern transformation. Suprematism seemed to mix its geometries with the open sky. It could serve both fantasy and the factory. With a Suprematist outlook, an artist could at once honor and upend rules in a rectangular book full of horizontal lines. Lissitzky created a children’s storybook whose protagonists were a red and a black square.

It wasn’t long before the new Soviet leaders regarded too much openness and freedom as a personal indulgence – and urged artists to put aside their individual sensibilities in order to serve the broader public purposes of the Revolution. Nonetheless, the Constructivist graphics developed by Rodchenko and Lissitzky, in particular, retained a vivid sense of movement and possibility. Rodchenko would often invest his patterns with a kind of optical shimmer; the tremble of the eye seemed to prepare the excited mind for the new thoughts contained in the book. Lissitzky would create forms that never seemed quite contained by their page – they always implied some larger space beyond the pale. When the Soviet masters became concerned that art was now too abstract, great artists like Rodchenko and Lissitzky began to incorporate photographs in their work. But they still didn’t allow the “realistic” photographs to root themselves into the page. Their photographic imagery, like their abstract shapes, continued to move and float: The ultimate reality had not yet settled into focus. Eventually, of course, the Stalinists succeeded in taking the air out of this revolutionary art, grounding it in Communist orthodoxy. There is no darker ending in the history of art.

The New Way of Tea, jointly organized by the Japan Society and the Asia Society, honors one of the great efforts to locate paradise. To many Westerners, the Japanese tea ceremony seems impossibly arcane, fussy, and artificial. It can certainly be that, especially to those without much imagination. Its true power, however, stems not from artifice but from the respect it pays to the actual rather than to the fanciful. Paradise is not a far-off land. Paradise is the cup in your hand. On the most basic level, the tea ceremony focuses – and orchestrates – each of the senses. The eye is warmed by the shape of the objects, the hand by the feel of the clay bowl, the nose by the smell of the fire, the tongue by the taste of the tea, the ear by the sound of conversation and the murmur of nature beyond the door. A sensation of order, occasion, and beauty prevails, but none of these qualities oppresses the spirit by seeming too grand. Neither the tea objects nor the tearoom, for example, is very showy or “perfect”; tea masters often talk about “the art of the artless.” And, of course, the ceremony itself was founded upon friendship – upon the egalitarian give-and-take between host and guest and the nourishing of mind by mind.

Organized by Masakazu Izumi, director of the International Chado Culture Foun-dation, the exhibit includes some historical material, such as objects used by the father of the tea ceremony, Sen Rikyu (1522– 91). But the exhibit admirably emphasizes a more difficult aspect of the genre – the response by today’s architects, designers, and craftsmen to the way of tea. For example, the show includes a number of newly conceived tearooms. One is an open cube – a kind of conceptual tearoom – that looks rather like a sculpture by Donald Judd. Another is an evanescent grouping of planes focused upon a basin of water. Still another creates an orderly space from metal scraps. Such works extend a great tradition yet do not quite reach what they admire. They are not just “the way of tea”; they are about the way of tea. In their presence, visitors become intellectuals and outsiders looking in. This kind of contemporary distance always provokes in me an intense desire for more direct experience. Elsewhere at the Asia Society, there’s a room full of powdered green tea. Its extraordinary smell requires no thought, which seems a blessing.

The Russian Avant-Garde Book, 1910–34

At the Museum of Modern Art; through 5/21.

The New Way of Tea

At the Asia Society and the Japan Society; through 5/19.