Richard Avedon’s celebrated photograph of the model Dovima posing like a ballerina between two magnificent elephants was made, in 1955, to advertise a Christian Dior dress—but no one cares anymore about the fashion footnote. The image immediately became a seminal depiction of beauty and the beast; a woman, with a bewitching gesture, could tame the wild heart. The photograph evoked circus performers and Indian princesses as well as the stylish women of Paris, and was unlike anything in the serious art of the time. It was light-hearted, not earnest, delightfully silly as well as sublime. When I first saw it, in the seventies, I remember wanting to go there, away from the wan theorizing of art, and enter the fairy tale.

All great fashion photographs similarly transcend what they advertise, creating a distinctive mood or dream. For much of the twentieth century, however, fashion photography was circumscribed by the smallness of its milieu of wealth and haute couture. Serious modernists treated it with condescension, as an inauthentic and corrupted form of art—if it was an art at all—that merely flattered the rich. That began to change after World War II when fashion exploded outward, with pop and youth culture providing many of the sparks. Today, fashion looks less like an exclusive club than like an enormous kaleidoscopic theater without walls. Fashion strikes poses, generates stories, produces surprises, and creates fevers. It toys with movies, gossip, celebrities, history, painting, music, and bits of glitter; it plays, really, with almost anything. Boundaries exist, but only to titillate. Fashion still moves merchandise, of course, but fashion’s shifty face has also become an essential reflection of who we are: Artful fashion is often better than fashionable art. Like Avedon, the best photographers make something lasting from the fancies of the moment.

Fashioning Fiction in Photography Since 1990 at MoMA QNS—a fresh and provocative show—spotlights work of our era with this ambition. Organized by Susan Kismaric and Eva Respini, it begins with an emphatic lampooning of conventional fashion, as if to clear the eyes of the usual imagery and remind you that this is not your mother’s Vogue. In “The New Cindy Sherman Collection,” which appeared in Harper’s Bazaar, the artist depicts a series of demented models vamping idiotically for the camera. Then, in “The Clients,” originally published in W, Juergen Teller demystifies haute couture by turning famous socialites into just faces in another crowd. (Anne de Bourbon, no Dovima, stands beside a rude little elephant.) Most of the photographers, as the curators emphasize, are now drawing inspiration from the movies or from the private snapshot—both important sources for recent art in general. The curators have selected the work of thirteen who have created particularly memorable “fictions.”

Of course, MoMA’s willingness to address—the academic buzzword is validate—commercial photography is itself revealing. Photographers like Avedon and Irving Penn once distinguished between their work in art and fashion. Today, art is where you find it. A fashion house obviously places certain important constraints, stated and unstated, upon the imagination of an artist. But those constraints are not necessarily more onerous than those that a king, aristocrat, or priest imposed upon artists in the pre-modern era.

The requirements of a commission can also liberate the eye, as the rules of rhyme and meter can inspire a poet. A photographer with a job must look outside himself, escaping from the private navel-gazing of so much contemporary art. If the subject is just fashion, moreover, a photographer has a license to explore ideas and moods—as Avedon did with his joyful picture of the elephant girl—that may no longer interest respectable art. Fashion is art’s painted whore. She’ll do anything. That’s sometimes worth the price.

The dreams purveyed in “Fashioning Fiction” are, not surprisingly, frequently about longings in our culture. For a certain form of lost beauty, among other things. A painter like Boucher, Van Dyck, or John Singer Sargent could create a stylish surface seemingly without trying. That was largely the point, that the art remained on the surface. Paradise is untroubled by depths; it is hell that’s profound. Today, few artists can find a contemporary way to convey that delight in surface. For a Prada campaign that could be called “Life Is a Beach,” however, Cedric Buchet did create a blissfully vacant paradise—a surreal world populated by models (above) busying themselves doing nothing on the sand. Cropping sharply and employing various movie devices, which establish a contemporary visual tempo, he integrated them perfectly into their environment: Their garments make a just-so tonal match with the sand. The models have untroubled skin, hair, and minds. They attain their clothes.

More often, however, photographers now create a strange after-image of perfection. The women in the Sherman collection are so grotesquely distorted that, paradoxically, they call their opposites to mind. A grungy setting may create a similar after-image. In “Oh de Toilette,” a series from Tank, Simon Leigh makes painterly photographs of inelegant bathrooms in which fine shampoos and talcs and the like have fallen behind radiators or spilled on the floor. Nan Goldin, in a 1985 View, presented shots of ordinary women (at least one of them pregnant) lounging around the moldy Russian baths in lower Manhattan. The spaces in Mario Sorrenti’s photographs are so cluttered, so crowded with the junk of a low-rent pack-rat existence, that clean, elegant clothes become a saving grace and emptiness a poignant dream.

Spontaneous feeling also appears as something elusive but desired. Often, photographers invade the domestic space of the family, usually an emotionally intense arena. But fashion seems to flash-freeze families. The figures in Tina Barney’s “New York Stories,” which appeared in W, could inhabit dioramas in the Museum of Natural History or become wax figures in an art-world Madame Tussaud’s. In Steven Meisel’s “The Good Life,” a campy send-up of ads from the fifties in Vogue Italia, everyone in the family has a Pepsodent smile bright enough to resist decades of Coca-Cola drinking. The wealthy family in Larry Sultan’s “Visiting Tennessee” (a Kate Spade campaign) tours around New York City with a daughter named Tennessee doing its best to become a snapshot. At the Chelsea gallery they visit, monochromatic abstractions hang on the wall.

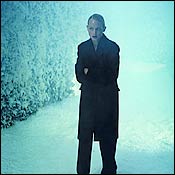

The heightened drama found in the movies attracts the most intense longing of all. Film noir, which is both highly stylized and filled with crimes of passion, is a particularly important source. In Glen Luchford’s homage, something awful seems about to happen to women who wear Prada in dark places, such as a beauty walking in bluish snow (opposite page). In one image, Luchford shows a pair of legs, which may belong to a dead woman: The sandals look exquisite on a corpse. Ellen von Unwerth, for an Alberta Ferretti campaign, taps the nostalgic memories of Marilyn Monroe and perhaps Jackie Kennedy, both women who led lives that have the mythic quality of the movies.

A special form of storytelling characterizes many of the pictures on view in “Fashioning Fiction.” Something appears to be happening in them, some intriguing plotline that is kept from the viewer. This creates a strange, voyeuristic hunger for what’s in the image. The viewer must look for the plot as well as for the clothes. You buy a dream, a story, an attitude, a mood, and a dress. Strong photographers sense that this hungry, outside-inside voyeurism also reflects a deeper existential craving—that found in a fluxy society filled with people of changing identity who are not certain of their private plotlines. In “Cuba Libre,” in W, Philip-Lorca diCorcia placed a woman in fashionable clothes amid the crumble and decay of Havana. Many of the images, in contrast to the libre of the title, suggest enclosing or imprisoning spaces. We do not know her story, but it seems disturbing. She’s an isolated jewel, a prisoner of style.