John Currin is one of the clever boys of art. He knows how to attract a crowd, create a charming surface, and address fashionable themes. He’s naughty; he delights in smarts; he likes a good spoof. Traditionally, clever boys flourish in highly mannered environments, such as palaces or seminar rooms, and they appear regularly in the history of art. On occasion, they have a significant impact. (Manet was being a sublimely clever boy when, in Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, he inserted two Parisian gentlemen and a pair of naked women into a Giorgionesque pastoral.) The clever-boy approach is typically employed, as the phrase suggests, by young artists out to make a name for themselves. Over time, some leave the manner behind, darkening or seeking other, less mischievous apprehensions of the world. Others play the game into old age.

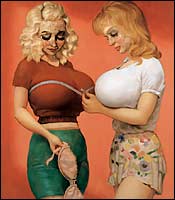

Now the subject of a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art—organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and the Serpentine Gallery, London—Currin first made a name for himself by flouting taboos about the sexes. That’s what clever boys do. In our society, for example, it’s now a no-no to present women as vapid, saccharine creatures. But Currin often does so, creating in viewers the enjoyable feeling that uh-oh, someone’s being bad. He doesn’t take a real risk in portraying women like this, for he’s also investigating “the politics of representation” and satirizing the Hallmark view of the world. In many pictures, he distorts the body (a classic Mannerist device) in order to create startling effects. He painted a series of women with gargantuan breasts, for example, angering feminists and titillating the booboisie. To any criticism, however, he could answer, Who, me? Isn’t the distortion just a lampoon of a silly male obsession? That ability to play both sides—rather than any real violation of taboos—gives Currin’s art its unsettling ambiguity. He always has his cake and eats it too.

Like many other contemporary artists, Currin loves to showcase art history. One painting will recall Botticelli, another Lucas Cranach, still another Mantegna. He treats the old masters much as he does the women in his pictures. He brings a pop irreverence to every quotation. An earnest scholar of the Renaissance would recoil at seeing his tradition treated so cavalierly, with kitschy girlies stealing into the grand old images. Even so, Currin’s irreverent view of the past is also safe, and by now a conventional perspective. Manet took an artistic chance in painting Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, but that was almost 150 years ago. Since then, hundreds of clever boys have teased the past. There is one respect, however, in which Currin differs markedly from most contemporary cutups: He is genuinely interested in the actual art of painting. He clearly loves the masters, intending praise as well as parody. Not surprisingly, he is particularly attracted to a luscious surface and to virtuoso effects. He seems to reach for a compliment when, for example, he gets the pallor of turkey skin just right.

Mannerist strains are a permanent feature of Western art. It doesn’t make sense to argue about them unless you’re prepared to address, in a nuanced way, the ultimate value of this extended tradition. Some people instinctively find such work delightful; others, irritating. The more particular question is, how truly clever is Currin’s version? The answer is, quite. Currin has created a distinctive world, populated by oddly wispy, candied creatures who seem born of an edgy nostalgia—for the pop culture of the twenties and fifties, for the old masters, for the dreamy heat of adolescent sex. He’s able to make viewers wonder, as Andy Warhol did, if the depth’s on the surface. That’s the best trick of all.

There could hardly be an artist more different from John Currin than Arshile Gorky. If “John Currin” is a downtown cocktail party, Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective of Drawings is an epiphany in a meadow. Seeing both shows on a single day at the Whitney will stretch anyone’s sensibility.

This drawings show, organized by Janie C. Lee and Melvin P. Lader, presents the evolution of Gorky (1904–48) from a student of Picasso and Surrealism to one of the first and greatest of the Abstract Expressionists. Like Currin, Gorky was obsessed with the masters—but in contrast to Currin, he was unfailingly reverential in his approach. He seemed to work from within the great tradition, humbly apprenticing himself to the masters, in the hope of gaining their substance as well as learning their skills. Even his most studious “in the manner of” drawings, however, contain something inimitably Gorky. In his Surrealist works, for example, he avoids the fey Parisian touch. He prefers something more dramatic—bolder, brighter, and blacker.

Gorky did not highly value cleverness, talent, or style. (He once criticized a picture by his good friend Willem de Kooning as “too interesting.”) Instead, he wanted to get to the heart of the matter. In his later drawings, as he liberated himself from his sources, he steeped himself in the countryside around him. His line, as it moved across the paper, evoked both the lyrical joy of the natural world and the whimsical wanderings of consciousness itself. He would often add intense slits of luminous, erotically charged color to a drawing; the color seems to cut into and open out the space of the work. Many of the images are almost painfully intimate. Gorky’s hand can be felt in every smudge and line. His drawing has a kind of rough-hewn grace, at once tender and masculine, that’s never oversweet. Gorky’s last years were difficult. His studio burned down. He became ill. He eventually committed suicide. Because the graceful lyricism never left his line, however, the despairing melancholy of the darker drawings seems all the more powerful, like the shadows that close out a summer day.