Art may mirror society, as the cliché suggests, but the best reflections are rarely found in self-consciously topical work. Instead, they appear unexpectedly, as when you glimpse yourself in a mirror you did not know was there. Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration (at the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and A Triple Alliance: De Chirico, Picabia, Warhol (at the Sperone Westwater gallery) provide startling effects of this sort—momentary crystallizations of the here-and-now.

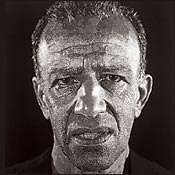

Of course, Close’s monumental heads are among the best-known images in contemporary art—hardly the place, you might think, to find a surprise. His basic scheme, developed early in his career, has been to paint a photograph of a face onto a canvas inscribed with a grid. He has varied the details over time but kept the general approach. Print-making naturally appealed to an artist with such a systematic method. It allowed him to experiment with the process, manipulating the variables in his scheme. Close took up many different techniques, among them etching, aquatint, lithography, mezzotint, linoleum cuts, and woodcuts, and found help from skilled printers. The show at the Met—which Terrie Sultan organized for the Blaffer Gallery at the Art Museum of the University of Houston—contains roughly 100 prints, proofs, and tools of the trade, dating from 1972 to 2002. In one piece of bravura print-making, Close turned to a Japanese woodblock technique called ukiyo-e in which separately carved blocks are used to create a single image. His Emma—a picture of his young niece—required no fewer than 27 different blocks and 113 colors.

The prints are not, however, just a subset of Close’s work. Certain ones have a special character. They seem to capture—in an exciting way—the expressive face of contemporary technology. Close himself probably does not have this particular ambition. And yet some of his prints have a digital aura, including ones made well before digital photography became popular. John (1998), for example, could almost be made of melting pixels. Somehow, mysteriously, the Close grid adapts to changing technologies. (Even the earlier prints have a way of shifting in the eye in order to reflect the evolving world.) “Perhaps the major artists of any period,” Richard Shiff writes in the catalogue, “are those whose personal desires, interests and obsessions parallel the most timely issues that occupy the cultural imagination of their society.” Close seems to have a special feeling for the mechanical underpinnings of modern culture.

At the same time, his art does not yield to the modern machine. Some prints have a machine-fresh light that looks dewy, not mechanical. More important, they have a kind of visual tremble, one caused by tension between the abstruse severity of the overall system and the looser handling within each tiny box of the grid. As a young artist, Close was a great admirer of the Abstract Expressionists, and in his later art, you can almost see small Ab Ex paintings beginning to emerge inside the living cells of his grid. His art is a seduction, not just a declaration, of the grid. The hand is not lost in the pixels.

“A Triple Alliance” is presenting art that not so long ago was considered a cultural embarrassment, something to be mentioned only in a whisper. As young artists, De Chirico (1888–1978) and Picabia (1878–1953) were heroes of modernism. De Chirico’s early dreamscapes were the heart and soul of Surrealism, its Garden of Eden. Picabia’s volatile sensibility was an inspiration to Dada, and his erotic machines helped establish an important theme in modernism. And then both artists threw away their reputations—“drifted off,” as Robert Rosenblum puts it, “into more private territories that led far from the highways of history.”

De Chirico began to violate modernist taste. He flirted in an unseemly way with old-fashioned perspective and modeling. He cultivated an academic air. He made pictures that did not seem to know whether to be crude or polished. Worst of all, he did not treat his own iconic works with pious respect; instead, he counterfeited and cloned them. Picabia behaved no less strangely. His art appeared meandering. He made what looked like pale imitations, or parodies, of highbrow abstract painting. His most embarrassing pictures resembled commercial illustration and, like De Chirico’s, had an art-school air. In a 1933 portrait of the vampy Suzy Solidor, Picabia made no effort to add the sort of modernist touches that would assuage highbrow taste.

De Chirico and Picabia were, consequently, excommunicated from the modernist temple. In 1970, the Guggenheim virtually banished the “bad” Picabia from a Picabia show. In 1982, the Museum of Modern Art did the same to the “bad” De Chirico. The MoMA show, which was particularly heavy-handed and earnest, probably marked the turning point in taste. Artists like Warhol, sensing power in what made the elders anxious, seized upon the later work of De Chirico and Picabia. Young artists came to believe that modernism, which began as a youthful rebellion, had itself evolved into a defensive Establishment. You can see the influence of the bad De Chirico and Picabia not only in Warhol but in many artists working today, from David Salle and Sigmar Polke to John Currin. Once again, De Chirico and Picabia have become heroes, this time for the rebellion of their later work. The apostates have taken over the temple.

What happens now? That is the startling, unspoken question this exhibit seems to ask. Early De Chirico and Picabia, once upon a time, upended conventional taste. Late De Chirico and Picabia, once upon a time, upended conventional taste. Now the upending of the upending has itself settled into conventional taste. Rosenblum wittily begins and ends his essay in the show’s catalogue with the same phrase: “Times change, especially for art.” Are we always waiting for the new upenders? Is art a merry-go-round of taste? Can you pause to make permanent distinctions of value? Perhaps you can have it both ways. When I stop to look, I still prefer early De Chirico and Picabia—and Warhol. But when I come upon their celebrated embarrassments, I am delighted that they kept moving. They never became their own fathers.