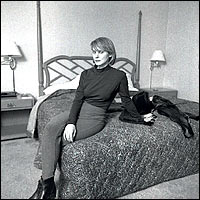

Just before I left my apartment to meet Mary Gaitskill, I slipped off my engagement ring. It just seemed … uncool. Too conventional, maybe, and the Mary Gaitskill I had stuck in my head seemed like the type of person who might not approve—that Greenwich Village waif with the dyed-red bob and deadpan gaze, whose predilection for tales of kink and misery suggested she might disdain such bourgeois display.

Instead, the Mary Gaitskill who showed up on Sixth Avenue looked way more like Marilyn Monroe, if Marilyn Monroe had lived happily ever after. She had the same high cheekbones and big eyes as in her iconic author photos, but she was drained all over to a uniform lemony white: pale skin, a vanilla cashmere turtleneck and white-blonde shoulder-length hair. As we settled into a booth at Café Loup, my eyes were drawn immediately to her hands, where I was startled to see a thick gold wedding band and a honking diamond right out of an engagement-ring ad. Well, hello.

I must emphasize how weird this was, like running into Tom Wolfe wearing torn sweatpants. But as we talked, and Gaitskill described her life over the past decade, as well as her latest novel, Veronica, a nominee for the National Book Award, I came to see this makeover as a logical reflection of her writerly metamorphosis. “I think it actually started in my late thirties,” she recalled over a glass of wine. “I started changing psychologically, and it was difficult to translate that into my writing.” For a while, she considered ditching the whole thing. “I quite frequently felt like I hated it. I don’t want to write. Whatever I had to say, I’ve said it. I didn’t want to keep forcing myself to grind out book after book. But I couldn’t think of anything else to do—it was like I was trying to look out a window for a certain kind of inspiration, and now that window was closed.”

Many writers go through such crises, but in Gaitskill’s case, these feelings must have seemed particularly acute; her writing had always appeared to spring directly from a damaged young woman’s gimlet view of the world around her. In 1988, when her short-story collection Bad Behavior came out, it became a dorm-room bible for women I knew: Finally, here was a fiction writer unafraid to walk straight through the feminist battlefields of that very strange period, when debates over “victimology” and date rape dominated the landscape. Her characters were stunted, smart, mean boys and the women they toyed with, as in “A Romantic Weekend,” in which an intellectual masochist has a disastrous assignation with a sociopath who has a very different idea of what constitutes kinkiness. In “Secretary” (the original source for the 2002 movie starring Maggie Gyllenhaal), a temp gets spanked by her boss, quits, and accepts a guilty payoff. Among writers who dealt with similar topics—and the shelves were full of them in those years, from Dennis Cooper’s nihilistic fantasies to Susie Bright’s chipper sex ed—Gaitskill was something special. She didn’t grandstand; she lacked self-pity. She had an intuitive sympathy for people acting on their worst impulses and a gift for portraying cruelty without condemnation. She managed to be an erotic writer without being, precisely, a sex writer.

Gaitskill herself seemed like a character from her own pages. She too was a downtown girl and a waif, someone who had cashed out her twenties on a series of sexual improvisations. She’d sold flowers in San Francisco as a teenage runaway and worked as a stripper and a call girl. But unlike the characters who populated her books, she was a success—even if that didn’t quite translate into mainstream literary success. It didn’t help that she wrote quite slowly. In 1991, she published Two Girls, Fat and Thin, a flawed novel about followers of Ayn Rand, and in 1998 a terrific collection of short stories called Because They Wanted To. Between books, she wrote for magazines—including a masterfully argued essay about rape that neatly undercut Camille Paglia and Wendy Kaminer, a piece in which Gaitskill described two times she had been assaulted, once by an acquaintance, once by a stranger.

And then she seemed to disappear, Cheshire-cat-like, leaving only her books. A new breed of writers had seized the “fresh young thing” slot—David Foster Wallace and Dave Eggers and then the epidemic of Brooklyn Jonathans. By the time Secretary was released, few people knew that it was based on her short story. (Maybe not such a bad thing, since, to the writer’s distress, her ambiguous vignette had been turned, Pretty Woman style, into a kinky fairy tale with a happy ending.) Now, with Veronica—and the National Book Award nomination—a comeback seems imminent. Like so much of Gaitskill’s writing, Veronica concerns the inner workings of a curdled intimacy: in this case, the exploitative (but ultimately redemptive) friendship between a model and the title character, her embarrassingly uncool friend dying of AIDS—a figure based on a friend of Gaitskill’s. But the book also feels different from her earlier writing, with a dreamy, hallucinatory quality and a new obsession with mortality and aging.

It is also not, strictly speaking, her latest book. Gaitskill wrote the first draft back in 1992, in an attempt to force herself to write faster. Back then, she was living in Manhattan, writing for magazines and shocked by her sudden exposure to pop culture after years of living as a San Francisco bohemian, without a TV or much exposure to the media. (It’s hilarious to hear Gaitskill describe her first sight of MTV and “these weird HBO movies—they’d have people fucking, but with their underwear on,” she says, sounding more than a bit Amish.) “I can be somewhat … impressionistically labile,” she explains with a glance downward. “And I can just get drawn into whatever massive enthusiasm is gripping people at the time.”

That enthusiasm was supermodels, a profession that in the early nineties suddenly became “the highest aspiration that anyone could have,” she says. Aiming to capture the seductive swirl of fashion—“both repellent and an itch you couldn’t scratch”—juxtaposed with the AIDS epidemic, she forced herself to produce at the “lightning speed” of 100 pages in nine months. The resulting draft was a mess—scenes were missing or half-written; it seemed impossible to revise. Still, Gaitskill believed it had “a certain emotional urgency … If I’d thought it was written by a 22-year-old, I’d be very impressed. If it was written by who I was at the time—a 38-year-old who’d written two published books—I’d think it was unbelievably clumsy and immature.”

She shoved the book aside, slowly completed her second collection of short stories, and then fell into the period that she now calls a “dead zone.” She couldn’t write; she couldn’t finish anything she started. Teaching was part of the problem: The better she became at taking literature apart, the harder it was to create her own. Then her father died in 2001. And for the first time, she was in a happy relationship, with fellow writer Peter Trachtenberg, whom she’d met at a Buddhist retreat; when they got married, she was surprised to discover how much her sense of who she was in the world had altered.

“I wasn’t ever anybody who had a political thing against marriage, but I just thought, Why would I want to do that? So when he proposed, it took me aback.” A few months earlier, she’d mentioned that weddings seemed fun, but that you had to get married to do one. “When he presented me with the ring, he said, ‘I know you don’t want to get married, but maybe we can just have a wedding?’ ”

Trachtenberg asked her to wear the ring while she considered her answer. “It was this,” she said, and held her hand out across the white tablecloth, the diamond sparkling frenetically. “At first I didn’t wear it on the engagement finger, because it didn’t fit; but people still knew what it was, it just had that look about it. And I noticed—and maybe I’m just being hypersensitive about this, but I don’t think so—but you know, I really felt I stood out from other people.”

I just felt like people could identify me: Single. Not young. Middle-aged. And I had these big cat-eye glasses on and bright-red hair, and I felt like I had a big arrow on that said, ‘serial killer here.’

At the time, Gaitskill was living in Rhinebeck, New York, far down a country road without a car. To do errands, she’d walk twenty minutes into town, then stop and buy a solo cookie as a treat. “And I just felt like people could identify me: Single. Not young. Middle-aged. And I had these big cat-eye glasses on and bright red hair and I felt like I had a big arrow on that said, ‘Serial killer here.’

“Then when I started wearing the ring, people at the dry cleaner, the grocery, the cookie place, their eye would fall on the ring and be like, ‘Ahh, she’s okay.’ And on the one hand I really enjoyed that feeling. It was just like—a relief. To feel like I could be part of the herd! And people would say, ‘Congratulations!’ As though I’d won the Nobel Prize. But at the same time, it irritated me, just like, ‘If I wasn’t okay then, I’m not okay now.’ ”

She and Trachtenberg wed the week after 9/11. They’d already postponed the wedding once, when her father died, and didn’t want to do so again. Looking out the window in her wedding dress, she watched her guests arrive from Manhattan, looking “stunned and gray.” “It felt very fraught. I mean, getting married does anyway, but I think a lot of people felt like it could happen again at any time. But—it was good! It sounds ridiculous to say, but it cheered people up.”

In this new frame of mind, she had been thinking again about her abandoned novel, and she had shown the manuscript to her new editor at Pantheon. “I was at such a low ebb and so confused,” Gaitskill said, “that if she had said, ‘Mary, honestly, forget it, it’s not good, just put it in the drawer’—I would’ve done that.” Instead, the editor said the manuscript had potential but needed a framing device: The main character, Alison, could narrate it from the present day.

That switch altered the novel significantly, in both structure and meaning. Instead of taking place during the supermodel nineties, Veronica became the reminiscences of an older woman looking back—with chagrin and amazement—at her younger, wilder, crueler self, and trying to reconcile these two people. A former model, Alison is dying of hepatitis C and working as a maid for a man who once photographed her. And while some of the most vivid passages focus on Alison’s youth—the drug-fueled photo shoots and fun parties with horrible people—the book’s emphasis is less on her past humiliations than her current humility. “When I knew Veronica, I was healthy and beautiful, and I thought I was so great for being friends with someone who was ugly and sick,” Alison remembers. “I can just hear my high, clear voice describing her antics, her kooky remarks. I can hear the voices of people congratulating me for being good. For being brave.” Being taken down a notch has cured her of her obsession with surfaces, including her own.

Like Alison, Gaitskill herself seems to have become more comfortable with the person she has turned into. She has a few new drafts in the works; she’s enjoying teaching—currently, a class on short stories, in which she contrasts older writers like Nabokov with contemporary ones. And Veronica’s nomination for the National Book Award may give Gaitskill the success that has eluded her: the literary world’s wholesale acceptance, and all the pleasures and dangers that accompany it.

Then again, maybe she hasn’t changed that much—at least in her ability to relish her slyer, more self-destructive streak. When we discussed reading reviews, she recalled with bemusement and an odd kind of pride her “perverse” reaction to a piece written by James Wolcott when Bad Behavior was published, in which the critic sneered that she depicted women as “dishrags and dickwipes, cold little biscuits slapped across Daddy’s lap.” A few years later, she met him at a party and flirted with him.

Thinking she must be kidding, I joked, “Yes, that does tend to defang people.” But she cut me off with a smile. “No, I meant it. I wasn’t simply doing it to mess with him. One or two times we had dinner. He’s a charming person. A total weirdo, but a charming person … He sees himself as the voice of naïveté and innocence, speaking out against these false sophisticate hipsters who just are wrong and intimidate everybody. And I think he was that at some point in his life, but he’s not that and hasn’t been that for a long time. But you know, I don’t blame him! I too would like to look at a world where everyone is nice all the time. But it just isn’t recognizable.”