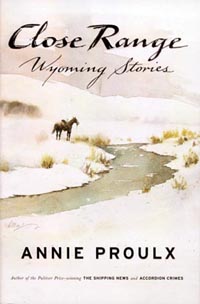

Close Range: Wyoming Stories

BY ANNIE PROULX

Scribner; 283 pages; $25

It’s hard to write about the West, particularly if you’re in love with it. The lure of cheap atmospherics is irresistible, and everything turns to bleached cow skulls, rusty trucks. Either that or a writer falls for clever subversions: the ranch hand with a Ph.D. The West, which was having movies made about it before it was even a quarter settled (and using those movies to define itself while its identity was still in flux), is inseparable from its own representations in a way no other region can be. Every cowboy, no matter how broken-down and gritty, is also playing cowboy, in a sense, and even the rivers and mountains seem half conscious of their roles as backdrops. The West makes actors of those who live in it, and people who write about it are double actors. It’s tricky. No wonder that so much writing about the place either romanticizes, ironizes, or goes crazy trying to do both.

Annie Proulx’s Close Range: Wyoming Stories, is the strongest attempt since Richard Ford’s Rock Springs to capture a place that started as a fairy tale sold to gullible adventurers, flourished as a national matinee, and lives on as an existential broken promise that its people can’t quite stop believing in. Proulx’s territory is northern and central Wyoming, arid cow country far from the vacation spots but close enough to mainstream modern America to feel the cultural pinch. In history, it’s where cattlemen fought range wars, slow to be fenced and still not wholly cut up. It’s a place where Proulx’s characters – mostly tied to agriculture, whether as landowners or laborers – can still get by on minimal educations and a gift for taking things as they come. People still get by on a cash basis here; they pay as they go, financially and spiritually.

Freed from the novel’s demand for momentum, the best collections of stories move sideways, telling the same story over and over again. They vary the angles and the focal points until we can see the subject in the round. Proulx opens her collection by looking backward through a long, fogged lens. Mero Corn is a comfortable old man who long ago left Wyoming for Massachusetts, exchanging ranch life on his father’s old place for a big house and his beloved Exercycle. When his brother Rollo, who stayed behind, drops dead, he hops in his Cadillac for a trip back West. His intention is less to say good-bye than to show off to the home folk how well preserved he is. Families in Proulx are bound by competition, the struggle for scarce emotional resources, and Mero smells victory. It’s not to be, though. As with Xeno’s arrow, the closer he gets to home, the more impossible it is to reach. He ends up spinning his tires in a blizzard, his sedan sinking deeper and deeper into the slush. Aging is the disastrous loss of traction on a surface you used to skip across.

Proulx has a masculine bias in her stories. Women don’t seem to interest her as much. “The Mud Below” follows Diamond Felts, a bull rider on the summer rodeo circuit, from wide-eyed kid to busted-up old hand. Felts is a thrill seeker, damaged and vivacious, and Proulx sticks so close to his physical reality – the long, dusty car trips and wrenching, adrenalized bull rides – that we’re strangely unshocked when we find out he’s a rapist. Violence is the air he breathes, and Proulx plays the scene of his sexual assault as just another ruckus, another dustup. She doesn’t judge him for it any more than she would a race-car driver for speeding. Even the victim takes the rape in stride; she bellows a few curses and moves on. It’s an uncomfortable moment for the reader, especially now that sexual abuse is a major theme in fiction and usually treated as a psychic holocaust, the wellspring of all drama and dysfunction, almost never as just a bump along the road. Proulx is too tough and countrified for hysteria, though, and, like it or not, her characters are, too.

Proulx’s folksy stoicism isn’t a pose. Her stories are solid oak. The simplest and most affecting of them, “Job History,” reduces the life of one Leeland Lee to a list of lousy jobs, failed businesses, and disappointing home improvements. As in the best country music, the pathos is almost unbearable. It’s a story that makes you want to drink, truthful and relentless, plainly told. In its flatness it’s a bit of an exception, though. Proulx’s prose is usually denser. Rustic baroque. She’s a writer who does her thinking by hand, crafting sentences whose specific gravity mysteriously exceeds their size. Her style is all substance, with very little air in it, as though she’s learned to use fewer vowels, somehow, and banish articles and prepositions. “They backtracked and sidetracked and a few miles outside Greybull Diamond pointed at the trucks drawn up in front of a slouched ranch house that had been converted into a bar, the squared logs weathered almost black.” To read Proulx aloud your mouth needs plenty of spit in it.

Close Range is full of salty western slang, and added to the chunky syntax, this makes for a certain corniness at times, as though Proulx were writing while chewing on a grass blade. She lays on the hayseed vernacular awfully thick, both in her dialogue and her narration, but saves herself by getting things so right. She knows the difference between “dang” and “darn” and how to time a crunchy figure of speech so it doesn’t jar the flow of sense. It’s not an easy thing to do, and the miracle is it doesn’t sound like Hee Haw or a bad imitation of John Wayne. At its best, Proulx’s drawl is better than perfect, both heightened and believable. She doesn’t just copy western speech, she deepens it, preserving all its wit and earthiness while trimming away the tired old baloney. If God talked cowboy, he’d sound like Proulx. She’s brilliant.

The stand-out among the stories is the last: “Brokeback Mountain,” the sad chronology of a love affair between two men who can’t afford to call it that. They know what they’re not – not queer, not gay – but have no idea what they are. Just actors. Westerners. Caught up in myths impossible to live out but death to let go of, supposing they even could.

Click here to order this book from Amazon.