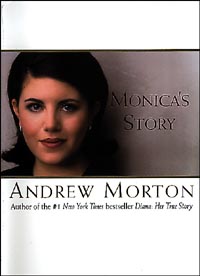

Monica’s Story

BY ANDREW MORTON

St. Martin’s Press; 288 pages; $24.95

If, instead of a therapist, Monica Lewinsky had seen a movie critic or a comparative-literature professor during her sojourn in Washington, D.C., she might have learned that her essential problem isn’t low self-esteem or sex addiction but a tendency to perceive the world as melodrama. How else to explain the uncanny resemblance between Monica’s Story and The Wizard of Oz? Can it be a mere coincidence that both tales tell of a kind young woman, uncommonly trusting and pure of heart, who travels over the rainbow to a grandly corrupt imperial city where she encounters an all-too-human wizard, is set-upon by a wicked witch, and finally awakens from her bad dream to realize that there is no place like home? Chance cannot account for such close parallels. In her own fairy-tale image of herself, Monica is Dorothy with a wardrobe, and if she still has difficulty acknowledging the messy realities of her scandalous journey, it’s because she has yet to lift her dazzled eyes from the Yellow Brick Road.

In Andrew Morton’s retelling of the fable, our heroine is hardly a seductress; she sets out for Washington full of high ideals garnered from her college psychology courses. A sensitive misfit still smarting from the pain of not being properly invited to one of Tori Spelling’s birthday parties, she wins her internship by writing an essay on “the need for psychologists to work in government to understand better ‘the human dimension’ in society.” (Once she reaches her destination, she even gives the president/wizard a book, Disease and Misrepresentation, to aid him in his initiative on race.) It’s hardly her fault that when she lands in Oz, she’s tantalized by “the smell of eucalyptus wafting along the powder-blue carpeted corridors …” and awestruck by the charisma of the great leader. As her good-witch mother now observes, as fully immersed in mythical thinking as her ruby-slippered daughter: “… she knew very little of the real world. She was an innocent abroad in a very sophisticated and cynical town.”

Monica’s all-American innocence is the key to her subsequent adventures, and to her seeming inability to understand her persecution for them. Despite her blossoming sexuality, which excites such bitter envy in Oz’s reigning hags (Hillary Clinton, whom she vanquishes on arrival, and Linda Tripp, who tries but fails to slay her), Monica is a pre-ethical being, short on conscious morality but bursting with instinctive virtue. In pretty much every chapter, Morton takes pains to remind the reader of his heroine’s elemental goodness. “One of the most attractive things about Monica is that she is never mean-spirited.” (This despite her avowed wish to claw the flesh of Tripp.) Indeed, if Monica has a fault, it’s an excessively trusting nature, a habit of putting loyalty before sense. In accordance with Monica’s simple, girlish outlook, people who fail to see her golden soul, such as the White House’s female palace guards who banished her to the Pentagon, are “meanies.” So convinced is Monica of her fundamental nobility that when she’s finally confronted by Starr’s henchmen, she allegedly steels herself by thinking back to a student essay on Hannah Senesh, a Hungarian Jewish poet who was tortured and shot by the Nazis for failing to yield to their interrogations. Monica’s mother even goes so far as to compare her poor baby to Anne Frank.

Everyone takes advantage of Monica’s trust, starting with the president. He too is a kindly soul, at bottom, but power and privilege have made him hard and sly. Still, she sets out to help him, to ease his loneliness. He’s just a man, after all, and in a surprising number of cases she takes time out from their sessions of sexual healing to console him for grievous personal losses: the death of a soldier in Bosnia, of Ron Brown, of Admiral Boorda, of Betty Currie’s brother. And if, as often happens with the president, grieving segues into foreplay, Monica sees nothing odd in this. Instead of evidence for sociopathy or latent schizophrenia, his shifts of focus between love and death are poignant reminders of the burden of power. “… They chatted away far into the night, the President enthralled, actually sexually aroused, by her excited description of the trip to Bosnia. She told him how proud she was to be an American when she saw how the U.S. troops had helped to restore sanity and give hope to this war-torn land.”

No good deed goes unpunished, of course, and eventually the president disappoints her by promising a homecoming to the White House that he has no intention of delivering. This small betrayal is nothing, however, compared to the evil sorcery of Tripp, who “brainwashes” Monica. Like Dorothy in the poppy field, Monica is put to sleep by Tripp, her will anesthetized. Assisted by malevolent flying monkeys (one of Starr’s men is compared to a dog, while another is a “revolting specimen of humanity”), Tripp at last maneuvers Monica into the special prosecutor’s dark castle, where Monica contemplates jumping out the window rather than hurting the man she loves by compromising her code of loyalty. Tortured by the “image of a shackled Susan McDougal,” Monica’s mother rushes to her aid, though, and together the two stand firm against their enemies. Soon, Monica’s father, partially estranged from her, joins in her defense and proves his valor. Like the Cowardly Lion, he finds inside himself a warrior spirit that none were sure he had. By means of sheer mental toughness and solidarity, the reunited family overcomes Starr (whom the overstimulated Morton dubs “a personification of the ‘Big Brother’ of Orwell’s future”), and Monica, sadder and wiser, learns a lesson that, deep down, she probably always knew. Back on the farm, what she wishes for now is “to find a loving partner, start a family, begin a useful career.” And true to her youthful ideals as a crusading psych major, she is even considering “undertaking volunteer work with disadvantaged children, teaching them reading skills.”

Monica has matured, her book assures us, and entered an “emotional convalescence.” One pictures her as one imagines she might picture herself. Like Dorothy, she lies in a sunlit sickbed, both grateful to be home and yet still weak after being whirled in the tornado. Around her, half-familiar faces look down, shining with sympathy. Even the president has wished her well. Unlike her Kansas predecessor, though, Monica hasn’t quite shaken off her Technicolor dreamworld. She sees herself still as a fairy-tale heroine, beset by snarling meanies and winged monsters. One wonders if she will ever fully wake up.