The standard line on first-rate graphic novels is that they’re “cinematic,” or sometimes “literary.” That’s why a lot of third-rate graphic novels give the sense that they’re essentially storyboards for a movie pitch, or a prose story with pictures tacked on.

The French cartoonist David B.’s extraordinary L’Ascension du Haut-Mal, just published in its entirety in English for the first time as Epileptic, supersedes the standard line, exactly as the best art is supposed to. It’s neither cinematic nor literary: At every turn, it does things that only comics can do. It is entirely, obsessively, mesmerizingly the work of a single visual artist, and its narrative is the devastating story of how his vision rose from sickness and despair.

Epileptic is a memoir that’s violently refracted through imaginary images. It opens in 1964, when David B. was a 5-year-old boy named Pierre-François Beauchard, fascinated by the history of warfare and just starting to draw, and his older brother Jean-Christophe began to have epileptic seizures. We see their parents drag the family around Europe for most of a decade in search of anything that might help Jean-Christophe—mostly mystical “miracle cures” from one alternative-medicine quack after another: Swedenborgian spiritualists, macrobiotic masseurs, Rosicrucian Templars. Nothing works.

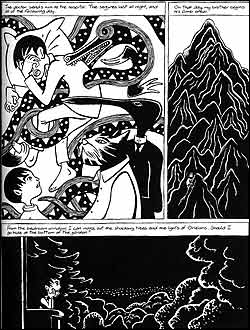

Jean-Christophe commands the family’s attention as he deteriorates physically and mentally; meanwhile, Pierre-François slowly descends into a madness of his own, less malign than his brother’s, but just as powerful. He becomes obsessed with the idea of another reality, and with drawing battles and fantasy monsters. His fantasy life becomes an armor he takes to be literal, protecting him from the bloody chaos of his brother’s illness, but also threatening to seal him off from the world altogether. At the same time, he starts to see a sort of second, metaphorical layer to his physical surroundings. The artwork in Epileptic tracks his perceptions, becoming increasingly elaborate and design-heavy. His dead grandfather has the head of a long-beaked bird; his brother’s epilepsy is a sort of alligator-mouthed serpent with an endless body. The skeletons of soldiers, in their uniforms, are everywhere.

Almost exactly halfway through the book, David (a name he’s adopted in the belief that he thereby “prevailed over the disease”) begins to record his dreams, and gradually gains control of his waking visions. He sets about turning them into his art, the stylized imagery we’re seeing on the book’s pages. As a “bulwark against sorrow,” he draws the crazed, surreal stories that led to his mature work: “Who will seize the reins of power by putting the 50 madmen back in the correct order? … Who is this man leading a flayed child by the hand?”

As David reckons with his baffling visions, Jean-Christophe’s condition continues to deteriorate; he bloats up under heavy medication, surrendering himself to deranged nostalgia for the indulgences of his childhood. In the dream sequences that occupy many of Epileptic’s final pages, David imagines his brother’s face altered again and again by “an invisible adversary”—but the artist himself is the one changing it.

Epileptic is being marketed as a comics memoir in the vein of Art Spiegelman’s perennial Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s recent two-volume hit Persepolis. (B. was Satrapi’s mentor and teacher.) Both of those books, though, use style and visual metaphor as a lens to focus their discussion of history; the way they’re drawn is a tool in the service of the story. Conversely, the way Epileptic is drawn is the point. To read it as a story about alternative medicine in late-sixties France, or even about Beauchard’s family history, is to fail to look deeply enough at its pictures, with their exquisite, ferociously bold lines, as sharp as a woodcut or a scimitar. What it’s really about is the creation of an artist’s identity: how he reinvented his world as a way to “forge the weapons that will allow me to be more than a sick man’s brother.”

Epilepsy has a rich figurative history in Western art. Several Renaissance painters found inspiration in the New Testament story of Jesus’ exorcising evil spirits from a seizing boy. That same story, in which Christ tells the boy to pray and fast, is the root of the ketogenic diet, which film director Jim Abrahams credited with helping his epileptic son, Charlie—a complete recovery he chronicled in the 1997 Meryl Streep TV vehicle First Do No Harm. Tennyson’s brother was said to have attacks, and Frida Kahlo painted her father, a photographer, “because he suffered for over 60 years of his life with epilepsy, but never gave up working.”

Epileptic

David B.

Pantheon.

368 Pages. $25.