Best Literary Fiction

‘The March,’ by E. L. Doctorow

(Random House)In reimagining Sherman’s Civil War march to the sea as a tubular, tentacled, all-consuming dragon-serpent, Doctorow assumes the prophetic role of the nineteenth-century writers he so admires (Emerson, Melville, Whitman, Poe) to write an alternate creation myth for the Republic. Among infantry, nurses, shutterbugs, profiteers, and 25,000 freed slaves, we find not only prototypes of coming attractions in Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor, and Toni Morrison (as well as the young surgeon in Doctorow’s Waterworks and the senior of the Coalhouse Walker Jr. we will meet in Ragtime) but also an elegy for and a bone-scan of an opportunity tragically lost. The fluidity of this second American revolution—of free agency, class mobility, and self-invention, of black slave girls passing for white drummer boys—was strangled in its crib after Reconstruction.

2 ‘Pearl,’ by Mary Gordon

(Pantheon) On Christmas Day 1998, 50-year-old Maria Meyers, a supervisor of day-care centers in upper Manhattan and a Zabar’s of fierce opinion on almost every imaginable topic, is informed by the State Department that her daughter, Pearl, who went to Trinity College to study the Irish language, has refused drink for six days and declared her intention to die in Dublin, chained to the American Embassy flagpole. Maria is on the next flight. What follows is another of Gordon’s fearless inquiries into the hydra-headed nature of truth—about history, religion, politics, justice, violence, and martyrdom; about the death wish, yes, but also, of course, mother love.

3 ‘The Writing on the Wall,’ by Lynn Sharon Schwartz

(Counterpoint) After the attack on the World Trade Center, Renata, a linguist at the New York Public Library, is suddenly asked by the Feds to add Arabic to her other exotic languages (Bliondan, Etinoi), even as she tries to cope with a crazy mother, an importunate lover, a teenage mute, a dead twin, and the child she thinks she lost on a merry-go-round. As starkly elegant as the Chinese calligraphy Renata practices—and superior to the 9/11 fictions of both Ian McEwan and Jonathan Safran Foer in its melding of psychological and geopolitical dream worlds.

— John Leonard

Best Nonfiction

‘The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln,’ by Sean Wilentz

(Norton)This barge of a book (992 pages) confirms Sean Wilentz as the Richard Hofstadter of our day—the supreme political historian. But where Hofstadter wrote history in dazzling generalities, Wilentz both expounds on massive themes and pillages the archives for little-known characters and forgotten movements. (Long live the Locofocos!) He tells a story that parallels George Packer’s book about Iraq—the sweaty, excruciating delivery of democracy—except with a happy ending

2 ‘The Orientalist: Solving the Mystery of a Strange and Dangerous Life,’ by Tom Reiss

(Random House) Though Reiss isn’t a perfect storyteller, he has found the perfect story: a Jewish fabulist named Lev Nussimbaum who re-created himself as a Muslim prince and scholar called Essad Bey (or sometimes Kurban Said). Nussimbaum’s biography includes proto-Fascism, persecution by Fascism, and a childhood in strangely cosmopolitan pre-WWI Azerbaijan. In addition to the charms of its digressions (Kurdish devil-worship, early German film) and the twisted psyche of its subject, The Orientalist is a triumph of research. Piecing together Nussimbaum’s life makes for its own epic tale. 3 ‘Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything,’ by Steven D. Levitt and Stephen J. Dubner

(William Morrow) This book has no thesis, an annoying title, a phony humility, and sundry other grating tropes. Yet it makes such interesting arguments and compiles such counterintuitive data that you can’t help but hang a medal around its neck. Economics, it turns out, can become quite a readable subject when writers connect the Ku Klux Klan to car prices or cheating schoolteachers to sumo wrestling.

— Franklin Foer

Best Debut Novel

‘Beasts of No Nation,’ by Uzodinma Iweala

(HarperCollins)As arresting as the language is in Iweala’s first novel—a hard, clipped pidgin African English punctuated by onomatopoeic “KPAWA”s—it’s the horrific plot, and its numb preteen teller, that makes the book such a rough and dizzying ride. Iweala’s boy narrator, drafted by a guerrilla army on pain of death, is both a victim and, by the book’s end, a repentant butcher. Iweala, born in Washington, D.C., to members of the Nigerian elite, and barely a year out of Harvard, makes an unbelievably imaginative leap out of little more than a few interviews with child soldiers. His confidence in outlining the capacity for evil under extreme circumstances without resorting to do-gooder clichés preempts the inevitable lament—by now itself a cliché—over our tendency to fall for first efforts by privileged young writers.

2 ‘Indecision,’ by Benjamin Kunkel

(Random House)Kunkel’s hilarious and skillful work confronts the bugaboos of autobiographical slacker fiction head-on. His protagonist, Dwight Wilmerding, emerges from his urban postcollegiate ennui with something even Holden Caulfield couldn’t quite muster: a fully fledged social conscience.

3 ‘Summer Crossing,’ by Truman Capote

(Random House) Harp all you want about this being no Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Capote’s rediscovered first novel, published for the first time, makes a great breezy read. His story of Upper East Side debutante Grady’s sultry affair with a lower-class Brooklyn Jew teems with Capote’s trademark wit, but also with genuine youthful awe at the exhilaration of late-forties New York.

— Boris Kachka

Best Academic Book

‘The Economy of Prestige: Prizes, Awards, and the circulation of Cultural Value,’ by James F. English

(Harvard) English, the chair of guess which department at the University of Pennsylvania, has written a book about the manufacture of cultural prestige that is both intellectually shrewd and consistently entertaining. The main currency of this prestige, he submits, is the wildly proliferating number of prizes in the arts—the 4,500 feature films released every year compete for some 9,000 of them. As at least one critic (A. O. Scott) has commented, English’s book deserves to win some sort of award itself, and now it has.

2 ‘The Evolution-Creation Struggle,’ by Michael Ruse

(Harvard) How can intellectually sophisticated blue-staters like us bear to live in a nation where more than half the citizens are benighted enough to think God created man in his present form a few thousand years ago? Michael Ruse, a philosopher of science at Florida State University, is one of the most stimulating writers on the never-ending cultural debate over evolution. Here, this self-professed “ardent Darwinian” arrives at a surprisingly sympathetic view of the anti-Darwin crowd. They may be wrong, but they’re not quite as crazy as we smugly imagine.

3 ‘We Who Are Dark: The Philosophical Foundations of Black Solidarity,’ by Tommie Shelby (Harvard). Shelby, a rising star who teaches African-American studies at Harvard, argues for black solidarity without black racial identity. If that seems paradoxical at first blush, it won’t after you have read this account of black political thought from W.E.B. Du Bois to Malcolm X. Bonus book: Shelby is the co-editor of Hip Hop and Philosophy: Rhyme 2 Reason (Open Court), which improbably lays down a line from Plato to the Notorious B.I.G.

— Jim Holt

Commercial Books

‘The Starter Wife,’ by Gigi Levangie Grazer

(Simon & Schuster)Long before rumors started flying about the breakup of Jessica and Nick (did she really give him the boot by e-mail?), Gracie Pollock, heroine of Gigi Levangie Grazer’s screwball comedy The Starter Wife, got her walking papers by cell phone. Her studio-executive husband was leaving her … for Britney Spears. Gracie gets her revenge in a Hollywood minute, when she meets a grizzled hunk in the surf at Malibu, and Britney gives her cheating ex the heave-ho. Grazer’s novel shows a sharp eye for contemporary foibles and an acute ear for dialogue. Her delectable fantasy is cliché—but name a fantasy that’s not.

Belushi: A Biography,’ by Judith Belushi Pisano and Tanner Colby

(Rugged Land)The list of contributors to this oral history of the comedian John Belushi—put together by his widow and Colby—reads like a Burke’s Peerage of American comedy: Bill Murray, Steve Martin, Christopher Guest, Buck Henry, Dan Aykroyd (who calls Belushi “the only man I could ever dance with”), and so on. Unlike other oral histories, which too often amount to hagiography or simple rambling, this one is suspenseful: Its pieces come together like a puzzle, forming a portrait of a man who was less than a saint and more than a sinner.

3 ‘Lipstick Jungle,’ by Candace Bushnell

(Hyperion)Like the heroines of Clare Boothe Luce’s The Women, with their Jungle Red nails and city-sharpened fangs, the women in Candace Bushnell’s newest novel sniff out power with delicately flared nostrils. They know how to hunt for it and won’t surrender it without a struggle. Unlike Luce’s women, though, their power lies in holding on to their careers, not their husbands. Is this as diverting as Carrie and her Manolos, or Charlotte and her Rabbit? In a word, um, no. But after turning thirtysomething single women into a hot commodity with Sex and the City, Bushnell now is making a damned good effort at turning fortysomething women into the next fetish age group. So here’s to her, for that service to humanity.

— Liesl Schillinger

The Short List

Best Brooklyn Novelist

Nicole Krauss, The History of Love. Krauss’s pitch-perfect rendition of the desperate loneliness of old age bested other, more strenuously sentimental efforts.

Best Queens Novelist

Sam Lipsyte. The insider’s outsider, Astoria’s own Lipsyte finally broke through with his little slacker masterpiece, Home Land.

Best Depressing Novel

‘Veronica,’ by Mary Gaitskill. Happy endings may be de rigueur in the movies, but for literature’s high practitioners, grief is usually the way to go. This year, among the new books from Nobel winners alone, protagonists included a very lonely old man (Márquez), an amputee photographer (Coetzee), and a cancer patient (Gordimer). But Gaitskill’s Alison, an ex-model dying of hepatitis C, has more to offer than contemplations of mortality. The mistress of human loss and longing, Gaitskill puts Alison on a hard road to redemption that’s as beautiful as it is painful to watch.

Most Realistic Portrayal of Sex

‘The Position,’ by Meg Wolitzer. In following siblings deeply embarrassed by their sex-guide-writing parents, Wolitzer shows us the gloriously awkward humanity of bodily union even among those most intimately, ickily familiar with its intricacies.

Best Graphic Novel

‘Epileptic,’ by David B. Translated in full for the first time, the French artist’s story of his brother’s lifelong illness fulfills the enormous aesthetic potential of black-and-white comics.

Best Memoir

‘The Year of Magical Thinking,’ by Joan Didion, is brilliant and heartbreaking—and, for such a media magnet, deservedly backlash-proof. One detractor did write a letter to the Times Book Review to complain that “this obsession with Didion’s obsession with her loss on the part of the Times and other publications has become morbid and tiring.” But the truth is that in a book where “the question of self-pity” recurs regularly, Didion doesn’t wallow at all. She takes apart her own grief so we can better think about—and prepare for—ours.

Best Memoir Other Than Joan Didion’s

‘The Tender Bar,’ by J. R. Moehringer. Sean Wilsey’s Oh the Glory of It All was a close contender for nonfictional bildungsroman. But this journalist’s wistful study of the character—and characters—of a Long Island bar called Dickens, where he visited his bartender uncle from the age of 9, won it by carrying on in the local tradition of Joseph Mitchell and Damon Runyon.

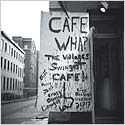

Best New York Book

‘New York Night: The Mystique and Its History,’ by Mark Caldwell. Other books gave us incisive looks at New York this year, like Kate Ascher’s The Works: Anatomy of a City, a wonk’s ultimate reference guide to our municipal infrastructure. But Caldwell’s study of New York after dark—from New Amsterdam pub brawls to Studio 54—taps directly into the city’s collective unconscious. Nighttime, after all, is when the Stonewall was raided, when a 1776 fire engulfed the city, and when Hannah “Man-o’-War Nance” Bradshaw suffered a famous case of spontaneous human combustion. It takes a deft storyteller to pull together such disparate fragments in a grand historical context, and Caldwell manages it well.

Best letter to ‘The New York Times Book Review’

(Reedited by us for length; its clarity was never in question.)

To the Editor:

Jeff MacGregor, the reviewer of Character Studies, a collection of [Mark] Singer’s New Yorker profiles (Aug. 21), including the one about me, writes poorly. His painterly turn with nasturtiums sounds like a junior high school yearbook entry. Maybe he and Mark Singer belong together. Some people cast shadows, and other people choose to live in those shadows… . The highly respected Joe Queenan mentioned … that I had produced “a steady stream of classics” with “stylistic seamlessness” and that the “voice” of my books remained noticeably constant to the point of being an “astonishing achievement.” This was high praise coming from an accomplished writer… . I’ll gladly take Joe Queenan over Singer and MacGregor any day of the week—it’s a simple thing called talent!

Donald Trump

New York

Best Feud

Ben Marcus versus Jonathan Franzen

Like all classic literary beefs, this was a tempest in a teapot, in a year with no shortage of them. (See also n+1’s dismissal of McSweeney’s.) But Marcus’s attack in Harper’s on Franzen’s critique of obscure novelists at least brings us back to a central literary question: What should writers and readers expect from each other?

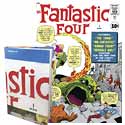

Best Book Jacket

‘Maximum Fantastic Four’

This reprint of Jack Kirby’s classic comic illustrations (with an afterword by Walter Mosley) has a foldout jacket-cum-poster featuring the series’ first cover, designed by Paul Sahre. It does what all good covers must: It compels you to open the book.

Best Blurb

Jonathan Ames, for Periel Aschenbrand’s The Only Bush I Trust Is My Own. “Ribald, outrageous, gutter-mouthed, hilarious—a startling new voice in American letters. Watch out Portnoy, watch out Caulfield, watch out Bukowski, watch out Candace Bushnell. Hell, everybody, real or imagined, just watch out! Because here comes Periel Aschenbrand!”

Best Character

‘Willful Creatures,’ by Aimee Bender. A category with multiple winners: Most of the characters in Bender’s story collection—a tiny technology consultant trapped in a birdcage, a marauding gang of teenage girls that speaks in a collective “we”—don’t have names. Some of the most compelling aren’t even human, like a child with an iron for a head, or a brood of potato babies. But in Bender’s surrealistic yet highly accessible fables, their emblematic struggles for freedom, self-knowledge, or just plain existence somehow become more real the more outlandish their circumstances.

—Boris Kachka

The Five Best First Sentences

1 ‘Windows on the World,’ by Frederic Beigbeder: “You know how it ends: Everybody dies.”

2 ‘The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil,’ by George Saunders: “It’s one thing to live in a small country, but the country of Inner Horner was so small only one Inner Hornerite at a time could fit inside, and the other six Inner Hornerites had to wait their turns to live in their own country while standing very timidly in the surrounding country of Outer Horner.”

3 ‘The Truth About Diamonds,’ by Nicole Richie: “I know some people out there are thinking, Why is this girl writing a book?”

4 ‘The Diviners,’ by Rick Moody (following a portentous foreword titled “Opening Credits and Theme Music”): “Rosa Elisabetta Meandro, in insubstantial light, entrails in flames.”

5 ‘The Almond: The Sexual Awakening of a Muslim Woman,’ by Nedjma: “I, Badra bent Salah ben Hassan el-Fergani, born in Imchouk under the sign of Scorpio, shoe size thirty-eight, and soon to reach my fiftieth year, make the following declaration: I don’t give a damn that Black women have delectable cunts and offer total obedience; that Babylonian women are the most desirable and women from Damascus the most tender to men; that Arab and Persian women are the most fertile and faithful; that Nubian women have the roundest buttocks, the softest skin, and passion that burns like a tongue of fire; that Turkish women have the coldest wombs, the most cantankerous temperament, the most rancorous heart, and the most radiant acumen; and that Egyptian women are soft-spoken, offer kind-hearted friendship, and are fickle in their constancy.”

The Year of Historical Fiction

Literature is dead, but genre fiction survives, and in 2005, one particular branch emerged from the pack. Of the five books nominated for the National Book Award for fiction, the most prestigious of the annual awards, four were historical novels. The fifth was set in the eighties—by the standards of television also a historical period.Why would this happen now, of all times, when the present is so thick with occurrence? Maybe American writing has gone into retreat, accepting its role in what George Steiner once called a “museum culture”—one that accumulates the treasures of the past, sifting and weighing and measuring them, while producing nothing on its own. Certainly this would account for the strain of nostalgia that runs through some of these novels: They really wrote books, these books say, in Greenwich Village (Rene Steinke’s Holy Skirts) and on the Lower East Side (Nicole Krauss’s History of Love).

But America itself is not currently in retreat. Across the world in 2005, you could hardly go outside without being strafed by an American Black Hawk.

No, the efflorescence of historical fiction is an imperial phenomenon. It is the extension of one’s dominion in time as well as space. E. L. Doctorow has always written historical fiction, but his The March appears in a new context: We can now imagine General Sherman, like an Iraqi villager, just minding his own business, when along comes Doctorow in a gleaming new F-16 and just blows his little house down. How depressed one has to be to resurrect Carthage, Flaubert said after resurrecting Carthage during the Second Empire; but also how hungry, how greedy, how large.

The past, too, will prove not inexhaustible. What will be left for 2006, when we have established bases throughout all the Asian republics and extracted all the oil and written novels about all the major and minor figures of the past, especially in Greenwich Village? The historical novel will have to seek a more recent time frame and a narrower canvas. It will have to become memoir. Just as there was a second Gulf War, so there will be a second coming of the memoirs; some people will have to write more than one.

—Keith Gessen

The Industry Award

Ann Godoff, Penguin Press

Most denizens of the besieged publishing industry felt awfully sorry for Ann Godoff when she was fired from Random House in 2003 for failing to meet the behemoth’s new bottom line. But the veteran editor quickly parlayed her impressive list of authors into a new largely nonfiction imprint at Penguin, called the Penguin Press—taking dozens of writers with her and signing others on in short order. In her heady first year—2004—five books became best sellers, including Ron Chernow’s stocking-buster Alexander Hamilton and Steve Coll’s CIA history Ghost Wars, which won the Pulitzer. This year’s list made those accomplishments seem almost quaint: Sean Wilsey, Jeffrey Sachs, and John Berendt won the house equal parts prestige and profits. And out of the paltry fiction list—one or two a season—came Zadie Smith’s major literary comeback, On Beauty. These days, the imprint is one of Penguin’s more profitable. In other words, her bottom line is doing just fine, thanks.

— B.K.