Ever since the seventies, when ballet companies across America realized they had to grow up and operate in a more businesslike fashion if they hoped to survive, the search has been on for a spring Nutcracker. Income from the holiday perennial keeps many companies afloat, but alas, there’s only one Christmas per calendar year. How about … Cinderella! Or Sleeping Beauty! Or anything at all with a castle and a lot of dry ice! But no fairy-tale ballet has yet emerged with precisely the combination of delight, substance, and magic that will guarantee an overflowing box office season after season. Maybe it can’t happen outside the charmed environs of Christmas. Or maybe it’s that until now, nobody put Christopher Wheeldon and John Lithgow on the case.

Wheeldon, the New York City Ballet’s resident choreographer, first worked with Lithgow on the Broadway musical Sweet Smell of Success and discovered at that time that the actor had another life as the author of children’s books. Together they developed a story line for Wheeldon’s idea: a ballet set to Saint-Saëns’s The Carnival of the Animals, centering on a little boy who gets locked overnight in the American Museum of Natural History. Premiered earlier this month at the company’s spring gala, Carnival features a narrative written and recited by the ever-amazing Lithgow, who at one point steps right into the action and dances a featured role. The entire ballet is a gem, including Jon Morrell’s just-a-hint scenery and hilarious costumes, but it’s the poem that gives this production its shot at immortality. In brisk rhythms that recall Hilaire Belloc, whose Cautionary Tales ruefully describe the fate that befalls various hapless children, Lithgow conjures a world both familiar and fantastic and invites us to wander it goggle-eyed with his small hero, Oliver.

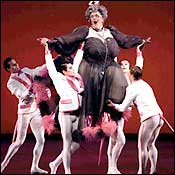

Like The Nutcracker, the ballet is about a child’s dream; but Carnival takes this motif in welcome new directions. Here the dreamer is a boy (played with great distinction by P. J. Verhoest from the School of American Ballet), and he lives not in some vaguely Germanic fairyland but right on the Upper West Side. The creatures who pop out at him during his night in the museum are strangely similar to people he knows, including his elephantlike school nurse (Lithgow’s tour de force); that old baboon, his piano teacher; and a particularly irritating swarm of rodents—“A species that always drove Oliver bats: / The Greater New York Younger Sibling.” The museum’s dinosaurs make a fine appearance as a bunch of old bones clacking away in an ancient, boring ballet, to which Oliver and his schoolmates were once dragged. And while he’s gazing at a cluster of movie-star tropical fish, we look up and spy the blue whale—exactly as hordes of city kids stare up at it in wonder every day.

Wheeldon’s choreography for these splendid beasts is smart and winning, and it’s complex enough to bear repeated viewings. He’s also woven into the mix a plainspoken, mournful duet for Oliver’s worried parents (Kyra Nichols and James Fayette, to the Cuckoo music) and a memory-laden solo for Great Aunt Cecile, who used to be a ballerina (Christine Redpath, to the Swan music). What’s missing are the passages of pure, sustained dancing that over the years have secured the Nutcracker’s identity as a ballet rather than a novelty—the snow scene, the Waltz of the Flowers, the grand pas de deux. We’ll learn in time whether the wit, the expertise, and the pleasure packed into every moment of Carnival are enough to ensure its long-term status as something more than a confection. Certainly for New York kids, many of whom grow up sprinting through the Museum of Natural History as if it’s a rainy-day playground, Carnival should be a keeper. And let’s hope this isn’t the last collaboration between Wheeldon and Lithgow. If they’re contemplating another children’s ballet set in a West Side landmark, they should definitely check out Harry’s Shoes.

Peter Martins has said that when he set out to choreograph a ballet to John Adams’s Guide to Strange Places, the composer had just one bit of advice: “Peter, this is a very strange piece. Don’t be afraid to be strange.” Sure enough, there is a wonderfully spooky quality to Martins’s new ballet, which made its debut the night after the spring gala. Looming over the stage is an ominous sky created by Julius Lumsden that changes color as the music does, and the dancers emerge mysteriously from dark, smoky recesses at the back of the stage. As for the music, a 2001 orchestral work that was receiving its New York premiere, it’s rampant with tension and the unsettling suggestion that murky forces are operating in stealth all around us. Thumps, groans, and shivers break out; we might be in a haunted house, or under the sea, or lost in our own instinctive fears.

Guide to Strange Places is the eighth work Martins has choreographed to Adams’s compositions, and it’s easy to see the allure. Adams demonstrates in this piece a gift for all the wildly askew imaginings that Martins so often seems to be heading for when he creates dances to contemporary music. But Martins just doesn’t have the vocabulary or perhaps the artistic reach to evoke such imagery as dramatically as Adams does. The dancing seems to prance atop the music, where the real depths lie.

Most of the choreography here remains safely within Martins’s familiar mode: a torrent of relentless, convoluted interactions for five highly expert couples. In one peculiar duet, Jock Soto helps Darci Kistler tie her skirt up around her neck, the better to engage in an arduous ritual that makes Soto look as though he’s partnering a giant insect. Even so, Guide to Strange Places comes off better than many of Martins’s ballets, thanks to the compelling look of the stage, the genuinely gripping music, and a barrage of terrific dancing by all.

Classical Music Listings

• Highlights

• Classical Music

• Opera

• Dance

• All Listings

Carnival

Choreographed by Christopher Wheeldon for the New York City Ballet.

Guide to Strange Places

Choreographed by Peter Martins for the New York City Ballet.